After the World Cup:

Building a World-Class Public Administration in Qatar

Policy Note, June 2023

At his first meeting with the Council of Ministers in April 2023, Qatar’s new Prime Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani articulated a clear set of priorities for Qatar’s public sector. They include managing the state and its resources to achieve the greatest efficiency and productivity; providing high-quality services to citizens, residents, investors, and tourists; and diversifying the employment of Qatari nationals away from the public sector.1 It is an ambitious yet appropriate agenda.

As it currently stands, Qatar already performs well on a number of global governance indices, ranking at or near the top of all other countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). It ranks second in the region in the World Bank’s latest Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) metric for government effectiveness; second on the WGI indicator of regulatory quality; and second among Arab nations (and 40th globally) on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.2 Qatar’s fiscal position is also healthy. Natural gas prices are robust, and the country is opening new markets in Europe that will guarantee strong revenue streams for years to come.

A less ambitious administration might be content to sit back and let the good times roll. Yet the prime minister is wise not to be too complacent. While Qatar scores well on a number of global governance metrics, there are others where the country is lagging behind. Qatar falls in the muddled middle of MENA countries and no better than 78th globally in the U.N.’s most recent e-Government Development Index.3 It was in a similar position in the World Bank’s last Doing Business report and rankings in 2020.4 And it performs poorly on transparency metrics. Qatar scored two out of a possible 100 on the Open Budget Partnership’s Open Budget Index and was second to last in the region.5 Meanwhile, other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries—particularly the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia—have embarked upon ambitious public sector reform agendas that, if successful, could revolutionize how their governments operate. They have already achieved impressive success in several areas. For example, reflective of gains in e-government development, Dubai is currently ranked fifth in the world in the U.N.s’ Local Online Services Index, tying with New York and Paris and ahead of Singapore, Tokyo, and Zurich.6

Yet global rankings tell only part of the story. The International Monetary Fund’s most recent Article IV consultations in 2022 noted that, while Qatar’s near-term economic picture was positive, a number of risks cloud the medium-term outlook.7 These include an uncertain global economic path in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, volatile hydrocarbon prices, tighter global financial conditions, and geopolitical tensions.8 These risks have now materialized and may extend for longer than initially forecast. The regional context in the GCC is also changing, with growing economic competition and limited policy coordination. In this new environment, Qatar’s reform agenda has become more pressing and complex.

Improving Public Expenditure Management

The first priority identified by the prime minister—strengthening the efficiency and productivity of government expenditure—will require significant improvements in public expenditure management. Qatar’s revenues and expenditures have historically experienced “boom-and-bust” cycles that have undermined steady improvements in administrative efficiency. To smooth out these fluctuations, the country needs a rules-based, counter-cyclical fiscal policy and a medium-term fiscal framework. Significant improvements in public investment management will be required to achieve greater efficiency and to maintain Qatar’s world-class infrastructure. Other GCC countries, such as Saudi Arabia, have recently established special units for analyzing recurrent and capital expenditure in sophisticated ways that can simultaneously boost performance while reducing costs.9 Qatar would be wise to study and emulate this experience.

One of the best ways to begin Qatar’s public financial management reforms would be to conduct a systematic benchmarking exercise. The Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) framework provides an ideal tool for this task.10 PEFA was initiated collaboratively in 2001 by leading financial and development institutions—including the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and several bilateral development agencies—with the goal of harmonizing the assessment of public financial management institutions and practices. The PEFA assessment has seven main dimensions: (1) budget reliability; (2) transparency of public finances; (3) management of assets and liabilities; (4) policy-based fiscal strategy and budgeting; (5) predictability and control in budget execution; (6) accounting and reporting; and (7) external scrutiny and audit.

As of April 2023, over 155 countries have conducted PEFA assessments, including 12 countries in the MENA region. In all, 30 assessments have been performed in MENA,11 with a number of countries such as Morocco, Jordan, and Tunisia having undergone multiple reviews.12 Qatar is noticeable in its absence. A PEFA analysis would help to benchmark where Qatar stands against other countries, both within MENA and globally. More importantly, it would provide Qatari policymakers with a framework on which to structure a reform agenda that builds on the country’s strengths and helps to address any problems and deficiencies, particularly with regard to procedures for strengthening budget predictability and ensuring the proper maintenance of capital assets.

