*This article is the second part in a two-part series. Read Part 1 here.

If Syria’s Arab Spring forerunners have a fundamental lesson to impart, it is that achieving a symbiosis between a revolution’s leadership and its public is required to successfully transmute a deposed tyranny into a nation of self-determination and the representative state that all crave.

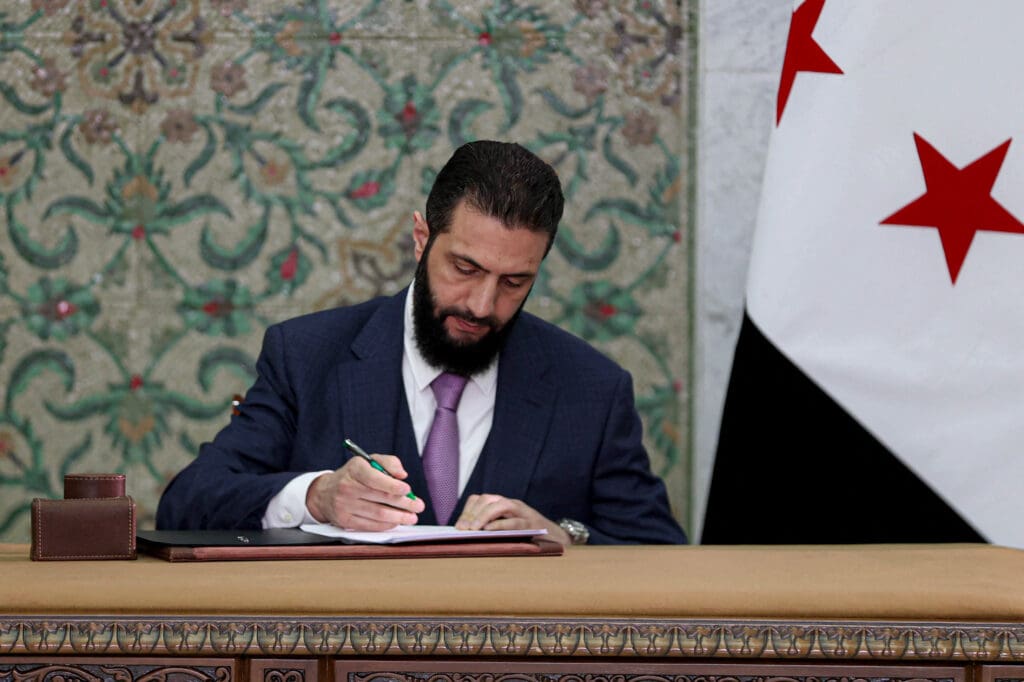

In other words, only Syrians as a collective can shape a nation that they will collectively buy into. While the grand projects that animate the state, like its bureaucracy, economic and foreign policies, are necessarily top-down endeavors, Ahmed al-Sharaa must deliver policies that empower Syrians in order to get the popular support, legitimacy, direction and engagement required to keep ruling and reshape the pillars of the state to complete the founding of the new national project.

Syria’s predecessors failed on both counts. Revolutionary leaderships fossilized into detached autocracies, allowing the legacy system to regrow around them and cut themselves off from their people. The failures that spurred that evolution were an inability to gain legitimacy through government service, ignorance of how to promote prosperity, and an inability to harness geopolitical currents or escape predatory states.

Government Means Governing

While it was the lack of political vision that churned the popular frustration and insecurity that swallowed the region’s previous revolutions, it was the failure to provide for the people that crushed these projects into such easily digestible morsels.

In Tunisia, people gave up on a democracy that neither protected, employed nor fed them. In Egypt, Mohammed Morsi could not inspire his state to serve or be civil. In Libya the state’s decay and the economy’s “mafiaization” rotted the revolution and its people and cultivated nostalgia for the tyranny that birthed all these dynamics.

Sharaa’s job is harder than that of his predecessors. Syria is a Frankenstein’s monster of all their flawed political economies. The war-time sanctions imposed on Assad, and the Libya-style mafiaization of the economy, as militias, foreign mercenaries and oligarchs—or the crude ménage à trois between them—presided over the state’s main rents (or wholly criminal enterprises like the Captagon trade), rendered Syria destitute. And like Tunisia and Egypt, Syria enters its transitional period with little money, a functioning—if bloated—bureaucracy, a skeptical deep state, and an oligarchy that dominates public sector spending and private sector activity.

Worse still, Syria lacks the finances to secure necessities, let alone begin a reconstruction estimated in the tens of billions of dollars. The first trap Tunisia fell into was being pressed by Western and Gulf allies into high-interest borrowing under the Deauville Partnership with Arab Countries in Transition, seemingly as a punishment for toppling their tyrant. To avoid debt’s self-tightening chains, Sharaa must convince Syrians that rebuilding will necessarily be a long and rocky process.

As the positive public response to his first national address demonstrates, Sharaa can buy the patience he needs if he just communicates his restrictions, logic and goals to his people. Active communication is Sharaa’s method for reforging the weapon that could kill him—popular frustration—into the shield that protects him and the entire revolutionary project—popular sympathy. It is also, perhaps, the only way to lengthen his honeymoon period.

A Syria for All Nations

Sharaa’s key to unlocking Syria’s political economy lies abroad. But while it may have seemed like much of the world celebrated Assad’s fall, Syrians will find few friends to help them get back on their feet. Amidst a crumbling global order stalked by predatory middle powers, Sharaa must manipulate the geopolitical tug-of-war over Damascus to strengthen his national interest and make Syria Syrian again.

