Russia’s Ebbing Grip:

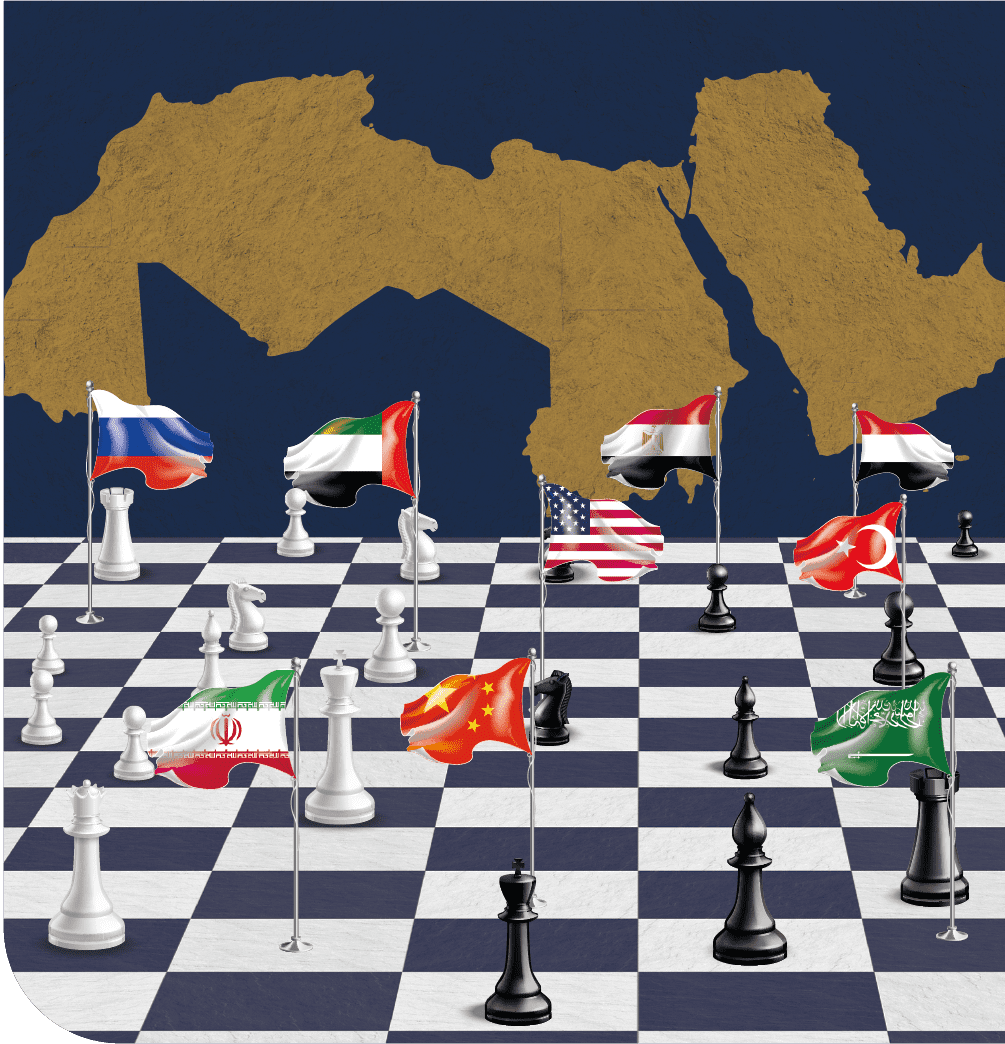

What the Ukraine War Means for Moscow in the Middle East

Issue Brief, September 2023

Key Takeaways

Russia’s Strategic Persistence: Amid the ongoing war, Russia’s role in the Middle East remains relatively stable. Moscow actively maintains its regional influence, especially evident in conflict zones like Syria and Libya. However, its leverage with regional actors is diminishing.

Incentives for Regional Neutrality: Russia employs incentives to encourage Middle Eastern nations to stick to their geopolitical balancing act on the war. By offering various roles to these states, Moscow aims to prevent alignment with Western stances and sanctions.

