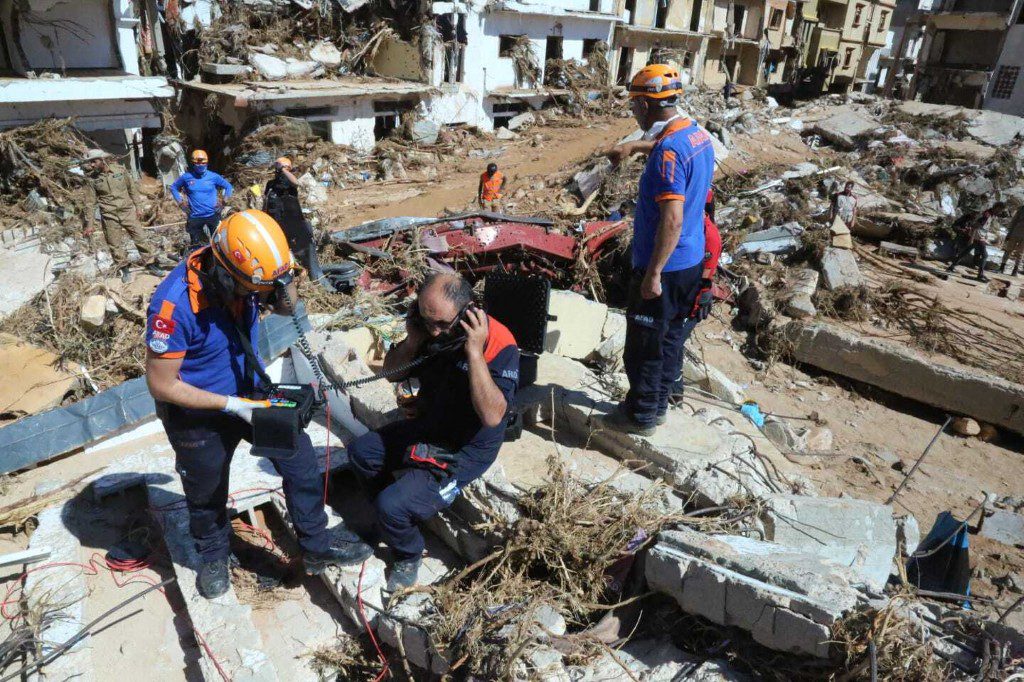

When catastrophic flooding and the collapse of two dams ripped the heart of eastern Libya’s Derna into the Mediterranean on the night of September 10, Türkiye was quick to respond. The Turkish Ministry of Defense announced that it was sending two warships to Libya carrying 360 personnel, including members of the state disaster-management agency AFAD, the Search and Rescue Association (AKUT), the Ministry of Health, Coast Guard and Fire Department. It also sent 122 vehicles, including ambulances, rescue and intervention vehicles, as well as three field hospitals, food, shelter and medical supplies.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan vowed to “ensure Libya’s wounds are healed as soon as possible.” In a remarkable move, given Ankara’s recent history in the divided North African nation, Ambassador Kenan Yilmaz visited Derna with the head of the government appointed by the House of Representatives in eastern Libya, Osama Hammad, who praised the work of Turkish rescue teams.

This outreach was a marked contrast from just three and a half years ago, when Turkish military support for western Libyan forces played a key role in turning the tide against an eastern assault on the capital Tripoli. Turkish Bayraktar drones dealt decisive blows to the ambitions of the military commander Khalifa Haftar, whose forces nevertheless continue to dominate the east today—including Derna.

To explain this seismic shift, Türkiye’s rapid aid efforts and outreach to the east must be seen through the lens of its two, long-term strategic goals in Libya. The first is preserving Turkish influence in North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean, where it is competing for oil and gas resources with its regional rivals, particularly Greece. The second is purely economic: Türkiye wants to increase its exports to Libya and boost the volume of investment between the two countries, especially in the energy and construction sectors.

