Power in Yemen:

From Formation to Appropriation

Policy Paper, November 2023

Abstract

This paper explores the evolution of Yemen’s power dynamics and highlights how factions vie for control and perpetuate cycles of conflict. It explores competing groups’ motives and factors that enable political elites to eclipse other factions and stifle equitable representation. Such dynamics have ensnared Yemen in tribal and sectarian disputes. Persistent historical patterns pose threats to peacebuilding, national reconciliation, and the birth of a modern state. The paper elucidates the reasons behind power appropriation, the state’s failure to power-share, the emergence of the Houthi movement, and the recurring patterns of power control. It also suggests solutions for effective power-sharing, equitable resource distribution, universal basic service provision, and policies that can prevent select groups from monopolizing the state.

Key Recommendations

- End Yemen’s History of Power Struggle: All parties involved in Yemen’s conflict should heed history—appropriating power merely replicates historical trends.

- Empower Decentralized Governance: Support is needed to broaden the presidential council and ensure equitable resource distribution with international oversight.

- Balance between Local Autonomy and National Identity: Power should be devolved to local authorities, while maintaining national identity and fostering collaboration with global entities.

- Respect Sovereignty, Secure Peace in Yemen: Regional nations should publicly endorse Yemeni unity, avoid actions that exacerbate conflict, and stop leveraging Yemen’s economic strife for regional gain.

Introduction

Many analyses of Yemen’s ongoing conflict concentrate on either local or external participants. The Yemeni conflict is typically seen through the lens of external influence, neglecting the nexus of tribe, sect, and power, which defines the local participant, tracing back to the birth of the modern state in the 1960s. This dynamic is perhaps what ex-President Ali Abdullah Saleh referenced when he likened ruling Yemen to “dancing on the heads of snakes.”1 In Yemen’s historical tapestry, the tribe stands as a foundational pillar. Sects drive group and state dynamics, and the notion of power appropriation is deeply ingrained. To truly grasp Yemen’s current strife, we must revisit its historical underpinnings, dissect this nexus, and analyze its facets to devise solutions grounded in societal structures that resonate with Yemen’s unique context. This can pave the way for enduring peace and prevent recurrent bouts of conflict and upheaval.2 There is a consensus in the literature that the local context, with its myriad facets, is crucial in shaping a modern state.3

This paper explores Yemen’s history of power struggles that has resulted in perpetual conflict. The current war is merely another round of this cyclical conflict, and the paper aims to highlight Yemen’s endemic power-grabbing.4 This phenomenon is not just about amassing power and wealth; it extends to monopolizing public discourse and values, thereby sidelining others from active participation and representation. Central to the paper’s argument is the idea that Yemen’s recurring power struggles, whether tribal, sectarian, or ethnic, stem from this ingrained culture of power-grabbing. To break this cycle, it is necessary to promote unity, power-sharing, fair resource allocation, universal access to services, and policies preventing disproportionate group dominance.

Historical Context

Many conflate the notions of power and the state. While power has always been tied to political rulership across eras, the idea of a “state” matured during the European Renaissance, with a monopoly of power emerging as one of its defining characteristics.5 Thus, political systems spanning Yemen’s ancient, medieval, and modern eras might not mirror the modern conception of a state despite attempts to build it but are rather a representation of political authority. This holds true even with earnest endeavors to found a state in the modern sense—notably, following the 1962 adoption of a republican framework and the 1990 Yemeni unification.

Power and Tribe

In Yemen, the inception of the state took place within a predominantly tribal society, wherein tribes were intricately tied to productive forces. This connection positioned the tribe as the foundational element in shaping both ancient and contemporary Yemeni states. The Sabaean and Himyarite entities were essentially tribal coalitions. Dominant tribes exerted their influence over various tribes, bringing them under their sphere of control. Additionally, they established alliances with other tribes, culminating in the formation of what was termed the state.6

When a state collapses7 due to internal strife, and a new one takes its place, tribal structures sometimes persist and fill governance-related gaps. This resilience can be traced back to each tribe’s unique territorial claims, demarcated by the distinctive geography of Yemen.8 This landscape has historically enabled tribes to maintain autonomy regardless of the state’s strength. This enduring tribal governance has been a hallmark of Yemeni society, dating back from antiquity to present times. After the September 26th Revolution, tribal chieftains consolidated a form of judicial oversight termed the “judicial control tool,” granting the sheikh the authority to detain individuals on behalf of the state. These leaders also held sway in collecting zakat, reserving a portion for themselves.9

