The Gulf and the Horn of Africa:

Investing in Security

Issue Brief, December 2024

Key Takeaways

The Horn of Africa is Vital to Gulf Interests: The Horn has become a key area in the foreign policies of the Arab Gulf states, particularly the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. This is driven by two major motives: economic investments and security.

Gulf Countries must Navigate a Complex Security Environment: Gulf countries have primarily focused their security strategies in the Horn on countering the perceived threat from Iran. As the GCC states expand their political footprint, their strategies must consider the rise of violent extremism and interstate conflicts across the Horn.

The Economics-Security Nexus: Immense economic opportunities are accelerating Gulf countries’ investments in the Horn. This strategy is closely intertwined with security considerations. Investments could promote peace and stability in the Horn, which in turn could safeguard Gulf states’ security interests.

The Risk of Militarization: While the Gulf countries have benefited from their involvement in the Horn, the region’s militarization and inter-Gulf rivalries have exacerbated long-standing conflicts.

Introduction

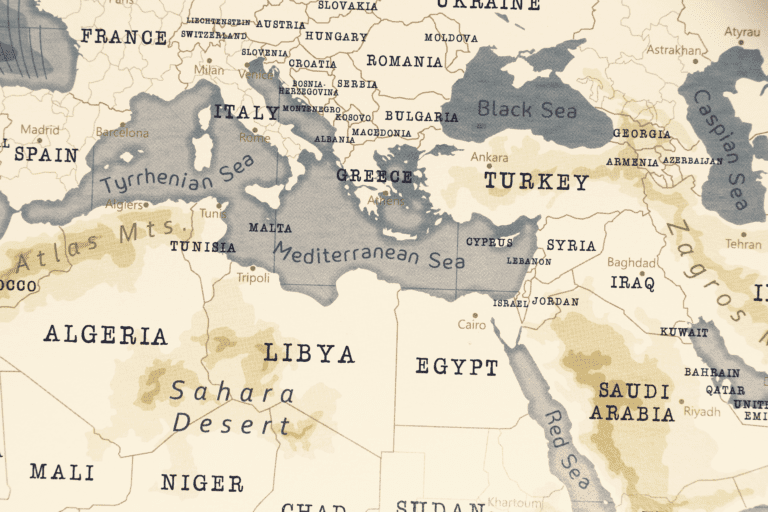

The Horn of Africa (HoA)1 and the states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) share a long history of commercial, cultural, religious, and security ties. In recent years, relations between both witnessed consequential developments, primarily within the security and economic realms. These domains have grown to hold an important role in ties between both regions due to the global strategic importance of the Red Sea, a vital maritime route.

Global and regional powers’ expanding engagement with the Horn of Africa is driven by several factors, notably the region’s rich natural resources—key minerals, oil, gas, arable land, and water.

During the Cold War, the region was a battleground between the United States and the Soviet Union. Today it hosts great powers (the United States, China, and Russia), and several middle powers (France, Italy, Iran and Türkiye), as well as a number of GCC states.

Three Gulf states, namely the UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia are increasingly pursuing their interests in the HoA to counter the presence of their respective rivals and/or to support the region’s political regimes. Since 2017, Saudi Arabia and Djibouti have been in discussions to build a Saudi military base in Djibouti;2 while the base does not appear to have materialized,3 both countries remain committed to cooperating on Red Sea maritime security.4 In 2024, Saudi Arabia signed a contract with Djibouti to build a logistics base which would serve as a hub for exports across Africa.5 Saudi, along with Qatar, and the UAE have also made substantial investments in the region, including in agriculture, energy, real estate, banking, manufacturing, construction, logistics and shipping, consulting and business services, telecommunications, hospitality and tourism, healthcare and social services, education, and mining.6

This issue brief focuses on Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE’s heavy presence in the Horn and their evolving relations with its respective governments. It particularly highlights the security and economic drivers of the Gulf states’ involvement in the Horn. It also addresses the motivations underpinning their interest in the region, and the factors pushing governments in the Horn to engage with the Gulf states.

The Scramble for Influence in the Horn

Home to over 200 million people,7 the HoA is among the world’s most conflict-prone areas, partly due to its strategically critical location, local politics and history, and the impact of major events in neighboring regions.8 Today, the region has become central to the Gulf countries’ interests.

