Tax Reform in Saudi Arabia:

Assessing the Economic and Societal Impacts

Issue Brief, May 2024

Key Takeaways

Profound Economic Hurdles after the 2014 Energy Crisis: Despite prior robust growth of the Saudi economy, fueled by the energy sector, a sharp decline in oil prices, exacerbated by factors such as the United States (U.S.) shale oil boom, heightened spending, and the global pandemic, led to significant fiscal imbalances.

Immediate Positive Impact of VAT Implementation: The value-added tax (VAT) allowed the kingdom to diversify revenue sources and stabilize government finances. Despite initial inflationary pressures, VAT contributed to improved non-oil revenue growth, fiscal deficit reduction, and economic recovery following the oil crisis.

Knowledge is Crucial for Public Acceptance of VAT: Survey data suggest that the relatively subdued public response to VAT implementation in Saudi Arabia highlights the public’s understanding of fiscal reform imperatives. It further underscores the importance of transparency and communication in fostering societal acceptance of taxation policies.

VAT Fiscal Reform Lessons for the Other Gulf States: Saudi Arabia’s VAT experience emphasizes the need for tailored approaches that consider socio-economic diversity, public perceptions, and distributional impacts when implementing similar fiscal reforms.

Introduction

As fossil fuel reserves run low and populations continue to grow, resource-wealthy countries face fiscal constraints that push them to shift away from the traditional no-taxation model. As one of the world’s largest oil exporters, Saudi Arabia is a case in point. Facing significant economic hurdles brought about by recent oil price fluctuations and the global pandemic, the Saudi regime has sought to reduce public spending, raise revenue, and move away from its economic dependence on natural resources.

In 2016, along with other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, Saudi Arabia agreed to impose a value-added tax (VAT), a fiscal policy long recommended by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).1 VAT is an indirect tax on the final consumption of goods and services. It is levied on the value of imports and the added value of goods and services at each stage of the manufacturing and marketing process.2

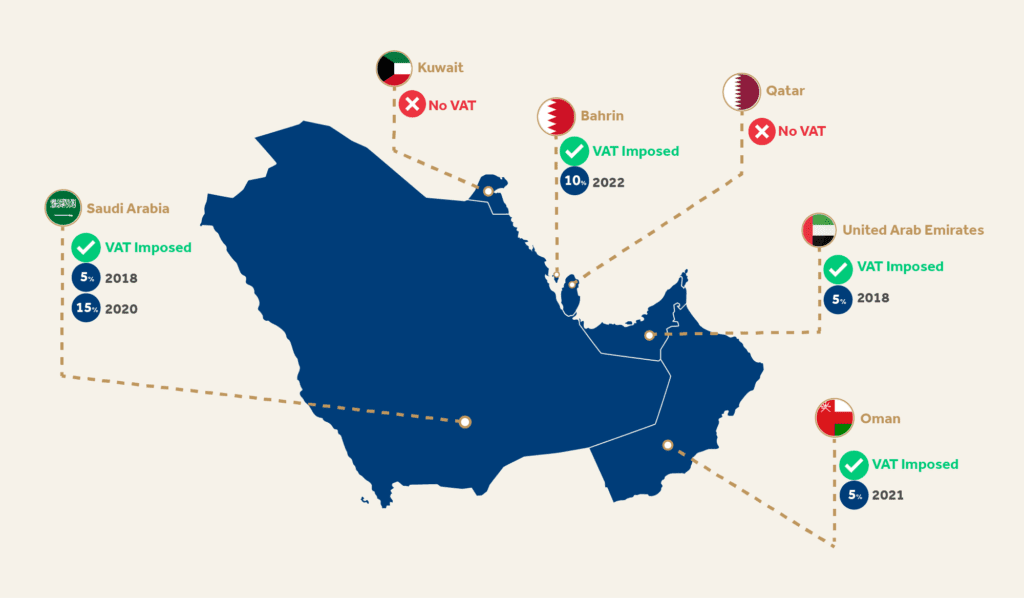

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates imposed VAT in 2018, followed by Oman in 2021 and Bahrain in 2022, as shown in figure 1. While VAT has had a positive impact on Saudi finances, questions remain regarding its societal implications, particularly in light of its regressive nature.3 Introducing any tax in the GCC alters the social contract between governments and citizens, traditionally defined by the absence of taxation and, consequently, limited demands for representation or accountability from the regime.4 Saudi Arabia has operated as a rentier state since the 1970s oil boom. While taxes on personal income and capital gains were introduced at one point, they excluded Saudi citizens. Younger generations, especially, have lived in a tax-free environment their whole lives. This raised questions about how Saudi citizens would react to the imposition of an indirect tax, especially when the regime increased spending on megaprojects.5

