The Wages of War:

Yemeni Gunmen for Hire

Issue Brief, April 2025

Key Takeaways

The Impacts of the Ongoing War: Yemen’s long-running conflict has crashed the country’s economy, leading to spiraling poverty, unemployment, and the disintegration of traditional social support networks. The ensuing humanitarian crisis has become a breeding ground for exploitation, offering organized groups access to recruiting vulnerable Yemeni youth into armed conflict or dangerous illicit activities

Yemeni Fighters’ Motives: They are driven by three main motivations: ideology, politics, and material gains. These motivations may overlap according to the individual circumstances of fighters and those who recruit them.

The Challenge of Returning Fighters: Fighters returning from foreign battlefields face major challenges and threaten the stability of Yemeni society in ways reminiscent of fighters returning from Afghanistan in the 1980s. Without proper reintegration, these fighters risk destabilizing local communities by importing combat skills and extremist ideologies

Reciprocal Regional Impacts: Yemen is no longer merely an arena for local conflicts or proxy wars; it has evolved into an exporter of fighters to multiple conflicts in the region and beyond. This reflects overlapping regional and international interests and the transformation of local conflicts in the MENA region into proxy wars.

Introduction

Over a decade of relentless conflict, Yemen’s longest modern war, has fundamentally shattered the country’s social, economic, and political foundations. Famine, extreme poverty, and economic collapse have pushed Yemenis to make grim choices to survive, including joining smuggling networks, working illegally in neighboring countries, or signing up to fight for a wage in conflicts well beyond Yemen’s borders.

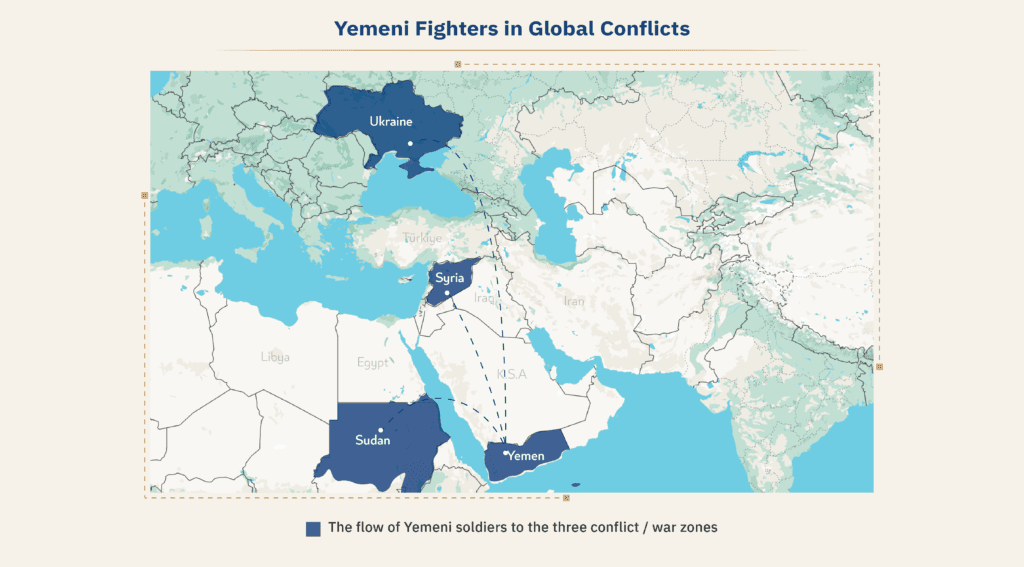

While the phenomenon of Yemeni fighters overseas has received little media coverage, online reports and semi-official statements confirm they have been deployed in multiple arenas, including Syria, Iraq, Sudan, and even alongside Russian forces in Ukraine. While this is an alarming development, it is not surprising as Yemen has been mired in a civil/proxy war since the 2011 popular uprising against the regime of Ali Abdullah Saleh.

Yemen has witnessed similar scenarios in its modern history. Yemeni fighters have taken part in conflicts in Afghanistan, Palestine, and Iraq, for ideological reasons; the government also deployed forces to assist Iraq during its 1980-1988 war with Iran, and Libya in its 1978-1987 conflict with Chad. However, the risk posed by the current wave lies in its unprecedented scale, the diversity of conflicts concerned, and the complexity of fighters’ motives.