Furthermore, the ruling class has consistently monopolized power and the lion’s share of economic yield, with tribal chieftains integrated within this elite. Yemen’s tribal fabric has seen little alteration to date, rooted firmly in its time-honored socio-legal systems and the extant production relations. Consequently, tribes are not just sociopolitical pillars but the very bedrock of Yemeni society. This intricate tapestry comprises prominent tribes that bifurcate into sub-tribes, which then further subdivide into smaller familial and clan units.10 It is evident that Yemen’s power dynamics stem from its deeply ingrained tribal ethos. The state’s foundational principles of self-governance and autonomy underscore an enduring legacy of independence and power ownership—hallmarks that have manifested across Yemen’s multifaceted historical landscape.

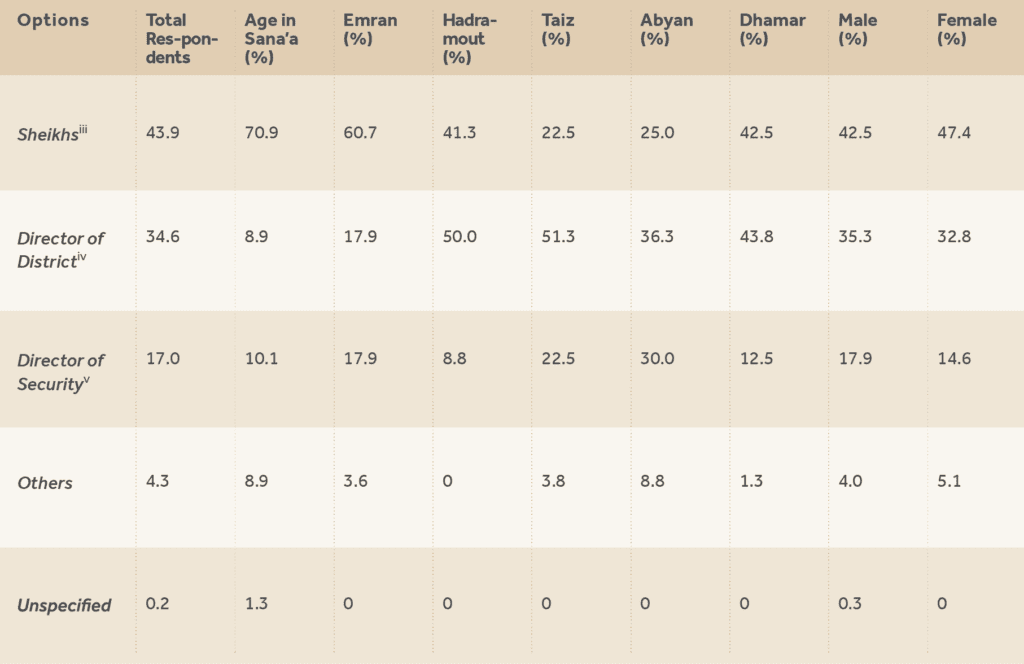

In a 2009 opinion poll conducted across various governorates about the predominant authoritative entity in the region—during Saleh’s rule, which was marked by relative stability and a notable level of state capacity—it was found that tribal sheikhs were deemed the most powerful in the northern highlands. However, their influence waned in the western and southern regions, as depicted in Table1.

Table 1: Opinion Poll – Who is the most authoritative in the region?

Sheikhs11, Director of District12, Director of Security13

Source: Adapted from Adel Mujahid Al-Sharjabi et al., The Palace and the Court: The Political Role of the Tribe in Yemen, 2nd ed. (Sana’a, Yemen: Yemeni Observatory for Human Rights and IDRC [Canada], 2016), 157.14

Power Dynamics and Power-Grabbing

The rise of the state in Yemen was not solely based on tribal loyalties; often individuals outside those tribes utilized and appropriated tribal power. The Zaidi Imamate serves as a notable example. While it restricted the Imamate to two specific tribes, it leaned on the non-Hashemite Qahtani tribal strength to dominate and monopolize power.15 This brings forth a question: Why might tribes support someone from outside their ranks to assume leadership? A prevailing theory suggests the tribes’ sectarian allegiance can sometimes supersede tribal ties. This notion is invoked today when discussing the northern highland tribe support for the Hashemite Houthi group. Yet, history challenges this idea. Tribes have sided with Zaidi Imams even before adopting Zaidism and opposed them post-conversion.16 The support that Zaidi tribes gave to Muhammed al-Idrisi, a Shafi’i scholar, against Zaidi Imam Yahya Hamid al-Din in the early twentieth century attests to this.17 It is evident that tribal decisions often hinge on economic and political factors. This pragmatism plays a significant role, and, at times, tribes align with non-affiliated individuals for neutrality’s sake.