Middle East’s Active Neutrality: The regional states’ neutrality on the war does not signify a passive policy position or hands-off approach. Instead, it points to active diplomacy. Plus, the war has presented the regional countries with an opportunity to showcase their international stature and deepening ties with China, Russia, and India as well as with countries of the global south. In return, with such deepening and diversification of relations with non-western global powers and global south, regional countries believe that their importance for the West is set to increase.

Global Narrative vs. Regional Optic: On the Ukraine war, the West has largely adopted a global narrative. However, it is the regional-level dynamics that have primarily informed the policy of non-Western actors. The policies of Middle Eastern actors are reflective of the evolving place of the United States and Russia in regional affairs and security as well as their discontent with the United States.

Revivifying the West and non-West Alike: The war has revived the West and NATO. It increased the internal coherence of the alliance and gave it a new sense of purpose. However, the war has also revived the idea of global south and neutrality in international affairs. The Middle Eastern actors are trying to capitalize on this momentum. The case in point is that of the six new members of the BRICS club, four of them are from the Middle East.

Russian influence is set to wane, as the war drags on: Despite Russia’s influence and temporary jump in trade volume with the region, as the war grinds on and Russian-Western confrontation and associated isolation deepens, Russia’s regional influence is likely to gradually wane. Contributing to this will be the growing strains on Russian resources as a result of the invasion and the lackluster performance of Russian weaponry in Ukraine.

Introduction

The war in Ukraine represents a watershed moment in international affairs. It has brought great power rivalry and power politics to the fore of global politics. It redefined the nature of relations between Russia and the West and informed North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)’s strategic documents and security concepts, putting Moscow decidedly in the alliance’s enemy camp.

Similarly, this war also represents a pivotal moment in Russia’s policy towards the Middle East. Since its military intervention in Syria’s conflict in September 2015, Moscow has steadily increased its profile and presence in regional affairs, not least in regional security. It has played a crucial role in regional conflict zones, be it in Syria or Libya, and formed closer ties with regional powers. This was happening at a time when the United States’ regional influence was arguably waning, and relations with traditional regional partners such as Türkiye, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have become increasingly crisis ridden. Moscow and Washington’s changing place in regional affairs has informed regional states’ policy towards the Ukraine invasion. To the chagrin of the West, regional countries engage in a balancing act between Russia and the West on the war, driven by regional states’ geopolitical imperatives and discontent with the United States.

This issue brief argues that the war has thus far not changed Russia’s position in the Middle East in any significant way. Moscow strives to maintain its place and influence in regional geopolitics as much as possible. Plus, Moscow incentivizes these states to maintain their balancing act—hence not joining the Western position and sanctions—by facilitating different roles for them as the war lingers on. Despite this picture, the war grinds on and Russia’s international isolation deepens. This brief argues that Russian influence is likely to gradually wane and the prestige of Russian weaponry declines in the Middle East.

The Roots of Middle Eastern States’ Balancing Act

The balancing act of the Middle Eastern states is an outgrowth of multiple interrelated factors. First, this policy signals discontent with the West, not least the United States. Over the last decade, particularly in recent years, the gap between the United States and many Middle Eastern states is growing. The cases in point are Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Türkiye. These states appear to believe the United States is not as attentive to their security needs. For instance, Riyadh seems to believe the United States does not take its security concerns vis-a-vis Iran, Yemen, and the Houthi attacks on Saudi soil seriously.1 Similarly, Türkiye sees the U.S. support for the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD)/ the People’s Protection Units (YPG) as posing a direct threat to its national security.2 Further, Ankara saw U.S. support for what previously seemed to be an emerging energy and security framework in the Eastern Mediterranean, which excluded Türkiye, as a soft-containment policy pursued by Washington DC towards itself.3 The logic of quid pro quo is at play here. For many regional states, if the United States is not as forthcoming on their security concerns, they are not as responsive to U.S. demands and desires. Therefore, among other things, the geopolitical balancing act signals discontent with the United States.4

Second, Russia’s growing presence in the region and close ties with many regional states also informs this balancing policy. Since its military intervention in Syria in 2015, Moscow has only expanded its regional security role through different conflict zones, notably in Syria and Libya,5 but also in Nagorno-Karabakh.6 Though this latter crisis is not directly in the popularly accepted Middle Eastern geography, it nevertheless represents a new front in Middle Eastern geopolitical competition, not least between Türkiye, Iran, Israel as well as Russia. Whereas Türkiye and Israel support the Azerbaijani side—particularly by providing armed drones7—Iran did the same for Armenia8—a factor that is straining Baku-Tehran ties.9 In Turkish-Iranian competition, the South Caucasus and Middle East should be seen as an integrated space rather than two different regions.

