Iraq’s Development Road Project:

A Path to Prosperity or Instability?

Issue Brief, October 2024

Key Takeaways

A Key Opportunity for Regional Cooperation: Iraq’s Development Road Project provides a driver for economic prosperity that could benefit the entire region, tapping into synergies and connectivity with existing ports and infrastructure.

Iraq’s Disorderly Politics Present Challenges: For it to work, Türkiye and the Project’s Gulf signatories need to ensure that Iraq can get its political house in order. The exclusion of the Kurdistan region from the Development Road does not bode well for its sustainability.

GCC’s Existing Investments are a Litmus Test: Iraq is enjoying improved relations with the GCC and there is a trend in the region toward mutual cooperation, but the Gulf states’ pre-existing economic commitments in Iraq will function as a litmus test for their involvement in the Project.

Coordination can Enhance the Project’s Resilience: Türkiye, the UAE, and Qatar should coordinate their involvement in the Development Road to give them strategic depth and ensure the Project is resilient to Iraq’s volatile political environment.

Introduction

Iraq’s Development Road Project constitutes a bold and much-needed initiative for a country that has been plagued by decades of civil war, ethnic and religious conflict, and geopolitical tensions. The $17 billion Development Road Project (hereafter referred to as Development Road or the Project) aims to transform Iraq into a transport hub by connecting its southern hinterlands to the Turkish border in the north,1 and act as a major driver of economic prosperity in both Iraq and the wider region.

The Development Road forms part of a wider trend of regional economic integration initiatives that have played an important role in de-escalating regional tensions. Iraq, Türkiye, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are all stakeholders and signatories to the Project. The involvement of both Doha and Abu Dhabi is notable, because it highlights the warming of ties within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) since the 2017 crisis between Qatar and its neighbors came to an end in 2021.2 It also highlights Baghdad’s deepening economic and geopolitical ties with the Gulf states in recent years.3

There are a multitude of geopolitical layers that will be central to the Project’s success, in addition to navigating a volatile political environment in Iraq and the country’s potential for conflict relapse. While Türkiye shares wide-ranging economic and security interests with Iraq, and is playing a leading role in the Project, Ankara’s role in the Development Road will not be without challenges. Turkish bases have come under attack by the Iranian-backed Popular Mobilization Force (PMF) and Türkiye is currently conducting a military campaign against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in northern Iraq.4 Iran, which is not included in the Project, has also expressed concerns over the Project and has the potential to undermine the Development Road through its allies in Iraq.

Against this backdrop, this issue brief outlines the challenges facing the Development Road. Although Qatar and the UAE will be important enablers of the Project as geostrategic partners and economic powerhouses, the pathway to success will be predominantly determined by Türkiye and Iraq. Türkiye’s long-term involvement will be crucial to securing Qatar and the UAE as economically vested partners. Türkiye is also a powerful actor within the Iraqi political and economic landscape and provides the linkage between Asia and Europe, which is a fundamental component of the Project. Although Türkiye harbors concerns toward the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC),5 which intends to bypass its territory, Ankara’s leading role in the Development Road will determine whether the latter will rival or supplement IMEC. Türkiye’s role will also determine the extent to which the Development Road will augment and enable China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).6 These dynamics highlight the geopolitical significance of the Development Road.

This issue brief also warns of several other geopolitical and domestic dynamics that must be addressed for the Project to succeed. This includes the contentious status of the PKK’s presence in Iraq, tensions between Erbil and Baghdad, and the potential spoiler role that the PMF could play, in addition to wider geopolitical concerns, since the Project could undermine the economic and geostrategic interests of Iran and Kuwait.

Linking Asia to Europe

The Development Road aims to shorten the travel time between Asia and Europe, by linking Basra, Iraq, to Ovaköy, Türkiye, and joins the BRI and IMEC as a major regional economic integration initiative.7 These ambitious projects have received much media attention but have lacked details. However, the Development Road is strongly positioned to come to fruition because it forms an essential part of Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani’s domestic and geopolitical agenda, as well as constituting an amalgamation and consolidation of several infrastructure projects that are already in progress.8 This includes logistics hubs, industrial complexes, and the integration of oil and gas pipelines.9

Unlike the BRI and the IMEC, which are rival global initiatives, the Development Road is an Iraq-centric undertaking, focused on existing infrastructure projects and aimed at turning Iraq into a major transit country and infrastructure hub to enhance its strategic and economic position.10 The realization of its objectives and ambitions are, therefore, more realistic. Moreover, while the Development Road could require Qatar and the UAE as committed investors, it ultimately relies on the leadership of Iraq and Türkiye rather than a whole host of governments, as is the case with the IMEC –– whose stakeholders have not taken ownership over its implementation.