Figure 1: Value-Added Tax Implementation in the Gulf Cooperation Council States

Source: This map was constructed by the authors using information from PwC’s Worldwide Tax Summaries Online.6

Little research exists on the impact of VAT imposition in Saudi Arabia. This Issue Brief addresses this gap by examining the root economic challenges that led to tax reform in the kingdom and by exploring the economic and societal impact of this policy. Building on this analysis, it draws lessons for other Gulf monarchies.

The Pre-Tax Economy

Saudi Arabia has had a rentier economy for most of its modern history. Until 2018, the state derived a significant portion of its national revenues from oil rents and taxing citizens was unnecessary. As a result, the country’s economy was largely dependent on energy markets.

Energy markets boomed in the early 2000s, stimulated by growing oil demand from Emerging Market and Development Economies (EMDEs).7 In the decade leading up to the 2014 energy crisis, Saudi Arabia witnessed substantial economic expansion driven by favorable conditions in the energy sector. The surge in oil prices brought about significant external and fiscal surpluses that boosted public spending and stimulated private sector activity, contributing to an impressive real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth of 11 % in 2011.8

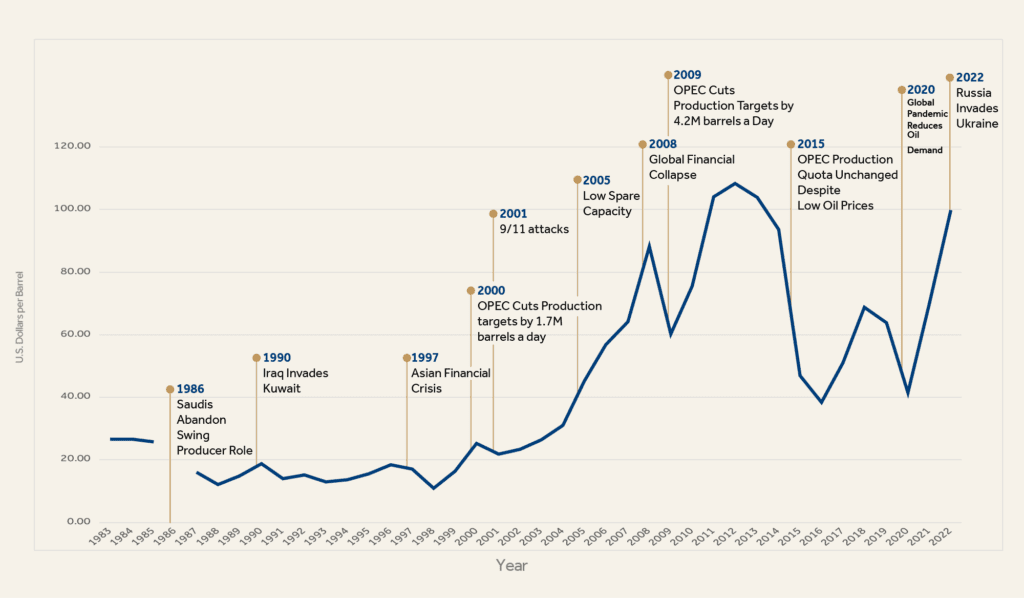

However, in 2014, as depicted in figure 2, oil prices declined significantly and persistently, representing one of the most substantial drops since World War II.9 The prices plummeted by approximately 70% between mid-2014 and early 2016 to below $30/barrel in January 2016.10 This price plunge was caused by a combination of factors, notably the United States shale oil boom, an overestimated geopolitical risk, the failure of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) policies, and shifts in global oil demand. The Saudi state’s high public spending further exacerbated the economic situation.

