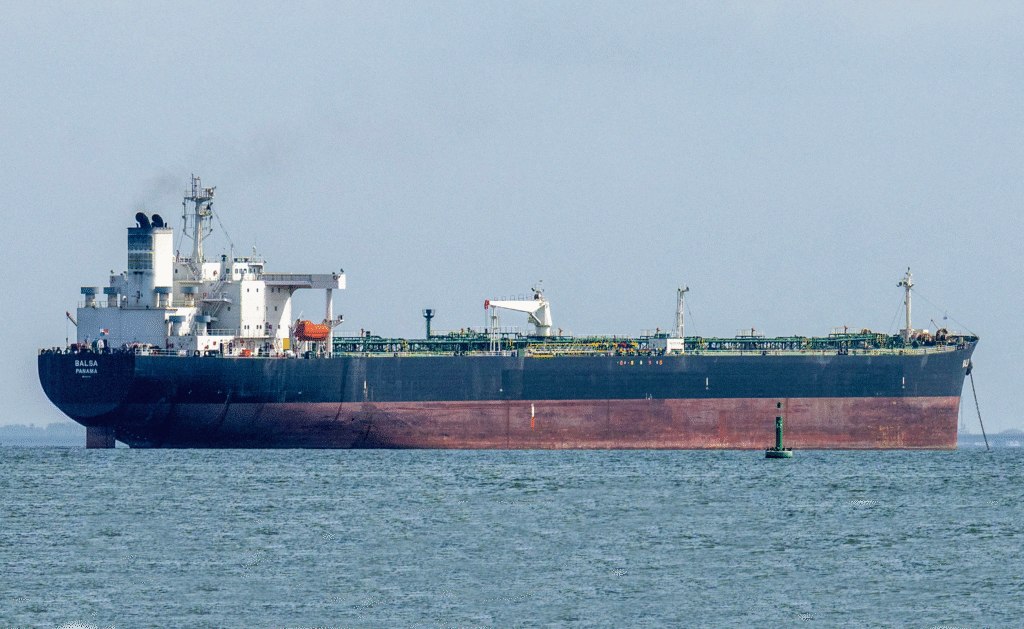

One month after the Trump administration’s abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, the contours of a new oil order are beginning to emerge. U.S. authorities continue to seize “shadow fleet” oil tankers—at least seven, so far—carrying sanctioned Venezuelan exports in a pressure campaign that began in the run-up to Operation Absolute Resolve. President Donald Trump has meanwhile declared that roughly 50 million barrels of Venezuelan crude have been taken to the United States for processing and sale, with the proceeds collected and redispersed by the administration. Trump has also called on private investors—above all, U.S. oil companies—to mobilize as much as $100bn to revamp Venezuela’s oil sector in as few as 18 months. While the rhetoric has been ambitious, on-the-ground challenges are also substantial. Risk-averse private capital has yet to move in force, as sanctions removal is taking time, and political and legal uncertainty persists. For now, Venezuela’s oil industry remains in a “wait and see” situation.

Amid the noise and confusion around Venezuela, a deeper question has emerged. With the United States already the world’s largest oil producer, what does Washington’s move in Venezuela actually achieve—and what are its implications for global oil markets, particularly for producers in the Middle East?

At first glance, the United States’ re-emergence as the anchor of a Western Hemisphere–centered oil system may be deeply unsettling for Arab Gulf producers. With Washington now exerting direct or indirect leverage over oil output stretching from Canada to Guyana and Venezuela, encompassing nearly 20 percent of global oil supply on a gross basis, the balance of power in global energy markets could start tilting westward.

If so, would it undermine the ability of Gulf producers to manage markets, influence prices, or retain strategic leverage? The answer is very much nuanced.

What Washington has gained in Venezuela is not centralized control over global oil flows, but strategic insulation from price shocks and future geopolitical risks, at a moment of intensifying great-power competition and chronic market volatility.

Still, U.S. power in oil markets remains diffuse, commercial, and politically fragmented. Production decisions are made by hundreds of private firms constrained by capital discipline, market fluctuations, regulatory uncertainty, shareholder scrutiny, and electoral politics. Even when Washington exerts influence, as is the case in Venezuela, it is doing so through providing access to private oil companies, licensing and regulatory tools, and financial channels, rather than through the kind of coordinated production discipline that defines, by contrast, the Opec+ alliance. This distinction matters.

The U.S. still lacks the single most important lever in moments of oil market stress: coordinated, deployable spare capacity. Despite its robustness, U.S. shale production is responsive to price signals, but it cannot be surged at will, shut in for strategic reasons, or sustained at a loss to achieve geopolitical objectives. Those capabilities remain overwhelmingly concentrated in the Arab Gulf—above all in Saudi Arabia and then the United Arab Emirates.

The emerging oil order is therefore best understood not as a zero-sum contest between the United States and the Gulf, but as bifurcated control of the marketplace.

