The Paradox of Trust in the Military

in the Middle East and North Africa

Issue Brief, August 2024

Key Takeaways

Trust in the military is surprisingly high in the Middle East and North Africa: Despite military involvement in coups, conflicts, political interference, and economic encroachment in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, the majority of surveyed citizens express high trust in the armed forces, significantly more than other national institutions.

Trust in the military reflects disillusionment with politics and the need for stability: Combined with people’s lack of confidence in parliaments and governments, the military’s high ratings signal a form of governance fatigue. At the same time, significant trust in the armed forces amongst those who feel safe indicates that the institution is envisioned as a stabilizing force.

Safety, ideological, and economic factors explain public trust in the military: In addition to personal safety, ideology plays an important role, with conservatives displaying high levels of trust and Islamists showing lower levels. Additionally, trusting political institutions and being part of lower economic classes positively impact trust in the military, though this varies depending on the regime type.

The military engenders trust among proponents of democracy: This surprising finding in civilian-led countries suggests that many do not see a contradiction between trusting the military and supporting democracy. This is consistent with growing support for a strong executive amongst citizens in the region in the face of deteriorating government effectiveness and socio-economic outcomes.

Introduction

The institution of the military is experiencing a resurgence around the globe. Citizens are placing higher levels of trust in the armed forces—even in regions with a history of military interference or domination. In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, where military elites hold a great deal of political and economic power, around 70% of surveyed citizens in 2021-2022 expressed significant trust in the armed forces.1 This surpasses the levels of trust accorded to elected officials, civil society, and the news media.

The military’s centrality to the politics and stability of this region was reaffirmed in the aftermath of the Arab uprisings and subsequent developments. Indeed, the military’s support for transition or the status quo dictated the trajectory of events in many countries.2 In Tunisia, the army leadership’s decision not to support President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali led to his ousting. At the same time, its adherence to civilian authority after 2011 facilitated a relatively smooth transition. In contrast, the Syrian army’s loyalty to President Bashar Assad’s regime fueled a brutal civil war that has lasted for over a decade, resulting in widespread devastation and humanitarian crises. As a result, MENA armies have been at the heart of policy debates and media scrutiny. This discourse has predominantly centered around the role of military elites in politics,3 and little attention has been paid to the public and the paradoxical high trust it places in this opaque institution.4

This issue brief analyzes public opinion data to explore military-society relations in the MENA region. It begins by examining the military’s role during modern times, focusing on patterns of political and economic interference. It then explores data on trust in the armed forces in nine countries across the MENA region and identifies the characteristics that make citizens more or less likely to trust them. Building on these findings, it provides insights into the broader dynamics of governance, stability, and public sentiment in the region.

Why Trust in the Military is Surprising

High trust in the military is especially surprising, considering that armies in the MENA region have a history of turning on governments, blocking transitions, repressing citizens, and encroaching on the economy. Dark, repressive episodes have marred the military’s reputation in the region, with soldiers frequently deployed to quell protests. For instance, during the 2011 uprisings and subsequent civil war in Syria, military forces committed human rights abuses, including extrajudicial killings and torture.5 In Sudan, following President Omar al-Bashir’s removal in 2019, soldiers were deployed to disperse pro-democracy demonstrators, resulting in violence, injuries, and fatalities.6 In Iraq, soldiers brutally suppressed protesters during the Shia and Kurdish uprisings in 1991, which led to widespread casualties and displacement.7