Moscow’s growing role in regional conflict zones or conflict management has increased its interactions with regional states such as Türkiye, Iran, the UAE, Egypt, or Israel. For instance, Syria is an issue of national security for Türkiye, Iran, and Israel. Russia skillfully uses its role in Syria to create dependency or close ties with these states. Through the Astana process—which Türkiye, Russia, and Iran launched in the closing days of December 2016—the three actors engaged in an extensive degree of conflict management. In fact, through this initiative, they redesigned the country’s conflict map in a more profound way than the UN-led Geneva process could.10

Türkiye has recently expressed its openness to normalize ties with the Assad regime.11 Again, Russia has situated itself as a gatekeeper for any prospective normalization—the first foreign ministers meeting between Türkiye, Russia, Syria, and Iran took place in Moscow on May 10, 2023.12 At a time when the Astana process had largely run its course, Moscow, Ankara, Tehran and Damascus created a quartet to pave the way for Türkiye-Syria normalization, which at best is barely on the horizon. Syria has also become an active front in Iranian-Israeli confrontation. Israel has attacked many Iranian and Hezbollah targets in the country.13 Given the Russian role in Syria, Israel needs to maintain good ties with Moscow.

Russia: Leveraging Security Role through Conflict Zones

At the outset of the Ukraine war, there were questions over whether Russia can maintain its presence or level of engagement Syria’s conflict. The related question was if Moscow had to downsize its presence in Syria, who would fill this void and how would this affect Russia’s position in the region? The passage of time has illustrated that Russia has not withdrawn from Syria in any meaningful way. Moscow’s decisive role in this conflict has become a status symbol in itself—a great power that can fundamentally chart the course of a major international crisis and preserve its interests in Syria.

Therefore, failure in or withdrawal from Syria was not an option for Russia. Despite this, the Ukraine war put strains on Russian resources. In response, Russia shifted its focus to its main interests in western Syria and downsized its presence in central Syria, where, arguably, Russia’s role is being taken over by Iran and Iran-aligned militias.14 In southwest Syria, an area of strategic importance to Israel, Iran also appears to have a more significant presence recently.15 In line with such redeployment and considering Russia’s limited presence in central and southwest Syria, “Iran is expected to increase its economic and political influence” there.16 Plus, whenever tested, Moscow asserted its role in Syria. For instance, in July 2022, Moscow dispatched an additional battalion of paratroopers and air-defense assets to northern Syria after Türkiye signaled that it might undertake another military incursion in the area.17

According to recent statements by the top U.S. Air Force commander in the Middle East, Lt. Gen. Alex Grynkewich, the size of Russia’s military presence in Syria has mostly leveled off after the initial redeployments.18 Thus, by clinging to its role in Syria, albeit in an adjusted manner, Moscow maintains sources of leverage and forms of interdependency with regional states, which have an impact on these countries’ policies towards the Ukraine war. Yet the prolongation of the Ukraine war is likely to gradually strengthen the hands of regional states in their dealings with Moscow.

A similar logic is probably at play between Russia and regional actors such as Egypt, the UAE, and Türkiye that are active in Libya’s conflict. Like Cairo and Abu Dhabi, Moscow has also supported the forces of self-styled Field Marshal Khalifa Hifear, i.e., the Libyan National Army (LNA). Moscow has also maintained open channels with west Libyan actors and has a military presence, largely through the Wagner Group on the ground. Plus, prior to the Berlin Conference on Libya on January 19, 2020, Ankara and Moscow tried to launch a diplomatic process, but to no avail as Khalifa Hifter left Moscow without signing the joint memorandum engineered by Ankara and Moscow.19 In other words, by capitalizing on their experience in Syria, Russia and Türkiye tried to pre-empt Western actors for a diplomatic process on Libya. Yet, this quest remained unfulfilled.