Yemeni fighters overseas are driven by three primary motives, which may overlap in some cases. The first is ideological, as in the case of the Houthis’ support for the “Axis of Resistance” by sending fighters to support Bashar al-Assad’s regime and Hezbollah forces in Syria. The second is political, or aimed at achieving shared interests, as in the case of Emirati-backed Yemeni fighters in Sudan. Lastly, purely financial incentives, often intertwined with other motives, drive recruitment, as seen in Russia’s exploitation of Yemenis as human shields in Ukraine with promises of substantial payments.

This issue brief examines the phenomenon of Yemeni fighters overseas, emphasizing that this phenomenon cannot be addressed in isolation from efforts towards a comprehensive solution to the war in Yemen. This necessitates a deep understanding of the relationship between economic and social fragility on the one hand and recruitment of fighters on the other. It also demands comprehensive recovery policies that go beyond humanitarian aid to rebuild productive sectors of the economy and create sustainable economic opportunities. This requires an integrated strategy to address deeper social and economic issues that go beyond the narrow military and security lens. Such strategy should integrate the roles of local, regional, and international actors, along with international accountability mechanisms.

From Oil Fields to Battlefields: Yemen’s Economic Decline and the Recruitment Surge

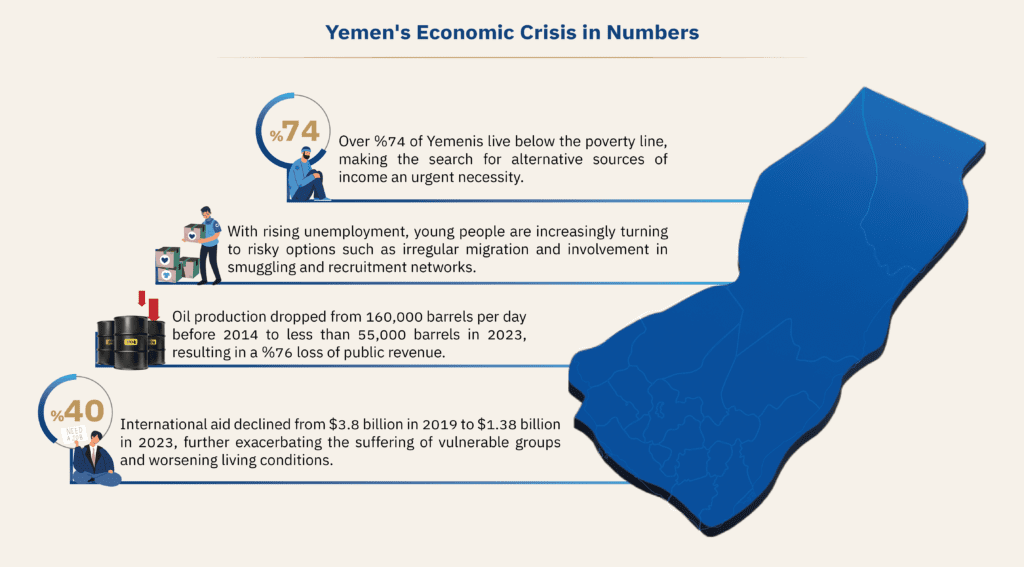

Economic and social factors have conspired to weaken Yemeni society in ways that create a fertile environment for exploitation. Media reports have suggested that the majority of Yemeni fighters were unemployed for more than two years before being recruited.1 This reflects a direct relationship between socio-economic vulnerability and the likelihood of joining smuggling networks or armed groups. Recruiters leverage Yemen’s stark economic circumstances, represented by striking unemployment and poverty rates, over 33% and as high as 74% respectively, leaving young people with few alternative opportunities.2

In such a situation, joining an armed group or smuggling network becomes one of the few viable ways to make an income, given the collapse of traditional productive sectors. This collapse is perhaps most reflected in Yemen’s oil industry: available statistics indicate that oil production has decreased from 150,000-200,000 barrels per day (bpd) prior to 2014 to less than 55,000 bpd in 2023, slashing public revenues and crippling the state’s ability to pay salaries and provide basic services.3 International aid to Yemen also decreased from $3.6 billion in 2019 to $1.38 billion in 2023.4

