The Impact of BRICS on the International Order

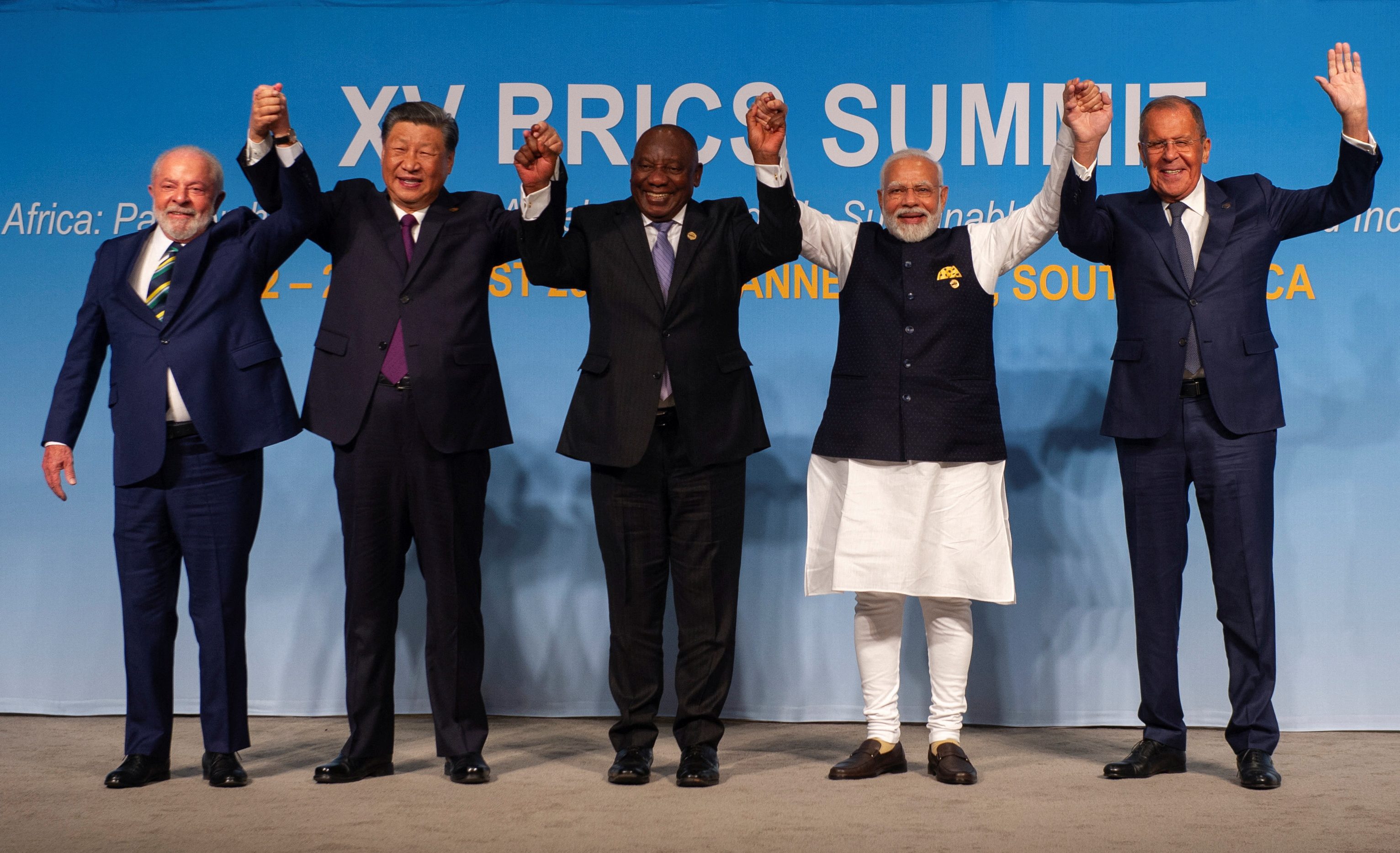

The 2023 BRICS summit has attracted unprecedented international interest due to the geopolitical context of increasing U.S.-China competition and the Global South’s balancing act regarding the Russia-Ukraine war. As competition between global powers intensifies, Western actors increasingly see this bloc, and others like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), through the lens of competition with China and Russia. They arguably regard these blocs as an institutional embodiment of resistance to the Western-centric global order.

