Turkish Foreign Policy in an Unhinged World

Issue Brief, May 2024

Key Takeaways

Persistence of Türkiye’s Quest for Autonomy and Status: Economic concerns are set to play an increasing role in Türkiye’s foreign policy. Despite this, Ankara’s quest for autonomy in its foreign policy and status in international affairs is set to continue.

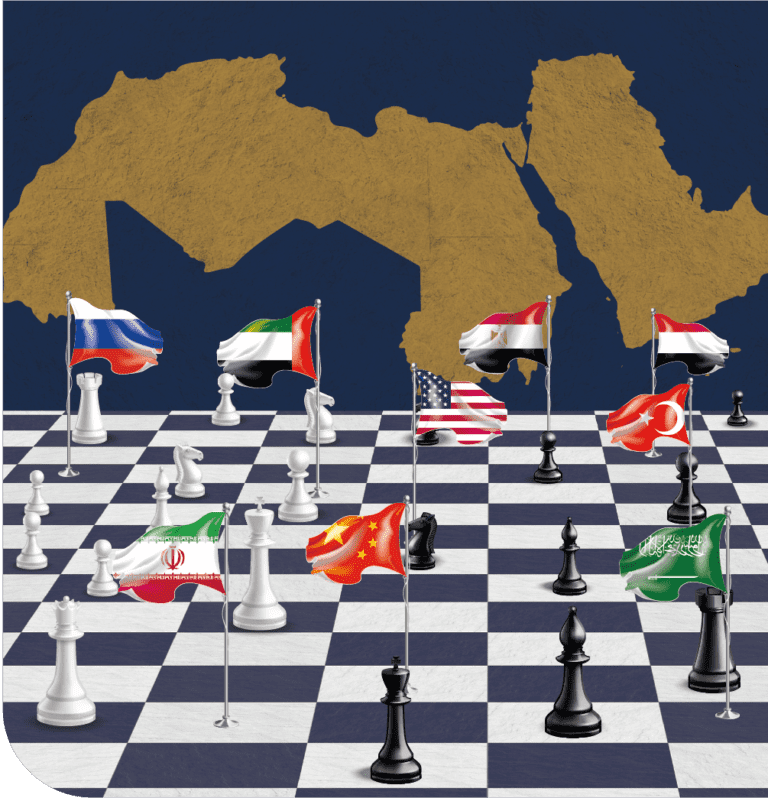

The Middle East as a Microcosm: The Middle East has already been a microcosm of Ankara’s new economy driven outlook. Türkiye’s warming ties with various Gulf states remain on track, and the economy has a central place in this rapprochement.

Triangle of Türkiye, Russia, and the West: Türkiye will strive to maintain its geopolitical balancing act between Russia and the West. However, this will preclude Ankara-Moscow defense cooperation. Türkiye’s rising interest in the “Turkic world” will also likely mean greater competition with Moscow. Conversely, Ankara’s ties with the West are improving, despite unresolved crises.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Growing Role: With a trusted and powerful name—Hakan Fidan—at its helm, the role of the Turkish foreign ministry in formulating policy will grow relative to other institutions. Turkish diplomacy is also likely to become increasingly professional in language and style.

Introduction

The course of Turkish foreign policy has witnessed major developments, with far-reaching implications, over the past year. Firstly, following his victory in the May 2023 presidential and parliamentary elections, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan appointed well-regarded figures—Hakan Fidan and Ibrahim Kalin, respectively—to the country’s top foreign policy and intelligence roles. Secondly, the region-wide trend of normalization with Israel, which had included Türkiye, came to an abrupt halt with Hamas’ attack on Israel on October 7th and Israel’s ensuing invasion of Gaza. Thirdly, after years of crises and tensions, a newly positive climate has come to permeate Türkiye’s relations with the West, which could also impact the trajectory of Turkish-Russian relations. Finally, Turkish foreign policy has had to chart its course against the backdrop of deepening domestic economic downturn. The time is therefore ripe for a closer examination of the cumulative impact of these developments on Turkish foreign policy and its overarching framework and trajectory, particularly towards the Middle East, Russia, and the West.