Yemen’s political history oscillates between unification and fragmentation due to the tribes’ pursuit of independence, leading to frequent conflicts. When tribal leaders gain state positions, tribes align with broader political structures. Yet, as the state weakens, tribes inherit political and economic power, contributing to its decline. Central authorities, like those of Saba’, Salihid, Rasulid, Qasimi, and the Yemeni Republic, rarely held full control over the levers of power. Instead, there were marginal or internal entities that nominally adhered to the central state yet operated with a degree of autonomy.18 Moreover, the prominence of tribal powers, which governed their regions with tacit approval from the central state, underscores a persistent theme in Yemen’s political history: the dual nature of authority. Alongside the state’s power, tribal authority always played a significant role.19

Tribal traits differ by region. In inland areas where the Zaidi doctrine began, like the northernmost regions, tribal loyalty is stronger, and, contrastingly, weaker along the coast and the plains of southern and western Yemen. These differences may stem from the unique economic and relational dynamics of each area.20 The southern part of northern Yemen, with its weaker tribal bonds, was host to a wide array of competing Yemeni political parties. Conversely, tribal loyalty in the northern highlands was more concentrated, as tribal leaders increasingly sought power and dominance. This possibly explains the greater power historically held by northern highland tribes, as Table 2 illustrates.

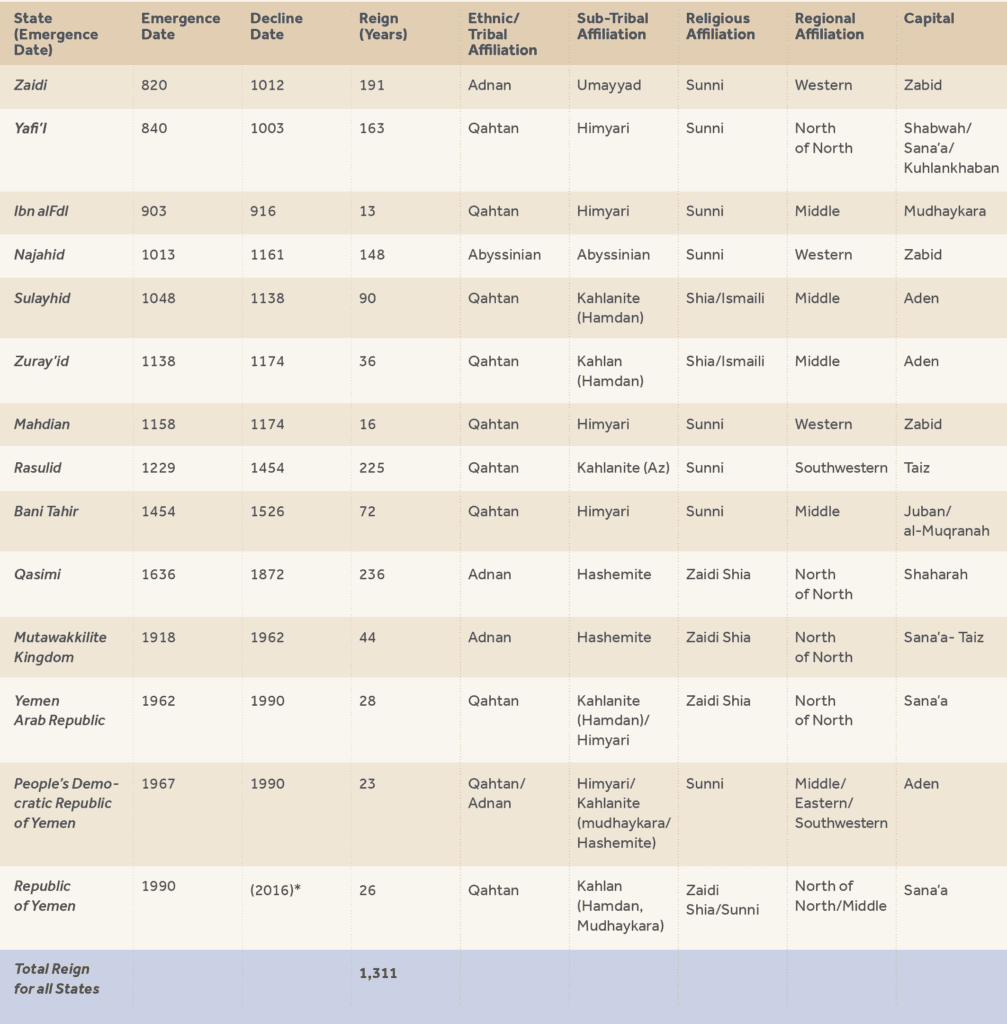

Table 2: Yemen’s Rulers with Tribal, Regional, and Religious Affiliations

*Note: These are the most recent figures in the book on which this table is based.