The reform of the international system is long overdue. This system is a relic from the post-World War II era and remains unfair and unrepresentative. Plus, the current discussion in the West on the future of multilateralism fails to consider the interests and aspirations of the Global South. Against this backdrop, the expansion of BRICS possesses great symbolic importance. The bloc can give a powerful voice to the quest of reforming the global order, help crystallize and formulate the content of this reform, and showcase the Global South’s version of multilateralism. Plus, the bloc is likely to be more influential in economic sphere by advocating for a new global financial architecture, de-dolarisation of the global economy, and undermining the western sanction regimes.

However, internal fissures between members –– such as between India and China –– and diverging stances on engagement with the West may prevent the bloc from having teeth in the geopolitical realm. BRICS also risks becoming China-centric, which will dilute its power and claim of providing a voice to the Global South. Resolving tension between the interests and aspirations of the existing BRICS members was already a tall order; the decision to more than double the bloc’s size with countries spanning Argentina to Saudi Arabia will only make this more difficult.

BRICS Expansion: Gulf Prospects and Global Geopolitics

Ahead of the August summit, South Africa’s ambassador to BRICS, Anil Sooklal, declared that the bloc would initiate “a tectonic change … in the global geopolitical architecture.” Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates are among the new members invited to join in January 2024. The inclusion of these countries is a significant step towards any tectonic change in the world order and indicates the growing role of the bloc on the global stage.

For such Gulf countries, the attraction of BRICS lies in the bloc’s role in an emerging multipolar international system, with some members announcing their intentions to reduce the centrality of the U.S. dollar in global markets. Their imminent entry into BRICS signals growing ambitions to chart their own, more autonomous foreign policy and develop alternative partnerships and blocs free from Western influence. With China rising and the West a declining influence in the Gulf, it is not surprising that BRICS membership has become more attractive to counterbalance such changes.

The downside may be that current Chinese and Russian influence in BRICS is leading to a greater anti-Western tilt than ever before. Brazil, India, and South Africa, however, see the risk this creates to their foreign policy ambitions to use BRICS to increase their economic engagements, whether with the East or West. It may not be a tectonic shift, but the addition of these Gulf states to BRICS is certainly a step towards a multipolar future.

Saudi Arabia’s BRICS Membership

At the recent BRICS summit, Saudi Arabia was invited to join the group as a new member, along with five other states: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates. The expansion of BRICS comes amid intensifying rivalry between United States and China, as well as the deteriorating Saudi-U.S. relationship under President Joseph R. Biden and Riyadh’s pivot to China.

While Saudi Arabia is yet to approve its membership, doing so would serve the country’s short-term economic and political ambitions. Ensuring regional stability is a top priority for Saudi Arabia, as this would foster the attractive investment environment needed to meet its economic and social transformation goals outlined in its Vision 2030. While closer relations with China does not provide the security umbrella that the U.S. has long offered its Gulf partners, China’s diplomatic efforts to mediate between Saudi Arabia and Iran in April has led to considerably reduced attacks from Iranian-backed Houthi fighters from Yemen and fostered an environment of regional de-escalation that offers Saudi Arabia more security. Moreover, joining BRICS helps diversify the kingdom’s political partnerships and provides access to stronger relationships with other bloc members.

Given Riyadh’s role as the de facto leader of OPEC+, its membership in BRICS would bring the bloc’s share of the global oil supply to 42%. This will increase the kingdom’s leverage in countering any potential Western sanctions on oil producers. Already, in light of the West’s price cap on Russian oil amid the war in Ukraine, the Saudi energy minister stated that the “kingdom will not sell oil to any country that imposes a price cap.” Should Saudi Arabia become an official BRICS member, this stance would significantly undercut the efficacy of Western sanctions.

Why Does Iran Seek BRICS Membership?