This issue brief argues that Türkiye’s quest for autonomy and status in international affairs, which has long characterized its foreign policy, is set to continue amidst these shifting dynamics. Turkish foreign policy will also increasingly be guided by economic considerations. In his debut article as foreign minister, Fidan emphasized that “the economic component of foreign policy will receive specific attention in the period ahead.”1 Türkiye’s economic woes will likely further accentuate this dynamic.

The Middle East has been a microcosm of this new economy-driven foreign policy. Türkiye’s ongoing rapprochement with the Gulf states was largely driven by economic considerations. However, Israel’s invasion of Gaza inevitably increased security and geopolitical considerations in Ankara’s regional policies and has already reversed the trend of normalization with Tel Aviv.

In the triangle of relations between Türkiye, Russia, and the West, Ankara will likely strive to maintain its geopolitical balancing act. However, the contents of the act are changing. For instance, Ankara is unlikely to engage in any new defense cooperation with Moscow, through purchasing sophisticated weapon systems, given existing tensions with the United States following Ankara’s 2017 purchase of the S-400 missile systems from Moscow, which caused a major rift with Washington.2

Türkiye-Russia ties are further complicated by the idea of the “Turkic world,”3 which is gaining increasing currency in Turkish foreign policy. Given that the imagined geography of the “Turkic world” encompasses Central Asia and the South Caucasus, the idea’s growing prominence in Turkish foreign policy could potentially fuel tensions with Russia, Iran, and China. Each of these powers have their own reason for concern. The Kremlin views the “Turkic world” as part of its near-abroad and natural zone of influence while Iran and China both host sizeable Turkic populations, Azeris and Uighurs respectively.

Moreover, structural crises such as the lack of a functioning framework for Türkiye–EU relations and fundamental disagreements that underlie Turkish–Western relations are unlikely to be resolved in the near future. Despite this, relations are on the mend as both sides become more skillful in managing disagreements and compartmentalizing issues. The thaw in Turkish–Greek relations, Ankara’s approval of Sweden’s NATO membership, and Washington’s approval of the sale of F-16 jets to Türkiye reflect this new climate.4

Persistence of the Quest for Strategic Autonomy

Ankara’s quest for autonomy in its foreign and security policy, a greater role in regional politics, and a higher status in international affairs form the overarching framework of Türkiye’s contemporary foreign policy, and this is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future. Indeed, Türkiye is both reflecting and spearheading a powerful trend in global politics—middle powers demanding a larger role in the affairs of their regions, autonomy in their foreign policy, and status in global politics.5

Regional actors’ policies towards the invasion of Ukraine are a case in point. To the chagrin of the West, many non-Western powers, such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Israel, South Africa, Brazil, and India, adopted policies of neutrality, informed by their quest to chart independent foreign policies, and by disillusionment with the United States and the West more broadly. For many, particularly in the Middle East, this policy is also reflective of Russia and the United States’ changing place in regional affairs. Moscow has increased its footprint in regional security, particularly through its presence in conflict zones such as Syria and Libya since 2015. In contrast, the United States has shown a decreased appetite for regional security commitments. The perception that the United States is less predictable and reliable has become prevalent in the region, advancing doubts surrounding Washington’s attention to its traditional partners’ security concerns.6 The war on Gaza further demonstrated the lengths of the United States’ commitment to Israel, going as far as alienating many in the region and internationally. However, this is a unique case and the United States is unlikely to have similar commitments to the security of any other state in the region.

Concurrently, economic interests are playing a growing role in Ankara’s foreign policy.7 This is best illustrated by the increasing use of economic language in Türkiye–Gulf relations. Türkiye and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) inked a deal, on March 21, 2024, to launch negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement, building on Ankara and Abu Dhabi’s existing comprehensive economic partnership.8 This trend of linking geopolitical aspirations with economic needs, is mirrored by many in the region. Countries such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Kuwait have all announced ambitious national economic development visions.9 For Türkiye, domestic economic pressures are particularly acute, with a plummeting currency and inflation that stood at 65% in December 2023,10 which has led to economic considerations figuring heavily in Ankara’s Middle East policy.

