The Turkish-Greek Rapprochement:

Time for European Engagement

Policy Note, February 2025

Introduction

In October 2024, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan declared that both he and Greek Prime Minister Kiriakos Mitsotakis backed efforts to resolve their long-standing political disputes. The Turkish president stated, “Both sides must be willing to define the problems, outline their content, and find solutions… in the context of our comprehensive approach to the Aegean Sea.”1 Just a month earlier, Greek Foreign Minister Giorgos Gerapetritis also highlighted the marked shift in Ankara-Athens relations, stating “our relationship now has improved significantly, and we have established some mutual sincerity in things.”2

Hakan Fidan, Gerapetritis’ Turkish counterpart, further affirmed that there remained grounds for optimism despite complex divergences complicating bilateral relations between Türkiye and Greece prior to his visit to Athens in late 2024.3 These statements indicate a positive trend; however, the durability of the ongoing Ankara-Athens rapprochement will largely rely on the European Union’s (EU) support. Against this backdrop, this policy note argues that a Greek-Turkish thaw needs to be couched within a broader Türkiye-EU reset, which should include extending regular invitations to Türkiye’s foreign minister to the EU’s Gymnich meetings (regular informal gatherings of the foreign ministers of EU member states) and establishing an increasingly structured foreign and security policy dialogue between both sides.

Bones of Contention

Greek-Turkish tensions have long been at the core of the multi-layered Eastern Mediterranean crisis, a highly contentious rivalry between Türkiye and a group of countries including Greece, Cyprus, Israel, and Egypt. The Turkish-Greek rivalry is underpinned by divergences over maritime boundaries, the respective parties’ approaches to the Cyprus question, energy, geopolitical files such as the Libyan conflict, and regional order at large.

Greece and Türkiye’s contestations have particularly centered on three principal dimensions.4 Firstly, disagreements on their maritime boundaries, including their continental shelves and exclusive economic zones (EEZ) in the Eastern Mediterranean. Secondly, both contest the extent of Greek territorial waters in the Aegean Sea. Thirdly, both are vigorously at odds over Cyprus, arguably the thorniest issue between Ankara and Athens.

Greece and Greek Cypriots affirm their support for a bi-zonal and bi-national federal framework, under a federal one-state solution. Conversely, Türkiye and Turkish Cypriots are inching towards a two-state solution. Beyond the aforementioned critical issues, Athens and Ankara also regularly disagree on the demilitarization of various Greek islands, and/or curbing irregular migration.

Traditional sources of friction in Greek-Turkish relations have been further exacerbated by several new regional dynamics, transforming bilateral tensions into a multilateral Eastern Mediterranean crisis. Chief amongst these factors were recent discoveries of hydrocarbon resources by Israel, Cyprus, and Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean, triggering Türkiye to embark on its own gas exploration5 and activating what had been a dormant dispute with Greece over maritime boundaries and EEZs.

Gas discoveries catalyzed the formation of the East Mediterranean Energy Forum and the proposed (but since shelved) EastMed gas pipeline project that would have transported gas from the Eastern Mediterranean, through cooperation between Israel, Cyprus, and Greece, to Europe.6 Türkiye’s exclusion from both projects prompted Ankara to view these initiatives as attempts to establish a regional energy and security order that marginalized its role. In response, Ankara adopted coercive diplomacy to undermine these initiatives, signing a deal with Libya’s Tripoli-based UN-recognized government in 2019, delimiting its maritime boundaries.7

