Iraq’s new government is hoping that an influx of investment from its Gulf neighbors can breathe life into its economy and diversify its regional relationships after years of being so close to Iran. But such efforts are likely to face stiff opposition from Tehran and its proxies, who have expanded and consolidated their influence since Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani came to office in October. Al-Sudani is backed by pro-Iran factions who have long rejected moves to extract Iraq from Iran’s orbit or improve ties with the Gulf Arab states and their Western allies. Reported Saudi plans to pump billions of dollars into Iraq’s economy, if they materialize, would be a milestone both for the economy and for Baghdad’s relations with the region’s top Sunni power. But the geopolitical context and the difficulty of mustering support from his own camp mean al-Sudani will likely struggle to warm ties with the Arab Gulf states.

A History of Mistrust

Iraq’s relations with the Arab Gulf states have been strained since the 2003 American-led invasion of the country. The removal of the Baath regime lifted the lid on decades of festering sectarian tensions and corresponding regional rivalries. Iraq disintegrated into years of bloody proxy conflict that dragged in key regional powers, including Iran, who seized the opportunity to hegemonize the politics of its erstwhile antagonistic neighbor. King Abdullah II of Jordan’s comment in 2004 that a Shiite “crescent” could emerge, linking Damascus to Tehran via Baghdad, seemed to become a self-fulfilling prophecy in the following years. Ahead of the 2005 election, the leading clergyman of the Shiite world, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, mobilized Iraq’s divided Shiite political class, which paved the way for pro-Iran politicians to take control in Baghdad. At the same time, a proliferation of Shiite militias was matched by the emergence of powerful Sunni insurgents, who received arms, financial resources, and safe passage through Syria and Jordan. This context underpinned both the 2006–2007 sectarian conflict that ensued and the later horrors of the rise of the Islamic State group in Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

Despite the stakes, Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) capitals consistently failed to formulate a cogent, long-term, and strategic Iraq policy that would put relations on a better track. The country’s 2010 parliamentary elections made this painfully clear. In the run-up to the polls, there were signs a GCC-aligned bloc would emerge, led by then-Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and the chief of the Anbar Awakening Front, Ahmed Abu Risha. Saudi Arabia, which opposed al-Maliki’s inclusion, torpedoed the alliance. In some respects, Saudi apprehensions were justified in the aftermath of this limited window of opportunity. Indeed, it was during al-Maliki’s rule that relations between Iraq and the Gulf reached their nadir. In Iraq—outside the Shiite Islamist community—and in the wider region, al-Maliki was widely perceived as authoritarian, sectarian, and responsible for repressing Arab Sunnis, which ultimately helped nurture the rise of the Islamic State. Al-Maliki’s failure to build bridges with other Arab states also exacerbated the rivalries fanned by the Arab Spring. As protests swept the Arab world in 2011, prominent Iraqi political and religious figures, including al-Sistani, criticized crackdowns against Shiite protestors in some Gulf countries, much to Saudi and Bahraini irritation. In effect, Iraq became part of an Iran-led bloc, along with Lebanon’s Hezbollah, embroiled in a region-wide struggle against the United States and its Gulf allies.

The rapid ISIS takeover of northern Iraq and eastern Syria in 2014, the uprising in Syria, and the Western coalition fightback underlined the regional nature of Iraq’s woes. Both Shiite and Sunni Iraqis were by that stage fighting on opposing sides of the war in Syria, and the Islamic State’s offensive, at least initially, was welcomed by entire Arab Sunni communities in the north.

Eyes on the Home Front

Arab Gulf ties with Iraq are still undermined by mistrust, despite the best efforts of al-Sudani’s predecessor, Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi. Al-Kadhimi was able to draw on his tenure as head of the intelligence services during the war against ISIS, and attendant personal ties to regional and Western leaders, to launch a respectable attempt at improving Iraq-GCC relations. According to interviews with Saudi and Jordanian officials, al-Kadhimi, a Shiite and long-time member of the Iraqi Shiite opposition during Saddam Hussein’s rule, was perceived as being a true Iraqi nationalist without sectarian baggage. Al-Sudani, a former Dawa Party stalwart himself, by contrast, relies on the powerful pro-Iran Coordination Framework alliance and the Dawa Party, which are dominated by hardline Shiite Islamists, and whose ideological underpinning has taken on an increasingly sectarian color. Al-Sudani’s room for maneuver will therefore depend heavily on his ability to contain hardliners within Dawa and the sectarian impulses of al-Maliki himself, not to mention pro-Iran militias.