A Middle East Reset Amid War on Gaza

Mirroring region-wide trends, normalization and de-escalation have defined Türkiye’s recent policy towards the Gulf, the wider Middle East, and Israel (prior to October 7). This policy has mainly been driven by economic imperatives, the United States’ reduced security footprint in the region, a stalemate in regional conflicts, and the need to navigate a new regional reality where Arab Spring-era rivalries, alliances, and political-ideological trends have lost steam.11 Regional economic cooperation and connectivity are defining features of this strategy. With its economy in tatters, Ankara is aiming to attract Gulf states’ capital and investment through mending ties with its former rivals.

This policy appears to be paying off. During a July 2023 tour of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE, Erdoğan signed numerous deals including agreements with Abu Dhabi alone worth $50.7 billion.12 He also clinched various contracts in Riyadh, including a lucrative deal to sell drones to the Kingdom.13 Looking ahead, this policy of bridge-building with former Middle Eastern rivals is set to continue, with implications for conflict zones. Tensions in Libya, the Eastern Mediterranean, and Syria have eased. Simultaneously, geopolitical competition between Türkiye and regional powers such as Egypt, the UAE, and Greece have also abated, even if these crises remain far from resolved. There is also increased dialogue between Ankara and its former geopolitical rivals,14 although its rapprochement with Israel came to an abrupt stop following the war on Gaza.

Israel’s war on Gaza, and the resultant humanitarian catastrophe, marked a watershed moment in regional affairs, with major impacts on the dynamics of escalation, de-escalation, and normalization. The process of Israel’s normalization with the region, with no regard to—or at the expense of—the Palestinians, is firmly on hold, at least for the foreseeable future. While Saudi Arabia has repeatedly affirmed that it is not shelving the idea of normalization, it continues to demand that the question of Palestinian statehood be included in any such process.15 The thaw between Ankara and Tel Aviv and their cooperation in the Eastern Mediterranean and South Caucasus are also now largely obsolete.

Dismayed at the West’s unreserved support for Israel, Ankara has focused on regional diplomacy and tried to internationalize the conflict as much as possible, hoping for deeper involvement by non-Western powers and international institutions. Plus, unlike the propensity of many Western states to, at times, approach the Palestinian issue solely as an Arab matter, Ankara wants to create a wide international constituency for Palestinian rights and statehood. To that end, Fidan visited several regional and international capitals, shortly after the war started, advancing the idea of a multiparty guarantor system,16 with Türkiye, a number of Arab states, and international actors serving as guarantors for a settlement. Türkiye was also one of the main backers of an Arab-Islamic summit, held in November 2023 in Riyadh, that gave rise to a group of seven countries tasked with leading international efforts to create momentum for a ceasefire and put a stop to the war.17

Throughout this process, Türkiye has supported and complemented efforts by key Arab states such as Qatar, Egypt, and to some extent Saudi Arabia, rather than overshadowing or competing with them. In this sense, the war has further reinforced the process of normalization between Türkiye and the Gulf states. This marks a break with the dynamic prevalent during the Arab Spring, when Ankara played to the perceptions and aspirations of Arab streets rather than those of Arab elites, causing major crises in its relations with many Arab states. Türkiye now appears to have returned to its pre-Arab Spring regional policy of balancing its appeal to Arab masses with the need to maintain closer relations with their rulers to bolster regional cooperation.

The war on Gaza has also eased frictions with Iran, at least for the time being. Prior to October 7, Tehran regarded the prospect of Turkish-Azerbaijani-Israeli cooperation in the South Caucasus with alarm. However, this trilateral cooperation has been rendered obsolete by Israel’s aggression, at least in the near future. Since the war, Ankara and Tehran have exchanged a growing number of official visits,18 which is likely to continue for some time as Israel’s invasion of Gaza dominates the regional and international agenda. However, once the war subsides, the competitive dynamics of Turkish–Iranian relations will likely re-emerge particularly since the geographic scope of this rivalry is expanding, encompassing Central Asia, the South Caucasus,19 Iraq, and Syria. Tehran sees the emerging regional order in the South Caucasus as decidedly inimical to its interests. These fears are compounded by the idea of the “Turkic world’s” growing importance in shaping Turkish foreign policy. Iran, which hosts a sizeable Azeri population, views this as both a geopolitical and national challenge. Ankara’s backing of regional connectivity projects, such as the Middle Corridor, which aims to connect China with Europe via Central Asia, the Caspian Sea, the South Caucasus (Azerbaijan and Georgia), and Türkiye, has also caused consternation in Tehran.

