The Saudi–Iranian Détente:

A Strategic Imperative

Issue Brief, February 2026

Key Takeaways:

Saudi-Iranian Rapprochement is Fragile, but Hangs On: Diplomatic engagement between Iran and Saudi Arabia has persisted despite the shock of the Israeli-American attack on Iran in June 2025 and the triggering of snapback sanctions. Riyadh and Tehran share an interest in reducing tensions, yet remain wary of shocks.

Trade Normalization Remains Mostly Aspirational: Bilateral agreements on technical cooperation promise to boost annual trade, driven by industrial development, increased investments, and tourism—but risks remain an obstacle to deepening ties.

Détente is a Strategic Priority for Tehran: Snapback sanctions have increased the economic uncertainty facing Iran, and the threat of future military attacks by Israel is ever-present. This is pushing the Iranian leadership to mend fences with its neighbors to mitigate risks.

The GCC’s Reaction to the 12-Day War Reinforced the Détente: The Gulf states’ condemnation of Israeli military actions against Iran, and clear signals that they should not be used as platforms for such attacks, have strengthened the reconciliation drive.

Introduction

Iran and Saudi Arabia are pursuing a détente. After a near decade-long break in diplomatic ties, both states appear keen to put animosities behind them. In January 2016, Saudi Arabia severed diplomatic ties with Iran after protesters stormed and set fire to the Saudi embassy in Tehran and consulate in Mashhad, in response to Riyadh’s execution of Shia cleric Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr.1 This diplomatic rupture fueled a bitter regional rivalry in Yemen, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, as Iran sought to project deterrence through allied states and non-state actors, while Saudi Arabia sought to contain what it saw as Iranian expansionism. However, Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman’s turn to diversifying the Saudi economy, in line with the ambitious Saudi Vision 2030, has pushed Riyadh to view tension with Iran as a drain on resources—an assessment shared by Tehran. The two countries resumed diplomatic relations in 2023, through Chinese mediation.

Iran’s pressing security and economic concerns have made improving relations with its neighbors an urgent priority. The regional and international landscape has significantly changed to the Islamic Republic’s detriment. Iran long pursued a model of asymmetrical warfare against Israeli and American interests, relying on a collection of state and non-state allies, under the banner of an Axis of Resistance. This model suffered a major setback from late 2023 onwards as Israel severely constrained Hamas and Hezbollah’s capabilities. Israel’s direct strikes on Iran in June 2025, followed by the United States’ bombing of Iranian nuclear facilities, further challenged Iran’s deterrence strategy.

Tehran also faces renewed economic pressure. The adoption of snapback sanctions by the United Nations Security Council in September 2025 heralded a new era of isolation. Against this backdrop, consolidating détente with Saudi Arabia has gained strategic importance for Iran’s leadership. This issue brief examines how a shared interest in repairing bilateral relations could be tested by broader geostrategic dynamics, and by how Tehran and Riyadh’s respective political leaderships navigate these tensions to prevent a return to escalation

Saudi Arabia’s refusal to allow its territory or airspace to be used in the June 2025 Israel–U.S. attacks on Iran vindicated the push for détente. Riyadh publicly condemned Israeli “aggressions against the brotherly Islamic Republic of Iran,”2 a remarkable statement given past animosities between Riyadh and Tehran. Iranian authorities acknowledged this, with Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi thanking the Kingdom “for its stance in condemning…Israeli aggression” and praising Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s efforts “to promote security and stability in the region.”3

The wave of protests that broke out in Iran in late December 2025 made the Saudi-Iran détente even more important to Tehran. As massive public anti-government demonstrations potentially jeopardize the foundations of the Islamic Republic, and U.S. President Trump threatens to resume strikes on Iran, Tehran continues to rely on improving relations with Saudi Arabia to mitigate tensions. Expressions of concern from Riyadh, describing another U.S. attack on Iran as a threat to regional security, arguably validate Tehran’s expectations.

