The GCC’s Evolving Trade Networks:

Navigating Fragmentation and Diversification

Policy Paper, January 2026

Abstract

The Gulf states’ trade relations are in transition. While making progress on diversifying their economies, they continue to seek a balance between hydrocarbon exports and post-oil industries, as well as between Western and Eastern trading partners. Meanwhile, they remain exposed to oil price volatility, the retreat of globalization, and frequent global and regional supply-chain disruptions. Geopolitical and financial relations keep the Gulf oriented to the West despite the latter’s waning economic importance. On the other hand, Gulf trade with Asia is booming, although the balance could tip to the Gulf’s disadvantage if current trends prevail. The Gulf still has few high-value-added exports, whether from manufacturing or services.

This paper examines Gulf trade data and current trade policies, developing four policy recommendations for the region’s governments as they navigate this shifting trade landscape.

Key Recommendations

Accelerate the Transition away from Hydrocarbon Exports: The countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) should reassess and upgrade their diversification strategies, adopting more structured, state-led industrial policies inspired by East Asian models, augmenting traditional heavy industries with sectors like defense and pharmaceuticals. They should also support export-oriented small and medium enterprises (SMEs), through improved state capacity and specialized agencies.

Strengthen Regional Trade Relations: To address languishing intra-GCC trade, members of the bloc should coordinate industrial strategies, expand shared logistics infrastructure, and harmonize standards to ease trade. This would enhance economic resilience and help diversify their partnerships.

Increase Self-Sufficiency: Recent geopolitical shocks and increasing dependence on Chinese imports have underscored the Gulf’s need for greater self-sufficiency and supply chain resilience. Policy responses should blend export promotion with targeted import substitution, facilitate technology transfers through joint ventures, and diversify supply chains.

Reduce the Trade Deficit in Services: Despite efforts to build a post-oil knowledge economy, the GCC runs persistent trade deficits in services, especially IT and business services. Addressing this requires developing local talent and business, fostering technology transfer and joint ventures through incentives and regulatory reform.

Introduction

Global trade is facing unprecedented upheaval, from the Trump administration’s chaotic trade wars to the threat—or reality—of conflict disrupting commerce through chokepoints such as the Straits of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandeb. Coming in the wake of pandemic-era supply chain disruptions, these spikes of turbulence are accelerating “slowbalization,” a trend of stagnating world trade since the global financial crisis of 2008, which ended the globalization rally of the early 2000s.1 All this has been accompanied by the progressive decline of the World Trade Organization (WTO),2 a fracturing of trade relations,3 and increasingly coercive United States trade policies,4 from weaponizing the SWIFT international payments system to technology bans aimed at curbing China’s technological catch-up.5

For the states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), these shifts demand a strategic recalibration. They are caught up in two binaries: that of trade sectors, juxtaposing the still-dominant fossil-fuel industry with post-oil alternatives, and that of geography, contrasting the traditional orientation toward the West with the promise of a rising Asia. GCC governments are navigating these tensions through economic policy, trade negotiations, strategic bloc alignments (e.g. with BRICS), and regional integration. This paper analyzes the GCC’s evolving trade patterns and policies, then proposes actionable policies for resilience.

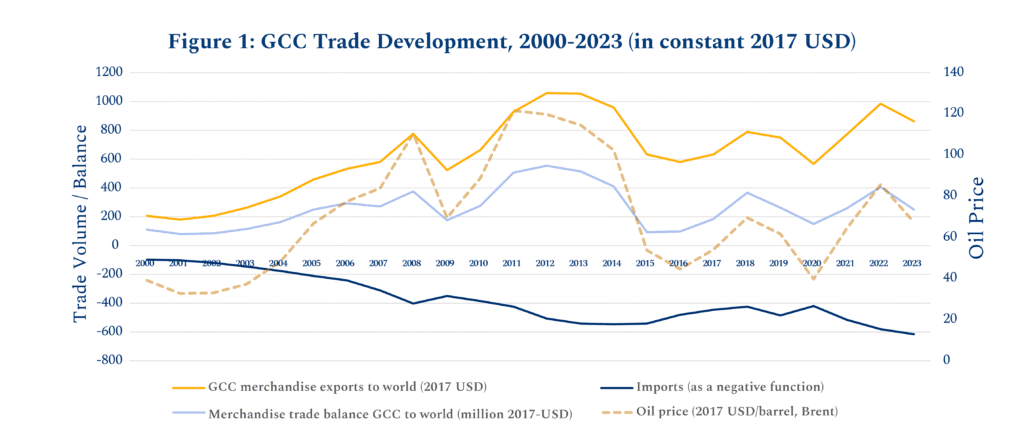

Quantifying the Evolution of GCC Trade

Figure 1 shows the evolution of GCC merchandise exports, in real terms, since 2000. The GCC’s main exports are hydrocarbons and commodities such as petrochemicals, which are closely correlated with oil prices. As a result, GCC export revenues follow global oil prices very closely, multiplying during the rally of the early 2000s and again after the 2008 crisis, before collapsing in the wake of the 2014 oil price crash. In the last decade, the region’s non-oil exports have increased, although export volatility and fiscal health remain closely related to oil prices, as demonstrated by the spike in 2022, when oil prices surged following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Sources: Energy Institute, 2025 Statistical Review of World Energy, 74th edition (London: Energy Institute, 2025); OECD Database, “Bilateral Trade in Goods by End-use: 2025 release,” accessed October 15, 2025; World Trade Organization (WTO) Stats, “Merchandise exports by product group – annual (Million US dollar); World; Product/Sector: Total merchandise; Years: 2000-2024,” accessed October 15, 2025; World Bank Statistical Database, “GDP deflator (base year varies by country) – United States,” accessed October 15, 2025.6

By comparison, Figure 1 also shows that the dollar value of Gulf imports, while following the same broad trends and reflecting the same shocks, is much less volatile, tracking world trade more closely.7 Notably however, for the past two years, imports have continued to grow, bucking downward trends in both oil prices and global trade. The implementation of major projects and strong growth in the expatriate population in several Gulf countries have driven import demand (particularly of consumer goods and capital goods, such as for the construction industry). As a consequence, the GCC’s trade balance has returned to 2006 levels in real terms. If current trends continue, this could considerably reduce the trade balance, especially if combined with weaker fossil fuel exports.