Finally, despite the increasing prominence of economic factors in guiding Turkish foreign policy, security considerations will continue to be pronounced in Türkiye’s immediate neighborhood, namely Syria and Iraq. Ankara will maintain its military operations against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), particularly in Iraqi Kurdistan. Indeed, Ankara has held many talks in recent months with both Baghdad and Erbil, the capital of Iraq’s autonomous Kurdistan region, on taking joint measures against the PKK. Earlier this year, Türkiye’s foreign minister, defense minister, and chief of intelligence met with their Iraqi counterparts in Baghdad.20 One outcome of these talks was Iraq’s designation of the PKK as a banned organization.21 Despite a decrease in their intensity, Türkiye’s attacks on PKK affiliates in Syria,22 either directly or through Syrian opposition groups, will likely persist. There is therefore considerable potential for flare-ups and escalation in Syria and Iraq.

Shifting the Balance in Türkiye–Russia Relations

After 2016, Turkish-Russian relations entered a new era driven by geopolitical imperatives and shared discontent with the West and underpinned by a strong personal rapport between Erdoğan and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin.23 Three factors, in particular, characterized this new phase. Firstly, Türkiye engaged in defense industry cooperation with Russia, purchasing Russian-made S-400 missile systems, which prompted the United States to impose sanctions through the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) and the removal of Türkiye from the F-35 fighter jets program in 2019.24

Secondly, Ankara and Moscow have closely cooperated on regional conflict management, from Syria and Libya to Nagorno-Karabakh.25 The Syrian crisis especially has been central to molding Turkish-Russian relations. While the conflict has driven Türkiye and the United States apart, particularly due to the latter’s support for the People’s Defense Units (YPG), a Syrian affiliate of the PKK, it brought Türkiye and Russia closer.26 In early 2017, Ankara, Moscow, and Tehran launched the Astana process. This track sidelined the United Nations-led Geneva process.

Thirdly, Ankara and Moscow have also been cooperating in sensitive and strategic areas which create long-term dependency. For instance, Türkiye’s first nuclear plant, Akkuyu, is being built by Russia’s Rosatom.27 Upon completion, the plant is expected to produce around 10% of Türkiye’s electricity, further increasing Türkiye’s dependence on Russia as other countries seek to reduce dependence on Russian energy.28 Rosatom will operate the plant for 25 years, making the plant Russian constructed and operated.29

Moving forward, Ankara and Moscow are unlikely to further engage in defense cooperation; Türkiye will likely avoid purchase of additional sophisticated weaponry from Russia, given the exorbitant total costs of the S-400 systems, in political, economic and security terms. Similarly, it will probably refrain from cooperating further with Russia in sensitive and strategic areas such as nuclear power. However, they will maintain cooperation on geopolitical issues. That said, the intensity of their cooperation across conflict zones in the Middle East, such as in Syria and Libya, will likely decline, as these conflicts continue losing steam.

Beyond the Middle East, both will likely continue to engage in the South Caucasus and the Black Sea, or post-Soviet space in general. With aims to disincentivize Ankara from alignment with the Western position on Russia, Moscow has facilitated different roles for Türkiye to play in the war on Ukraine. For instance, Türkiye facilitated a prisoner swap between the United States and Russia in April 2022.30 The exchange of Russian pilot Konstantin Yaroshenko for U.S. ex-marine Trevor Reed took place in Türkiye.31 Later that year, the Turkish National Intelligence Organization (MIT) hosted the heads of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service, Bill Burns and Sergey Narshkin respectively, for a meeting in Ankara.32 Türkiye, alongside the UN, also played a key role, in brokering the Black Sea grain deal with Russia and Ukraine, which was vital to alleviating global food insecurity at the time. After Russia unilaterally withdrew33 from the deal, in July 2023, Ankara pursued energetic diplomacy to bring Moscow back on board and devised a new package of proposals along with the UN to revive the deal, but to no avail.34 Ankara’s close relations with Moscow and Kyiv allow it to play multiple roles.