Improving Service Delivery

The second priority area emphasized by the prime minister, service delivery, is one where Qatar is already doing relatively well along several dimensions. Qatar’s basic health and education statistics, for example, compare favorably with regional peers and global averages, although they lag results for other high-income countries.13 On the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index—a composite score that looks at trade-related topics ranging from customs clearance to the quality of infrastructure—Qatar posts a global rank of 34 that places it well below the UAE (7) but ahead of other countries in the GCC and broader MENA region.14 The Legatum Institute ranks Qatar first in the region in security and economic quality; third in terms of governance and creating favorable conditions for enterprises to start and expand; and fourth in terms of infrastructure and market access.15 The Bertelsmann Transformation Index ranks the quality of Qatar’s governance as “good” using a composite index focusing on criteria such as steering capability and consensus-building but also factoring in dimensions such as prioritization, implementation, and policy coordination.16

To enhance service delivery, the government has taken some promising steps forward recently with the creation of the Center of Excellence (CoE) under the Civil Services and Government Development Bureau.17 Consistent with emerging global best practices, the CoE seeks to eliminate fragmented legacy systems and make it easier for citizens to access services by uniting procedures for approximately 40 public agencies on a centralized platform. This should significantly improve the speed, quality, and access to government services and boost Qatar’s international e-government rankings. It will be important to use this opportunity to streamline and re-engineer agency business processes to eliminate unnecessary steps and requirements, as well as to monitor outcomes and troubleshoot workflow delays. Further steps to enhance data sharing between ministries and agencies would also facilitate progress.

Similar gains in improving government effectiveness and service delivery may be achieved through establishing a center of government (CoG) delivery unit under the Office of the Prime Minister. Global experience with delivery units has been mixed, but under certain conditions, they can be highly effective in helping leaders to tackle critical cross-cutting priorities. For Qatar, this will be particularly important as the Third National Development Strategy (NDS-3) moves into implementation. It would also be wise to study how the country was able to effectively coordinate its response to the COVID-19 pandemic across ministries to identify lessons regarding government effectiveness and coordination that could be applied to other areas.

Civil Service Reform

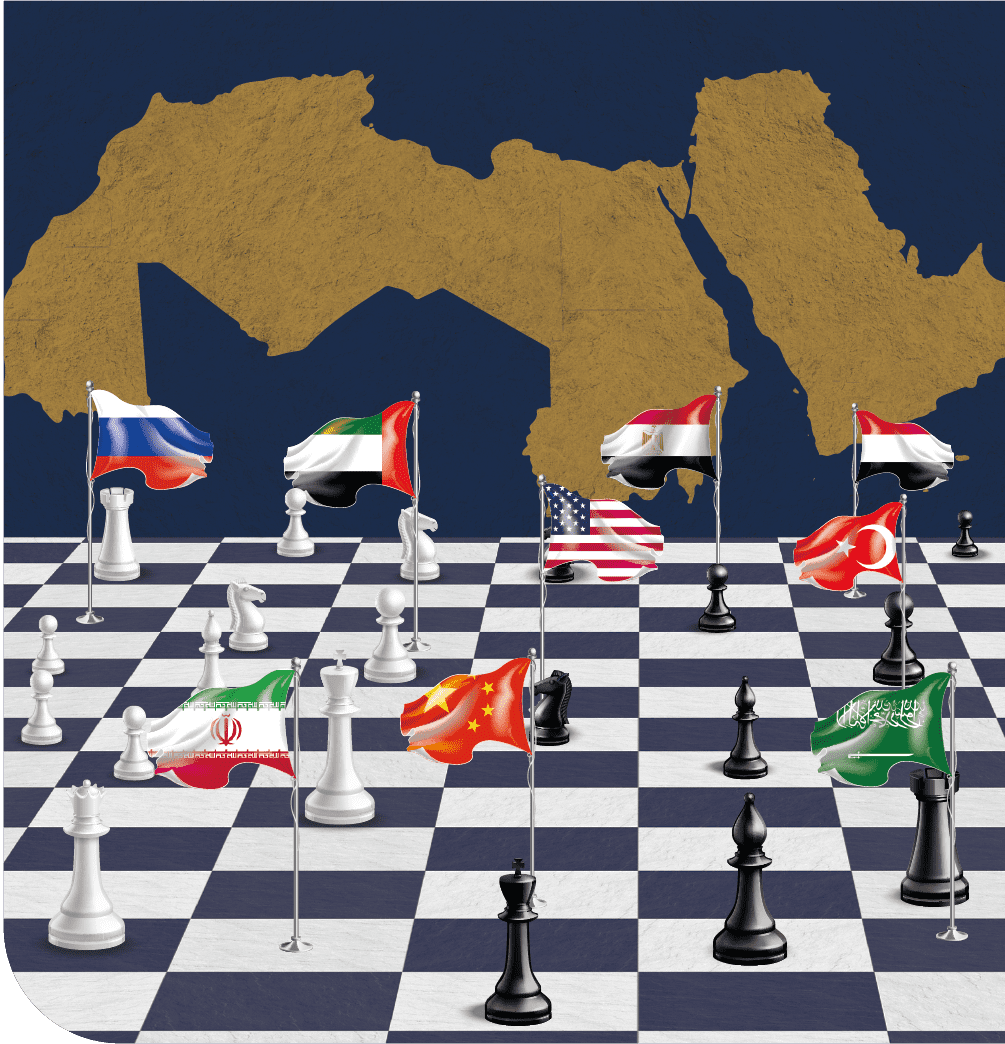

Prime Minister Al Thani underscored the need to diversify employment of nationals away from the public sector, where currently around 83% of working Qatari nationals are employed.18 Many GCC countries have sought to pursue this objective, with mixed success (See Figure 1). Bahrain and Oman are the furthest ahead, reflective of relatively low per capita national resource revenues. Saudi Arabia has made the most progress in recent years. Over the past decade, Saudi authorities have pushed aggressively to expand the employment of nationals through the Nitaqat program while encouraging more Saudi youth (particularly women) to take up private employment through a range of skills training and wage support programs. In turn, private sector employment among Saudi nationals has nearly doubled over the past decade.19 More recently, the Saudi public sector has begun to look seriously at term appointments and other means of moving away from a “job for life” mentality.