Source: Adapted from Ahmed Al-Ahssab, Power Identity in Yemen: The Controversy of Politics and History (Al-Za‘ayn, Qatar: Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, 2019).

The table outlines the presence of concurrent power among multiple states throughout Yemeni history, emphasizing shifts in authority at regional, tribal, and doctrinal levels. Notably, the dominant “North of the North” region holds a significant 38% of the total ruling duration across all states. This dominance could suggest that northern highland tribes, due to limited economic resources, viewed ruling as a necessary avenue to wealth. It supports the theory that these highland tribes felt more entitled compared to coastal and plains tribes,21 likely driving their inclination to seize power. Religious sects like Zaidiyyah and Isma’iliyyah often justified one group’s rule over another, resulting in a cycle where factions ousted others from power.

Table 2 also shows that a federal state unifying diverse tribes was absent. Each dominant tribe or group systematically marginalizes others, leading to recurring conflicts and shifts in capital. Economic growth, sectarian tolerance, and tribal leaders’ integration into the political framework prolonged the rule of four states—Zaidiyyah, Ya’afariyyah, Rasuliyyah, and Qasimiyyah. In contrast, other states experienced abbreviated durations in power due to political and sectarian exclusion, internal strife, resource monopolization, and widespread social grievances.

Hence, in Yemen, power has stemmed from the tribe, positioning it as a crucial gateway to governance for both tribal and sectarian entities, regardless of doctrinal differences, as previously mentioned. The prevailing patterns of power acquisition have consistently impeded sustainable governance, resonating with Brian Whitaker’s characterization of Yemen in 2009 as a “land with a long history and a state with a short one.”22

Establishing the Modern State in Yemen and Power-Sharing Collapse

The September 26, 1962 revolution birthed North Yemen’s modern state, and the modern South Yemen state emerged on November 30, 1967. The North was shaped by a traditional elite with tribal ties, while the South was led by a socialist-leaning political elite. Despite the potential for establishing two modern states, both states excessively misused their authority.

Stateless Regime (Fragmented Phase)23

Political elites in fragmented groups monopolized the state’s public arena, concentrating control over violence, the economy, and ideology, which resulted in a stateless system. This regime is a “coalition of forces that is connected by ideological, political, and economic interests and that strives to monopolize power in a social field.”25 To sustain its dominance and grasp on power, it established state institutions for protection and service, driving groups oppressed by its dominance to initially oppose and ultimately resist it.

24 emerged as a mobilization of the aggrieved, with affected groups from diverse tribes or regions actively striving to reproduce the power dynamics should they overcome the existing regime. Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson’s work from 2012 highlights that such a power monopoly subjects the state to violence and political turbulence, making stability or development highly improbable.26

In the southern state, the Marxist-aligned elite initially distributed power and military influence amongst themselves, incorporating tribes into the ruling party. However, over time, internal disputes within the elite gave rise to two factions based on tribal and regional lines, known as “Zumrah”27 and “Tughammah.”28 Each faction monopolized power, violence, and financial resources, to maximize control and sideline other groups. This power struggle culminated in the bloody events of January 13, 1986 that claimed thousands of lives.29 The Tughammah faction ultimately prevailed, but only after the state-building endeavors in South Yemen have failed. This enduring conflict continues to reshape its dynamics and pap of alliances and interests.