The United States is increasingly positioned to control the ceiling of the market—limiting how high prices can rise. Domestic abundance, combined with expanding hemispheric influence, allows Washington to counter price spikes that carry acute political costs in a system highly sensitive to inflation between electoral cycles. Control over Venezuelan exports enhances this capacity, not necessarily by manipulating its own production flows, but by signaling the potential release of additional supply from Venezuela and, eventually, from neighboring Guyana, as its capacity continues to grow. Historically, this function formed part of the tacit bargain between Washington and Riyadh, often coordinated to try to limit inflationary pressures or cushion slowdowns in the global economy. Washington will also have access to, reportedly, one of the world’s largest crude reserves, at a time when outlooks suggest demand for hydrocarbons is growing for another two decades, at least.

Gulf producers, by contrast, will continue to shape the floor of the market, preventing prices from collapsing through deliberate supply management. After all, price crashes are as hurtful and potentially destabilizing as price spikes. Spare capacity, coordinated restraint and the ability to remove barrels from the market quickly remain powerful tools that only Opec+—and particularly its Arab Gulf core of Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Kuwait, alongside Iraq, Russia and Kazakhstan—can deploy at scale. In a fragmented geo-economic landscape, Opec+ thus remains the system’s essential stabilizer. To put things in perspective, the role Opec+ played in managing markets and preventing the global economy from a hard landing during the pandemic, remains the group’s most powerful asset.

Opacity no more

For more than a decade, global oil markets have operated under a dual structure. One market was visible and regulated, defined by Brent and WTI benchmarks, Opec+ quotas, and official supply balances. Alongside it operated a shadow market shaped by sanctions and geopolitical bargaining, where oil functioned not only as the most vital commodity for the global economy, but a currency of regime survival, traded at steep discounts among a narrow circle of states willing to defy or circumvent Western pressure aimed at isolating them.

Among consumers, China was the principal beneficiary of this parallel order. By purchasing sanctioned crude from Venezuela, Iran and later Russia, Beijing secured highly discounted energy—a comparative advantage over its great-power rival—insulated parts of its economy from global price swings, and expanded its geopolitical reach by providing financing, diplomatic cover and long-term political alignment. For Gulf producers, this shadow trade was an uncomfortable but unavoidable feature of the market, especially given China’s central role in their own demand growth.

But that permissiveness is now fading. As Washington intensifies pressure on Beijing, Venezuela has become a test case for a broader doctrine—one aimed at forcibly reintegrating sanctioned oil into U.S.-controlled or U.S.-aligned channels.

If sustained, this approach narrows China’s room for maneuver. Venezuelan crude, once sold at deep discounts, would increasingly be marketed under U.S. oversight and priced close to global benchmarks. Iranian oil remains accessible for now, but its future availability depends less on market dynamics than on political calculations in Washington. The Trump administration appears to favor regime decapitation and behavioral coercion rather than wholesale political dismantling, a lesson drawn from earlier military interventions. Should pressure on Tehran intensify, China’s access to Iranian barrels could also become less certain.

Russian crude is already constrained by sanctions following Moscow’s military invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Even if the Trump administration’s efforts to broker a ceasefire and political arrangement in Ukraine fail and sanctions relief for Russia does not materialize, dynamics would still shift. The reintegration of Venezuelan—and potentially Iranian—crude at market prices would reduce the competitive pressure that has sustained large price concessions on Russian oil. In other words, Russia would no longer need to significantly lower its oil prices to compete in the parallel marketplace. Discounts would narrow, even if formal sanctions remained in place.

Taken together, these pressures do not eliminate sanctioned oil flows overnight, but they compress the discounts that made them strategically valuable in the first place. The era in which China could reliably benefit from structurally cheap, politically insulated energy supplies is therefore coming under strain. In this context, the Gulf producers—long viewed in Beijing as one option among many—regain relative importance, not because their barrels are cheaper, but because they are reliable, scalable and politically legible.

For Opec+, the erosion of the shadow market addresses one of its most persistent challenges: opacity. With sanctioned oil no longer undercutting official supply as aggressively, the group may find greater room to maneuver, provided it can manage the reintegration of constrained producers without destabilizing prices. But Washington’s actions also raise important questions about Opec+’s future composition, including whether Venezuela remains within Opec over the medium term and whether political change in Iran could prompt a reassessment of its membership in the medium- to long-term.

If U.S.-based international oil companies (IOCs) re-enter Venezuela at the scale now being discussed, Caracas may be compelled to accommodate the commercial and policy preferences that accompany such capital. In practice, the terms may be set more by the firms—and the U.S. government—behind the investment than by Venezuela’s government.

More broadly, Opec’s focus—directed by its de facto leader, Saudi Arabia—is increasingly oriented toward the next two to three decades. Its producers believe global oil demand will continue growing over that horizon, and are investing accordingly to expand capacity and market share. By contrast, large parts of the Western oil industry are grappling with capital discipline, resource depletion and an increasingly unfavorable investment environment shaped more by climate politics than energy security.

None of this implies a clean, imminent or permanent reordering of the global oil system. The durability of this emerging arrangement depends on sustained political will in Washington, which remains vulnerable to electoral cycles, partisan politics, institutional fragmentation and the limits of enforcement over time. Meanwhile, shadow markets rarely disappear entirely. They adapt, re-route and reprice as political alignments shift and geopolitical pressures fluctuate. But even partial shifts in oil markets reshape behavior across producers and consumers alike. In that sense, Venezuela matters less for the control it offers than for the precedent it sets, in a world where power and competition are once again shaping order.