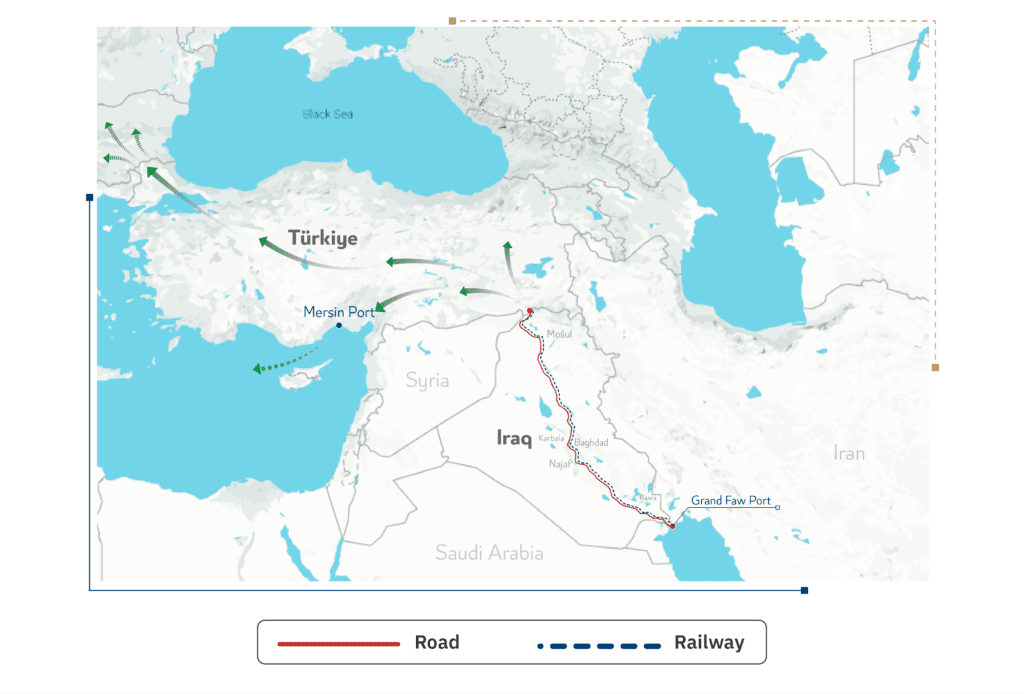

The Development Road could be an enabler of both the BRI and IMEC, since it is centered on Iraq’s geographic position, its geopolitical relations, and its ongoing infrastructure development. The most crucial component of the Development Road is the Grand Faw Port, which will enhance Iraq’s ability to receive larger container ships and reduce its dependency on the nearby Umm Qasr port. Announced in 2010 and launched in 2013, the Grand Faw Port project constitutes the southern terminal of the Development Road and is expected to be concluded in 2028 –– the first of the Project’s three phases. The 1,200-kilometer road and rail Development Road would connect Faw in Basra to Faysh Khabur on the border between Iraq and Türkiye, before connecting to Türkiye’s rail and road network.11 The venture is meant to provide access to the Mediterranean Sea via the Turkish port of Mersin and reach Europe by road via Istanbul.12

The Project as a whole is scheduled for completion by 2050.13 Faw port, which was delayed as a result of financial challenges and the war on the Islamic State,14 will be able to receive the world’s largest container ships, with an expected 99 berths, making it the largest port in the Middle East.15 By 2028, the port is expected to handle 36 million tons of containerized freight and 22 million tons of dry bulk, unpackaged goods that are transported in large standardized containers. The plan is to further increase these numbers by 2038.16

Iraq Development Road – Map 17

Succeeding where Others have Failed?

Under Sudani, the Faw Port and Development Road have been identified as national priorities. However, the Project is riddled with significant challenges. Iraq’s previous prime ministers have attempted to develop ports and other large infrastructure projects which have envisioned large-scale changes to Iraq’s transport infrastructure, but progress has slowed and stalled because of conflict and political volatility.18 Outside of Turkish and Iraqi enthusiasm, there has been a cautious posture from Qatar and the UAE.19 Indeed, it is up to Baghdad and Ankara to prove the Project will not succumb to domestic and regional pressures like those before it.