In North Yemen, friction emerged between the traditional elite—sheikhs and military figures—and proponents of civilian governance. This unrest led to a coup against the Yemeni Republic’s first president, Abdullah al-Sallal, due to his power monopoly. Post-coup, tribal and sheikh influence in governance surged. A civilian, Judge Abdul Rahman al-Ariani, stood independently with the established presidential council. Nevertheless, Major Ibrahim al-Hamdi spearheaded another coup in the “June 13 Corrective Movement” of 1974.30

Hailing from a family of judges and devoid of tribal backing, al-Hamdi placed his entire reliance on the army, predominantly composed of northern tribesmen, for power retention. His life was abruptly ended by an assassination on October 11, 1977, leading to Ahmed al-Ghashmi’s succession. However, al-Ghashmi’s reign was short-lived—he faced widespread unpopularity and rampant suspicions of al-Hamdi’s murder and was assassinated in June 1978.31

Ali Abdullah Saleh became president on July 17, 1978, after being elected by the Constituent People’s Assembly. He leaned on his Sanhan Hashid tribe to fill governmental positions, manage security, and suppress opposition, favoring his relatives for key positions. He elevated tribal leaders to become state representatives, excluding other regions and political groups from influence and wealth.32

From Unity to the Arab Spring

In 1990, Yemen united, aspiring to democracy and fair elections, yet struggled to fully implement these ideals. A presidential council formed, representing unity partners Ali Abdullah Saleh and Ali Salem al-Beidh, achieving some real power-sharing. However, political wrangling prevailed, necessitating military intervention for unresolved issues. The 1994 summer war resulted in Saleh monopolizing power, ending the power-sharing experiment.

Stephen Day’s 2012 work contends that the 1994 war resulted in reshaping Yemen’s ruling elites, maintaining the political hegemony of northern highland elites, while central and western regional elites oversaw the economy, establishing an informal power balance.33 Over time, the sheikhs of the northern highlands—particularly the Hashid and Bakil tribes—competed with central and western commercial elites, becoming principal beneficiaries of the new political and economic systems.

The 1984 discovery of oil in Yemen led the northern highland elites to revenue exploitation,34 negatively impacting the country as they became regime supporters and undermined development and equitable economic resource distribution. Consequently, regions such as the south, northern north, central, and western areas remained marginalized, fueling the rise of protest movements like the Houthi rebels, the southern movement, and the Tihama and Hadramawt areas—some achieved tangible gains, replicating the state’s exploitative practices.

During his long rule, Saleh established a clientelist system,35 despite superficial representation.36 He exploited elections to consolidate influence, using state resources to strengthen his ruling party. He also utilized wars to eliminate his adversaries and gain economic advantages, thus consolidating power. He established military forces under his family’s command and prolonged the tenure of local and parliamentary councils, obstructing peaceful transitions of power. This bred an opposition—akin to his regime in its monopolistic traits—from sidelined groups, including the Joint Meeting Parties, the Houthi group, the southern movement, and other marginalized resistance factions. These were unlike the underrepresented Tuhami37 and Hadhrami38 movements and other marginalized groups.39

The decline in state revenues at the beginning of the new millennium has strained ties between tribal elites and the regime, undermining state-building and service delivery. The Arab Spring protests in 2011 called for regime change. After around 33 years in power, Saleh ceded power to Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi in 2012.

Transitional or Monopolistic Authority

The consensus signaled by the November 2011 Gulf Initiative40 legitimized Hadi’s ascension to power, mandating power-sharing, presidential elections, and establishing a national unity government over a two-year transitional period. Hadi commenced dismantling his hefty inheritance, consolidating his power by appointing his son as secretary to the president and marginalizing Saleh’s kin and children through diplomatic assignments abroad. He also passively observed the Houthi surge from Saada to Sana’a, mistakenly thinking it would bolster his power and eradicate traditional forces embodied by the Islah party and its tribal affiliates. However, the Houthis revolted, prompting his escape to Aden and subsequently to Riyadh, where he solicited Saudi Arabia’s aid to reinstate legitimacy. This spurred the Saudi-led Arab coalition’s “Operation Decisive Storm” military campaign.

Hadi’s efforts to seize power in a transitional period, amid economic strife and post-Arab Spring recovery, likely exacerbated the state’s fragility by splintering power among warring factions. Hadi, without tangible authority, embodied a puppet regime. As researcher Céline Graczy highlights, “Hadi is well aware that he does not govern Yemen and is being manipulated rather than making choices.”41 On April 7, 2022, after a decade as Yemen’s “Transitional President,” Hadi transferred authority to the Presidential Leadership Council,42 leaving the country entwined in conflict and instability due to his monopolistic pursuits.

Reproduction of Power Monopolization

Saleh’s regime led to the emergence of diverse opposition, from political parties to armed groups like the Houthis and the southern movement. The Houthis engaged in six wars,43 seizing Sana’a in September 2014. Conversely, the Southern Transitional Council adhered to non-violent

political methods, capturing Aden in 2019 with backing from the UAE, despite ensuing armed conflicts with the official government; it was resolved through UAE air raids and Saudi mediation. These two factions represent divergent trajectories of power consolidation in Yemen post-2011.