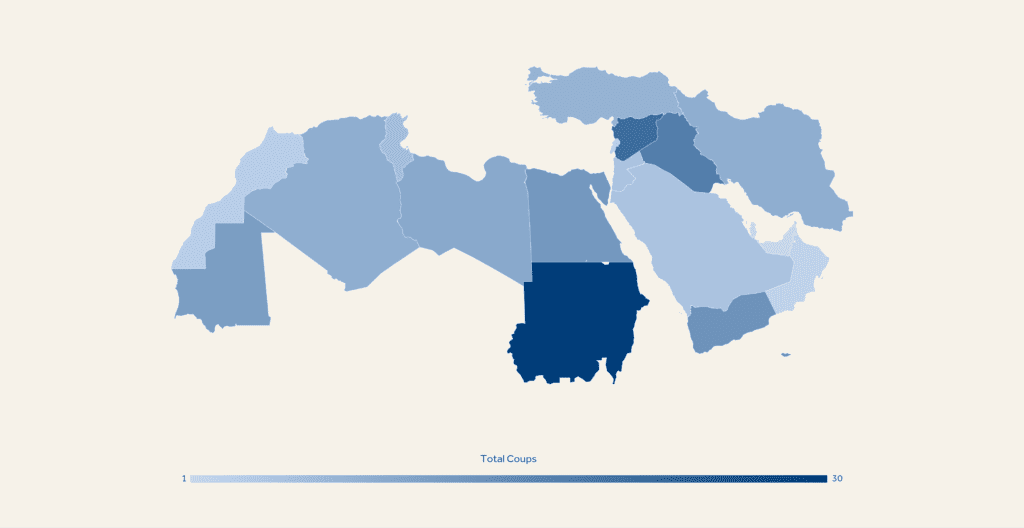

It is not just citizens who are at risk but governments as well. Military factions in nearly every MENA country have staged at least one coup since 1945 (see figure 1).8 These events destabilized governments and undermined efforts to establish democratic governance in the region. Some coups occurred shortly after countries gained independence, leading to the establishment of military regimes that ruled for decades. Notable examples include the 1952 overthrow of the Egyptian monarchy by the Free Officers Movement, the 1963 coup by the Ba’ath party in Syria, and the 1969 al-Fateh Revolution led by Muammar Gadhafi in Libya.9

Other coups reversed democratic rule, as seen in Sudan in 1969 and 1989.10 These events halted democratic progress and perpetuated a cycle of authoritarianism and instability in the country, which persists to this day. Even failed coups in the MENA region have had significant repercussions. For instance, two failed coups in Morocco in the early 1970s precipitated the most repressive decades of King Hassan II’s rule,11 while several attempted coups against Gadhafi in 1975 led to a decades-long strategy to marginalize the army.12

Figure 1: Coups and Coup Attempts in the Middle East and North Africa (1945-2022)

Note: Figure 1 shows the frequency of attempted, conspired, and successful coups in the Middle East and North Africa from 1945 to 2022. It excludes events orchestrated by foreign powers.

Source: This map was constructed by the authors using data from the Cline Center, “Coup d’État Project.” 13

Military leaders have also frequently intervened in politics by obstructing political processes and supporting contested regimes. In Sudan, military leaders blocked a political transition in 2021, which led to civil war and continual armed conflict.14 Similarly, the Algerian army leadership stopped a years-long revolution in its tracks in 2019 and backed Abdelmadjid Tebboune’s presidency.15 Decades earlier, the military annulled free elections that were poised to bring an Islamist party to power, sparking a decade-long civil war.16 In Egypt, army leaders took over in 2013 after ousting the country’s first democratically-elected president and remain in power today.17

Outside the realm of politics, military elites have reportedly enabled and benefited from corruption and cronyism in various countries.18 In Egypt, for example, the military has established a significant economic empire spanning sectors such as construction, manufacturing, agriculture, and consumer goods.19 This economic influence is facilitated through an extensive network of companies and enterprises that enjoy preferential treatment and government contracts, granting them a competitive advantage over private businesses. Algerian military elites benefit from the country’s rentier economy by negotiating with political and administrative figures. As a result, they receive preferential treatment in real estate ventures, tax liability, and bureaucratic procedures. Additionally, military actors are reported to profit from smuggling operations in border areas, particularly where law enforcement agencies lack access.20

Economic interference by military actors can have catastrophic repercussions. In post-2014 Libya, powerful militias, armed groups, and military factions have competed over control of state resources, including oil infrastructure, border crossings, and smuggling routes.21 This militarization of the economy has resulted in intensified resource competition, rent-seeking behavior, and the exploitation of Libya’s natural resources for financial gain. Consequently, economic instability has been exacerbated, efforts to revive the economy have been hindered, and the country has been plunged into political turmoil.

How High is Trust in the Military in the Middle East and North Africa?