In the short term, Iran sees BRICS membership as a way to circumvent international sanctions that have stunted its economy. The sanctions regime imposed by the United States following former President Donald J. Trump’s 2018 withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action has been debilitating, and Iran has looked to Asian trading partners to mitigate the impact of sanctions. This strategy has offered a reprieve. China’s strategic commitment to Iran, highlighted in the 2021 bilateral agreement as part of its Belt and Road Initiative, is an important lifeline. BRICS offers Iran an institutional framework to expand its international trade and mitigate the impact of U.S.-imposed economic isolation.

Suggestions by Russia that trade within BRICS could be conducted in national currencies, and the prospects of a new BRICS currency, promise significant advantages to Tehran. As BRICS looks over the horizon for growth, its New Development Bank will gain greater significance for countries like Iran that are desperate for the injection of new funds.

In the long term, with China and Russia as major players, BRICS aligns well with Iran’s vision of a global counter-hegemon to resist Washington’s unilateral sanctions and domination of international fora. This is consistent with China and Russia—both of which are engaged in a protracted rivalry with the United States. While Moscow and Beijing are reluctant to be explicit about BRICS as a counterweight to the liberal financial order, they would benefit from a weakening of the United States’ hold on global finance. This alignment is seen by the authorities in Iran as the best opportunity to mount a concerted push for an alternative world order.

Egypt Joining the BRICS: Good News, But Challenges Remain

Egypt’s joining of BRICS is likely to be advantageous to the country, which is facing a severe economic crisis. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Egypt’s currency has lost more than 50% of its value and inflation reached 36% in June, putting pressure not only on Egypt’s most disadvantaged but increasingly the middle and upper classes. By joining the grouping, Egypt can increase its non-dollar dominated trade with the countries of the bloc, as well as seek funding from the BRICS Development bank as it aims to meet its steep debt obligations.

While Egypt’s admission to BRICS is good news for its economy, it is not a silver bullet that will solve all of Egypt’s economic woes, as some government supporters have been touting. Much more structural reforms will be needed to tackle Egypt’s long-term economic challenges, and BRICS is only a small piece of a much larger puzzle.

Moreover, BRICS membership poses foreign policy challenges for Egypt as it balances between traditional partnerships with the U.S. and Europe, and powerful BRICS members China and Russia, who view the bloc as a vehicle for challenging Western geopolitical and geo-economic hegemony.

Finally, Ethiopia’s inclusion in the grouping is notable, given the country’s ongoing differences with Egypt over the GERD dam. Should the BRICS want to highlight its growing global influence, a successful mediation between its two newest members would be a great start.

The BRICS Challenge to the West is Mostly Hype

There has been much fanfare surrounding BRICS and the coalition’s aspirations to challenge the Western dominated international order. Indeed, the admission of six new members—and the desire to join by many more—reflects, according to some observers, the emergence of a multipolar world order in which the United States no longer reigns supreme. However, when digging beneath the surface of BRICS to assess the fundamentals of the coalition––its objectives, cohesion, and underlying principles––the picture becomes somewhat underwhelming.

Firstly, the viability of BRICS rests predominantly on China’s capacity to maintain its economic rise and fulfil its Belt and Road vision, which has come under pressure as a result of China’s debt crisis and post-pandemic economic woes. Secondly, BRICS is underscored by hopes of establishing an alternative to the dollar as an international reserve currency. But this is aspirational at best and delusional at worst, since the dollar’s dominance is a reflection of the institutions, financial exchanges, international businesses and values that collectively underpin the international economic order, which has developed over the course of a century. Thirdly, out of the six countries invited to join the group, four—Argentina, Iran, Ethiopia, and Egypt—are in financial ruin and facing varying degrees of political instability or civil unrest. This is hardly the making of a credible coalition that can rival the G7.

BRICS will not rebalance the global international order, but it does reflect the myopia of U.S. foreign policy and frustration toward Western powers’ commitment to the Middle East. For Saudi Arabia and the UAE, membership provides geopolitical depth, resilience and bandwidth amid the uncertainties surrounding the future of U.S. engagement in their region, and the certainty of increased engagement from China.