Ansar Allah: From Resistance to Appropriating Power

Originally a religious movement,44 Ansar Allah, known as the Houthi movement,45 transitioned into armed and political activities, engaging in confrontations with Saleh’s regime from 2004 to 2010, culminating in the six wars. The group eventually seized power on September 21, 2014.46

Initially founded to protect the Zaidi minority, the movement adopted a pragmatic approach in its rise to political and military power. During the 2011 Youth Revolution, the group advocated for the rights of Saada’s residents. In the 2013 National Dialogue, they positioned themselves as the voice of the northern tribes, successfully rallying individual tribespeople—rather than their sheikhs—especially in the northern highlands. Notably, the sheikhs, not the tribes, had reaped the economic and political benefits of the republican system, as mentioned earlier, creating a rift and fomenting discontent that led many tribespeople to align with the Houthis.47 This momentum enabled the Houthis to capture Sana’a, emerging victorious after the Saudi-led intervention in 2015 and propelling them as the representatives of all Yemenis.48

Just as they seized power pragmatically, the Houthis similarly governed with political savvy. Post-takeover, they allied with Saleh,49 initiating the Supreme Political Council on July 28, 2016, with a ten-member even split, chaired by Saleh al-Samad. That year also saw the establishment of the “Rescue Government,” a joint administration.50 However, over the following year, the Houthis started harassing Saleh and his party’s leadership, culminating in Saleh’s assassination on December 4, 2017, leaving the Houthis with unrivaled control.

The Houthis engaged in unprecedented power-grabbing tactics as they centralized power within the Houthi family and their close circles, allocating key military and security roles among them. Furthermore, a “Supervisor System” was founded, led by Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, creating a parallel authority that holds real executive power while existing state institutions’ role became nominal. Predominantly, these supervisors come from the Saada and Hajjah governorates.51

This system allowed the Houthis to infiltrate tribal authority, replacing sheikhs with supervisors who wield absolute regional control.52 The Houthis also established lucrative, independent institutions, such as the General Authority for Zakat, the General Authority for Endowments, and the Supreme Council for Managing and Coordinating Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation.

The Houthis aimed to reshape society according to their group’s identity and narrative. They enforced a Code of Functional Behavior on state employees, mandating the adoption of their ideology.53 They revised educational curricula extensively to align with their beliefs,54 renaming streets, landmarks, and schools in the process. National holidays were sidelined in favor of their specific events and sectarian religious observances, including the anniversary of their seizure of Sana’a and Eid al-Ghadeer.55

The Southern Transitional Council: Reclaiming the Southern State through Power Appropriation

The Southern Transitional Council (STC) was established in Aden on May 11, 2017, led by Aidarous al-Zubaidi and deputy Hani bin Breik, with two additional deputies added recently.56 Originating from active armed factions in the southern movement, STC does not represent all southern factions but lately has sought to negotiate their inclusion to become the sole advocate for the southern cause.57

The primary objective of the STC is to reunify southern Yemen along pre-1990 lines. It seized Aden, the temporary capital, in August 2019 following conflicts with internationally recognized government forces, and later extended control to Dhalea, Lahij, and Shabwa, jointly controlling parts of Abyan with the government.58

The rise of STC to power indicates that the historical conflict between the “Zurmah” and “Taghama” is reemerging, as the majority of STC’s prominent leaders and fighters hail from Dhalea and Lahij.59 In contrast, leaders from Abyan, Shabwa, and Hadramout hold less significant positions.

Culturally, the STC prohibited the display of the unity flag and national anthem in schools, substituting them with symbols of the previous southern state. It promoted activities and lectures emphasizing southern independence and depicted the North as an occupier.60 Economically, STC leadership established its trade elite, monopolizing oil imports and by-products through Aden. One leader highlighted their emulation of the Egyptian army’s economic strategy of asserting dominance across sectors, levying around $15 on every 200,000 tons of monthly fuel imports and controlling roughly 20% of these imports.61

Other southern factions from Hadramout, Mahra, Shabwah, Abyan, and beyond are wary of aligning with the STC under these conditions. Although many notable southern figures back secession, they fear the STC’s dominance, noting its previous exclusionary tactics. As a result, calls for power-sharing, justice, and equality appear to be leveraging strategies for STC expansion.