Détente between these regional powers has opened the way for improved trade relations and better coordination of the Hajj pilgrimage for Iranian pilgrims. But the institution of snapback sanctions and U.S.-imposed secondary sanctions impede financial transfers and present serious hurdles. Furthermore, Iran and Saudi Arabia have not changed their strategic outlooks and divergent objectives in relation to the United States and Israel, differences which risk undermining this rapprochement. Saudi Arabia views the United States as a strategic security partner, and has indicated its willingness to establish formal relations with Israel once Palestinian statehood is achieved. From Tehran’s point of view, both the Israeli and U.S. presence in the Gulf are sources of instability in the region. This stark divergence of views is a major strain on Saudi-Iran relations.

Détente Under Stress

High-level contact between Saudi Arabia and Iran resumed after the 2023 agreement, including bilateral meetings between foreign ministers and security officials. President Pezeshkian has clearly broken with the message of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic, who repeatedly expressed disdain towards the Al Saud family.4 Iran’s leadership, including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, have considerably shifted away from that perspective. It is important to note that Pezeshkian invokes Islamic solidarity to describe relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia. To emphasize shared interests, Pezeshkian weaves ideological, religious, and strategic concerns into his narrative. Arguing that “Islamic countries, including Saudi Arabia, are our brothers,” he asserts that unity among Muslim states is the best protection against external threats.5 This framing has helped insulate the government from domestic accusations of weakness, by casting its engagement with Saudi Arabia as a form of defense against Western and Israeli pressure, rather than a concession.

The Saudi-Iran détente has so far proven resilient to shocks, notably the Israeli-American military strikes on Iran in June 2025. Israel’s attack on Iran, including those on nuclear and military facilities and strategic infrastructure such as the South Pars gas field, along with U.S. support through the bombing of three nuclear sites, was precisely the kind of escalatory event that would have previously pushed Riyadh and Tehran into opposing camps.6 Yet this time, both sides appeared keen to protect their recently resumed relationship.

Saudi Arabia condemned the Israeli attacks as a violation of Iranian sovereignty and urged all parties to avoid a wider conflict.7 The Kingdom also joined other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states in warning of the risks to regional security and energy flows.8 Iran, for its part, calibrated its retaliation to avoid implicating Saudi territory or assets. Araghchi stressed that Iran did “not seek to expand the conflict” into neighboring states, and framed Iranian responses as self-defense, even while the Iranian strike on the U.S. Al Udeid airbase in Qatar raised concerns in GCC capitals.

During a telephone call with Pezeshkian after the June 2025 strikes, Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman reiterated the Islamic solidarity narrative, asserting that “Saudi Arabia stands with its brothers in Iran and will spare no effort to support them.” 9 He added that “the entire Islamic world is united in backing Iran.”10 This message, unthinkable just a few years ago, signals that both Tehran and Riyadh’s leadership recognize a shared interest in preventing escalation and a wider regional war.

Despite these signals, the relationship remains fragile. It is built on elite calculations, and is heavily influenced by threat perceptions and years of mistrust. In both states, segments of the political and security establishment remain skeptical of the other. In Iran, hardline critics view Saudi Arabia’s close security ties with the United States and openness to normalizing relations with Israel, albeit conditional, as evidence of its unreliability and the fact that it remains part of the regional challenges facing Iran.11 In Saudi Arabia, memories of past Iranian support for attacks on Gulf oil infrastructure and shipping, along with concerns about Iranian nuclear and missile capabilities, continue to animate the security debate.12

Iran’s asymmetric deterrence strategy has been eroded by heavy losses among its allies and partners since October 7, 2023. Syrian president Bashar al-Assad’s regime fell to an anti-Iranian force, Hezbollah is under sustained Israeli military pressure in Lebanon, and Hamas is severely degraded in Gaza. This presents the risk that future escalations could see Iran use overt tools of power projection which would in turn provoke sharper responses from the United States and its regional partners.