Through its military and diplomatic might as well as a web of relations with regional actors, Moscow has been an influential external actor in Libya’s conflict. The start of the Ukraine war coincided with a period of regional normalization between erstwhile rivals in the Middle East. This de-escalation has been amply on display in Libya where all rival external actors have refrained from escalating tensions. Such a lull or de-escalation in the conflict has relatively lessened the impact of the war on Russian presence in Libya. However, given the considerable presence of the Wagner forces in the country, the recent Wagner mutiny in June and the death of its chief, Yevgeny Prigozhin, in a dubious plane crash on August 23 might have a deleterious impact on Russia’s role in Libya.20

Despite these two developments, when formulating their policy towards Russia amidst the war in Ukraine, regional countries probably had to factor in the implications of these policies on their interests and presence in these regional conflict zones that have created different forms and degrees of security dependencies between Russia and these states.

Third, Russia and the regional states have cultivated closer economic and energy ties within the OPEC+ (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) framework, a grouping in which Saudi Arabia and Russia play dominant roles and engage in cooperation in strategic sectors, such as nuclear technology.21 As shown in figure 1, the war boosted economic links between Russia and several regional states. Indeed, these states probably want to capitalize on Russia’s growing isolation by trying to attract more Russian money and tourists. For instance, since the start of the war, Dubai has become the main destination for Russian fortunes. Wealthy Russians use Dubai “as a go-between for transferring money between Russia and Europe” after sanctions were imposed on Russia.22

In March 2022, the UAE was included on the “grey” list of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the global financial crime watchdog.23 Elizabeth Rosenberg, the assistant Treasury Secretary for terrorist financing and financial crimes, in March 2023, said that UAE was a “country of focus” for the United States.24 In March 2023, the UAE’s central bank cancelled Russian-owned MTS bank’s license to operate, after it was subjected to British and U.S. sanctions in February.25 The volume of trade between Russia and the UAE increased by 68% during 2022. This booming trade appears to result from the UAE’s re-export of goods that Russia could not acquire on the international market due to sanctions. The Emirati sale of electronic components to Russia—subject to multiple international sanctions—multiplied 15-fold during 2022.26

Figure 1. Russian Trade with GCC Countries (Millions of USD)

Source: International Monetary Fund Direction of Trade Statistics (DOTS).27

Incentivizing for Neutrality

Fourth, Russia also incentivizes regional states such as the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Türkiye to maintain their current policy in different ways, preventing them from throwing their lots in with Western actors. All these states are aspiring for international roles, prominence, and status. Moscow capitalizes on these aspirations and quests by allowing them to play different though limited roles in the war. For instance, Moscow appears to say yes to whoever wants to play a diplomatic or mediation/facilitation role, particularly in non-western world as it refused the prospect of Swiss mediation, which was called for by the Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy,28 citing the country’s loss of its neutrality by “adopting the European Union’s sanctions over the invasion of Ukraine and freezing Russian assets worth 7.5 billion Swiss francs ($8.36 billion).”29 This is not because Moscow is genuinely looking for a diplomatic resolution to the war, but because doing so serves Russian interests. For many non-Western countries, Russia is perceived as being open to a diplomatic resolution whereas the West comes across as uncompromising. This further drives wedges on Ukraine.

Middle East’s Active Neutrality on the War

To be more precise, several regional states such as Türkiye, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE have tried or still try to play a diplomatic role to bring the war to an end. Similarly, all three states have facilitated prisoner exchanges between Russia and Western states, not least the United States. According to the Saudi foreign ministry, Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler Mohammed bin Salman personally intervened in the release of ten international soldiers captured by Russia in Ukraine.30 The prisoners—five of whom were British and two U.S. citizens—were flown from Russia to Saudi Arabia before being freed.31 Even symbolically more significant, in August 2023, Saudi Arabia hosted a peace summit in Jeddah on the Ukraine war with representatives from 40 countries including the United States, China, several countries from the Global South, and members of BRICS bloc (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) excluding Russia,32 boosting its international stature and projecting autonomy in its foreign and security policy. This was the first time China attended such a summit—underscoring Riyadh’s close ties with Beijing—it did not attend similar talks in Copenhagen.33 Meanwhile, the UAE played a role in the release of U.S. basketball player Brittney Griner, detained in Russia shortly before the invasion of Ukraine. Griner was part of a prisoner exchange with Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout, who was detained in the United States. The exchange of prisoners took place in Abu Dhabi.34