Source: CEIC Data, Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)5

Concurrently, the disintegration of traditional social networks has eroded family and community ties, leaving young people feeling isolated and alienated as traditional social safety nets lose their resilience. Over the past decade, Yemeni families witnessed a radical shift in their revenues, particularly due to a 75% decline in the value of the Yemeni riyal between 2015 and 2023, which led 45% of Yemeni families to resort to extreme coping mechanisms such as withdrawing children from school and marrying girls at an early age.6

These conditions make signing up to fight, in Yemen or overseas, an increasingly attractive option, given that the salary of a fighter (who may be supporting an extended family) can range from $300 to $1,000 per month—three times the wage of the best available civilian jobs in Yemen.7 Alongside financial benefits, armed groups also provide a sense of belonging and shared identity, which helps compensate the loss of traditional social support mechanisms. Thus, joining an armed group should not only be viewed as a financial option, but also a means of restoring dignity and personal pride, ostensibly offering a solution to the social isolation suffered by a large segment of society as a result of a war that has been underway for more than a decade.

Fragile economic and social conditions have given rise to a parallel economy through the creation of local intermediaries (recruitment brokers and smuggling networks), a new class of economic actors, who receive commission for each fighter recruited for external conflicts. These networks operate primarily in poor rural areas and Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps, where the costs of recruitment are low and there is relatively high take-up, given IDPs’ dire need for work and an income. For example, the World Food Programme reported that 70% of IDPs were food insecure.8 The World Bank warned of an even greater danger: the long-term impact on human capital, as poverty is passed down to future generations, undermining prospects for Yemen’s economic recovery.9

The Houthis’ Ideological Pragmatism

Recent developments have revealed a strategic shift on the part of the Houthis, who have evolved from belligerents in Yemen’s civil conflict to carving out a growing role across the region. The Houthis present a new model for armed groups, combining the ability to manage multi-level conflicts, and build cross-border alliances with their penetration of the local social fabric. What distinguishes this model is its ability to adapt to regional developments and employ them to its advantage. Since intervening in support of Gaza in October 2023, by launching missiles and drones at Israel and attacking cargo ships in the Red Sea, the group has sought to assert its presence as a regional player able to wage battles on multiple levels, both inside Yemen and in the wider region.

A key aspect of this transformation is the complex pattern of relationships that the group is weaving beyond Yemen’s borders by exporting its fighters to multiple arenas—Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.10 Unlike other Yemeni fighters, who head overseas to fight for financial rewards, or under pressure related to political interests, Houthi fighters are primarily motivated by ideology. This makes their impact even more dangerous upon their return. When these fighters return, with combat experience and imbued with increasingly radical ideas after direct contact with extremist militias, they could form the nucleus of a deeper transformation in the structures both of the group and of Yemeni society.

This transformation has implications beyond a direct threat in the Red Sea: it could redraw the contours of the region’s geopolitical map. The fall of the Assad regime in Syria and the influx of pro-Assad fighters, alongside Houthi militants, from Syria into Iraq, provides the Houthis an opportunity to broaden their relations by recruiting Syrian fighters with extensive combat experience. This trend is not entirely new: since the beginning of the war in Yemen, the group has benefited from the expertise of fighters from Lebanon and Iraq, including in guerrilla warfare tactics, and developing the group’s missile capabilities.11

Another layer of complexity is added by a reported rapprochement between the Houthis and Al-Qaeda following the October 7 attacks, as well as the Houthis’ growing relations with Somalia’s Al-Shabaab movement and their efforts to recruit migrants from the Horn of Africa. All this reveals a level of political pragmatism that transcends sectarian and ideological limits. On the domestic level, the Houthis have stepped up their mobilization and recruitment efforts since October 7, targeting the marginalized “muhammashīn” group,12 exploiting their chronic social and economic suffering and employing an ideological discourse aimed at tapping into the historical injustice such groups have suffered. This combination of regional influence and local entrenchment will make it increasingly difficult to dismantle the Houthi network or contain its growing influence, notwithstanding its reinstatement to Washington’s terrorism blacklist.