The snapback of UN sanctions against Iran, under the framework of the JCPOA, has highlighted the securitized nature of Iran’s nuclear file. The reimposition of arms embargoes, missile restrictions, and financial isolation could potentially serve as a cover for more covert or overt action against Iranian facilities by Israel and the United States. The ongoing deadlock over Iran’s nuclear program, as well as heightened tensions between Tehran and Washington in the wake of a new wave of protests in Iran, is likely to test Saudi Arabia’s ability to maintain a balanced posture in the face of Washington’s hard line on Iran.

Trade Normalization Remains Aspirational

Economic ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia remain under-developed. Both are large hydrocarbon producers with ambitious economic diversification agendas. In March 2025, official Iranian statistics suggested that non-oil trade between the two countries stood at around $25 million that fiscal year, with roughly 61,000 tonnes of goods exchanged.13 Iranian exports to Saudi Arabia include steel products, pistachios, raisins, carpets, glass sheets and apples, reflecting some diversification.14

Iranian officials hold ambitious ideas for the future of Saudi-Iran trade ties with expectations of a joint chamber of commerce to accelerate bilateral trade, particularly in non-oil consumer goods.15 This is consistent with President Pezeshkian’s desire to normalize ties with neighboring countries. For Saudi Arabia, expansion of trade with Iran fits into a wider effort to position the Kingdom as a regional investment and logistics hub, and is aligned with its National Vision 2030.

Nevertheless, structural obstacles are substantial. Snapback sanctions and U.S. secondary sanctions deter major Saudi and international firms from entering the Iranian market. The reimposition of UN sanctions in September 2025 restored restrictions on Iranian banking and shipping that had previously been relaxed under the 2015 nuclear deal. Financial institutions across the GCC are exposed to Western regulatory regimes and would face significant penalties if they evaded the sanctions.

Both economies are undergoing internal transformations. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 agenda prioritizes large-scale investments in infrastructure, tourism and technology, with an emphasis on attracting foreign capital. Iran, by contrast, has increasingly turned to Russia and China to offset Western sanctions. While this does not preclude bilateral ties, it means that the Saudi and Iranian development trajectories are currently oriented towards different external partners and regulatory ecosystems. This complicates efforts to establish joint ventures or integrated supply chains.

Moreover, the legacy of mistrust is not easy to overcome. In 2019, Saudi Arabia’s largest oil processing plant, in Abqaiq, was hit by an Iranian-made drone fired by the Houthis in Yemen.16 This was a shocking episode for the Saudi leadership, demonstrating Iran’s destructive reach in the wider region. At the same time, Iranian enterprises are concerned about the potential for sudden policy shifts in Riyadh that might follow changes in Saudi’s perceptions of regional risk, or in the Kingdom’s relations with Washington. Both sides recognize that any major political shock, such as a renewed crisis over Iran’s nuclear program, a flare-up in Yemen, or another cycle of hostilities between Israel and Iran, could disrupt long-term commercial ties.

Despite these constraints, incremental progress is visible. The resumption of direct flights between Mashhad and Dammam in December 2024, after a nine-year hiatus, has created new channels for religious tourism and business travel, including facilitating Saudi Shia citizens’ visits to the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad.17 Iran’s broader non-oil export profile has also strengthened. According to official sources, Iran’s total non-oil exports in 2025 reached $74 billion, which includes a jump in non-oil exports to Saudi Arabia ($12.5 billion) putting it on par with Iraq.18 Saudi non-oil exports, meanwhile, are oriented towards markets such as the United Arab Emirates, India, and China.19

The economic dimension of the Saudi-Iran détente consists of small-scale, symbolic measures. It provides a useful narrative of mutual gain, and helps embed the idea of normalization of ties in bureaucratic interactions, notably airline coordination and commercial delegations. But without a significant easing of sanctions and a higher degree of political trust, comprehensive trade ties remain aspirational.

