AI Competition amid Expansion of U.S. AI Chip

Export Controls into the Gulf

Issue Brief, June 2024

Key Takeaways

National Security Concerns and Risks from Frontier AI: In the United States, East Asia, and Europe, supply chain considerations have brought industrial policy back to the semiconductor industry. Gulf states need to be aware of these geopolitical risks, given the exacerbating U.S.-China tensions.

Set Concrete AI Regulations to Mitigate Risks: Bearing in mind artificial intelligence (AI) chips would be deployed to a plethora of dual-use technologies, Gulf states need to be equipped with jurisdiction-led, updated data laws and new AI regulations for implementation.

Supply Chain Role in an Era of Proliferating Export Controls: Achieving semiconductor self-sufficiency is unlikely in the Gulf, given the global development and competition challenges. However, they should identify a role to play in the chip supply chain, in tandem with reinforced research and development (R&D) on 6G connectivity.

Policy Roadmap for AI Chips: Given the inevitability that a choice must be made between the U.S. and China, Gulf states should establish a full-fledged roadmap for a clear policy direction in AI chips as a source of economic diversification.

What AI Chips Mean for the Gulf: An Indispensable Source for a Digital Path

The release of open-source software, OpenAI’s “ChatGPT,” at the end of November 2022 signaled the dawn of an era in generative artificial intelligence (AI) based on large language models (LLM). It prompted governments and businesses around the world to develop their own LLM for sovereign AI. LLM operations require advanced chips for processing—e.g., Nvidia’s graphic processing units (GPUs), such as H1001—and memory—e.g., SK Hynix’s high bandwidth memory (HBM), such as HBM3E.2 Nvidia’s stock rally following the company’s post of revenue earnings in March 2024 and subsequently in May 20243 attested to the advent of the AI revolution.4 Nvidia’s market valuation confirmed that “chips are the new oil”.5 Nvidia soon became the third largest company in the world, valued at $2.6 trillion as of May 2024,6 surpassing Saudi Aramco and trailing only Microsoft and Apple.7

The fossil-fuel-reliant Gulf states—mainly Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—look toward the chip industry and AI to diversify their economies via digitization. Saudi Arabia,8 the UAE,9 and Qatar10 call for digitization and AI in their national strategies for this purpose, albeit in varying degrees of emphasis. In recent years, Saudi and Emirati maneuvers in this sector—notably that of the UAE—acknowledge that investment in semiconductors is crucial for full-fledged digitization through AI implementation,11 as chips are essential ingredients for digital infrastructure,12 The two Gulf states have thus far had intensive partnerships with Chinese institutions and engineers concerning AI development, prompting the United States (U.S.) to scrutinize their own cooperative mechanisms with the region.13 Such scrutiny comes at a time when U.S. export controls on semiconductors and chip-producing materials and equipment against China14 have expanded.15 These control measures extend to the Gulf.

This issue brief investigates the rapid development of AI in the Gulf amid the intensifying U.S.-China tech war. It focuses on AI chip export controls and the development of LLMs in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Building on this context, the brief calls for filling in the missing planning pieces in the Gulf, while navigating the U.S.-China geopolitical tensions, being aware of the industry and supply chain potentials, and setting an AI legalization and updated data governance.