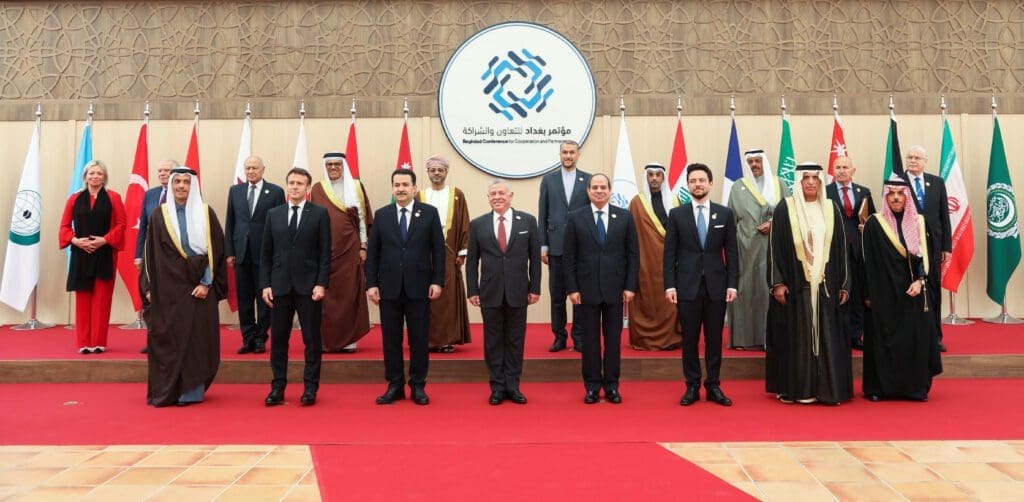

An indication of GCC feelings toward the new prime minister can be gleaned from differing attendance at the Baghdad Summits held during al-Kadhimi’s tenure in August 2021 and the one held in December 2022 under al-Sudani. The initial summit was attended by the president of Egypt, the emir of Qatar, the prime minister of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and the foreign ministers of Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia. According to sources in Baghdad, there were meetings between Saudi and Iranian representatives as an extension of the peace talks that were mediated by Kadhimi, as well as between Dubai’s ruler Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum and Iran’s foreign minister. The second summit in Amman, however, was a lackluster affair. Despite an Iranian claim that Saudi and Iranain representatives met for “friendly conversation” on the sidelines with agreement to hold future bilateral talks, other reports suggest that a substantive private conversation never occurred. The UAE, for its part, was represented by the emir of Ras al-Khaimah, which was seen by some Iraqi officials as a slight against al-Sudani himself.

GCC states still have one eye on restive Shiites at home when they engage with Iraq’s Shiite politicians. And Iraq’s political discourse is still dominated by anti-GCC narratives that are propagated by the vast network of media channels under the control of Iran-aligned actors. That said, the GCC can and should engage diplomatically with Iraq’s ruling elite, develop political and economic ties, and contain Iranian influence as much as possible. Some Gulf states have managed to nurture positive relations with Iraq. Kuwait, for example, was the only Gulf state with a strong presence at the Arab League Summit in Baghdad in 2012, and hosted the Iraq reconstruction conference in 2018, following the defeat of the Islamic State. Kuwait’s warm ties with Baghdad are influenced by Saddam Hussein’s invasion of the country in 1990, but that history also underlines the high value Kuwait places on healthy relations with its bigger neighbor. Relations with Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, continue to be marred by the legacies of the post-2003 political order in Iraq and wider geopolitical dynamics, while Iraq’s relations with Qatar have been undermined by reports that wealthy Qataris funneled money to Iraqi Sunni militants and anti-government forces and the kidnapping of Qatari nationals in 2015 by Iranian proxy groups. Attempts to mend these fences have also been hobbled by the side-lining of moderate Iraqi factions by hardline, pro-Iran groups with far greater mobilization capacity.

Diplomacy through Investment

Al-Kadhimi had overseen a flurry of outreach to Saudi Arabia, including reported 2020 talks over a potential $2.2bn Saudi investment in Iraq’s planned Ratawi gas project. This could reduce Iraq’s dependence on Iranian gas imports and potentially be Riyadh’s first major investment in Iraq’s energy sector. It would also be a confidence-building milestone and a much-needed boost to Iraq-Saudi relations. Yet history shows that hopes for better ties through economic projects ultimately depend on the stability of Iraq’s political environment and Baghdad’s ability to convince Iran and its allies that the investment will not come at their expense.

Al-Sudani will face a major challenge to consensus among multiple power centers that forge their own foreign relations independently. Any major Saudi investment in Iraq will require at least a yellow light from Iran to avoid its proxies torpedoing it. Al-Sudani can argue that investment would regenerate a battered economy and also benefit Iran and its allies as they face tough United States sanctions. Such arguments could help ease Iranian concerns and dispel the zero-sum logic of the Iranian-Saudi rivalry. That said, any further fence-mending efforts will require al-Sudani to build a favorable political coalition. Given that his key backer and patron is the sectarian al-Maliki, al-Sudani may have his work cut out. Moreover, mass protests in Iran, influential Iraqi cleric’s Muqtada al-Sadr’s potential interest in undermining the government, and Gulf apprehensions toward al-Sudani could all hobble his efforts to build on al-Kadhimi’s bridge-building achievements.

Ultimately, the Gulf Arab states’ ties with Iraq are unlikely to flourish until the latter can forge its own foreign relations independently of Iran and the former develops policies that can mitigate and adapt to dynamics that will likely underscore the political landscape for decades.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Middle East Council on Global Affairs.