Figure 2: Selected crude oil prices – Saudi Arabia (1983-2022)

Source: This figure was constructed by the authors using data from OPEC and information from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.11

Low Oil Prices

Supply disruptions in several oil exporters in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region—notably the conflict in Libya, sanctions on Iran, and supply concerns in Iraq—initially eclipsed the increase in U.S. shale oil production, which was expected to merely cover the disruptions.12 Nevertheless, production picked up quickly, and U.S. shale oil became a major driver of the 2014 oil glut and the ensuing price decline in the second half of 2014.13

The price drop, triggered by supply dynamics, was further aggravated by low demand. Lower energy prices were anticipated to stimulate economic activity, yet global economic growth decelerated. Stalling economic recoveries following the financial crisis and diminishing growth prospects in EMDEs and major oil importers dampened demand for oil.14

The magnitude and persistence of the price depreciation were exacerbated by OPEC’s unprecedented decision not to adjust output levels to stabilize prices.15 Key producers like Saudi Arabia hoped their lower production costs would force other producers to cut output.16 However, technological advancements boosted shale oil’s resilience to lower prices by stimulating efficiency and production cost gains.17

High Expenditure

In 2014, the IMF stressed that while Saudi Arabia possessed sound fiscal buffers and major deposits at the Central Bank (Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency), its fiscal policy and spending trajectory risked depleting these buffers and leaving the country vulnerable to oil price shocks.18

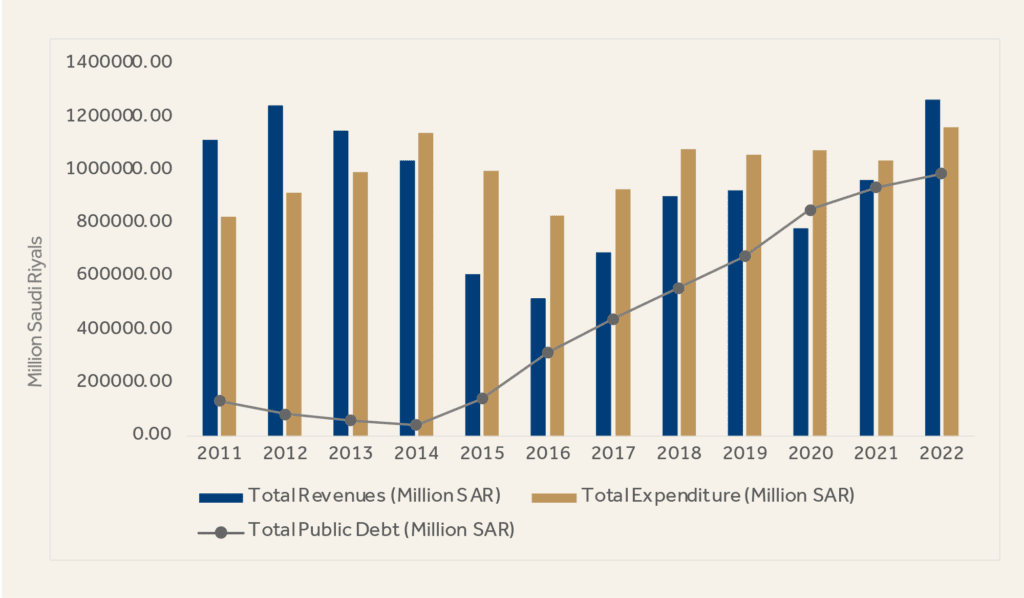

Saudi Arabia’s expenditure trajectory was indeed exerting pressure on the fiscal balance well before the oil price plunge (see figure 3), with the surplus dropping from approximately 12% of GDP in 2012 to 5.8% in 2013.19 The country had already embarked on several “ambitious” fiscal programs to fund large-scale initiatives like the Mecca and Medina expansions.20 Another noteworthy expenditure that further exacerbated Saudi Arabia’s economic strain was military expenditure exceeding 330 billion riyals (about $87 billion) in 2015 following its military intervention in Yemen.21

Figure 3: Total Revenue vs. Total Expenditure vs. Total Public Debt – Saudi Arabia (2011-2018)

Source: This figure was constructed by the authors using data from the Saudi Central Portal for Open Data.22