Several factors work in Baghdad’s favor. Regionally, there is a trend toward cooperation and de-escalation. There is also a greater appetite among the Gulf states to become proactive players in Iraq. The UAE is expanding its footprint through Dana Gas and Crescent Petroleum by securing contracts to develop gas fields in the south, building on its long-standing presence in the Kurdistan region.20 Saudi Arabia is making inroads by investing in Anbar and a number of other projects, including an electricity link with Iraq as part of the GCC Interconnection Authority (GCCIA).21 Qatar has a 25% stake in the $27 billion Gas Growth Integrated Project (GGIP).22 Estithmar Holding has also committed $7 billion to real estate and tourism development in Baghdad.23

Iraq is thus renewing its relations with Türkiye and the Gulf countries. Türkiye has an impressive, multi-layered network in Iraq, with significant influence in the Kurdistan region, the Arab Sunni north, and patches of Baghdad and the south. In 2023, Türkiye’s bilateral trade with Iraq totaled $19.9 billion.24 During the first three months of 2024, Turkish exports to Iraq also grew by 24.5%.25 In March, Iraq and Türkiye agreed to establish a joint operations center aimed at combatting the PKK,26 an unprecedented move since it effectively means Iraq and Türkiye would be working to expel the group from Iraqi territory.

Domestically, Iraq is enjoying a period of stability. Sudani has managed to placate the PMF and has improved Baghdad’s relations with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), despite numerous outstanding issues between them.27 Sudani has also balanced Baghdad’s ties with both Washington and Tehran, despite the violent ramifications of the war in Gaza. Furthermore, a Gallup poll indicated Iraqis’ increasing faith in their political and national institutions, including a record 56% who expressed trust in the Sudani government.28

Yet, this calm could be short-lived, given Iraq’s potential for a relapse into conflict, regional tensions, and the possible return of populist cleric Muqtada al-Sadr to the political fray.29 What could also undermine the Development Road is Iraq’s dependency on oil and lack of economic diversification. Iraq’s foreign reserves are at a record level due to high oil prices, but are vulnerable to oil price shocks and U.S. sanctions.30 Qatar and the UAE could be the Project’s most important investors, but Iraq’s vulnerability to oil prices and failure to dedicate its own resources will limit the scope and scale of investment from Abu Dhabi and Doha, who may first need to see Iraq prove its own commitment through deeds, and not just words.

The dependency on oil also has direct implications for socio-political stability. Iraq’s population is rapidly growing: it has surged from 27 million in 2003 to 40 million today, with projections suggesting it could top 50 million within the next 10 years.31 This will exert strain on the government’s ability to expand the public sector and employ the 700,000 Iraqis that graduate each year.32 Iraq’s youth bulge risks adding to an increasingly discontented and disenfranchised population. These socio-political dynamics will shape the political and security climate in the years to come and could, therefore, determine the fate of the Development Road.

The rivalry between powerful factions of the Shiite political class adds an additional hurdle. Foreign companies have had to manage such rivalries, as in the case of South Korea’s Daewoo, which was awarded the contract to develop the Grand Faw Project but had to stave off pushback from Asaib Ahl al-Haq, which was in favor of a Chinese company.33 These tensions warrant attention, since economic prominence translates into patronage networks and political influence. Iraq’s southern ports are rife with corruption and the dominance of Iran-aligned groups. These groups dominate the customs department, supervise the security of the area and divert billions of dollars away from Iraq’s coffers.34 Given the scale of the Development Road, there is likely to be an escalation in factional disputes if a long-term settlement is not reached.35

The Turkish Lynchpin: Managing Disruptions

In theory, Iraq’s security challenges should not prevent the Project from coming to fruition. While both the PKK and the PMF have a track record of sabotaging infrastructure and commerce,36 much like ISIS and its ilk,37 Iraq can manage and contain these challenges. For example, attacks on hydrocarbons infrastructure can be mitigated with security controls, including pipeline fortification methods and the deployment of security personnel. This explains why such attacks have been intermittent and of limited consequence.38

This bodes well for encouraging foreign investment, which is also helped by the ongoing support Iraq receives from the United States in combatting terrorism. International investors have not been completely deterred from operating in a frontier market, which has the world’s fifth-largest proven oil reserves,39 and are encouraged by the fact that Iraq continues to receive support from Washington.40 Moreover, despite security challenges, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE are also increasing their economic footprint in Iraq. Similarly, China’s direct investments in Iraq amounted to $34 billion in 2023, making it the largest investor in Iraq.41 These are encouraging indicators for a country that has suffered two civil wars over the past decade.