Qatar faces a significant challenge in this sphere. The Qatari public sector already employs a higher proportion of nationals than any other country in the GCC, and even unemployed Qataris have little interest in working in the private sector. In fact, according to the 2020 Labor Force Survey, only 12.5% of unemployed Qataris surveyed were interested in private sector work—and virtually no unemployed Qatari men were so inclined. Among the reasons given for avoiding the private sector, around a third cited hours of work and 17% referenced lower social status. But the majority—around 50% of the sample—cited lower wages as their principal disincentive. 20

Without tackling the challenge of pay disparity between the public and private sectors, Qatar will continue to face significant headwinds in the effort to diversify its labor force.

Figure 1: Share of Employed Nationals Working in the Private Sector, 2003-2022

Note: Due to gaps in the data, some years are estimated for Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia.

Source: Author calculations based on official labor market data from each country.21

This wage challenge, in turn, requires progress along several dimensions. It will be important to conduct a detailed labor market analysis to understand where the market distortions and pay discrepancies are most pronounced. A recent survey in another GCC country, for example, underscored that staff at the lower end of the pay scale were paid significantly more than their private sector counterparts with similar skills and education levels, whereas those at the high end were underpaid. In other words, that government was overpaying staff with relatively basic skills who brought limited added value, while struggling to attract and adequately compensate the talent required in high-priority areas, such as information technology or policy and financial analysis. A similar analysis in Qatar would allow the government to review its pay and employment policies and make appropriate corrections.

Secondly, establishing a wages and salaries commission would allow for the review of public salaries against inflation and their market comparators and facilitate annual recommendations for adjustments. This would serve to break the cycle of periodic, ad-hoc pay increases and allow the Qatari government to reign-in wage growth. Managed properly, such a commission could lead to significant downstream savings while helping the government to adjust salaries over time to better reflect market conditions.

Beyond these measures, a broader challenge that requires sustained attention involves improving the quality of human resource management within the public sector. Qatar invests relatively heavily in human capital development, spending more public resources on education per student than OECD countries.22 Yet it remains unclear whether the country can better maximize the return on this considerable investment, around three quarters of which flows directly into the public sector. Qatar should introduce a more strategic approach to workforce planning and talent management. Moreover, agency workforce plans would serve to better align strategic priorities and human resource requirements. Merit-based performance and recruitment processes, combined with carefully targeted training strategies, should complement these workforce plans.

Finally, ushering in these changes would require a comprehensive government strategy for civil service reform. To enhance accountability, priority components of this strategy should include introducing a one-year probation period for all new recruits; generating and circulating monthly statistics on absenteeism broken down by ministry, gender and grade to all ministries, agencies and departments; and publishing annual statistics on the number of employees sanctioned for malfeasance or non-performance.

Other Important Reforms in Performance Monitoring and Transparency

Beyond these priority areas, it would be advantageous for Qatar to upgrade its capacity to monitor government performance, track progress towards the realization of the Third National Development Strategy, and benchmark where the country stands against regional and global comparators—all areas where significant work is needed. The prime minister has called directly for improving efficiency and productivity, yet neither are currently being measured systematically within the government so it will be impossible to tell if progress is being made.

Linking these metrics with transparency—an area where, as noted above, the country lags well behind in global rankings—is of paramount importance. This would allow Qatari citizens, businesses, and investors to monitor progress towards NDS-3 targets and help ensure the responsiveness of government agencies. As the World Bank recently noted, transparency reforms can play an important role in facilitating the flow of information from within and outside the government, enhancing both responsiveness and accountability.23 They are also among the easiest reforms to implement. Qatar may wish to follow in the footsteps of Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia and join the Open Government Partnership. Drafting right to information legislation would further undergird this effort.

The government has recently taken some promising steps towards monitoring performance with the creation of the new Sharek (participate) online platform, which aims to facilitate access to digital services for citizens and help government agencies measure customer satisfaction. Tracking, monitoring, and regularly publishing the results from Sharek-based citizen satisfaction surveys, as well as routine cabinet-level discussion of these results, would help further improve accountability.

Conclusion

Qatari authorities will face significant challenges implementing reforms in the three priority areas raised by Prime Minister Al Thani. Fortunately, Qatar has access to the resources and talent necessary to realize this transition. The political will is present and the timing is also opportune. Qatar can build on the lessons learned from the country’s effective response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the successful organization of the 2022 FIFA World Cup. A world-class public administration system is the next great challenge confronting Qatar, the successful implementation of which will help ensure continuity in the country’s upward trajectory for decades to come.