In addition to the fiscal constraints, Saudi decision-makers were grappling with a variety of socio-economic challenges. The country’s growing and increasingly young and educated population was exerting pressure for job creation and affordable housing. The Saudi labor force has been experiencing steady growth since the early 2000s, and youth unemployment rates for Saudi nationals aged 15-24 reached a record 46% in the third quarter of 2017.23 Such a burgeoning labor force exacerbated urbanization and paved the way for a housing shortage, ignited mainly by the lack of affordable housing, especially for the youth and the less well-off.24 To counter this, the state funded major real estate and housing initiatives, including one launched by King Abdullah in 2011 and the Sakani Program initiated in 2018.25

Failed Stabilization Efforts

Accordingly, the drop in oil prices and the subsequent decline in oil revenues—from 32.3% of GDP in 2014 to 18.4% in 2015—coincided with a 14.7% surge in government expenditures during 2014.26 This further strained the fiscal balance, which moved into a deficit of approximately 3.4% of GDP in 2014.27 Afterward, despite government efforts to consolidate and cut public spending, the fiscal deficit continued to widen, reaching 15.4% of GDP in 2015.28

Eventually, the resistance of shale oil production to lower price levels and fiscal pressures in exporting countries led to the OPEC+ deal of 2016, in which OPEC members and several non-OPEC producers, notably Russia, agreed to cut production levels.29 Consequently, Saudi Arabia committed to lowering its production by 486 thousand barrels/day (to 10,058 thousand barrels/day).30 This led to a modest stabilization of prices in 2017, bouncing back to around $60/barrel at the end of the year.31 The recovery of oil prices reflected positively on the fiscal deficit, which started contracting to around 9% of GDP in 2017.32 Despite improvement in the fiscal position, public debt was soaring, as illustrated in figure 3. The decline of oil GDP, as per the OPEC+ agreement output cuts, pushed real GDP growth to 0.9%.33

VAT Implementation in Saudi Arabia

Saudi decision-makers sought to diversify fiscal revenue sources to address these protracted economic issues, control fiscal deficits, and reduce the impact of oil price fluctuations. To that end, they undertook IMF-recommended fiscal reforms, including slashing subsidies and imposing VAT. While momentous, this was not the first time the government had levied taxes in the kingdom. Saudi Arabia already had several tax policies in place, including Zakat, a corporate income tax applicable to non-Saudis, a social insurance tax enforced on Saudi nationals, withholding tax, and the White Land Tax imposed on vacant land.34

In response to mounting fiscal challenges, the Saudi government imposed further taxes between 2017 and 2018. Expat levies were introduced in 2017, targeting dependent residents and companies hiring foreigners.35 An excise tax was also enforced in 2018 on specific commodities, notably tobacco at a 100% rate, soft drinks at a 50% rate, and energy drinks at a 100% rate.36

In January 2017, Saudi Arabia ratified the GCC Value Added Tax Agreement by royal decree and implemented it one year later.37 Initially, in 2018, the General Authority of Zakat and Tax set the rate at 5% for most goods and services in accordance with the agreement. Against IMF advice, the rate was later increased to 15 % in 2020. Certain businesses have been exempted from registering depending on their taxable annual turnover. As of December 2018, the threshold for mandatory registration has been set at 375,000 riyals, and the threshold for voluntary registration at 187,500 riyals.38

Not all goods and services in Saudi Arabia are subject to this rate. Some are zero-rated, including medicines and medical equipment, exports outside the GCC region, services supplied to non-GCC residents, international transportation of goods and people, and metals for investments. Islamic finance products, insurance, money transfers, financial services, 39 and residential real estate leases are exempt.

The government introduced compensatory measures to absorb the negative impact of the fiscal reform. In 2018, it committed to paying VAT for citizens benefiting from private health and educational services and those purchasing first-time residences.40 As per royal decree, the state would bear VAT on tuition fees and textbooks for Saudis enrolled in private educational institutions accredited by the Ministry of Education, in addition to VAT on cash payments on taxable health services and out-of-pocket payments incurred by insured citizens.41 The state further committed to paying VAT on first residences valued at no more than 850,000 riyals.42

It further introduced several stimulus initiatives, mainly cost-of-living allowances for public employees and the Citizen Account Program.43 This initiative aimed to compensate eligible households for purchasing power losses due to fiscal reforms, with the allowance varying based on household income and size.44

VAT’s Impact on the Economy

VAT has catalyzed a notable surge in non-oil revenue generation, especially in the wake of the oil crisis. However, despite these revenue gains, escalating government spending and external economic shocks hindered fiscal stability, underscoring the need for prudent fiscal management strategies. While the introduction of VAT was associated with heightened inflationary pressures, compensatory measures introduced by the state proved effective in smoothing the impact on consumption levels.