However, the idea of the “Turkic world’s” increasing importance in Turkish foreign policy could fuel tensions between Ankara and Moscow. The area considered by Ankara as part of the “Turkic world” is regarded by Moscow as its backyard, post-Soviet space. Hence, this will likely further drive the competitive dynamics of Turkish – Russian relations. Despite growing strains, Ankara will strive to maintain functional relations with Moscow.

Turkish–Western Relations Improve, but Underlying Crises Remain

Conversely, Türkiye –West relations will likely improve. Türkiye’s new foreign and security policy decision-makers’ professionalism, the resolution of the crisis over Sweden’s NATO bid and the U.S. approval of F-16 jet sales to Türkiye35 all signal warming Türkiye-West ties. Reduced tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean and the concomitant thaw in Türkiye’s relations with Greece has also been key. Both Ankara and Athens display a clear willingness to reduce tensions, and heated exchanges have now been replaced by a new language that focuses on good neighborliness36 and cooperation, including Erdoğan suggesting nuclear energy cooperation.37 Given the importance of the Eastern Mediterranean for the EU, this reduction in tensions will bear positive repercussions for Türkiye–EU relations.38

However, despite an improved climate, the fundamental problems and challenges that underlie Turkish–Western ties are unlikely to change or disappear. There is a marked difference between Türkiye and the United States when it comes to their reading of global politics and great power competition. Ankara arguably sees the existence of multiple centers of power as a positive development, believing that it increases its own room for maneuver in its relations with the West. This can be seen in Syria where Türkiye and the United States’ threat perception is diverging. Moreover, Ankara is not alarmed by the rise of China, as opposed to the United States.

Europe’s geopolitical blindness coupled with Türkiye’s democratic backsliding only further deepen the dysfunctionality of the accession framework of Türkiye – EU relations. However, various potential avenues for future cooperation between Ankara and Brussels exist, such as migration, the energy transition, and geopolitical files, including security in Europe’s southern and eastern neighborhoods (albeit in a limited manner); however, fundamental constraints and differences in the relationship between Türkiye and the EU will likely limit prospects for cooperation.

The Foreign Ministry’s Role

Aside from region-specific changes in Turkish foreign policy, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is projected to play a pronounced role in directing foreign policy priorities and strategies. Three primary changes should be expected: institutional, stylistic, and ideological. Firstly, the foreign ministry’s importance in the policy-making process is set to increase. In recent years, policy was formed in an ecosystem made up of the presidency, the foreign ministry, the intelligence agency, and the military. The role of the ministry itself was previously arguably relatively less pronounced. However, under Fidan, a powerful name trusted by President Erdoğan, the role of the ministry is set to increase. Additionally, relatively enhanced diplomatic professionalism and institutionalism are likely to define the language and style of Turkish foreign policy.39

Finally, if operationalized in Ankara’s foreign policy, the aforementioned idea of the “Turkic world’s” growing prominence could increase strain on Türkiye’s relations with Iran, Russia, and China. Russia views the area encompassed by the “Turkic world,”40 be it in Central Asia or the South Caucasus, as its backyard, zone of influence, and geopolitical underbelly. At a time of great power competition between the West, Russia, and China, this conceptualization might fuel Russia-Türkiye tensions which could potentially lead to increased convergence between Türkiye and the West in that geographic space.

Conclusion

Türkiye’s foreign policy is set to continually adjust to changing regional and international contexts with its economic needs and woes featuring more prominently. However, the overarching framework of Türkiye’s foreign policy—the quest for status and autonomy—is unlikely to change in any major ways in the foreseeable future.

Endnote

1 Hakan Fidan, “Turkish Foreign Policy at the Turn of the ‘Century of Türkiye’: Challenges, Vision, Objectives, and Transformation,” Insight Türkiye, October 4, 2023, https://www.insightTürkiye.com/commentary/turkish-foreign-at-the-turn-of-the-century-of-turkiye-challenges-vision-objectives-and-transformation.