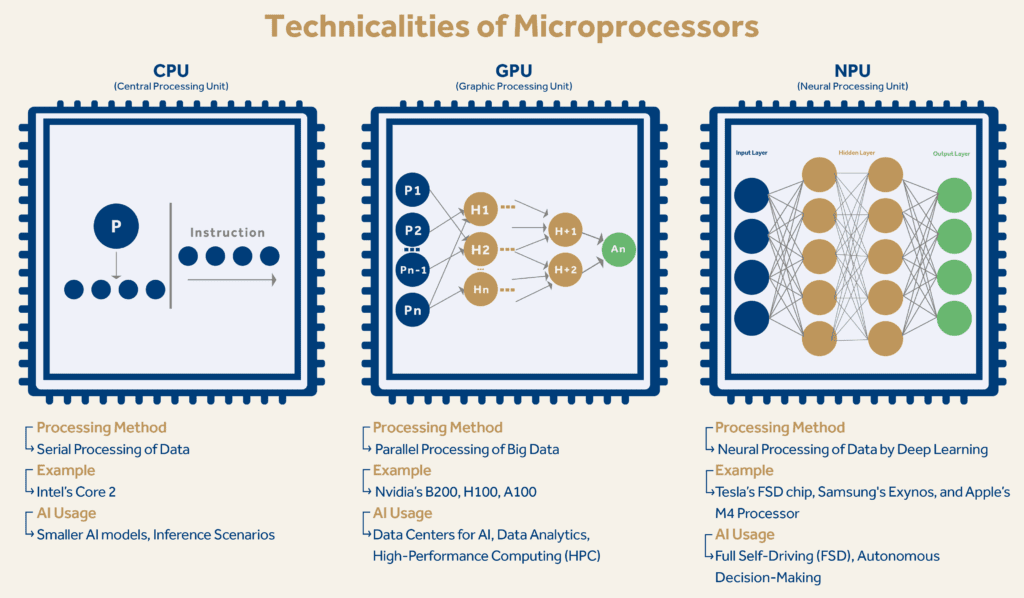

As the AI revolution proliferates across the globe, the trade in the components needed for its development—GPUs and HBMs for generative AI and neural processing units (NPUs) going forward—are highly likely to be further restricted by the U.S. in its technological competition with China. The U.S. is expanding these curbs based on national security concerns and market share over AI supremacy. The Gulf states are also likely to be impacted by the U.S.-China tech war and it is highly anticipated that these tensions would continue and worsen in the near future.16

AI in the Gulf: U.S. Export Controls, LLMs, and AI Chips

Since 2020, tensions between the U.S. and China have led to the deployment of export controls by the U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) under the Biden administration—the first was put in place on October 7, 2022,17 and the second was enacted on October 17, 2023.18 Meanwhile, with the CHIPS and Science Act, the U.S. government lifted its taboo on industrial policy and provided up to $52 billion in government subsidies to foster chip manufacturing and research and development (R&D) within the U.S.19 The end game of the U.S.-China tech war is in the supremacy of AI, pertaining to geoeconomics—global market shares and leadership in industrial revolution—as well as geopolitics—military AI applications for cyber warfare.

Prior to the BIS export controls under the Biden administration, the Trump administration banned the export of a range of fifth-generation- (5G-) related chips to Huawei, a Chinese telecommunications company. As much as the sixth generation (6G) development and connectivity would be required for seamless AI implementation, export controls on AI chips, such as GPUs and HBMs that are included in GPUs, and subsequent chip development for AI, such as NPUs, would likely continue and perhaps even accelerate. All the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) economies were included in the U.S. chip export controls as of October 17, 2023, under country group D:4 (Missile Technology).20

Amid the AI boom, the Gulf states have been proactive in AI development in their own jurisdictions. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are core investors in chip industries and AI to construct AI designed for their interests,21 as in the “sovereign AI” emphasized by Nvidia’s CEO Jensen Huang.22 That said, because these two countries are mainly end-users of chip technology, rather than producers of materials or equipment for chip production, the policy impact of the U.S. chip export controls is less understood in the two Gulf states. Indeed, these U.S. controls and industrial policy have an effect, particularly in East Asia and Europe, on the chip supply chain in all its production steps, from design to materials to equipment, which also affect the Gulf.23

Impact of U.S. Semiconductor Industrial Policy and Export Controls on the Gulf

The initial edition of U.S. export controls on semiconductors were announced on October 7, 2022.24 Measures on Dutch and Japanese semiconductor equipment followed in March 2023.25 Advanced chips such as Nvidia’s GPUs (A100 and H100 chips) were included in the second edition of BIS export controls on October 17, 2023,26 to curb China’s access to advanced chips. While AI chips developed by tech companies in-house have yet to come under U.S. export control scrutiny as in the case of Rain Neuromorphics27 by Sam Altman,28 it is expected that China’s cyber industrial espionage to circumvent chip export controls will increase. The case of cyber-attacks on the Dutch lithography machine producer, Advanced Semiconductor Materials Lithography (ASML), whose extreme ultraviolet (EUV) machinery are under U.S. export controls are a case in point.29

In August 2023, Nvidia revealed that the U.S. government has demanded additional licensing requirements for exports to some countries in the Middle East.30 At the time, the main parties at risk of losing access to AI chips if licenses were not granted by BIS were presumed to be Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The Kingdom had purchased at least 3,000 units of Nvidia’s most formidable GPUs, the H100 chips,31 at $40,000 a piece, while the UAE had secured thousands of Nvidia chips.32 Following Nvidia’s U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings, BIS curbed the export of the H100 and A100 chips to China in October 2023. The Gulf countries were also embedded in those controls as part of Country Group D:4.33 The main countries of the Gulf targeted for chip export controls by the U.S. government are Saudi Arabia and the UAE, though Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait, and Qatar are also part of Country Group D:4.34 In a recent deal, Qatar’s Ooredoo secured Nvidia chips for Ooredoo data center operations in Qatar, Algeria, Tunisia, Oman, Kuwait, and the Maldives.