Yemenis in Sudan’s Conflict

Various media have reported that Yemenis are fighting among the ranks of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Sudan, an allegation repeated by the President of the Sudanese Sovereignty Council in September 2023, five months into the war.13 This indicates that Yemen has transformed from an arena for a local conflict—albeit one implicating regional powers—into an exporter of mercenaries, linking it into a complex network of political and economic interests and trade-offs in various conflicts across the region.

The war in Sudan is more than a local power struggle between the army and the RSF; it is one link in a region-wide chain of struggles for influence. New York Times and UN led investigations, respectively, revealed the UAE’s provision of extensive support to the RSF, including by smuggling and paying for weapons, and by operating drones out of bases in Chad.14 The UAE’s involvement has been countered by Egypt, Russia, and Iran’s support to the Sudanese army.15 Amidst the ongoing war in Sudan and a rising death toll, increasing displacement, and ravaged cities and infrastructure, the United States announced sanctions on leaders and companies registered in Hong Kong and the UAE, used by either the Sudanese army or the RSF to circumvent the arms embargo on Sudan.16

The growing relationship between the UAE and the RSF can be attributed to various factors, primarily political and financial gains and the military experience of the RSF, who previously fought—also with Emirati coordination—in Yemen alongside the Arab coalition forces, and in Libya in support of Khalifa Haftar.17 Therefore, it is not surprising that Yemenis are allegedly deployed in Sudan in support of the RSF. This ultimately maintains the cycle of violence with investment from regional powers as a tool to further their own interests.

Yemenis in the Russia-Ukraine War

Social media sites have been ablaze with clips and posts about hundreds of Yemenis fighting alongside Russian forces in Ukraine. Their recruitment represents a model of the exploitation of humanitarian crises in international conflicts. Case studies such as the story of “Hammoud,” interviewed by the authors, reveal that organized networks are exploiting the fragility of Yemenis’ economic and social situations both at home and in the diaspora. Hammoud’s example is representative of the tragedy facing young Yemenis seeking a better life outside the country and attempting to support their families, but falling prey to organized recruitment networks, who lure them to the fight with promises of salaries of up to $10,000 and Russian citizenship.18

Once Hammoud arrived in Moscow, his passport was confiscated and he was forcibly put through a brief military training course before being sent to the battlefront as a human shield in Russia’s war with Ukraine. Other cases reveal that some Yemenis had prior knowledge that they were heading to the front lines, but felt they had little choice given their country’s dire economic situation. These stories encapsulate the tragedy of an entire generation of Yemeni youth, trapped between the hammer of civil war and the anvil of extreme poverty. They also expose the stark absence of international accountability mechanisms, a major factor in the persistence of this phenomenon. Despite diplomatic efforts, including by the Yemeni embassy in Moscow, the international response remains slow and ineffective. By contrast, human traffickers continue to operate with relative freedom, taking advantage of loopholes in the international legal system and the weakness of monitoring and accountability mechanisms.

Alleged Houthi links to the recruitment of Yemenis to fight in Ukraine is fueled by the fact that Abd al-Wali Hassan al-Jabri, who runs a recruitment company, is a notable Houthi politician.19 However, recruitment efforts have extended beyond the areas under the group’s sway in the north of the country, reaching all of Yemen’s most densely populated areas, including Taiz, Marib, and Aden, regardless of the map of political or ideological control on the ground. That said, the Houthis have made indirect strategic gains beyond the financial returns from recruiting Yemenis, as evidenced by intensified Russian naval activity off the Yemeni coast and the arrival of a wheat shipment to the Houthis last summer, in addition to negotiations over potential arms deals.20

Perhaps the most important development in this context is Russia’s growing need, in light of developments regarding the war in Ukraine, for sources of leverage in the Middle East, especially since Donald Trump’s return to the White House and the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria. This may explain Russia’s growing interest in strengthening its influence in the region through various means, including by signing a strategic cooperation deal with Iran and creating opportunities for communication and cooperation with local actors such as the Houthis.21