Saudi Arabia has been involved in the Horn, particularly Sudan and Somalia, since the 1970s. Riyadh’s engagement was first catalyzed by the Arab Israeli conflict and then by its efforts to prevent the spread of Shiism in Africa following Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution.9 At the time, the UAE and Qatar were far less engaged with the Horn countries. The 2008 financial crisis marked a turning point. All three Gulf countries sought out economic opportunities in regions less affected by global economic downturn which gave the Horn increased significance.10

Historically, the Red Sea facilitated the trade of goods and movement of people between the East African kingdoms and the Gulf states. Economic exchanges fostered cultural ties, spreading Islam and shaping a shared identity. This longstanding historical bond continues to influence the Gulf states’ foreign policies as they endeavor to strengthen relations with Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan, Eritrea, and Djibouti, drawing on a common cultural legacy. This partially explains “the frantic pace of initiatives by Gulf states to project influence in the region and align leading African actors with the objectives pursued by them.”11

Gulf countries’ growing interest in the Horn in the 2000s can also be attributed to their recognition of the region’s strategic importance as a gateway to the Indian Ocean and beyond. This geographic advantage allowed the three Gulf countries to facilitate trade between East Africa and the rest of the world, actively shaping the region’s economic dynamics. But this alone does not explain the Gulf’s deep involvement in the Horn.

Drivers of the Gulf States’ Involvement in the Horn

Security and economic interests are the main motivations driving the Gulf powers’ interest in the Horn of Africa. Both spheres are deeply intertwined, reflecting an engagement that is part of a larger geopolitical strategy aiming to navigate a complex web of regional dynamics and global power shifts. The following sub-sections lay out some of the drivers of Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE’s engagement with Horn countries.

Geopolitical Factors

Throughout the postcolonial era, the HoA has been plagued by endemic fragility, leading to numerous conflicts, piracy, terrorism, and weak or failed states. This has made the region susceptible to external interference. The increasing importance of the Red Sea in global geopolitics intensified external powers’ interest in the Horn.12 The sea forms a critical waterway for global trade, with the Suez Canal to the north and the Bab el-Mandeb Strait to the south. Moreover, Washington’s ostensible disengagement from the Middle East and “Pivot to Asia” since the Obama administration13 further accelerated regional power rivalries, enticing regional actors to project their power in the Horn with aims to restructure regional systems around their interests.

The 2011 Arab uprisings and the Muslim Brotherhood’s activism across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) including in Egypt and Sudan prompted Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE to form alliances in MENA countries and beyond—including in the HoA—to counter what they perceived as an existential threat.14 While Qatar was warmer towards Islamist-leaning governments, Saudi Arabia and the UAE opposed their growing popularity and assumption of power in certain cases.15 At the time, Doha, Riyadh, and Abu Dhabi had to carefully manage regional dynamics to prevent the escalation of tensions in the region.

A Theater for Rivalries

In 2015, Saudi Arabia, along with the UAE, and other countries, intervened militarily in Yemen’s civil war, largely, to limit the influence of the Houthis and Iran. The UAE sought to establish a military base in Eritrea and Somaliland16 while Saudi Arabia affirmed its intent on building one in Djibouti17 to serve as a platform for military operations in Yemen. Saudi Arabia and the UAE also sought to protect key waterways for global trade and the flow of oil, which drove them to invest in ports and military bases in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.18 Qatar and Türkiye, too, stepped up their involvement in the region following the 2011 Arab uprisings.19 Qatar showed a greater willingness to collaborate with governments or actors affiliated with Islamist organizations, whereas the UAE engaged with actors countering Islamist political actors.

Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt’s diplomatic and economic blockade of Qatar between 2017 and 2021 enhanced Qatar-Türkiye cooperation. In 2018, Qatar obtained a $4 billion contract with Sudan to modernize its Suakin port.20 However, the deal froze just a year later due to domestic instability in Sudan.21 In 2019, the Qatar Ports Management Company (Mwani Qatar) launched negotiations with Somalia for an investment partnership contract to build the Hobyo port in the central region of Mudug, near the Bab el-Mandeb strait, although the deal fell through and Türkiye took the project over in 2024.22 Doha also granted Somalia a fleet of 68 armored vehicles.23

Doha and Abu Dhabi have competed for the acquisition of port projects in Mogadishu and Somalia’s breakaway territories respectively.24 In recent years, Djibouti has gravitated towards Saudi Arabia. This shift was catalyzed by Djibouti’s 2021 rift with the UAE.25 This rift was triggered when the former claimed control of a Dubai Ports (DP) World operated, and partially owned, container terminal in 2018.26 Saudi Arabia’s efforts to establish a military base in Djibouti,27 and the UAE’s investments in Somaliland’s Berbera Port,28 therefore highlight the increasing militarization of the region.