In previous years, the Gulf region had embraced Huawei’s 5G equipment, despite the Huawei ban under the Trump administration, which called on partners to voluntarily collaborate at the time. The more recent export controls under BIS regulations, however, carry teeth. These controls are intended to alter the entire global supply chain of semiconductors and are imposed to block China’s access to advanced chips and stalling its ascendancy in chip technology and AI supremacy—albeit questions regarding the efficacy of the controls.35 For the Gulf, the controls present a particular risk to the region as they are working closely with China on AI. If such controls are extended to the Gulf for fear of inadvertently aiding China’s AI chip development, then this will stunt AI development in the Gulf.

The consequences of the intensifying U.S.-China tech conflict may be even greater for the Gulf states, as future industries in the region depend on purchasing advanced semiconductors.36 Saudi and Emirati roles in the ecosystem have so far been limited to providing the required capital to secure advanced chips. As the geopolitical rivalry intensifies, this may not be enough.

There are indeed intentions to foster indigenous semiconductor R&D and fabrication in Saudi Arabia37 and the UAE, but the foreign parties involved are not major players in the global semiconductor industry.38 With the exception of Mubadala39 holding majority shares in GlobalFoundries, the role of the two states is limited to being end-users of semiconductor production. The high barriers of entry into foundry business reveal how challenging it is to bring semiconductor production into a jurisdiction with capital alone—even if electricity, land, and water are plentiful—without a solid ecosystem encompassing knowledge and talent.

LLMs in Saudi Arabia and UAE and AI Regulations

In Saudi Arabia, the Saudi Data and AI Authority (SDAIA)40 launched the center for generative AI with Nvidia41 and a pilot version of the Arabic Large Language Model application (Allam),42 as part of the Saudi Vision 2030. In addition, Saudi Aramco unveiled the Aramco Metabrain AI—a generative AI model using 7 trillion data points it collected over its 90-year history.43 Key Saudi public entities are also investing heavily in AI and semiconductors, as in the case of Al Moammar Information Systems, which is investing $5 million in Anthropic—the developer of the LLM Claude44—and the Kingdom’s sovereign wealth Public Investment Fund (PIF) pledging its investment drive in the semiconductor industry.45 The Kingdom went a step further to secure digital infrastructure by launching Huawei’s cloud data center in Riyadh46 in addition to hosting several data centers led by U.S. companies including Intel,47 Oracle, and Microsoft.48

In the UAE, Falcons.AI—an artificial intelligence solution advisory company under the Advanced Technology Research Council (ATRC)—was launched in 2021. Subsequently, the Emirate of Abu Dhabi announced a large-scale artificial intelligence model, Falcon 180B,” developed by the Technology Innovation Institute (TII) of ATRC.49 Together with the commercialization arm of ATRC, VentureOne, TII launched AI71—an AI company—which developed the LLMs Falcons.AI or Falcon 180B.

Both Saudi Arabia and UAE are still in the early stages of setting regulatory mechanisms. Although SDAIA has established a national data governance structure for data classification in 2020, there have not been any updates on the policy since.50 SDAIA also released recently a first-ever document on generative AI regulatory guidelines51 In October 2023, the Saudi Communication Spaces and Technology Commission released an updated version of cloud computing service to align service provision with global standards.52 As for the UAE, the Minister of State for Artificial Intelligence, Digital Economy and Remote Work Applications Office issued a whitepaper on responsible metaverse, releasing AI-related policies and guidelines in 2023.53 The Minister has also promulgated its National AI Strategy,54 but has yet to begin a full-fledged policy drive on AI regulations.

China’s Role in AI and AI chips Development in the Gulf amid U.S. Curbs

In the current AI boom, Nvidia’s GPUs for parallel processing and SK Hynix’s HBMs are in high demand for generative AI implementations.55 Yet, in due course, different kinds of AI chips are expected on the horizon. NPU developments are underway. They are led by start-ups such as Rain Neuromorphics (Rain.AI)56—backed by the reinstated OpenAI CEO Sam Altman,57 who toured around the Gulf and East Asia claiming to raise $7 trillion58—or the $100 billion Project Izanagi spearheaded by Softbank CEO Masayoshi Son—funder of Saudi Arabia Vision Fund, and holder of 90% share in semiconductor architecture firm Arm.59 Simultaneously, big tech companies such as Microsoft, Amazon,60 Meta,61 and Google62 are designing AI chips in-house since semiconductors specifically intended for generative AI are required.