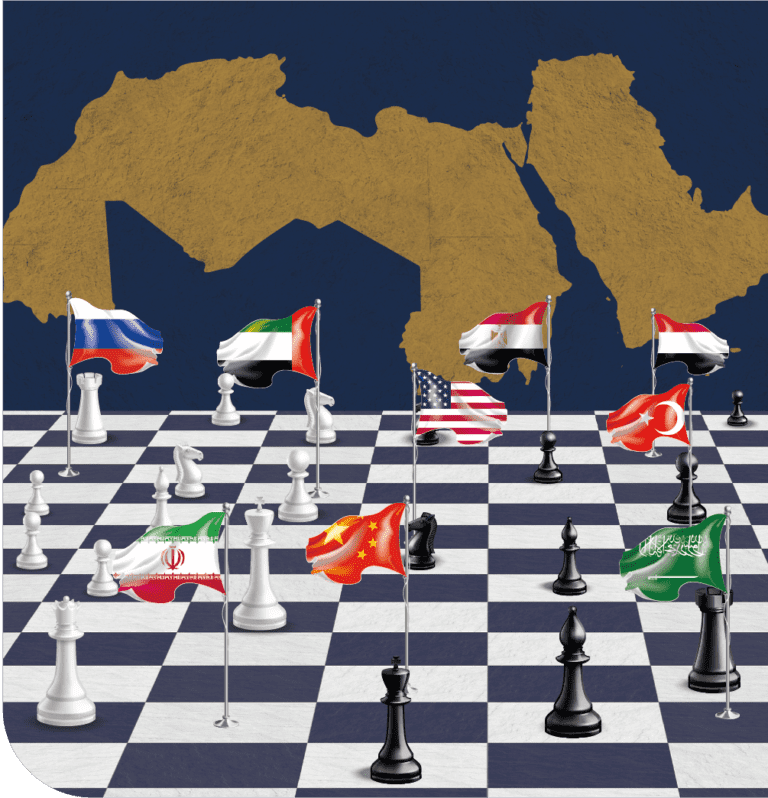

This deal conflicted with Greece’s view of its maritime boundaries, pushing Athens to sign a similar deal with Cairo in 20208 which in turn conflicted with Türkiye’s view of its maritime borders. These contestations reflect the nature of the Eastern Mediterranean crisis with multi-layered and interconnected sets of challenges on both the bilateral and multilateral levels. The political and geopolitical rupture between Türkiye and a number of Arab states, including Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, over opposing approaches to the Arab uprisings, which drove the aforementioned Arab states closer to Greece and Cyprus, further complicated these dynamics.9

An Evolving Context

Today, notwithstanding recent improvements in Greek-Turkish relations, the key disputes between both remain unresolved. That said, progress is possible, at least in reconciling conflicting maritime boundaries. Following a meeting on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly on September 25, 2024, Mitsotakis and Erdoğan instructed their foreign ministers “to explore whether conditions are favorable to initiate discussions on the demarcation of the continental shelf and exclusive economic zone.”10 Both ministers are also leading preparations for a high-level meeting between Greece and Türkiye in Ankara in January 2025.11 Although prospects for a breakthrough may be slim, it is nevertheless possible.

With other issues, such as disputed territorial waters in the Aegean Sea and the question of demilitarization and ownership claims over certain islands and isles, the prospect for progress is limited. The issues’ entanglement with each side’s view of its respective sovereignty makes them inherently less susceptible to compromise. However, efforts to tackle the Cyprus question have witnessed some global momentum recently.

In early 2024, UN Secretary-General António Guterres announced the appointment of former Colombian Foreign Minister María Angela Holguín Cuéllar as his Personal Envoy on Cyprus, with the hope of resuming talks suspended since 2017.12Despite this, the Greek and Turkish visions for addressing the Cyprus issue are fast diverging. For the Greek and Greek Cypriot sides, negotiations should aim to reach a solution within the overarching framework of a bi-zonal, bi-communal but unified, federal state. The Turkish and Turkish Cypriot side, on the other hand, is effectively inching towards a two-state solution on the island. While the positive climate in Greek-Turkish ties might provide some momentum for diplomacy over Cyprus, this is unlikely to lead to a resolution in the near future given the considerable gap in both positions. It is notable that the recent normalization between Türkiye and Greece has been bilateral, rather than a trilateral reconciliation involving Cyprus—an implicit recognition of the difficulty of progress on Cyprus.

Despite limited prospects for progress on core bilateral issues, regional dynamics are significantly changing. Israel’s wars on Gaza and Lebanon have hampered the Arab-Israeli-Greek cooperation that underpinned the Eastern Mediterranean Energy Forum, the EastMed pipeline project, and different variants of efforts to establish a regional energy or security order. Non-cooperation with Israel is arguably, currently, a common denominator across Arab policies. Prior to October 7, 2023, however, Egypt, Jordan, and the UAE were involved in a cooperative regional framework in the Eastern Mediterranean, alongside Israel, Greece, and Cyprus, with EU and U.S. support. In contrast, Türkiye had tense relations with Greece, Cyprus, Israel, Egypt, and the UAE.

This picture has drastically changed. Today, Türkiye has mended its ties with the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s visit to Ankara, on September 4, 2024, demonstrated the warming of Ankara-Cairo relations after a decade of estrangement13 whereas Israel’s relations are deteriorating with Türkiye and many Arab states. Israel’s wars on Gaza and Lebanon, and prospects of a war between Israel and Iran therefore make Arab-Israeli cooperation likely unfeasible in the foreseeable future.

Conclusion

To maintain stability in the Türkiye, Greece, Egypt, and Cyprus nexus and sustain the fragile thaw in Turkish-Greek ties, European support will be essential.

The Turkish–Greek rapprochement process should first be situated within a broader improvement in Türkiye’s relations with the West, particularly the EU. When Ankara and Athens’ relationship experienced a honeymoon in the late 1990s and early 2000s, it was shaped by relatively strengthened Türkiye-EU ties. Given the importance of the Eastern Mediterranean’s stability for Europe and its neighborhood’s security, the EU’s support for Turkish-Greek reconciliation efforts through incentives and engagement strategies is imperative.

Despite the currently favorable climate in bilateral relations, core disputes remain volatile and highly politically sensitive. Accommodations and concessions on these issues are inherently difficult and politically challenging. The current nascent reconciliation characterizing Türkiye-Greece relations could therefore easily relapse into political deadlock. To prevent this, the EU should adopt an active policy of supporting Greek-Turkish talks, capitalizing on the current, relatively positive bilateral climate.