Asserting Influence through Commercial Interests

The GCC states’ political involvement in the Horn has enabled them to protect their wider maritime neighborhood, assert regional influence, and bolster their commercial interests. The UAE, for instance, is gradually becoming a key security player in the region.29 For their part, Horn governments have capitalized on the Gulf states’ growing interest in their neighborhood, leveraging political alliances in the Gulf to strengthen their own regimes, as well as to protect and advance their strategic interests. Ethiopia, for instance, has sought to become a regional hegemon, while smaller states like Eritrea and Djibouti, and the breakaway region of Somaliland, have played on their strategic locations and exploited external powers’ rivalries to position themselves as crucial hosts of military bases such as the UAE’s 2015 base in Eritrea’s port city of Assab. The base was later dismantled in 2021 after the UAE withdrew from the war in Yemen.30

To achieve their goals in the HoA, the Gulf states have pursued diverse strategies. Saudi Arabia has concentrated its efforts on sectors such as education and financial investments. Conversely, the UAE has directed its attention towards agricultural development, the management and development of port facilities, and the security sector.31 In December 2022, for instance, the Sudanese government and a consortium of Emirati companies signed a preliminary $6 billion agreement to develop and operate the Abu Amama port on the Red Sea, which also includes an economic zone.32 However, Abu Dhabi’s alleged support for the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) heightened tensions between the UAE and the Sudanese government and led to the dissolution of the deal in November 2024.33

While they share economic interests in the Horn, the GCC states’ engagement is driven by different motives. With the war in Yemen, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s primary concern was Iranian support for the Houthis along with their fierce rivalry with Qatar and Türkiye which played out across the Horn’s political landscape.34 Shifting regional dynamics, such as the Gulf crisis, gave rise to new regional alliances between Gulf and Horn states. Türkiye and Qatar bolstered their collaboration, whereas the UAE and Saudi Arabia leveraged their influence in the Horn to isolate Qatar.

Political Affairs and Mediation

Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar have also stepped up their political involvement in the Horn. Since the late 1990s, they have engaged in intense diplomatic activity in efforts to pacify interstate boundary disputes and proxy wars in the region. In 1999, Qatar brokered an agreement between Sudan and Eritrea, restoring diplomatic ties that had been severed since 1994.35 In the mid-2000s, Qatar extended its mediation efforts to warring factions in Somalia. Qatar’s political role in the Horn became so prominent that the Ethiopian government cut diplomatic ties with Doha, in April 2008, accusing it of contributing to regional instability. They were not restored until four years later.36 Qatar’s mediation efforts encompassed various conflicts across the Horn, including the 2008 border dispute between Djibouti and Eritrea. However, Qatar withdrew its peacekeeping forces from the border in 2017 arguably due to the Gulf crisis when Djibouti and Eritrea both aligned with the Saudi-led bloc.37 Djibouti and Eritrea restored ties in 2018,38 although their conflict was never definitively resolved.

Qatar has not been alone in seeking a role as a mediator in the HoA. Worried that the war in Yemen would further destabilize the region, Saudi Arabia and the UAE expanded diplomatic efforts to end several conflicts in the Horn. Notably in 2018, under the auspices of Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, Ethiopia and Eritrea, two major rivals in the Horn, signed a peace agreement in Jeddah.39 The two Gulf states succeeded in helping normalize relations between Addis Ababa and Asmara. Despite the Gulf states’ efforts, cyclical tensions between Eritrea and Ethiopia, which have fought repeated wars since Eritrea’s independence in 1993, make the resumption of hostilities a real possibility.

Qatar also mediated the resumption of diplomatic relations between Kenya and Somalia in May 2021,40 six months after Somalia severed ties with Kenya, accusing it of violating its sovereignty and interfering in its internal affairs.41 Qatar achieved this by leveraging its neutral position and its considerable financial resources. This example reinforces the link between the distribution of aid and regional rivalries between GCC countries, which has influenced Qatar’s aid strategies towards the Horn of Africa and has political implications for Somalia’s stability. Qatar’s endeavors are part of a strategy of addressing the underlying causes of conflicts to foster security, peace, and development across the African continent.42 By positioning itself as a diplomatic powerbroker, through relationships with state and nonstate actors, it has been able to leverage its financial power and neutrality to support its mediation efforts and aid interventions.43

The UAE’s strategic approach in the Horn of Africa includes using economic ventures, such as port developments, to safeguard sea trade passages between Asia and Europe and extend its sway in an area that also acts as a conduit between the Middle East and Africa. Since at least 2010, the UAE has established commercial and military outposts (e.g., Berbera in Somaliland and Assab in Eritrea) to safeguard its military, security, and economic objectives in the Horn. It has established, or sought to establish, such footholds in Yemen, Eritrea, Somaliland, Puntland, and Somalia.44 The UAE maintains a relatively high level of discreetness in its strategic engagement with Horn countries to reduce adverse political fallout. Abu Dhabi aims to mitigate any backlash from local communities that might resist Emirati involvement and to protect Abu Dhabi’s global standing, particularly in instances where its outposts have been used to back warring factions.