Peace for Ending the War or for Seizing Power?

Yemen experienced a ceasefire from April to October 2, 2022, resulting in a stalemate at the battlefronts and a flurry of political negotiations. These talks, however, are unfolding with little regard for historical lessons—conflicting parties use them to consolidate power, entrench authority, and expand into oil-rich provinces. The Houthi group is targeting Marib—evident from the Houthi military mobilization62—while STC aims to dominate Shabwah and Hadramout. The sole clear gain has been prisoner and detainee exchanges, but Yemen remains on the cusp of resumed war.

For example, after participating in the National Dialogue Conference, the Houthis overruled its results through the Partnership and Peace Agreement in September 2014, later reneging on its terms to seize control of state institutions. This trend continued in the UN-sponsored international peace talks, which only enabled greater power consolidation and estrangement from imminent partnership. Furthermore, the 2019 Riyadh Agreement between the internationally recognized government and STC hit a snag following the latter group’s power-grab in Aden and nearby areas.

Possible Solutions

Since inception, Yemen’s inherently decentralized power structure has conflicted with attempts to impose the formula of the modern state. The early 20th century Ottomans failed to impose centralized governance in northern Yemen, while British colonists in the South opted to influence local sultans over establishing centralized rule. Subsequent attempts to centralize governance in divided Yemen resulted in power appropriation, fueling further conflict.

A political solution in Yemen, therefore, must embrace decentralization to mitigate monopolies of power. Given current conflict dynamics, federalism or decentralized governance emerge as fitting solutions.

Federal Yemen

By the late 20th century, more countries adopted federal systems tailored to their unique environments and societal cultures. Ethiopia in 1991 is a prime example, having embraced federalism to address ethnic divisions from its tumultuous history.63 In 2013, Yemen’s National Dialogue also endorsed federalism, proposing three governance levels: federal, regional, and local.64 Participants deemed this structure a potential fit for the country. However, while there was consensus, disagreements arose concerning the number of regions. The initial proposal suggested six regions (four in the north, two in the south), but the southern delegates demanded a simpler, two-region division (north and south). The Houthis rejected the division plan, saying it was divided politically, rather than administratively as President Hadi. This disagreement was among the secondary factors that propelled the Houthi takeover in 2014, leading to the suspension of the National Dialogue’s outcomes.

This history raises the question of the efficacy of a federal system as a potential solution to power-sharing difficulties. Some see it as promoting power-sharing and equitable wealth distribution, but others fret about potential fragmentation and oil-rich regions overshadowing their less affluent counterparts, potentially igniting wealth-related conflicts. Additionally, fears of power-grabbing and appropriation of resources on both the national and regional levels are evident, given that each region encompasses various provinces with diverse tribal affiliations, raising concerns about potential tribal dominance in certain regions.

The war exacerbates these concerns, creating a divided political and military landscape that mirrors a regional setup. The Houthi hold in the north (excluding Marib and Taiz) and STC influence in the south illustrate this. Yemen’s history, as discussed in the first part of this paper, suggests that a federal system could solidify existing autonomous powers, legitimizing them with official governance, legislative, and military structures. This system risks exacerbating fragmentation, perpetuating conflict, and allowing constant foreign intervention to mediate between disputing regions. Consequently, federalism offers little to solve power monopolization; it potentially redistributes power from the central to the regional level, producing a precarious peace.

Decentralized Governance

Decentralized governance might not be a good fit for Yemen, yet it emerges as a preferable strategy to curbing the monopolization of power. A prevailing theory suggests that augmenting local council powers correlates with an increase in the efficacy of service delivery to citizens.65 Research highlights that successful local governance exhibits innovation, adaptability, and creativity.65

Moreover, decentralization is recognized as an effective means to manage and resolve conflict. For decades, it has been the go-to option for international organizations aiming to reform governance systems.67 This preference establishes mechanisms that distribute power among competing factions and guarantee citizen engagement in local policymaking.

Decentralized governance offers a distinct alternative to federalism. Decentralized governance lacks extensive powers across various governance levels and limits comprehensive authority for regions. This approach aligns more closely with Yemen’s historical duality in governance and social structure.