Hajj Diplomacy

Arrangements for the Hajj pilgrimage have long been a sensitive barometer of relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia. In the past, Iran challenged Saudi Arabia for failing to represent Muslim interests globally, and criticized its custodianship of Mecca. In 1987, Iranian authorities organized pilgrim rallies in Mecca against the United States, Israel and the Saudi ruling family, resulting in the deaths of some 400 pilgrims.20 In 2015, at least 1,000 pilgrims died in a crowd crush during the Hajj pilgrimage in Mina, including approximately 464 Iranian pilgrims, an event that significantly worsened Iran–Saudi relations.21

In recent years, the tide has turned. Following the 2023 restoration of diplomatic ties, Saudi and Iranian officials negotiated practical arrangements for Iranian pilgrims, including quotas, consular services and transportation. By 2025, the authorities agreed on an increased quota for Iranian pilgrims and improved management for the 2026 Hajj, including the facilitation of direct flights for pilgrims from several Iranian cities.22 Hajj coordination has generated technocratic interaction between Riyadh and Tehran. Iranian and Saudi officials coordinate visa procedures, health protocols, accommodation, and transport.

Hajj diplomacy has emerged as an avenue for technical cooperation in the Saudi-Iran rapprochement. It is grounded in recurring, predictable processes, and it mobilizes religious narratives that emphasize unity over division. Technical cooperation for Hajj is also scalable. Joint crisis-management and consular coordination developed around the Hajj can inform wider collaboration on crisis management, public health, and people-to-people exchanges. But Hajj diplomacy and its potential as a model for bilateral cooperation are still subject to the volatility of the broader geopolitical landscape.

Détente Under the Shadow of Trump

The reimposition of UN sanctions and President Trump’s campaign against Iran have aggravated tensions. Washington’s renewed pressure on Iran is multipronged: in addition to economic pressure, Iran has been subjected to direct military attacks on its nuclear and military facilities, aimed at degrading its strategic capabilities. Repeated Israeli and American threats of attacks on Iran continue to shape Tehran’s strategic calculations.

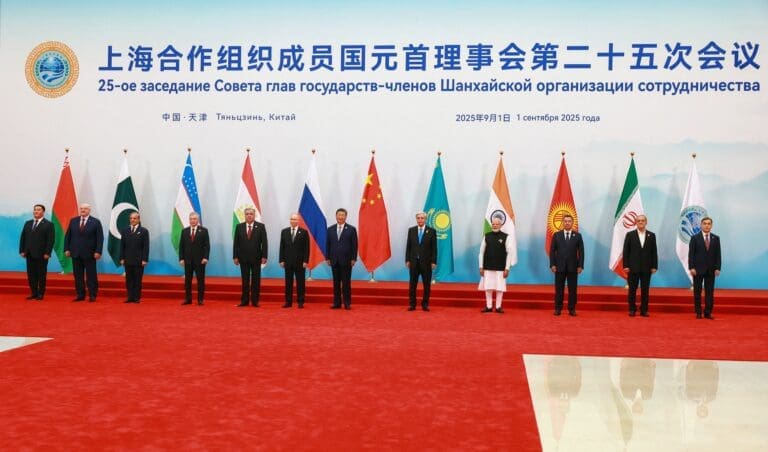

In this context, the Iranian leadership views regional de-escalation as a strategic necessity. The Saudi–Iran détente therefore serves important functions. It helps Iran demonstrate that it is not isolated in its immediate region. The public condemnation of the June 2025 Israeli-American attacks on Iran by Saudi Arabia and other GCC states, and criticism of U.S. attacks on Iranian nuclear sites, were noteworthy, allowing Tehran to demonstrate that even U.S. partners in the Gulf view Israeli and American actions as destabilizing.