On another level, the issue of the recruitment of Yemenis to fight in the war in Ukraine has implications beyond the local humanitarian and political tragedy of Yemen itself, exposing deep flaws in the rules-based international system. What we are witnessing today is not a passing phenomenon or an isolated case; this pattern of exploitation extends to the recruitment of fighters from African countries, India, Nepal, and North Korea, forming an integrated global system that turns the suffering of the vulnerable into a tradable commodity in regional and international conflicts.22

Conclusion

This combination of ideological, political and material motivations, combined with increasing deployments of Yemeni fighters from Sudan to Ukraine, poses a serious challenge—not only to the future of Yemen, but also to regional stability and international security. The combination of fighters returning from multiple arenas, local marginalization, and immigration from the Horn of Africa creates a fertile environment for the growth of violence and extremism. It turns Yemen from a single conflict arena into an exporter of instability. When such fighters return home, armed with combat experience, new networks of relationships, and extremist ideologies, they will pose a serious threat to social peace and the chances of future stability in Yemen and the region at large.

The historical experience of Yemeni fighters returning from Afghanistan in the 1980s provides a case in point for such risks. These fighters were later deployed in domestic conflicts, notably alongside government forces against the Yemeni Socialist Party in Yemen’s 1994 civil war. Their failure to reap personal and societal rewards from this battle pushed many to search for alternatives, a dynamic that contributed to the establishment of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in 1996, further complicating Yemen’s political and security landscape.23

Given the complexity and chaos rocking the region, a local reading of events is no longer sufficient to understand these shifts. Foreign interventions in Yemen and Sudan have gone beyond traditional support for one party or force at the expense of another, and evolved into a complex, interconnected cycle of investment in violence as a tool to further various interests.

The phenomenon of Yemenis fighting overseas exceeds the dimensions of the individual human tragedy, constituting a multi-level, structural challenge. At the social level, the phenomenon is leading to the dismantlement of traditional support networks in Yemeni expatriate communities, where a climate of fear and suspicion is coming to prevail, undermining their ability to adapt and integrate economically. Repeated experiences of exploitation may lead to a crisis of trust between migrants and official institutions, hindering efforts by legitimate organizations to provide assistance and support. Host countries, too, find themselves facing the dilemma of balancing their duty to protect workers, migrants and refugees against the requirements of their national security, posing additional administrative and legal challenges. At the regional level, the transformation of Yemeni fighters into cross-border mercenaries will fuel diplomatic tensions between the countries of origin, transit, and destination, complicating peace efforts in Yemen and undermining cooperation to combat human trafficking and the growth of mercenary networks.

To address these issues, the internationally recognized government of Yemen should strengthen its monitoring mechanisms by establishing a central database to track the movements of Yemeni fighters outside the country, particularly individuals and networks involved in recruitment efforts. National awareness campaigns should be launched to educate potential fighters on the risks of taking part in foreign conflicts and the devastating impact this can have on their communities. Diplomatic missions should also play an active role to protect Yemeni workers abroad, by providing legal and social guidance.

Yemen’s regional neighbors, for their part, should develop a joint mechanism to combat recruitment and human trafficking networks, including intelligence exchange and security coordination to enhance the monitoring and documentation of fighters’ cross-border movements. In addition, given Yemen’s dire economic conditions, it is vital to create jobs for the youth, as unemployment is a key pressure point for recruiters. Donor countries should therefore step up their support for economic development, community, and vocational rehabilitation programs in Yemen, especially in the poorest areas, as improving living conditions may prove an effective tool to reduce the motivations driving migration and recruitment. The U.S. decision to re-classify the Houthis as a terrorist group may have created an opportunity to pressure the group and its funding networks, but it could also complicate efforts to find a political solution, as well as jeopardizing the provision of development and humanitarian support to Yemen’s people.

Finally, the international community must support the implementation of UN resolutions aimed at ending the war and establishing peace in Yemen, including the arms embargo and sanctions on the actors involved in recruiting fighters. It should also work to bolster the efficacy of monitoring mechanisms for these resolutions.