Saudi Arabia eyed these developments in AI chips and sought to invest in Rain.AI, but it was alleged that the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) has pushed Saudi Aramco’s venture capital, Prosperity7, to divest from Rain.AI, revealing the geopolitical risks for Saudi Arabia—the U.S. identified Prosperity7 as a backdoor for China’s acquiring GPUs based on the Saudi-Chinese AI collaboration.63 Nevertheless, under Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s lead, an initiative on AI called “Alat”64 was launched for semiconductors.65

China is striving to progress in AI, focusing investments inwards amid the BIS export controls of October 7, 2023. Yet Beijing looks to the Gulf for external collaboration and market access. In the ongoing tech cooperation between China and the two Gulf states, the presence of a vast workforce of Chinese software engineers is instrumental to the Gulf states’ development of AI. Indeed, China’s AI engineer workforce heavily supports Saudi Arabia’s initiative in AI development.66 This goes hand-in-hand with investments into Chinese tech companies Alibaba and SenseTime, which have secured deals with the Kingdom.67

In March 2024, UAE’s sovereign wealth fund Mubadala—owner of 89.4% of GlobalFoundries as of October 2021, formerly a child company of Advanced Micro Devices (AMD)68—has joined hands with UAE’s government-backed AI start-up, G42, to form a technology investment company, MGX, which aims to mobilize $100 billion in AI and semiconductor deals.69 In the meantime, the AI company led by Tahnoun bin Zayed Al Nahyan and run by CEO Peng Xiao, has divested its shares from TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance, under U.S. pressures given the deep ties with China. This signals challenges in terms of Emirati domestic capitalization and the indigenous push toward AI chips.70 In a recent development, G42 joined hands with Microsoft, with Microsoft announcing a $1.5 billion investment in G42,71 and the two companies investing in a $1 billion investment in a data center in Kenya72 upon the Kenyan President’s state visit to the U.S.73 Concerns remain on Capitol Hill regarding a plausible tech spill and China’s plausible access to advanced chips via G42.74

Policy Recommendations: for Gulf States as End-Users of Chips

As generative AI and its applications are poised to transform the global economy and military capabilities into the next decade, the Gulf’s investment in greater next-generation semiconductor manufacturing capacities comes with geopolitical risk. While digital technologies are a prominent part of the economic diversification agenda across the Gulf, these countries lack operational experience in the semiconductor industry. In addition, export controls add another layer of challenges. For instance, geopolitics and national security issues regarding Taiwan and the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) are not fully understood yet, while the Gulf grapples with its own intra-regional issues. There is also an understanding gap in chip supply chains, particularly in chip production nodes concentrated in East Asia (Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, and China) and Europe (Netherlands, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom), and in U.S.-dominated chip designs.

It is expected that the expansion of the U.S. chip export controls would impact the AI ambitions of Gulf states. Given that Gulf states are at the consumption node of the chip supply chain, they must consider the following, if they seek full-fledged transformation into the digital world utilizing chips: first, it is important to be aware of the chip industry operations and identify where they fit within the supply chain; second, they should identify their positions in the geopolitical landscape between the U.S. and China; and third, they should think through how they would build an industrial base and accumulate profound knowledge on chip supply chains grounded in the industry’s history. These efforts are necessary as the Gulf states are likely to be semiconductor end-users and not producers.

In the long run, such efforts would lead to the required roadmap for policy direction, not just for chip development but for AI as a whole. Being a player in the semiconductor industry necessitates decades of know-how, with continuous talent, technological knowledge, and capital upscaling. Nation states guard these elements heavily during the design and production phases given the crucial importance to their economies. The Gulf’s path toward indigenous chips production therefore is likely to be laden with difficulties. After all, geopolitical tensions are compelling the chip supply chain to be reshuffled through industrial policies across various global jurisdictions.

In addition, Gulf states would need to take national security concerns amid geopolitical risk seriously, to avoid being cut-off from the value chain and facing disruption in carrying out their digitization plans and AI development. Closer policy attention to the different countries’ policy responses to U.S. export controls in the chip supply chain and to the chip subsidy competition across jurisdictions could be beneficial for Gulf states to identify their potential place in the supply chain.

At the same time, jurisdiction-based legalization efforts for sovereign AI would be crucial for Gulf states. Updating data regulations and writing AI-related guidelines in risk prevention that may arise from LLMs—as in the case of “Frontier AI” that may bring catastrophic risks to humanity75—would be required for solid implementation and AI adoption—i.e., autonomous driving, flying taxis, and deployment in oil and gas production. Having concrete AI and data legislations that clearly define policy directions would allow for Gulf states to set realistic goals, fit for economic diversification.