BRICS Pay? – A First Attempt at the Reconfiguration of Payment Systems

A discussion of de-dollarization was anticipated to take place at the 14th BRICS Summit held in Johannesburg. However, the five leaders were not able to reach a consensus statement towards launching a common reserve currency, or the “R5,” a basket encompassing the Brazilian real (BRL), the Russian ruble (RUR), the Indian rupee (INR), the Chinese renminbi (CNY), and the South African rand (ZAR). From the onset, there was very little expectation for the creation of a currency union, given the diverging interests of the members.

Lesser initiatives like BRICS Pay, a digital payments platform being jointly developed by member states, clearly does not pose a significant threat to the established, dollar-based global financial system on the scale of a common currency. The important question is whether BRICS Pay will effectively function as an alternative payment system for financial transactions amongst the five countries and six new members, with the CNY playing the central role.

Given Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s addition to BRICS, the two petrostates may diversify their payment options––albeit incrementally––by conducting more oil transactions in CNY, using the Shanghai Petroleum and National Gas Exchange as a settlement platform. Iran, also invited to join BRICS, has been settling in CNY for trade with China while under U.S. sanctions since the functional end of the JCPOA. The UAE’s participation in the Bank of International Settlements’ Project mBridge for CBDC (central bank digital currency) interoperability indicates its growing role in the international financial system. Moreover, the finalized Project Aber between the Emirati and Saudi central banks will enable the two petrostates to maneuver in alternative payment systems.

What Is Driving Tunisia’s Interest in BRICS?

In April, a Tunisian presidential spokesman announced the country’s intention to join BRICS. Initially, Tunisia’s interest in BRICS membership was interpreted by analysts as an attempt to break free from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and secure alternative sources of financing, especially in light of the country’s economic hardships and credit crisis. While this has been the case of a number of states, notably Egypt, Tunisia has other motivations driving its interest in BRICS. Membership would allow Tunis to exert pressure on the West by capitalizing on its position as a significant node on migration routes to Europe. The country has already successfully leveraged this position to secure a migration deal with the European Union, receiving financial assistance in exchange for curbing undocumented immigration.

In fact, prospects of joining BRICS were brought up shortly after Tunisian President Kais Saied turned down a $1.9 billion IMF bailout package, on account of demands for subsidy cuts that he referred to as “diktats.” Despite Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s recent statement in support of Tunisia’s IMF talks, there has not been an official statement by the Tunisian government nor a formal application. Moreover, recent declarations by the Tunisian Minister of Economy and Planning Samir Saied negated the possibility of joining BRICS given the size of the economy and the country’s limited trade relations with BRICS members. Ultimately, the stalled IMF bailout and the desperate need to revive the economy are key factors driving Tunisia’s interest in BRICS.

BRICS and Energy Security

With the addition of six new members to BRICS, including major hydrocarbon exporters Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, the expanded bloc will control over 40% of global oil supply and over 50% of gas reserves. Even before the expansion, the bloc already represented 40% of energy consumption. China and India alone are projected to account for half of the world’s energy growth by 2035. Despite this expected growth and the fact that some of the new BRICS members are major energy producers, the countries face intricate challenges that necessitate comprehensive reforms to ensure their long-term energy security. Although Brazil and Russia enjoy relative energy independence, China and India are among the largest importers of crude oil globally.

Additionally, the expanded BRICS will control 72% of the world’s rare earth minerals like manganese, graphite, nickel, and copper. This, combined with the new members’ strategic geographic positions, technology, expertise, and wealth, will give the bloc greater control over global energy supply chains. Moreover, BRICS will be better positioned to bypass Western sanctions and stimulate investment in, for instance, Iran’s underexploited and substantial reserves of critical minerals.

The bloc could also influence its members’ energy policies and enhance their energy security. However, this influence also brings challenges, such as delaying the implementation of international environmental treaties, due to the members’ growing energy demand and easy access to fossil fuels. Furthermore, the bloc might pursue a more coordinated approach and restrict their exports of critical minerals, which would cripple the global supply chain. Careful management and a balanced approach to mineral exports, fossil fuel production and consumption, and the transition to renewable energy will be necessary to ensure the bloc’s influence leads to a more secure and sustainable global energy landscape.

Council Views is an ME Council article series that brings together our experts’ insights on headline issues facing the Middle East and North Africa region.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Middle East Council on Global Affairs.