Impact on Revenue Generation and the Fiscal Position

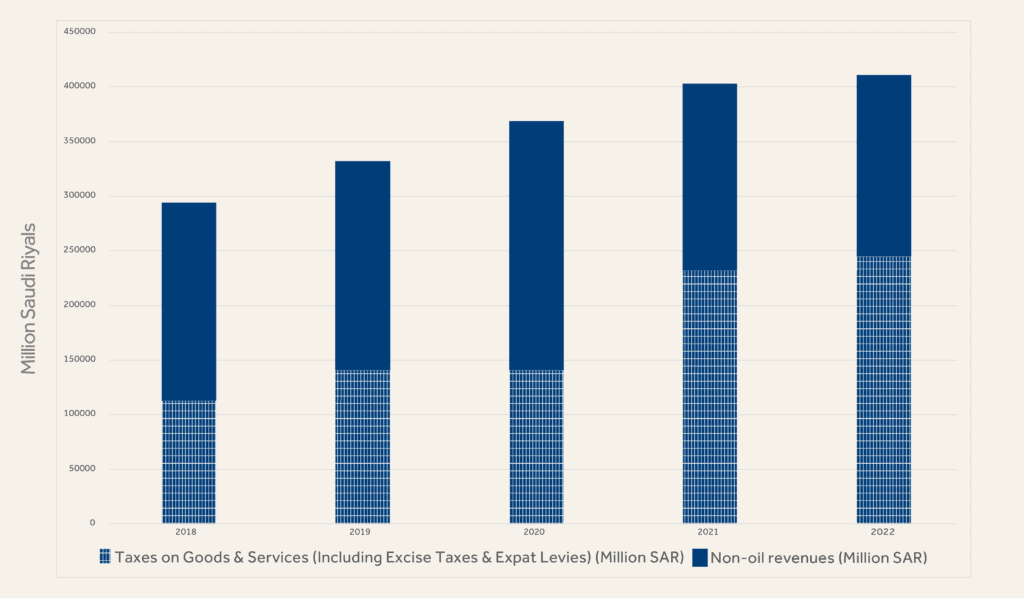

The implementation of VAT stimulated non-oil revenue generation, as evidenced by figure 4. Tax revenues surged, reaching an estimated 166 billion riyals in 2018, a remarkable 89.4% increase from 2017. Taxes on goods and services (including excise taxes and expat levies) were estimated to account for as much as 113 billion riyals in 2018, marking an impressive 187.9% surge relative to 2017. VAT revenues alone were estimated to amount to 45.6 billion riyals, surpassing budget estimates by 101.5%.45 The fiscal deficit continued to shrink due to the recovery of oil revenues and the surge in non-oil revenues, reaching around 5% of GDP in 2018.46 In 2019, lowering the VAT registration threshold and gradually increasing expat levies further stimulated non-oil revenue growth. Tax revenues were estimated to reach 203 billion riyals, 20.5% higher than in 2018. Taxes on goods and services alone were estimated to have accounted for up to 141 billion riyals.47

The IMF welcomed these measures but cautioned that while Saudi Arabia’s fiscal deficit shrank to approximately 5% of GDP in 2018, the government’s spending trajectory exacerbated the economy’s vulnerability to future oil shocks.48 Indeed, public expenditures and government consumption grew by 23% and 4.5%, respectively.49 The country’s high spending bill also acted as a drag on the Fiscal Balance Program, and in 2018, the government pushed back the target date of balancing the budget from 2019 to 2023.50 That same year, authorities anticipated expenses associated with several compensatory measures, including commitments to bear VAT on behalf of Saudi citizens and the Citizen Account Program, which was estimated at 1% of GDP in 2018.51

