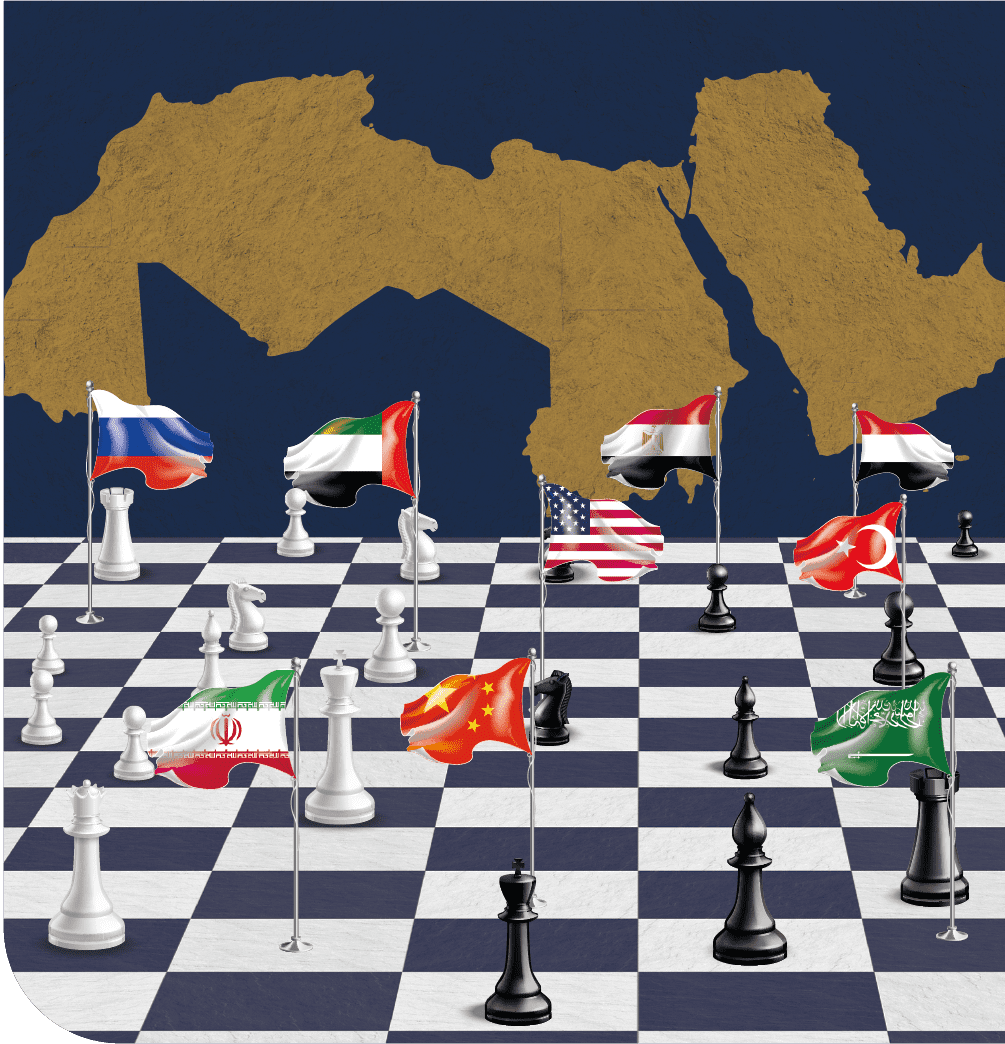

The Middle East's Fragile Reset:

Actors, Battlegrounds, and (Dis)order

Dossier, November 2023

Introduction

The question of (dis)order remains central to current debates on Middle Eastern politics and security. It is a multifaceted question with security, political, and economic dimensions and is intimately interlinked with the Middle East’s place in the changing global system and external powers’ relations with the region.

The domestic, regional, and external contexts of this question have dramatically changed over the last decade. Although the Arab uprisings have subsided, the social, political, and economic grievances that led to the political upheaval from 2011 to 2019 remain unaddressed, if not worsened. From the post-Arab Spring economic dislocation to the COVID-19 pandemic recessions and, more recently, to the cost-of-living crisis following the war in Ukraine, socioeconomic indicators outside the Arab Gulf have moved in reverse. A resurgence in military rule has interrupted political transitions and autocrats in power have tightened their grip on state institutions and public life. As a result, the region continues to underperform on metrics of corruption, transparency, and good governance.