That said, there are other contextual challenges. Attacks on Turkish bases and personnel have escalated in response to Ankara’s incursions into northern Iraq against the PKK. The PKK has established affiliates and has ambitions to turn the territory it controls into a self-governing canton, which represents a direct threat to Türkiye’s national security interests. Moreover, Türkiye has been accused by Iraq of weaponizing water supplies.42 The Project’s infrastructure could also be vulnerable in Faysh Khabur, which straddles the Türkiye-Iraq-Syria border and is regularly shelled by Türkiye.43 The area constitutes a strategic crossing for the PKK and, to complicate matters, U.S. forces stationed in north-eastern Syria depend on a ground supply line via the area.44

Tensions between Baghdad and the KRG, which controls Faysh Khabur, also have implications for Türkiye’s long-term involvement in the Project. Apart for the last 15 kilometers near the border with Türkiye, the Development Road lies outside of the Kurdistan region.45 The exclusion of the KRG has prompted Erbil to revive its efforts to build a railway that would connect Iran and Türkiye through territory it governs, which is unfolding against the backdrop of improved ties between the KRG and both Iran and Türkiye.46 Despite Erbil-Baghdad tensions, this could serve as a win-win for both governments, augmenting the Development Road by establishing an additional economic integration initiative that includes two regional heavyweights.

Iraq could bank on Türkiye’s willingness to bypass the KRG. However, such a move would be a gamble. Türkiye has a historic relationship with the KRG that renders the latter an important pillar of Ankara’s regional geopolitical and security interests. Türkiye has historically drawn on this relationship to enhance its influence and leverage in Iraq. This included a historic 50-year accord in 2014 that has been central to the economic empowerment and autonomy of the KRG and to the KRG’s emergence as a pillar of Türkiye’s geostrategic interests.47

Although the Kurdish independence referendum in 2017 strained relations between Türkiye and Iraq, they have since been repaired.48 Iraq must appreciate that Türkiye’s national security imperatives are intertwined with the long-term political standing of the KRG and its ability to contain the PKK on both Kurdish and Iraqi territory. That, in turn, creates interdependence and interconnectivity between Türkiye’s ongoing tensions with Baghdad––including over water and the PKK—and Baghdad’s relations and disputes with the KRG. Although there are a number of challenges facing Türkiye and Iraq, these are manageable and can be mitigated. However, rather than merely papering the cracks, it is important that they are addressed to ensure there are no consequential implications for the Project.

The GCC & The Iranian Elephant in the Room

There has been a marked improvement in Iraq’s relations with the GCC. The Gulf states have sizeable investments and commitments in Iraq and these ties could become a litmus test for their involvement in the Development Road. It is inconceivable that Doha or Abu Dhabi would fulfil their commitments to the Project unless their pre-existing economic engagements in Iraq live up to their expectations.

For the foreseeable future, the Gulf signatories to the Project, as well as Türkiye, will keep a close eye on whether Iraq is able to get its house in order. In addition to Erbil-Baghdad relations, that also requires improved relations between Baghdad’s Shiite ruling elite and the Arab Sunni community, including its political leaders, such as Mohammed al-Halbousi and Khamis al-Khanjar. Cross-sectarian coalition-building efforts have helped improve these relations and, therefore, Iraq’s ties to Türkiye and the Gulf states.49 Khanjar and Halbousi have strong ties to the UAE, Qatar, and Türkiye.50 Geopolitically, the state of relations between the Arab Sunni political elite and the ruling Shiite political class will likely shape the scope and scale of GCC involvement in the Project, in much the same way as GCC engagement with Iraq was shaped (and limited) by the sectarian policies of previous Iraqi administrations.51

In the same vein, Iran has not been included in the Project, but it is inconceivable that Tehran and its allies in Iraq would play no role, which could challenge the materialization of the Development Road. While the Project has strategic importance for Iraq and its partners, it is premised on long-term regional cooperation. Iran and its allies will be watching closely to assess whether the initiative threatens to change the balance of power in Iraq and may move to prevent the Project from coming to fruition to ensure there are no second and third-order effects that undermine Tehran’s influence.