The fiscal deficit persisted in 2019, as the surge in non-oil revenue coincided with expenditure increases estimated at around 8.5%.52 The global pandemic and the crash in oil prices in 2019 further worsened the country’s economic woes. As economic activities decreased and health spending increased, the country’s budget deficit widened, reaching 9.8% of GDP in 2020.53

The tripling of VAT in 2021 and recovery in consumption levels as lockdown measures were relaxed reflected positively on tax revenues. These surged to approximately 295 billion riyals, a 30.2% increase from 2020.54 Taxes on goods and services alone were estimated to reach 232 billion riyals, 41.8% higher than in 2020.55

The growth in non-oil revenues—sustained mainly by the tripling of VAT—in addition to the recovery of oil revenues, alleviated the fiscal deficit by approximately 8.4 percentage points, contracting it to 1.4% of GDP in 2021.56 In 2022, a fiscal surplus of 3.2% of GDP was recorded for the first time since 2013.57

Figure 4: Non-oil Revenues and Revenues from Tax on Goods and Services- Saudi Arabia (2018-2022)

Source: Figure constructed by the authors using data from the Saudi Central Bank Portal for Open Data and Saudi Arabia Ministry of Finance.58

Impact on Consumption and Investment

The impact of taxes, including VAT, on inflation, consumption, and investment is challenging to assess and has long ignited debate in academic and policy discourses.59 For instance, when evaluating the effects of VAT on inflation, diverse and conflicting findings surface from comparative analyses across different countries.60

The introduction of VAT in Saudi Arabia, which coincided with energy price reforms, resulted in heightened inflationary pressures.61 The average consumer price increased by 3.3 percentage points during 2018, growing from -0.8% in 2017 to 2.5% in 2018.62 Similarly, following the tripling of VAT later in 2020, the inflation rate increased by 5.5 percentage points from -2.1% in 2019 to 3.4% in 2020.63

The primary argument against VAT, when it comes to consumption, revolves around regressivity. VAT may reduce the disposable income of low-income groups, leading to a loss of consumption. However, the impact of VAT on consumption is thought to hinge on the degree of exemptions and, most importantly, the existence of compensatory measures, like the Citizen Account Program and cost-of-living allowances for public employees.64 The effectiveness of these measures was evident as private consumption grew by 2.2% in 2018.65 Government initiatives for households and the private sector continued to prove effective in cushioning the detrimental impact of fiscal reforms following the lowering of the VAT threshold in 2019. This is reflected in a private consumption growth rate of 4.4% in the first half of 2019 relative to 2.6% in 2018.66

VAT is expected to stimulate investment. In many countries, it replaced tax regimes that taxed capital products and favored saving and productive investments over consumption.67 In Saudi Arabia, private investment experienced a slight surge in 2018. The Saudi Purchasing Managers Index (PMI)68 in 2018 averaged 53.7 points, reflecting enhanced private-sector economic activity.69 In 2019, when the VAT registration threshold was lowered, private investment improved, with PMI attaining a four-year record score of 58.3 at the end of the year.70 In 2021, one year after the VAT rate was tripled, PMI recovered by 6.6% as of quarter three following a global recession in PMI levels in the aftermath of the pandemic.71

VAT’s Impact on Public Perception

While the imposition of VAT has had a positive immediate economic impact, it has also led to criticism of the policy and, at times, the state on social media. Adopting this policy was significant for Saudi citizens and their government as it could disrupt state-society relations. Until 2018, the Saudi regime required almost no financial contribution from citizens and provided them with generous social benefits.72 In exchange, citizens were given little political representation. Therefore, it was expected that introducing an indirect tax could upset citizens. Saudi decision-makers were aware of this; along with their GCC counterparts, they had considered introducing VAT as early as the 1990s but held off despite IMF encouragement.73

Perhaps surprisingly, neither introducing nor raising VAT has led to traditional forms of contestation in Saudi Arabia. This raises questions about how Saudi citizens feel about being taxed and the reasons behind their inaction. Are they unhappy but cannot protest due to the closed political climate? Or are they not contesting the change because they accept that the current economic model is unsustainable? Understanding how citizens perceive this reform is the first step towards exploring the impact of VAT on state-society relations in Saudi Arabia.

