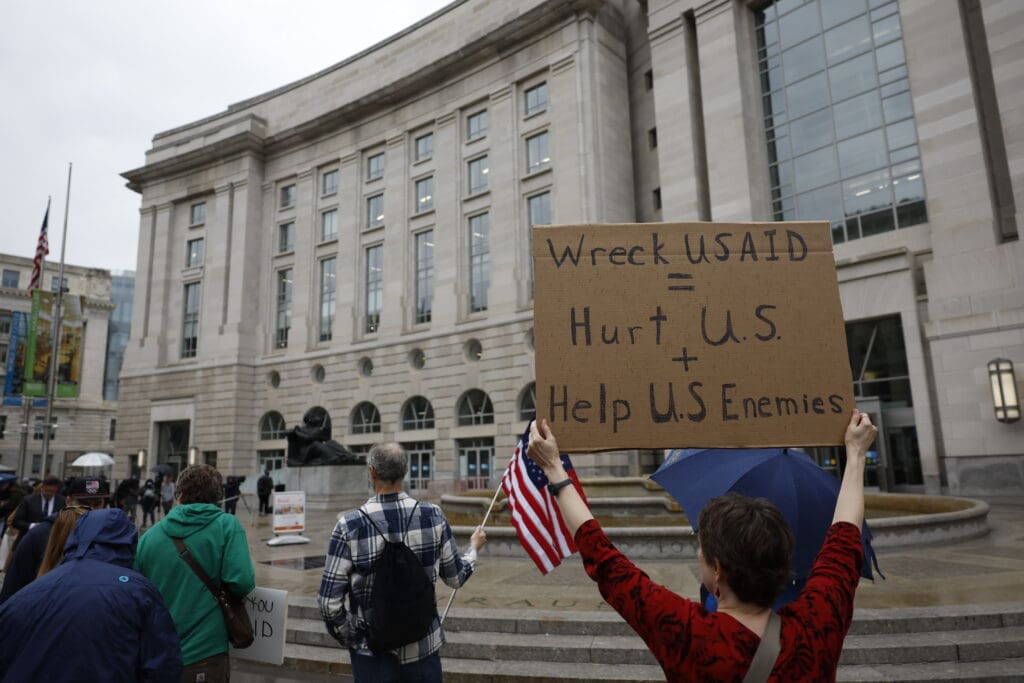

Amid the whirlwind of executive orders and major policy shifts coming out of the White House, President Donald Trump’s decision to freeze the operations of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), which administers most U.S. foreign assistance, threatens to have a wide impact around the world. If prolonged, many programs in countries across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), including those focused on economic stabilization, infrastructure development, agriculture and civil society, could face serious, adverse effects.

These cuts also come at a precarious time for U.S. relations with the Arab world. Two decades after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Arab popular opinion of the U.S. had significantly improved from levels found in 2003. By the early 2020s, Arab Barometer survey results revealed that in most countries, between 40 percent and half of citizens reported favorable attitudes toward the U.S. Yet, much of this goodwill evaporated in the 17 months since October 7, 2023. Given the role U.S. foreign assistance has in boosting the image of the country abroad, Trump’s aid cuts may compound this trend in a way that would be difficult to recover from.

After October 7, former President Joe Biden’s promise of “ironclad support” for Israel, which included supplying much of the military equipment necessary for Israel’s military campaign in Gaza, caused MENA publics to quickly turn against the U.S. In Tunisia, for example, U.S. favorability dropped by 30 points in the first 20 days following October 7. In other countries across the region, double-digit drops in U.S. favorability were common.

Moreover, the implications were not just limited to general attitudes. Arab Barometer results revealed that in most countries U.S. companies would encounter far less receptivity for being the preferred partner on infrastructure projects compared with the pre-October 7 period. In multiple countries, citizens reported that China was better than the U.S. at protecting rights and freedoms or maintaining regional security.

Final Foothold

Despite the broad shift in negative perceptions of the U.S., there was one clear exception in Arab Barometer results: U.S. foreign assistance. When asked if U.S. foreign aid helped strengthen three areas—education, women’s rights and civil society—a majority of citizens in all but one country polled perceived it as favorable. In fact, there was an increase in the perceived effectiveness of U.S. foreign aid in nearly all countries for these three areas. For example, from 2022 to 2024, there was an increase of more than 10 points on all three items in Morocco, at least five points in Mauritania, and at least four points in Jordan. Thus, despite a major drop in overall U.S. favorability, people believed that U.S. assistance was effective in certain areas of their lives.

Importantly, this perceived effectiveness was linked with a desire for closer ties with the United States. In Morocco, for example, 68 percent of respondents who said that U.S. assistance strengthens education initiatives to a great or limited extent wanted closer economic relations with the U.S., compared with 44 percent who believed U.S. aid has limited or no effect in strengthening education initiatives. A similar gap appears in Lebanon, where those who believed U.S. assistance helps education were 22 percentage points more likely to want closer economic ties with America. Elsewhere, the difference was 14 points in Iraq, 11 points in Jordan, and nine points in Mauritania.

Notably, Arab citizens were not naïve about the soft-power motivations behind American aid. More than half of respondents in Lebanon, Iraq, Tunisia, Jordan and Mauritania cited U.S. influence over their country as the primary reason for the assistance, rather than more altruistic reasons, such as a desire to promote economic development, increase internal stability, empower civil society organizations, or improve citizens’ lives. Only in Morocco was this not the case—29 percent considered gaining influence as the top reason. Nonetheless, the value placed on the aid demonstrates pragmatism and does not damage America’s reputation among recipients.

Additionally, even if U.S. assistance extends to areas that are not fully in line with the desires of citizens, it still has a positive effect on America’s image. For example, most people polled wanted aid for economic development, followed by infrastructure and education. Fewer cared about programs to promote women’s rights or civil society. Nonetheless, America’s image benefited from the aid even when it did not align perfectly with the priorities of its recipients.

These realities make freezing U.S. assistance all the more damaging for American interests in the Middle East and North Africa. At a time when U.S. favorability in the region was already very weak, continued assistance represented a clear way for the Trump administration to help counter these trends. Instead, the abrupt severing of aid is likely to further harm perceptions of the U.S. and make it more difficult to win hearts and minds. As such, a critical stalwart of American soft power is being eliminated along with the losses of key programs benefiting the people of the region.