Decentralization is not new to Yemeni elites and the populace, in contrast with the less familiar federal system. Despite adopting the principle of decentralized governance after the 1990 unification, its implementation only began a decade later under the 1994 constitution.68

The early 2000s saw Yemen’s first local council elections.69 However, Saleh’s regime reduced these councils to nominal entities. Yet, the current war’s resultant political and security vacuum has enabled local authorities in regions under the internationally recognized government to exert more influence. In Hadhramaut and Marib, authorities have successfully allocated 20% of oil and gas revenues to development initiatives,70with Marib experiencing significant growth—a change from less than 1% prior to 2015.71 The recent establishment of the National Hadhramaut Council72 further bolsters the province’s self-governance.

Decentralized governance is a foundational principle for conflict resolution. Applying this system in Yemen would entail integrating the Houthi group into the Presidential Leadership Council to establish a broad-based, technocratic, central government—paralleling the expanded, self-governing local councils in Marib and Hadhramaut—and setting a clear trajectory towards decentralization.

However, this approach may encounter hurdles, such as economic resource distribution. A viable solution involves forming a national economic committee; incorporating economic experts from various factions under international oversight; ensuring equitable economic resource allocation; boosting local development; increasing transparency; and curbing exploitative practices.

The second challenge is STC’s demand for independence for the South and its joint opposition, with the Houthi group, to decentralized governance. Currently, the South implicitly operates under decentralized governance—Aden, Dhalea, and Lahij under STC administration, and Abyan, Shabwa, Hadhramaut, and Mahra under varying levels of local governance. Strengthening local councils could curb STC power and wealth and also diminish the Houthi group’s stronghold in the North.

It is crucial to acknowledge the risky implementation of top-down decentralization, as it might result in a specific elite seizing power. Thus, establishing successful decentralization requires a holistic, bottom-up approach that incorporates input from all political elites, civil society, and regional support. Utilizing the “National Strategy for Local Governance”73 is recommended, as it clearly defines the mechanisms for decentralized governance and ensures equitable resource distribution.

Recommendations

This paper concludes by outlining suggestions for stakeholders capable of altering Yemen’s power dynamics.

Firstly, for local actors:

- Acknowledge that power-sharing, tolerance, and implicit decentralization are crucial for stability and development. Yemen’s historical states thrived on these principles, which are absent in today’s conflict.

- Be ready to compromise for a comprehensive political settlement. The present circumstances, with each faction engaging in power-grabbing, hinder such a resolution. A settlement without mutual concessions risks legitimizing military gains and promoting instability.

- Empower local councils, along with the internationally recognized government and the Houthi movement, to emulate the Marib and Hadramout models at provincial and district levels. This would grant them more autonomy in resource management, revenue distribution, and service provision and facilitate direct partnerships with international donors.

- Establish a national economic committee, incorporating experts from all factions, to guarantee equitable economic resource distribution.

- Revisit the National Dialogue Conference outcomes, opting for a governance model grounded in decentralization or contemplating integration using a federal system. Of the two political systems, decentralization is most suitable to Yemen’s social fabric and historical narrative.

Regarding the actively involved regional states, it is imperative that they:

- Urge local entities to compromise for a political resolution; openly back Yemeni unity; uphold Yemen’s sovereignty over its ports and islands; and abstain from actions that might escalate conflict or extend the war. Additionally, they should not exploit the challenging economic climate to assert control or dominance.

- Strive to consolidate the currency and empower the Yemeni Central Bank, reestablishing it as a pivotal national entity. This involves financially supporting local council budgets, devising a liquidity injection mechanism, and aiding in infrastructure reconstruction.

- Bolster local councils: Avoid backing the creation of alternative entities or parallel councils, which would only weaken local council operations and add complexity to the Yemeni situation.

The international community should:

- Draw lessons from previous transitional period failures, redoubling efforts to ensure the success of potential settlements. This involves focusing on the political process, addressing the economic situation, and initiating a roadmap for early decentralization starting with the transitional phase.

- Advocate for a decentralized political solution: Expand the Presidential Leadership Council to incorporate additional factions and allocate resources via a joint economic committee under international supervision. Local authorities should have autonomy, while maintaining a national identity.

- In international projects—spanning humanitarian, developmental, cultural spheres, etc.—substitute involvement of government bodies, local organizations, or private sector entities with local councils. This bolsters their legitimacy and leverages the decentralized model for service provision.

- Concentrate on fortifying the institutional capacities of local councils from the ground up, specifically the judiciary, security, democracy, and administrative domains. Leveraging international expertise to adopt accountability and transparency mechanisms is crucial.

- Motivate all political, popular, and tribal factions to engage in local governance through local councils, averting exclusion, addressing grievances, and breaking historical patterns of governance.

Endnotes