Détente has also reduced the likelihood that Saudi territory or airspace will be used to facilitate future military operations against Iran. The Iranian leadership views engagement with Riyadh as part of a broader strategy to pacify the GCC arena. The Iranian authorities appear cognizant that their sporadic threats to disrupt shipping in the Strait of Hormuz is a stress point for GCC states.23 Under Pezeshkian, the Iranian authorities have been cautious to avoid such threats and signal that they do not seek to escalate tensions in the Gulf. 24

U.S. expectations of Saudi alignment with snapback measures and the enforcement of UN sanctions present a challenge for Riyadh. Such compliance would open Saudi Arabia to accusations that it is facilitating economic warfare against Iran, reversing the tentative gains made in repairing bilateral relations. So far, the Saudi leadership has refrained from taking overt actions to enforce snapback sanctions.

Conclusion

The Saudi–Iranian détente is a response to an increasingly volatile regional environment. It has so far proven resilient, yet remains fragile and susceptible to miscalculation, domestic discontent, and U.S. pressure. There is clear interest among regional stakeholders in supporting a Saudi–Iran security dialogue to develop a mechanism for crisis management in the Gulf and the wider region. Regular institutionalized channels between national security councils, foreign ministries, and defense establishments can help both sides clarify red lines and avoid misunderstandings. This will be important for coordinating responses to naval, aerial, and cyber threats. These dialogues do not presuppose strategic alignment. Rather, they are intended to institutionalize détente, managing the rivalry in ways that prevent inadvertent escalation. Insulating Hajj diplomacy and other forms of religious cooperation from wider political disagreements also provides an opportunity for trust and confidence-building. Depoliticized Hajj management could offer a model for engagement in other fields.

Saudi-Iran economic links remain under-developed, but hold potential for considerable growth, by focusing on low-risk sectors that are less exposed to UN sanctions and financial compliance challenges—such as health, environmental management, disaster relief and academic cooperation, as well as religious tourism (although this could remain sensitive). By demonstrating that limited economic cooperation can deliver mutual benefits without triggering sanctions exposure, such projects have the potential to build constituencies with a stake in sustained engagement.

Thus far, the steps Saudi Arabia and Iran have taken to repair their relationship do not elevate their relationship into a partnership; but they could help consolidate a pattern of managed rivalry, anchored in regular and functional cooperation based on their shared interest in preventing regional war. In the context of renewed international pressure on Iran (sanctions, weakened deterrence and threats of future Israeli attacks), détente between Iran and Saudi Arabia represents a significant achievement for Iran. The Saudi position vis-à-vis the June 2025 U.S.-Israel-Iran war and the activation of the snapback sanctions mechanism hold important implications for the Saudi-Iranian détente.

These experiences have strengthened Iran’s appetite for improved relations with Saudi Arabia, which is perceived to be able to generate concrete diplomatic dividends. It has also reinforced Saudi perceptions that keeping open diplomatic channels with Tehran is essential. These dynamics create a solid foundation for sustaining momentum to improve bilateral relations.

Endnotes

1 “Saudi Arabia cuts ties with Iran as row over cleric’s death escalates,” Reuters, January 4, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/saudi-arabia-cuts-ties-with-iran-as-row-over-clerics-death-escalates-idUSKBN0UH01E/.

2 “Saudi Arabia Strongly Condemns the Blatant Israeli Aggressions Against Iran,” Saudi Press Agency, June 13, 2025, https://www.spa.gov.sa/en/w2339269.

3 “Saudi crown prince, Iran’s FM hold ‘fruitful’ talks on bilateral ties, regional security,” Press TV, July 9, 2025, https://www.presstv.ir/Detail/2025/07/09/750874/Iran-Abbas-Araghchi-Jeddah-security-stability.

4 Ervand Abrahamian, Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic (California: University of California Press, 1993), p.30.

5 “Iran’s President Urges Unity among Muslim ‘Brothers’,” Tasnim News Agency, October 3, 2024, https://www.tasnimnews.com/en/news/2024/10/03/3170997/iran-s-president-urges-unity-among-muslim-brothers.