Despite the tumultuous history of military involvement in the MENA region, recent survey data conducted by the Arab Barometer in 2021–2022 reveal that the military commands significant trust among citizens. Indeed, more than 70% of surveyed citizens express significant trust in the armed forces. This has remained consistent over the years. Between 2011 and 2022, levels of moderate and high public trust in the military in MENA varied on average between 71% and 81% (see figure 2).

Source: This figure was constructed by the authors using data from the Arab Barometer Waves II, III, IV, V, and VII.22

Note: Some countries were present in certain waves but not others.

Levels of trust in the armed forces do vary across countries. On average, between 2011 and 2022, they ranged from 92% in Tunisia to 47% in Libya (see Figure 3). Yet, even in Libya, a significant portion of the population expressed high trust in the armed forces. For example, in the eastern part of the country, 87% of surveyed citizens indicated the army could be trusted a great deal or quite a lot in 2019 (versus 60% in the south and close to 57% in the west).23 Furthermore, in all surveyed MENA countries, including Libya, the armed forces are accorded significantly more trust than most national institutions like government, parliament, and civil society (see Figure 4).24 In fact, when comparing trust in the armed forces to trust in the next most trusted institution—in this case, it is civil society in most countries, except for Egypt—the difference in favor of the armed forces ranges from 61 percentage points in Lebanon to 19 percentage points in Sudan.

Source: This figure was constructed by the authors using data from the Arab Barometer Waves II, III, IV, V, and VII.25

Source: This figure was constructed by the authors using data from the Arab Barometer, Wave V.26

The Public Equation: Who Trusts the Military and Why?

What explains the high levels of trust that MENA citizens place in the armed forces?27 Our research has identified several factors that should influence MENA citizens likelihood of trusting their armed forces based on studies of civil-military relations and institutional trust and the growing political economy literature on the role of militaries in the MENA region.28 These include personal safety, economic class, political conservatism, Islamist orientation, trust in institutions, and attitudes toward democracy.29

We empirically examined these factors using data from the Arab Barometer Wave V survey, collected between 2018 and 2019, at a time when protests took place across the region, and consequently, armies were deployed to varying degrees across countries.30 The data comprises some 10,000 responses from nationally representative samples across nine countries. Four of these countries have civilian-led governments (Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, and Tunisia), and five have an extended history of military intervention or rule (Egypt, Iraq, Libya, Sudan, and Yemen).31 This allows us to examine whether the drivers of trust in the armed forces vary under military versus civilian rule.

What makes people more likely to trust the military? Personal safety emerges as a key driver. Individuals who feel their personal and family’s safety is ensured are much more likely to trust the military. This suggests that the public may perceive the military as a bastion of stability and order that can be called upon in times of upheaval. In countries like Jordan or Morocco, where robust safety measures are in place, people may attribute this success to the military’s role in maintaining security. In less stable countries like Libya or Sudan, where military actions have contributed to chaos, the institution is viewed nonetheless as a safeguard against insecurity and a defender of a fragile state.

Ideology also plays a role. Conservatives—those who defer to the state regardless of their own political views—tend to trust the military more than others, perhaps because they view the military as a symbol of traditionalism. Similarly, despite its controversial history, the military garners trust among proponents of democracy, challenging conventional assumptions about its compatibility with democratic governance.32 Dividing the data by regime type introduces an interesting caveat: data from countries with civilian-led regimes is driving the positive relationship between support for democracy and trust in the military. In countries with a history of military intervention or rule, we find some evidence of the opposite result: proponents of democracy tend to trust the military less, reflecting perhaps the erosion of democratic practices under extended military rule.

Trust in political institutions—measured by views on governments or parliaments—also positively impacts trust in the military. Overall, those who trust political institutions are more likely to trust the armed forces. However, when we take regime type into account, we see a change. Specifically, individuals in civilian-led regimes who trust political institutions less are more likely to trust the military. This could be because, in settings where citizens perceive political institutions in a negative light, they view the military as a symbol of effective performance by comparison. This explains the strikingly high levels of trust in the military in countries like Jordan, Tunisia, and Lebanon (Figure 3) and the significant difference in levels of trust in the military and in the various political institutions in these countries (Figure 4). On the other hand, in countries with a history of military intervention or rule, trust in political institutions goes hand-in-hand with trust in the military. This could be because the military interferes in the political sphere and is perceived as close to or in control of political institutions.