2 Amanda Macias, “U.S. sanctions Türkiye over purchase of Russian S-400 missile system,” CNBC, December 15, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/12/14/us-sanctions-Türkiye-over-russian-s400.html.

3 “Century of Türkiye is Century of Turkic world: Cavusoglu,” TRTWorld, March 1, 2024, https://www.trtworld.com/turkiye/century-of-turkiye-is-century-of-turkic-world-cavusoglu-17197170.

4 “US approves sale of F-16 fighter jets to Turkey,” AlJazeera, January 27, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/1/27/us-approves-sale-of-f-16-fighter-jets-to-turkey#:~:text=The%20%2423bn%20deal%20was,Sweden’s%20long%2Ddelayed%20NATO%20membership.&text=The%20United%20States%20has%20approved,week%20ratified%20Sweden’s%20NATO%20membership..

5 Galip Dalay, Deciphering Türkiye’s Geopolitical Balancing and Anti-Westernism in Its Relations with Russia (Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik), May 20, 2022, https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2022C35/.

6 Galip Dalay, Russia’s Ebbing Grip: What the Ukraine War Means for Moscow in the Middle East, Issue Brief (Doha: Middle East Council on Global Affairs, September 2023), https://mecouncil.org/publication/russias-ebbing-grip-what-the-ukraine-war-means-for-moscow-in-the-middle-east/.

7 Galip Dalay, How will geopolitics shape Türkiye’s international future? (London: Chatham House, June 5, 2023), https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/06/how-will-geopolitics-shape-Türkiyes-international-future.

8 “Türkiye and Gulf states to launch talks for free trade pact,” Reuters, March 21, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/Türkiye-gulf-states-launch-talks-free-trade-pact-2024-03-21/.

9 Sanam Vakil, Visions, Technocrats, and the Shifting Social Contract in the Gulf Countries, (Italian Institute for International Political Studies, May 26, 2022), https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/visions-technocrats-and-shifting-social-contract-gulf-countries-35194.

10 Muhammet Mercan, Turkish inflation rises in December (Amsterdam: ING, January 3, 2024), https://think.ing.com/snaps/Türkiye-inflation-up-in-december.

11 Galip Dalay, Türkiye’s Middle East Reset: A Precursor for Re-Escalation? Policy Paper (Doha: Middle East Council on Global Affairs, August 2022), https://mecouncil.org/publication/Türkiyes-middle-east-reset-a-precursor-for-re-escalation/.

12 Rachna Uppal and Yousef Saba, “Türkiye’s Erdoğan signs $50 billion in deals during UAE visit,” Reuters, July 19, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/Türkiyes-Erdoğan-ends-gulf-tour-with-abu-dhabi-visit-2023-07-19/.

13 “Türkiye’s Erdoğan strikes drone deal with Saudi Arabia on Gulf tour,” France 24, July 18, 2023, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20230718-saudi-deal-for-turkish-drones-during-Erdoğan-visit.

14 “Turkey, Syria, Russia, and Iran in highest- level talks since Syrian war,” Reuters, May 10, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/turkey-syria-russia-iran-hold-highest-level-talks-since-syrian-war-2023-05-10/.

15 Melanie Lidman and Wafaa Shurafa, “Saudi Arabia Won’t Normalize Relations With Israel Without Path to Palestinian State, Foreign Minister Says,” TIME, January 22, 2024, https://time.com/6564983/saudi-arabia-israel-palestinian-state/.

16 Tugba Altun, Busranur Koca and Sumeyye Dilara Dince, “Türkiye proposes guarantor formula for Israeli-Palestinian issue: Turkish foreign minister,” Anadolu Agency, October 17, 2023, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/turkiye/turkiye-proposes-guarantor-formula-for-israeli-palestinian-issue-turkish-foreign-minister/3022412.

17 “Joint Arab and Islamic Summit Concludes and Demands End to Israeli Aggression, Breaking of Israeli Siege on the Gaza Strip and Persecution of Israel for its Crimes,” Organization of Islamic Cooperation, November 13, 2023, https://www.oic-oci.org/topic/?t_id=39923&t_ref=26755&lan=en.