Likewise, Türkiye facilitated a prisoner swap between the United States and Russia. The exchange of Russian pilot Konstantin Yaroshenko for U.S. ex-marine Trevor Reed occurred in Türkiye.35 Erdogan negotiated this exchange, for which both Washington and Moscow publicly thanked Ankara.36 In November 2022, Türkiye’s then chief of intelligence and current Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan also hosted heads of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service for a face-to-face meeting in Ankara.37 Similarly, in July 2022, Türkiye played a key role, along with the United Nations (UN), to broker the Black Sea grain deal with Russia and Ukraine, which is highly important in alleviating global food security. After Russia unilaterally withdrew from this deal on July 17, 2023,38 Ankara has pursued an energetic diplomacy to bring Moscow back on board and devised a new package of proposals with the UN to revive the deal.39 On September 4, 2023, Türkiye’s President Erdogan met with the Russian President Putin in Sochi to revive the grain deal. Moscow has not yielded on this point yet, insisting on its conditions for export of its own grain and fertilisers to the global markets to be met,40 not least “its state agricultural bank (Rosselkhozbank) and not a subsidiary of the bank, as proposed by the United Nations – to be reconnected to the international SWIFT bank payments system.”41 By allowing these states to play such roles, Russia incentivizes them to not get closer to the Western/U.S. position on the invasion.

Figure 2: Percentages of Wheat Imports from Russia and Ukraine (in value), 2020

Source: Arab Reform Initiative.42

Note: The selected Arab countries are the most dependent on wheat imports from Russia and Ukraine. This selection does not include oil net-exporters or oil exporters.

Finally, many non-Western states, including Middle Eastern ones, appeared to see this war through the prism of Russian-Western confrontation than Moscow invading Ukraine. The salience of the NATO dimension and the emphasis on the NATO-Russia hostility during the war have contributed to such thinking. Similarly, the Russian narrative of the war has excessively focused on the Western/U.S./NATO angles, depicting it as a Russian-Western conflict, to the point of almost denying Ukraine’s agency. As a result of such a depiction, many in the non-Western world see this war as a manifestation of great-power rivalry than a Russian invasion of Ukraine and a flagrant violation of its sovereignty.

Such framing has also informed both political elite and societal perceptions of this war in the Middle East and the larger non-Western world, where elites would probably be happy if Western hegemony in international affairs was being dented. This latter point is premised on the idea that if Western dominance in global politics is weakened, this would increase the autonomy and room to maneuver for regional actors, making the nature of their relations with the West/United States less hierarchical. Moreover, a significant number of people in the region utilize the history and memory of Western colonialism and double standards, be it the U.S. invasion of Iraq or Israel’s continued occupation of Palestinian land.

Waning Image

In spite of Moscow’s attempt to maintain its place in regional affairs, the Ukraine war has affected the attractiveness of Russia’s military equipment for regional countries. Some have argued that “the abysmal failure of Russian weapons to achieve front-line breakthroughs in Ukraine and secondary sanctions risks have prevented Moscow from striking new arms deals with Saudi Arabia or the UAE.”43 This picture is unlikely to be confined to the weapons deals between Russia and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. For instance, Türkiye previously purchased the Russian-made S-400 missile systems, which caused a deep rift in Türkiye-U.S. relations.44 However, after the lackluster performance of the Russian military hardware and equipment in Ukraine, Ankara is unlikely to repeat the purchase of other sophisticated weapons systems from Russia anytime soon. Moreover, Western countries are now further toughening up their sanctions on the Russian defense industry.45

Plus, Moscow’s military-industrial complex is primarily focused on serving the Russian military’s growing needs. As figure 2 illustrates, the share of Russia in the GCC’s weapons market has been very modest at best, if not negligible, when compared to Moscow’s arms trade with other regional countries, such as Algeria or Egypt. In short, this war has dented the prestige of the Russian defense industry and weapons. This factor, coupled with the Western sanctions and Russia’s domestic need, will likely deal a blow to Russia’s defense industry exports.