Iranian officials have already expressed concerns that the development of port infrastructure presents a geostrategic and commercial threat.52 The development of both Umm Qasr and Faw, and the wider geostrategic aspirations of the Project, could diminish Iran’s own economic standing since Iran’s ports are already competing with the UAE’s Fujairah and Jebel Ali.53 In the long term, Iran will keep one eye on ensuring the ports do not serve as a base for hostile foreign forces. Tehran may see the Project as one large step toward enabling a Türkiye and GCC-aligned sphere of influence, including the emergence of an autonomous Sunni region.54

Iran has a proven ability and willingness to use its political strength in Iraq to push back against strategically significant initiatives and could use its influence within the Iraqi parliament and Supreme Court to torpedo the Development Road.55 It is precisely in this context that Türkiye will have to take on the mantle of regional leadership, rather than leaving the fate of the Project to long-running geopolitical tensions. This includes reassuring its GCC allies that the Project can succeed, working with its partners and allies in Iraq to address Iran’s concerns, and building a national consensus around the Project.

However, it is not just Iran that could see the Project as a threat. Iraq and Kuwait were previously embroiled in a dispute over the construction of the Mubarak Al-Kabeer Port on Bubiyan Island, just kilometers away from the Iraqi coast, which Baghdad fears could undermine the Umm Qasr and al-Faw ports.56 Construction of the Kuwaiti port had been paused for ten years until it was revived earlier this year, with some suggesting this was partly motivated by Iraq’s plans to build Faw and the wider Development Road.57

Conclusion

Several challenges lie in the way of the Development Road. Iraq suffers from widespread corruption, the risk of conflict relapse, and the dominance of armed groups that have an outsized say over the future of major infrastructure projects. The ambitious scope and scale of the Project stands out because it relies on the cooperation and support of Iraq’s neighbors. As a result, a number of geopolitical and domestic dynamics must work in Iraq’s favor for the Project to materialize.

The onus is on Iraq to spearhead the successful implementation of the Project. However, Türkiye’s involvement as a leading partner can help mitigate the geopolitical challenges the Project faces. Türkiye’s credibility as a regional power will be tested, as will Iraq’s ability to assuage the concerns of its neighbors. Prime Minister Sudani will need to continue to placate the PMF and Iran without undermining the Project or alienating its regional stakeholders. This will also require clearly communicating the role of the Gulf states in the Project, identifying key areas of contention or red lines, and establishing consensus amongst rival groups such as Asaib ahl al-Haq and the Sadrists.

Iraq could use the Project as an arena for mutual regional cooperation, as well as for balancing its relations with the United States, China, and other powers by finding synergies and connectivity between the Project and existing regional infrastructure. For the United States, the Development Road provides alternative trade and supply routes in a region where such conduits are under increasing pressure, as highlighted by Houthi attacks on shipping in the Red Sea. For China, the Project could enhance, rather than undermine, the BRI. To ameliorate Kuwait and Iran’s concerns, a plausible case can be made for the Development Road as a complement to Kuwaiti and Iranian ports and infrastructure. The Development Road would enable an integrated and efficient network that improves trade flows, opens up opportunities for collaborative initiatives among regional private and public sector entities, reduces bottlenecks, and enhances the resilience of regional trade.

Türkiye, Qatar, and the UAE could also develop back-channel dispute resolution mechanisms to ensure their investments in the Project are protected by arbitration clauses and bilateral investment treaties. This means creating dedicated channels to both the Prime Minister and the PMF to ensure the Project progresses smoothly, and to mitigate challenges if and when they arise. The Gulf states have pre-existing economic commitments in Iraq that will function as litmus tests for the GCC’s involvement in the Project. Securing deliverables on the GCC’s investments will therefore add regional momentum to the Project. Moreover, Türkiye, the UAE, and Qatar should coordinate their involvement in the Project to avoid confliction, unify their messaging, and secure the Project’s viability in the long run.

Although militias dominate key strategic infrastructure in Iraq, the dominance of armed groups at the ports is tied to the rivalry between the Sadrists and Asaib ahl al-Haq. The challenge for Baghdad is to manage this rivalry and find a settlement that allows the Development Road to materialize. In this context, the exclusion of the KRG from the Project does not bode well for the Project’s sustainability. Kurdistan is a key geopolitical intersection and a key player in Iraq. That means the exclusion of the KRG will at best diminish support and investments from the GCC and Türkiye, and at worst derail the Project completely.

Türkiye, Qatar, and the UAE should condition their commitment to the Project on the inclusion of the KRG. Similarly, genuine commitments are needed from Baghdad that the Project will not unduly empower and prioritize businesses, local investors, and communities that have strong ties to the Shiite political class and powerful Shiite armed groups, lest the Project succumbs to Iraq’s long-running sectarian divisions and tensions or marginalizes and alienates minority communities.