U.S. users briefly lost access to popular social media platform TikTok earlier this week, following a legislative push to force the app’s Chinese-owned parent company to divest from its U.S. operations. While Donald Trump had endorsed the effort to ban the app during his first term, he recently reversed his stance, signing an executive order delaying the ban’s enforcement for 75 days.

TikTok has also faced criticism for alleged bias towards pro-Palestinian content during Israel’s 15-month long war on Gaza. In this interview with Afkār, Marc Owen Jones examines the motivations behind the ban and whose interests are likely to be prioritized in the evolving social media landscape during Trump’s second term in office.

Afkār: To what extent was the argument to ban TikTok on a national security basis a pretext to curb freedom of speech about the war on Gaza, particularly in relation to pro-Palestinian content on the platform?

Marc Owen Jones: The national security argument for banning TikTok reflects multiple overlapping motivations, with pro-Palestinian content being one of roughly six key factors. While there are genuine security concerns of data extraction, which are not unique to Chinese platforms, the ban also serves as a shakedown to enrich U.S. partners, an attempt to gain insight into TikTok’s algorithm, a response to moral panic over Chinese influence on youth, and an expression of right-leaning fears over losing influence over young people. However, the pro-Palestinian content factor cannot be divorced from these other motivations—it is part of a broader pattern of controlling narrative spaces under the pretext of national security. We must not forget that former Secretary of State Anthony Blinken mentioned at the McCain Institute that TikTok had allowed the U.S. and Israel to lose control of the narrative on Gaza, implying that they had control over U.S.-based platforms.

ā: If the American government acquires a half stake in TikTok’s U.S. business, how might this impact the platform’s approach to freedom of speech and content regulation on Palestine and other heavily politicized issues?

MOJ: TikTok would rather have some of the market than none at all. Undoubtedly any potential U.S. ownership would come with caveats in which national security would be used as a pretext to moderate pro-Palestinian content—and other content seen as opposed to U.S. interests. After all, Meta was found to have been censoring pro-Palestinian voices, and Google permits pro-Israel propaganda.

In the narratives surrounding social media platforms, Chinese apps are portrayed as menacing threats to national security that will “make you communist,” while American apps are framed as tools of free speech that will bring democracy. This binary framing also applies in some ways to freedom of speech and censorship, which can be construed as two sides of the same coin. The right wing’s current perspective on freedom of speech is actually a coded call for digital violence against minorities—especially Muslims. It is more likely that speech that the government disagrees with, such as pro-Palestinian speech, may be swept under anti-terror legislation. Let’s be clear—this is about freedom of speech for white nationalists.

ā: How are social media companies posturing as Trump takes office, and what are the implications of this for the parameters of public discourse within the MENA region?

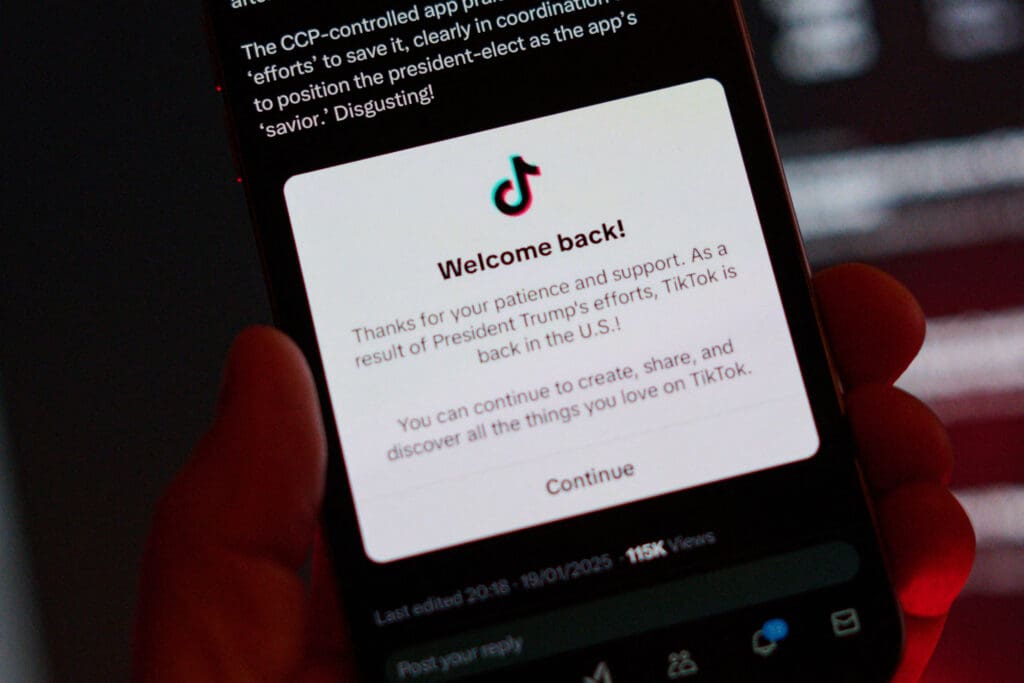

MOJ: The TikTok ban has actually paved the way for justifying bans of social media apps based on notions of national security. If the United Kingdom wanted to do this with X, it would have a strong case too. Platforms are clearly positioning themselves in anticipation of shifting political winds—just look at how TikTok is already deferential to Trump in its communications. This has serious implications for how discourse in the MENA region will be shaped and controlled.

Looking at how TikTok is already behaving—mentioning Trump in obsequious terms even in its ban notification messages—suggests how U.S. ownership would impact content regulation. Zuckerberg bending the knee to Trump, abandoning fact checking and replacing it with a poor substitute (community notes), is alarming. Let’s not forget some of these content moderation and fact checking strategies were brought in to help prevent genocide and hate speech. With so many bad actors promoting hate speech in the Middle East, and little to no regulatory frameworks, I think we will see a resurgence in platform manipulation and propaganda over the next four years.