Notably, Ankara-EU ties have also been warming. Türkiye removed its veto over Sweden and Finland’s NATO membership bid in early 2024 and early 2023 respectively.14 A month later, Germany, the only member of a four-nation Eurofighter project that previously opposed selling the jets to Türkiye, lifted its objections.15 The Greek-Turkish thaw should therefore be couched within this broader Türkiye-EU reset. Donald Trump’s re-election as president of the United States might also provide an additional impetus for Türkiye and the EU to explore new avenues for cooperation and align their visions on European security, including in the Eastern Mediterranean. To further boost this reconciliation, the EU should regularly invite the Turkish foreign minister to the Gymnich meetings. Fidan’s invitation to a Gymnich meeting in August of 2024 was a step in that direction,16 but these invitations should be extended routinely.

Finally, the EU should launch a structured foreign and security policy dialogue with Türkiye.17 This would not only buttress the thaw in Greek-Turkish relations but could also help Ankara and Brussels coordinate and communicate their policies in a more effective manner. The future of Türkiye-Greece and Türkiye-EU relations will therefore rest on the choice to either cooperate or compete in a shared neighborhood.

Endnotes

1 “President Erdoğan answers journalists’ questions on his return from visits to Albania and Serbia,” Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye, October 12, 2024, https://www.iletisim.gov.tr/english/haberler/detay/president-Erdoğan-answers-journalists-questions-on-his-return-from-visits-to-albania-and-serbia.

2 “Greece says better ties with Türkiye could revive Cyprus talks,” Daily Sabah with Reuters, September 24, 2024, https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/diplomacy/greece-says-better-ties-with-turkiye-could-revive-cyprus-talks.

3 “Turkish foreign minister heads to Athens with positive agenda,” Daily Sabah with Agencies, November 7, 2024, https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/diplomacy/turkish-foreign-minister-heads-to-athens-with-positive-agenda.

4 Galip Dalay, Turkey, Europe, and the Eastern Mediterranean: Charting a Way Out of the Current Deadlock, Policy Paper, (Doha, Qatar: Brookings Doha Center, January 2021), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/Türkiye-europe-and-the-eastern-mediterranean-charting-a-way-out-of-the-current-deadlock/.

5 Ibid.

6 “EastMed pipeline project still viable, Edison CEO says,” Reuters, July 7, 2023,

https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/eastmed-pipeline-project-still-viable-edison-ceo-says-2023-07-07/.

7 Daren Butler and Tuvan Gumrucku, “Türkiye signs maritime boundaries deal with Libya amid exploration row,” Reuters, November 28, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/Türkiye-signs-maritime-boundaries-deal-with-libya-amid-exploration-row-idUSKBN1Y21VL/.

8 Nektaria Stamouli, “Greece signs maritime border deal with Egypt amid spat with Turkey,” Politico, August 6, 2020, https://www.politico.eu/article/greece-signs-maritime-border-deal-with-egypt-amid-spat-with-Türkiye/

9 Galip Dalay, Türkiye’s Middle East Reset: A Precursor for Re-Escalation?, Policy Paper, (Doha, Qatar: Middle East Council on Global Affairs, August 9, 2022), https://mecouncil.org/publication/Türkiyes-middle-east-reset-a-precursor-for-re-escalation/.

10 “Greece and Türkiye explore holding talks on maritime zones,” Reuters, September 25, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/greece-Türkiye-explore-holding-talks-maritime-zones-2024-09-25/

11 Ibid.

12 “Secretary-General Appoints María Angela Holguín Cuéllar of Colombia Personal Envoy on Cyprus,” UN Press, January 5, 2024, https://press.un.org/en/2024/sga2255.doc.htm.

13 “Egypt’s el-Sisi says Türkiye visit paves way for ‘new phase’ in relations,” AlJazeera, September 4, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/9/4/egypts-el-sisi-says-Türkiye-visit-paves-way-for-new-phase-in-relations.

14 George Wright, “Turkey parliament backs Sweden’s Nato membership,” BBC News, January 24, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-68076829; Ivana Kottasova, “Turkey approves Finland’s NATO application, clearing the last hurdle. Sweden is still waiting,” CNN, March 31, 2023, https://edition.cnn.com/2023/03/30/europe/turkey-vote-finland-nato-membership-intl/index.html.

15 “Germany says UK taking lead on possible Eurofighters for Türkiye,” AlJazeera, October 19, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/10/19/germany-says-uk-taking-lead-on-possible-eurofighters-for-Türkiye

16 Gokhan Celiker and Can Efesoy, “Türkiye invited to EU informal foreign ministers meeting in Brussels,” Anadolu Agency, August 22, 2024, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/turkiye-invited-to-eu-informal-foreign-ministers-meeting-in-brussels/3310306

17 Galip Dalay, Deciphering Türkiye’s Geopolitical Balancing and Anti-Westernism in Its Relations with Russia, SWP Comment, (Berlin, Germany: The German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), May 2022), https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2022C35/.