18 “Iran’s Raisi set to meet Erdogan in Turkey in push to halt spread of Israel-Hamas war,” France24, January 24, 2024, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20240124-iran-s-raisi-expected-in-turkey-for-delayed-gaza-talks.

19 Sinem Cengiz, “Turkish Iranian rivalry in the Caucasus undermines cooperation,” Arab News, September 8, 2023, https://www.arabnews.com/node/2369846.

20 Reuters, “Türkiye, Iraq hold security talks in Baghdad, Iraqi government says,” March 14, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/Türkiye-discuss-common-understanding-security-with-iraq-official-2024-03-14/

21 Ibid.

22 Daren Butler and Huseyin Hayatsever, “Turkey strikes Kurdish militants in Iraq and Syria,” Reuters, January 16, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkey-launches-airstrikes-against-militants-iraq-syria-2024-01-16/.

23 Galip Dalay, Türkiye’s next leader may be pro-West but not anti-Russia, (London: Chatham House, May 12, 2023), https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/05/Türkiyes-next-leader-may-be-pro-west-not-anti-russia.

24 “The U.S. Sanctions Türkiye Under CAATSA 231,” U.S. Embassy in Greece, December 14, 2020, https://gr.usembassy.gov/the-united-states-sanctions-Türkiye-under-caatsa-231/.

25 Galip Dalay, Turkish-Russian Relations in Light of Recent Conflicts Syria, Libya, and Nagorno-Karabakh, Research Paper 5 (Berlin: German Institute for International and Security Affairs, August 2021), https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2021RP05/.

26 Ibid.

27 Andrew Wilks, “Turkish nuclear plant threatened by Russian sanctions,” Al Jazeera, May 16, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/5/16/turkish-nuclear-plant-threatened-by-russian-sanctions.

28 Reuters, “Türkiye seeks to resolve dispute over Russian-built nuclear plant,” August 3, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/Türkiye-seeks-resolve-dispute-over-russian-built-nuclear-plant-2022-08-03/.

29 Wilks, “Turkish nuclear plant threatened.”

30 “Russia frees ex-US marine Trevor Reed in prisoner exchange,” Al Jazeera, April 27, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/4/27/russia-says-freed-ex-us-marine-trevor-reed-in-prisoner-exchange.

31 “Ex-marine Trevor Reed freed from jail in dramatic US-Russia prisoner swap,” The Guardian, April 27, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/27/us-russia-prisoner-exchange-trevor-reed-moscow-yaroshenko.

32 “US, Russian spy chiefs met in Turkish capital, say intelligence sources,” Anadolu Agency, November 14, 2022, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/politics/us-russian-spy-chiefs-met-in-turkish-capital-say-intelligence-sources/2737844.

33 “UN chief regrets Russia’s decision to withdraw from grain deal,” United Nations, July 17, 2023, https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/07/1138752.

34 Muhammed Enes Çallı, “Turkish foreign minister says new UN proposals could revive Black Sea grain deal,” Anadolu Agency, August 31, 2023, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/russia-ukraine-war/turkish-foreign-minister-says-new-un-proposals-could-revive-black-sea-grain-deal/2980448.

35 “US approves sale of F-16 fighter jets to Turkey,” AlJazeera, January 27, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/1/27/us-approves-sale-of-f-16-fighter-jets-to-turkey.

36 Helena Smith, “Erdoğan hails ‘new era’ of friendship with Greece on historic visit to Athens,” The Guardian, December 7, 2023,

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/dec/07/Erdoğan-hails-new-era-of-friendship-with-greece-during-historic-visit-to-athens.

37 “Erdoğan says Türkiye, Greece could cooperate on nuclear energy,” Reuters, December 9, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/Erdoğan-says-Türkiye-greece-could-cooperate-nuclear-energy-2023-12-08/

38 “EU calls Türkiye ‘key’ partner amid thaw with Greece,” Daily Sabah, December 13, 2023, https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/eu-affairs/eu-calls-turkiye-key-partner-amid-thaw-with-greece.

39 Fidan, Turkish Foreign Policy.

40 Sinan Tavsan, “‘Turkic world’ wants a voice in the new global order,” Nikkei, November 13, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Turkic-world-wants-a-voice-in-the-new-global-order.