This imposition seems to have been well-received among Saudis who work in accounting, auditing, and finance. Online questionnaire data show that most respondents were aware of the tax and understood its positive effect. Specifically, nearly 80% agree or strongly agree that VAT positively affects tax returns, over 65% agree or strongly agree that it is the best type of indirect tax, and more than 61% agree that it has helped prevent tax evasion. Overall, around 63% thought the Saudi experience with VAT was successful, which may be surprising, given that nearly 80% agree or strongly agree that it raised commodity prices. However, there were concerns over the implementation of the policy. Over 53% perceived obstacles in implementation. Furthermore, the exemption laws for certain services and equipment raised questions about the fairness of the policy, with over 46% of respondents agreeing that these exemptions leave the taxpayer with a sense of unfairness.74

Younger, less specialized Saudis are less accepting of the VAT policy, according to data from a survey of undergraduate students at the University of Hail.75 This may be due to a lack of familiarity with its mechanisms, such as how it is implemented and redistributes general revenues. While awareness of VAT among young Saudis is high at 89%, over 42% do not understand how VAT would be implemented. A significant portion of young Saudis perceive the policy in a negative light. Around 45% view it as a taxation system that is not efficient, and the same proportion thinks it does not promote income equality. This is predictable given that VAT increases the cost of services and goods for everyone regardless of income and leads to higher living costs and business compliance costs. Furthermore, over 34% thought VAT was not instrumental in generating and increasing income for the country. Interestingly, survey data suggests that respondents’ consumption behavior did not change due to the imposition of VAT; accordingly, younger Saudis still spend regardless.

Conclusion

The imposition of VAT in Saudi Arabia represents a pivotal moment in the country’s economic trajectory, signaling a proactive response to the challenges posed by dwindling oil reserves and volatile oil prices. This move, along with accompanying fiscal reforms, reflects a strategic shift towards revenue diversification and fiscal sustainability, acknowledging the limitations of the traditional rentier model. The introduction of VAT has yielded significant economic dividends, contributing substantially to government revenues and aiding in reducing the fiscal deficit.

However, beyond economics, VAT has prompted critical reflection on state-society relations in Saudi Arabia, highlighting the interplay between economic policy, societal expectations, and political dynamics in shaping public attitudes toward taxation. While concerns were raised about potential citizen backlash, particularly in a society accustomed to minimal financial obligations, the public response has been relatively subdued. This could suggest potential understanding among some citizens of the imperatives driving fiscal reform.

The imposition of VAT has sparked discussions about fairness, efficiency, and the social contract between the state and its citizens. While segments of the population have voiced reservations about the potential impact on consumption and income inequality, others have recognized the necessity of diversifying revenue streams for long-term economic stability. The divergent perspectives underscore the importance of engaging with citizens in shaping fiscal policies and fostering transparency and accountability in the implementation process.

Saudi Arabia’s experience with VAT offers insights for other Gulf states like Kuwait and Qatar, which are yet to implement the tax. One key takeaway concerns the importance of understanding how VAT works in shaping public perception of the tax, as evidenced by survey data indicating a negative perception of VAT among Saudis who lack understanding of the tax system. This is especially important in contexts where citizens are unfamiliar with sales tax. Here, public education and awareness campaigns could prove useful in mitigating misconceptions, building trust in the tax system, and fostering acceptance and support for fiscal reforms among citizens.

Another important insight is the impact of perceived inequality on public acceptance of VAT. To ensure that VAT imposition is well received by citizens, Gulf states should consider socio-economic diversity within their populations and design VAT policies with the distributional effects on different segments of society in mind. Measures such as targeted exemptions or rebates for essential goods and services can alleviate the burden on vulnerable groups, including low-income foreign workers, and mitigate regressive impacts.

Finally, while VAT can contribute to revenue generation, its implementation can lead to adverse effects, such as inflation. Policymakers should adopt compensatory measures to mitigate these negative impacts alongside VAT adjustments. These measures may include implementing monetary policies to control inflationary pressures, investing in infrastructure to boost productivity and competitiveness, and promoting diversification of the economy to reduce reliance on oil and gas revenues. By adopting a comprehensive approach that addresses the broader economic context, Gulf countries can ensure that VAT reforms contribute positively to sustainable economic growth while minimizing potential drawbacks.