Interestingly, individuals in higher income brackets are less likely to trust the military. The well-to-do may fear the encroachment of the military on the economy, as in countries like Algeria and Egypt, where military elites dominate certain sectors or take advantage of ties to the ruling party to receive preferential treatment at the expense of the private sector. Contrastingly, trust among the lower economic classes may stem from the role of the armed forces as large employers,33 especially in military-led countries, and the high representation of these classes in their ranks.

Finally, an Islamist orientation—measured by people’s views on the role of clerics in politics or the role of Sharia in legal systems—predicts less trust in the military. This finding aligns with the expectation that Islamist supporters would harbor mistrust toward the military due to its role in repressing Islamists in many MENA countries, for example, from Egypt in 2013 to Algeria in 1992 and Syria in 1982.34

Overall, our findings paint a general picture of the drivers of heightened trust in MENA’s armed forces. The military draws support from conservative, non-Islamist, and lower economic segments of the public, who have lost confidence in parliaments and governments and believe the institution is a bulwark against insecurity and instability. Combined with declining confidence in democracy as the best system of rule and readiness to empower a strong executive, the high trust in the military highlights broader governance fatigue and disillusionment with the political system.35

The Future of Military-Society Relations

Decades of political interference, economic mismanagement, blocked transitions, and coups by the military have profoundly affected MENA countries. Yet, even in the throes of political turmoil and social discord, the military retains its favorable standing among the public in most countries, especially with citizens who care about safety, are politically conservative, and, interestingly, support democracy. What does this tell us about the region’s broader social and political landscapes?

High trust in the military has palpable societal implications and serves as a litmus test for public sentiment. It reflects public disillusionment with political actors and institutions, signaling a form of governance fatigue. Simultaneously, the military is envisioned sentiment that seeks an anchor in times of socio-economic and political upheaval. Therefore, high trust in the military is both an indicator of institutional failure and a testament to the enduring need for stability.

This phenomenon is thus symptomatic of broader trends—disenchantment with political processes, the fraying of social contracts, and a yearning for stability. These trends shape policy directions, influence political outcomes, and contribute to defining national identities. In essence, the question of military trust is intertwined with the future trajectory of democratic norms and institutions, both within the MENA region and beyond.

Crucially, high trust in the military is not unique to the MENA region but reflects a global trend.36 Across democracies and dictatorships, in both affluent and struggling economies, armed forces outrank other national institutions. This trend holds even in nations with historically violent armies.

In Africa, home to the highest number of coup d’états in modern history, six successful coups have taken place since 2020, and fighting is ongoing between armed factions in Sudan and Mali.37 Approximately 62% of Africans, on average, expressed significant trust in their armed forces in 2022.38 Latin American and Caribbean militaries historically led repressive regimes and interfered in political processes. Now, the military is wading back into politics, often at the behest of civilian leaders. There, the armed forces inspired trust in 54% of surveyed citizens in 2023, more trust than any other national institution.39

How can we leverage insights from the Middle East and North Africa to inform strategies for strengthening democratic norms and improving military-society relations in other regions? The trust that many place in the military raises questions about what citizens seek from state institutions. Unlike political institutions, the military is a resilient entity in the public’s perception, seemingly entrusted with the formidable task of delivering security and defending stability. What does this mean for the future of military-society relations in these regions? Persistently high trust may signal a shift in political culture, where the military’s role in society goes beyond security provision.

While armies in these regions have been active agents in upending or sustaining political orders, the trust they enjoy from citizens points to broader social dynamics. Despite the military’s complex and often troubling role in governance, it commands a level of public trust that challenges conventional wisdom and compels us to reassess our understanding of contemporary military-society relations. This could be a bellwether for future governance models and societal expectations and may point to a need for political actors to consider the military’s place in democratic governance more seriously, perhaps increasing civilian oversight mechanisms.

For now, as the crisis in Sudan unfolds, and the juntas that recently seized power in Sahel countries continue to rule, all eyes are on the military—a vivid reminder of its enduring influence and its role as both a stabilizing force and a potential catalyst for change.40