The primary objective of the UAE’s military installations is to safeguard maritime routes, particularly in the Red Sea and the western Indian Ocean. These areas face multiple security challenges including Houthi assaults on commercial vessels, a resurgence of piracy off the coast of Somalia, and escalating activity by both al-Qaeda and the Islamic State group (ISIS) along the East African seaboard. The UAE’s burgeoning economic interests in the Red Sea, Eastern Mediterranean, and broader African continent create a dual imperative to address instability through economic and militarized interventions. Consequently, since 2023, the UAE has established a security presence on Yemen’s Abd al-Kuri Island, Somalia’s Kismayo, and Amdjarass, at the frontier between Chad and Sudan.45 Inevitably, however, this exacerbates its geopolitical and geoeconomic rivalries with both Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

The Geo-Economic Dimension

The Gulf states’ influence in the Horn draws on a web of complex and interconnected dynamics through holistic strategies that integrate collaboration on security, diplomacy and mediation efforts, and the establishment of robust economic connections. Gulf countries view rapidly expanding African economies as vehicles for broadening their investment portfolios and diminishing their dependency on hydrocarbons. The surge in global food prices in the 2000s prompted the Gulf countries to channel investments into farmland in Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda.46 Qatar, for instance, has acquired Sudanese farmland to enhance its food security.47 Anticipating the continued impact of recent disruptions in global agricultural trade flows—linked to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, and India’s limits on rice exports—food security will likely remain a prominent driver of GCC investments in the Horn.48

The Gulf countries, which depend on food imports for up to 85%49 of their consumption, view agriculture as a key strategic focus and have implemented various measures to ensure a stable food supply. These include substantial investments in East African countries, from Sudan to Somalia. Paradoxically, Sudan and Somalia themselves are host to food insecure populations due to ongoing conflicts; in August 2024, the UAE voiced alarm at the dire humanitarian conditions in Sudan.50 The United Nations reports that approximately 25.6 million people—over half of Sudan’s population—are experiencing severe hunger, with 755,000 on the brink of famine.51 While the ongoing war in Sudan is largely responsible for these dire conditions, these realities raise important questions over foreign countries’ reliance on impoverished countries for their own food security.

Despite challenges, initiatives such as the establishment of the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) revitalized economic relations between the Gulf and East Africa in particular. Launched in 2021, AfCFTA consolidates the continent’s markets into a single entity, which is anticipated to expand to encompass 1.7 billion individuals and generate consumer and business spending worth $6.7 trillion by the year 2030.52This is expected to further spur GCC investments by giving Gulf companies access to a more expansive and integrated African market.

Currently, the UAE ranks as the fourth biggest source of foreign direct investment in Africa, trailing only behind China, the European Union, and the United States.53 In the past decade, the UAE channeled $59.4 billion of investment into Africa. Saudi Arabia and Qatar invested $25.6 billion and $7.2 billion, respectively.54

Total Trade between Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar and Horn of Africa Countries, 2017 to 2021 (US$ Mil)

| Saudi Arabia | UAE | Qatar | |

| Djibouti | $2,494,700.54 | $4,052,361.81 | $129,985.92 |

| Eritrea | $24,786.61 | $1,308,260.43 | $328.65 |

| Ethiopia | $1,371,497.24 | $4,744,679.10 | $47,420.41 |

| Somalia | $585,404.92 | $6,397,363.60 | $38,856.10 |

| Sudan | $5,759,145.25 | $15,001,068.19 | $370,072.41 |

| South Sudan | $7,192.13 | $1,149,511.35 | / |

Source: World Bank Country Profiles, https://wits.worldbank.org/.

*The averages calculated are based on available data for the range and countries indicated.

Conclusion

The Horn of Africa’s geostrategic importance to the Gulf countries has significantly increased in recent years. Countries in the Horn continue to rely on remittances from citizens working in the Gulf states and Gulf investments and trade in the region could contribute to the Horn’s prosperity and help alleviate socioeconomic challenges. However, Gulf rivalries have exacerbated tensions within the Horn in various cases. For instance, in 2017, Djibouti downgraded relations with Qatar following the Saudi-led bloc’s diplomatic rift with the Gulf state.55

More recently, a deal to allow landlocked Ethiopia to have a seaport on the Gulf of Aden, in the breakaway region of Somaliland has the potential to deepen divisions between two nascent coalitions, with Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and allies such as Eritrea and Djibouti on one side and the UAE, Ethiopia, and their affiliates on the other.56 Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Eritrea are united by a common interest in barring other nations from gaining influence in the Red Sea.

These dynamics risk fueling excessive militarization in the HoA. Rivalries among global and regional forces could easily offset any positive developments.57 While rents for military bases bring in much-needed financial support for struggling HoA countries, they cannot, alone, promote development. Horn countries should therefore set their own long-term strategic objectives, foster their political stability and security to attract investment, enhance their images, and diversify their economies.