6 “Iran does not want conflict with Israel to expand but will defend itself, foreign minister says,” Reuters, June 15, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iran-does-not-want-conflict-with-israel-expand-will-defend-itself-foreign-2025-06-15/.

7 “Saudi Arabia condemns Israeli strikes on Iran, urges immediate halt to escalation,” Saudi Gazette, June 13, 2025, https://www.saudigazette.com.sa/article/652660.

8 “Gulf Countries Condemn Israel’s Attack on Iran,” Asharq Al-Awsat, June 13, 2025, https://aawsat.news/n76hb.

9 “MBS says Islamic world backs Iran in call with Pezeshkian,” Al Mayadeen, June 15 , 2025, https://en.mdn.tv/8Vub.

10 Ibid.

11 “Saudi Arabia wants America to restrain Iran without being provoked/ Why does Bin Salman want Iran and America to negotiate?,” Tabnak, November 20, 2025 (in Farsi), https://www.tabnak.ir/005cuz.

12 Ali Alfoneh, “Iran Looms Over Saudi Visit to Washington,” Arab Gulf States Institute, November 18, 2025, https://agsi.org/analysis/iran-looms-over-saudi-visit-to-washington/.

13 “Iran-Saudi Arabia annual non-oil trade stands at $25m,” Tehran Times, April 15, 2025, https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/511847/Iran-Saudi-Arabia-annual-non-oil-trade-stands-at-25m.

14 “Iran’s non-oil exports to Saudi Arabia increase 99-fold,” TV BRICS, March 14, 2025, https://tvbrics.com/en/news/iran-s-non-oil-exports-to-saudi-arabia-increase-99-fold-/.

15 “Iran and Saudi Arabia are ready to establish a joint chamber of commerce,” The Hamedanian Trading Company, January 31, 2025 (in Farsi), https://hamedaniantc.com/news/%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86-%D9%88-%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A8%D8%B3%D8%AA%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%8C-%D8%A2%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%87-%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%AC%D8%A7%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D8%AA%D8%A7%D9%82-%D9%85%D8%B4%D8%AA%D8%B1/.

16 “Saudi Arabia oil facilities ablaze after drone strikes,” BBC News, September 15, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-49699429.

17 “Flights resume between Iran’s Mashhad and Saudi’s Dammam as tensions ease’,” Reuters, December 23, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/flights-resume-between-irans-mashhad-saudis-dammam-tensions-ease-2024-12-03/.

18 “New figures: Iran-Saudi trade sees astonishing 6,483% growth,” Iran Front Page, April 11, 2025, https://ifpnews.com/new-figures-iran-saudi-trade-sees-astonishing-6483-growth/.

19 “Saudi Arabia’s non-oil exports rise 5.5% in August: GASTAT,” Arab News, October 26, 2025, https://www.arabnews.com/node/2620286/business-economy.

20 John Kifner, “400 die as Iranian Marchers Battle Saudi Police in Mecca,” The New York Times, August 2, 1987, https://www.nytimes.com/1987/08/02/world/400-die-iranian-marchers-battle-saudi-police-mecca-embassies-smashed-teheran.html.

21 “First Hajj stampede bodies arrive in Iran,” Al Jazeera, October 3, 2015, https://aje.io/s9pjg.

22 “Saudi Arabia Agrees to Increase Iran’s Hajj Quota,” International Quran News Agency, May 30, 2025, https://iqna.ir/en/news/3493276/saudi-arabia-agrees-to-increase-iran%E2%80%99s-hajj-quota-%C2%A0.

23 Mousavi Fard Seyed Mohammad Reza, et al, “The effects of military seizures in the Strait of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandeb on world peace and security with emphasis on energy warfare,” Geography and Human Relationships, April 3, 2025, https://www.gahr.ir/article_218133_en.html.

24 “Araghchi: Closing Strait of Hormuz not Iran’s official policy,” IRNA, August 27, 2025, https://en.irna.ir/news/85923582/.