Despite this static domestic picture, the regional and international contexts of Middle Eastern politics have experienced major changes. Specifically, the nature of intra-bloc dynamics and inter-bloc competition has undergone a major transformation. Indeed, setting aside the phase of the fierce geopolitical and ideological contests of the previous decades, regional diplomacy was experiencing an upswing until recently. Prior to the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, ensuing Israeli-Palestinian clashes, and Israel’s siege and invasion of Gaza, almost all regional countries were active participants in the ongoing process of regional de-escalation and normalization signaled by the Abraham Accords, the resolution of the intra-Gulf rift, the thaw in Türkiye’s relations with the Arab Gulf states, the restoration of diplomatic ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and the gradual re-integration of Syria into the regional system. Additionally, several regional and international actors, such as Iraq, Iran, and Russia, have offered their visions for some form of a regional order or security dialogue.

These different normalization initiatives encompassed almost all regional states. An exception has been the absence of de-escalation between Iran and Israel. Despite this, there is a significant difference between how the Arab–Gulf states and Israel want to deal with Iran. The Abraham Accords were decidedly anti-Iran. Likewise, the discontent with Iran’s regional policy was an implicit factor in Türkiye’s normalization with the Arab–Gulf states and Israel. However, the thaw in Iran’s relations with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and even precariously with Egypt have changed this picture, with Iran increasingly becoming an active participant in the realignment dynamics. In short, de-escalation, reset, and normalization were the fashionable vocabularies to describe this phase of regional politics then. The emerging regional language was less ideological, less geopolitical, and more economic. Regional conflicts were losing steam, albeit far from being resolved.

(…)

However, a caveat needs to be stressed. This dossier was completed before the eruption of the recent Israeli-Palestinian clashes and Israel’s invasion of Gaza. This war represents a watershed moment in regional affairs. It affects the process and dynamics of the regional reset, in particular the normalization of ties between Israel and regional states. To reflect this, Omar H. Rahman and Raffaella A. Del Sarto partially updated their chapters since they dealt directly with the Abraham Accords and the question of regional order. However, while the war in Gaza will certainly reshape the regional politics and policies of all main regional and international actors, the content, main themes, and arguments of all other chapters remain as valid and relevant. This project will nevertheless focus on how this war redefines regional politics and the question of regional (dis)order in its upcoming work in a more detailed manner.

Table of Contents

Introduction: Galip Dalay & Tarik M. Yousef

Section One: Regional (Dis)Order

Chapter 1: A Region in Transition: The Fluid Nature of Middle East Politics – Raffaella A. Del Sarto

Chapter 2: Locally-led Regional Alliances and the Future of Middle Eastern Security: Exploring the Role of Novel Security Frameworks – Rory Miller

Chapter 3: The Geopolitics of Energy: OPEC+ and the Challenges of the New Energy Order – Nicolay Kozhanov

Chapter 4: Normalization and Its Flaws: Moving from the Abraham Accords to Arab-Iranian Rapprochement – Omar H. Rahman

Section Two: Regional Power Players

Chapter 5: Regional Powers and the Regional Reset – The Case of Saudi Arabia – Christian Koch

Chapter 6: Navigating Power Dynamics: Iran’s Foreign Policy amid a Middle East Reset – Hamidreza Azizi

Chapter 7: Turkish Foreign Policy and the Middle East Order – Taha Ozhan

Chapter 8: Redefining Priorities: Small States’ Foreign Policy in a Changing Middle East – Anna Jacobs

Section Three: Multipolarity and Great Power Competition

Chapter 9: Russia in the MENA Region Amid the Ukrainian Crisis – Andrey Kortunov

Chapter 10: China’s Global Security Initiative: Bridging Divides in the Middle East – Jin Liangxiang

Chapter 11: Rivalry and Realignment in the Middle East: How Will the U.S. Respond? – Richard Outzen

Chapter 12: Europe’s Evolving Role in a Changing Region – Tobias Borcki

Section Four: Battlegrounds

Chapter 13: Syria’s Regional Rehabilitation: Between Consensus and Competition – Sinan Hatahet

Chapter 14: Iraq Benefiting from Regional Reset – Kamaran Palani

Chapter 15: Libya: The Canary of MENA’s Normalization – Tarek Megerisi

Chapter 16: Pathways to Peace in Yemen – Nader Kabbani

Conclusion – Galip Dalay & Tarik Yousef