Figure 3. Value of Russian Weapons Exports to Selected Countries, 2013—22 (Millions of Trend Indicator Values, TIVs* ).

Source: SIPRI Arms Transfers Database.46

Notes:

* The trend-indicator value (TIV) does not represent sales prices for arms trades. It is a measure that permits comparison of volume of international transfers of major conventional weapons using a common unit.

** Oman data is null over the years, hence the total TIV with GCC countries does not include Oman.

As the war grinds on, the cost of the war for Russia grows exponentially and Moscow-West tensions and associated isolation deepens. This cost occurs on multiple levels such as military, economic, humanitarian, political, and diplomatic. For instance, it is difficult to establish the extent of Russia’s military equipment losses and the number of its casualties. However, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, “the levels of equipment losses experienced in Ukraine (by Moscow) are clearly unprecedented for post-Soviet Russia.”47 This in return means that Moscow’s hand is relatively weakened when dealing with regional powers in the Middle East and beyond.

As the war prolongs, these states would try to capitalize on Russia’s international isolation and difficulties—for example, one of the countries that has profited most from Moscow’s international woes and isolation is India by importing oil from Russia at highly discounted prices. Figure 3 illustrates India’s purchase of Russian oil before the war was limited, but the volume has multiplied since. Moscow might therefore have had the upper hand in dealing with regional powers prior to the war. However, since the war, these relationships are no longer as asymmetric in Russia’s favor as they used to be. Therefore, the question of dependency and asymmetry in Russia’s relationship with regional actors is dynamic and changes with new developments, not least with the war in Ukraine.

Figure 4. India’s Average Oil Import per Month from Russia (Millions of Barrels per Day)

Source: Bloomberg News, using data from Kpler.48

Lastly, the Wagner mutiny49 is another factor that potentially can negatively affect Russia’s place in the region, for two main reasons.50 First, this mutiny was a major blow for Russia/Putin’s image, increasing questions over the strength and future of Putin’s power. Given close relations between elite perceptions and policymaking, the view that Putin’s grip on power in Moscow might not be as secure as previously thought bodes ill for the Russian president’s position in regional politics.51 Wagner Group chief Yevgeny Prigozhin’s death as a result of a dubious plane crash only partially alleviates Moscow’s image problem stemming from this mutiny.

Second, from Syria to Libya to Sudan, Wagner has played an important role in Russia’s military adventures. To be more precise, the Wagner Group is opaque, which makes collecting data about them and their activity very difficult. However, according to a recent report prepared by the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee in the United Kingdom, “the network’s military operations can be mapped in at least seven countries (Ukraine, Syria, Central African Republic, Sudan, Libya, Mozambique, and Mali), with medium or high confidence that the network has been involved in a non-military capacity in 10 more countries since 2014.”52 Given this wide presence, it is clear that the group has been an important instrument of the Russian policy towards the conflict zones and fragile states. After the mutiny and death of the Wagner’s chief, there are many questions hanging over the group’s future. At this stage, it is only logical to anticipate that Russia will reduce the utilization of these fighters and replace them with alternative forces over time in these conflict or crisis zones, potentially forcing the Russian military to fill the gap that might emerge as a result.

To sum up, since the start of the Ukraine war, Russia has largely retained its role in the Middle East and regional actors are engaged in a geopolitical balancing act between Moscow and the West. As the war becomes more drawn-out, the associated cost and Russia’s isolation burgeons, Moscow’s bargaining power vis-a-vis regional actors diminishes. Looking to the future, the pressure on Russian resources and international relations will probably reduce Moscow’s regional role. However, a reduction in Moscow’s regional footprint would not necessarily translate into an increase in Western regional influence. Instead, regional actors are more likely to fill the gap themselves and continue to diversify their international relations by cultivating closer ties with the non-western global powers and countries of global south, while at the same time redefining their relations with the West, not least the U.S.

Endnotes