If the Arab Spring nations’ fundamental lesson for sustaining a revolution is symbiosis, then their primary lesson on protecting the revolution is: Beware the counter-revolution.

Since 2011, the United Arab Emirates—often quietly supported by Israel—led the regional opposition to the political change that was underway during the Arab Spring uprisings. Usually advertised as countering political Islamism, this reactionary opposition also conveniently aligned with Abu Dhabi’s fears that the revolutionaries’ calls for representative politics would reach its own shores, while serving as a vehicle for “little Sparta” to reconfigure the old regional order with its own client regimes.

By leveraging political and economic ties with deep states to undermine the progress of political transitions—best seen in Morsi’s Egypt—and stirring sectarian divides by arming and funding breakaway groups, like Khalifa Haftar’s east Libyan rebellion, the counterrevolutionaries were able to reverse the tide of change.

Eventually, this attracted opportunistic support from other outside actors like Russia and Türkiye, which leveraged their hard power to make pliant proxies that could be exploited for economic or geopolitical gains. Meanwhile, Europe proved itself incapable of supporting democratic transitions and lacked the strategic or moral compass to navigate its rivals’ machinations.

Today, Syria is already being softened up. Russia allegedly spirited away senior military officers, including former army chief Maher al-Assad, for unknown purposes. Israel has expanded its occupation and seized strategic territory holding key water resources, fomented sectarian divisions by claiming to be operating in protection of religious minorities like the Druze, imposed restrictions on Syrian military deployments in a large part of the country, and lobbied the U.S. to maintain sanctions; all to keep Syria mired in the crises that cultivate unrest. To make matters worse, Iran is also purportedly engaged in its own destabilizing activity through the Alawite community.

A Way Forward Centered on Economic Development

Sharaa’s leadership path is a minefield on both foreign and domestic fronts. But he at least has examples of where not to tread.

Promisingly, Sharaa is already removing Assad-era duties on imported goods to lower prices and offer relief to the private sector. But economic growth requires engaging the Syrian oligarchs who retain the power to reignite the country’s economy. The savvy approach at this stage would be to not challenge the oligarchs’ existing lawful businesses, if they in turn do not challenge a growth in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in favor of protecting monopolies. Then, the caretaker government should reduce domestic red tape to help stimulate growth.

Marketing Syria’s rebuild as a national project is the key to securing the broad buy-in required for such a long-term, holistic endeavor, and weaving it into foreign and domestic policy. Tasking the civil service to draft the medium-term strategy for cohering the many required projects provides them with a new sense of purpose and prepares them to coordinate.

Positioning the civil service as coordinators would help Sharaa make the most of international development assistance, while crucially keeping control in Syrian hands. It would also be a vehicle for bridge-building between the state and civil society, facilitating symbiotic progress and helping sell this as a national project.

International development organizations and Western foreign policy systems are invaluable wells of experienced help to initiate urgent projects, train Syrian civil society and restore capacity in key areas like agriculture. Building ministry-to-ministry relationships with Europe, which remains systemically geared towards values-based assistance, also helps stabilize the new relationship. Synergizing the national project with European goals, like green development, can also savvily help fast-track major projects like recreating Syrian energy infrastructure.

Similarly, restoring former trade with Türkiye should be prioritized, surging capital flows, catalyzing economic rejuvenation and stimulating growth that incentivizes further Turkish support. Sharaa should continue that model with other regional powerhouses like Saudi Arabia, incentivizing powers to create mutually beneficial equities in Syria. This could dilute the influence of the counter-revolutionary states without confronting them, while recruiting allies for sanctions relief and other international lobbying.

Sharaa’s test will be his ability to successfully balance these partnerships and prevent each from souring others or blowing up in his face. For example, while an economic relationship with Türkiye is vital, security dependency risks undermining national sovereignty—as happened in Libya—a particularly perilous hazard given the growing bond between Ankara and Abu Dhabi. Sharaa must also diplomatically sidestep what will be increasingly forceful Turkish attempts for an agreement on maritime boundaries, given it would inflame relations with Europe and unnecessarily drag Syria into the eastern Mediterranean spat over economic zones.

Similarly, Sharaa must try to fuse ministry-to-ministry relationships with Europe, while sidestepping the European culture war issues, like Russia, Türkiye or migration, which are dominating and degrading European politics.

Ironically, Syria’s refugees in both Türkiye and Europe may well be Sharaa’s greatest conduit to securing developmental support, and potentially even cultivating unique private sector ties by encouraging Syrian entrepreneurs abroad to open regional offices back home. However, this may be far too volatile a piece of diplomatic alchemy to attempt at this sensitive stage.

Ultimately, the fate of the transition returns to the issue of symbiosis. If Sharaa wants to make Syria’s revolution sustainable, let alone successful, he must empower Syria’s civil service and civil society to shape and own a national rebuilding project. This would extend his honeymoon and reduce footholds for the counterrevolution. Then, he must simultaneously develop new, mutually beneficial relationships with all involved, attracting the wide range of players and investments Syria needs. This would help create multiple joint dependencies to defend him against the counterrevolution and avoid being forced into geopolitically destabilizing positions to protect a single relationship he may need.

The Arab Spring has taught Syria and Sharaa that both their ambitions live and die together. The rest of the region, which needs them to succeed, can only hope that they have learned.