Rapprochement with the East

The Derna catastrophe hit a country riven by deep political divisions. Since 2014, two authorities have been competing for power. The east and south of the country are controlled by a government appointed by the House of Representatives, but are de facto ruled by Haftar and his sons. Tripoli-based Interim Prime Minister Abdulhamid al-Dbeibah’s internationally recognized government controls the west, backed by multiple armed brigades. The UAE, Egypt, and Russia have largely supported Haftar and authorities in the east of the country, while Türkiye and, indirectly to some extent, Qatar support the western camp.

Ankara’s critical support for western Libyan forces in 2019 came with a quid pro quo: the then-Government of National Accord signed a deal demarcating the maritime borders between Türkiye and Libya, giving Türkiye rights over major undersea gas fields at the expense of Cyprus and Greece. After Dbeibah took power in 2021, he visited Ankara and reaffirmed his government’s commitment to the deal.

More recently, however, Ankara has signaled its willingness to establish closer ties with the authorities in eastern Libya. Its aid effort to Derna is a case in point, offering Türkiye a diplomatic opportunity to extend its rapprochement there. Indeed, Ankara had already taken steps in this direction well before the disaster. Recent months have seen a series of interactions between Türkiye and the eastern Libyan authorities: Aqila Saleh, the speaker of the eastern-based House of Representatives visited Türkiye in August 2022, meeting with Erdogan and Mustafa Sentop, the speaker of the Turkish parliament. Ambassador Yilmaz also attended the inauguration of Benghazi’s Mayor, Saqr Bojwari, and the Libyan-Turkish Business Council organized a trade fair in Benghazi for the first time since the country’s revolution in 2011, attracting 38 Turkish companies and 64 Turkish executives from various sectors.

It is also notable that these developments come as Türkiye mends ties with its most prominent regional competitors, namely Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. The Libyan issue has consistently been at the heart of discussions in Türkiye’s reconciliation talks with these countries. Ankara has adopted a broader regional policy of bridge-building, driven by economic imperatives, a reduction of the United States’ footprint in the region, and the stalemate in regional conflicts following the Arab Spring.

The progress of these reconciliation efforts may motivate Türkiye and eastern Libyan authorities to maintain their collaboration, especially in light of Türkiye’s economic interests. Despite the involvement of a now-defunct Turkish company in the failure to maintain the dams upstream of Derna, there is a reasonable possibility that Turkish companies will play a major role in the rebuilding of damaged cities in eastern Libya.

For its part, Ankara realizes that any effort to engage with the authorities in eastern Libya must take into consideration the interests of neighboring Egypt. Cairo is committed to preserving its influence in eastern Libya due to concerns related to its own national security and economic ventures. Moreover, Egypt continues to demand the withdrawal of Turkish military forces and their Syrian mercenaries from Libya. On the counter side, Cairo is aware that any extension of its influence in western Libya would require approval from Ankara, which is unlikely in the foreseeable future, leaving both sides at a standstill.

Russia is also a key player in Libya, supporting multiple local actors including Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, the son of ousted dictator Moammar Gaddafi. It also continues to back Haftar, who met President Vladimir Putin during a visit to Moscow in late September.

Haftar relies heavily on the Wagner Group, through which Russia exerts control over significant portions of eastern and southern Libya, including strategic oil facilities and border regions with neighboring African countries. Repeated visits by Russian Deputy Defense Minister Yunus-bek Yevkurov to Libya indicate Moscow’s determination to maintain the ongoing presence of Wagner forces in Libya and across Africa, particularly in the aftermath of the death of former commander Yevgeny Prigozhin.

Nonetheless, Ankara’s engagement with authorities in eastern Libya is likely to advance, along with the strategic alliance between Türkiye and authorities in western Libya. Full normalization in the near term is improbable, mainly due to the deep mutual distrust between Ankara and Haftar. However, steps towards reconciliation could enhance Türkiye’s ability to extend its influence throughout Libya, especially given the positive reception of Turkish relief efforts by eastern Libyan authorities and the potential for Turkish involvement in the reconstruction of Derna and other affected cities. Türikye’s formidable construction sector gives it an advantage that many regional countries involved in the Libyan crisis do not possess. If Ankara continues mending ties with both Cairo and Abu Dhabi, this may even help push Libya’s leaders to overcome the country’s long-standing political deadlock.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Middle East Council on Global Affairs.