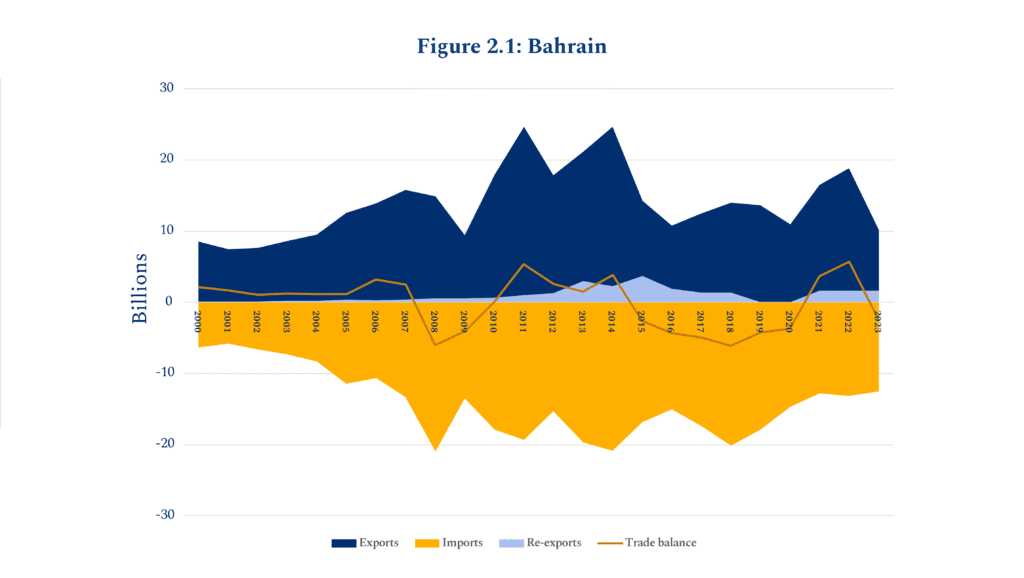

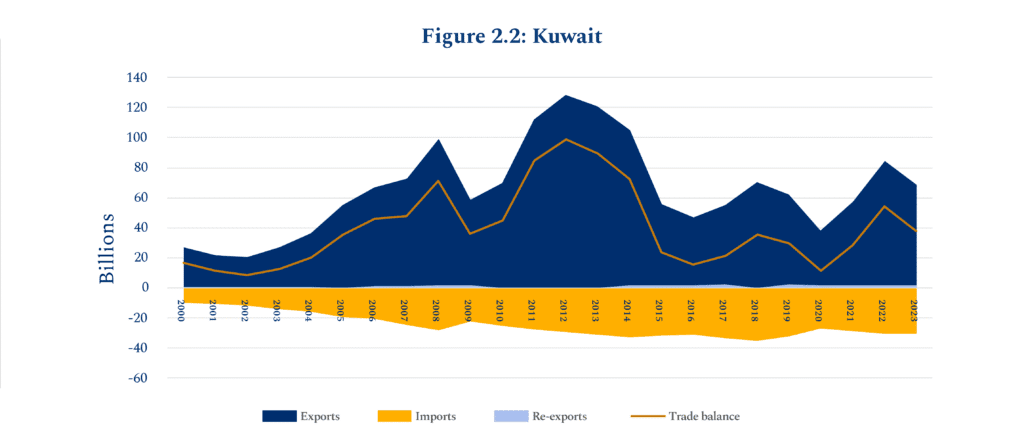

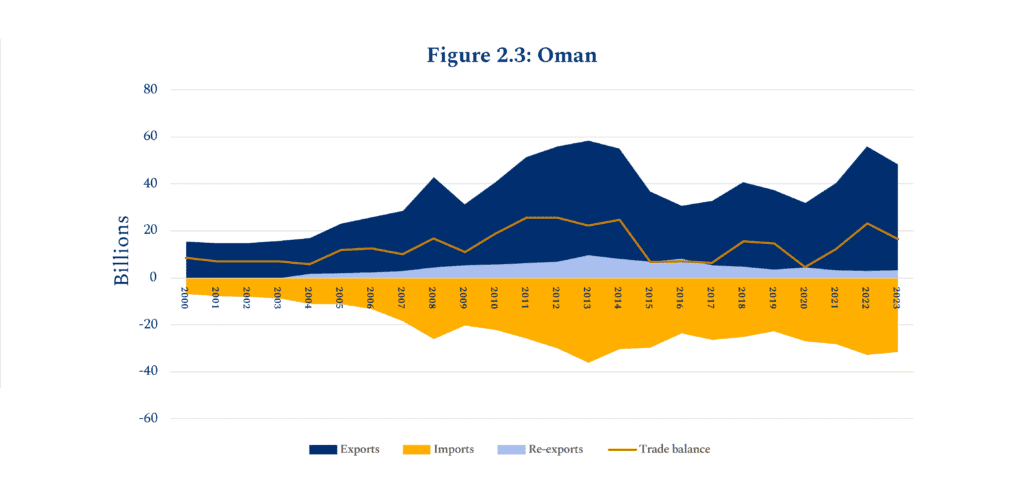

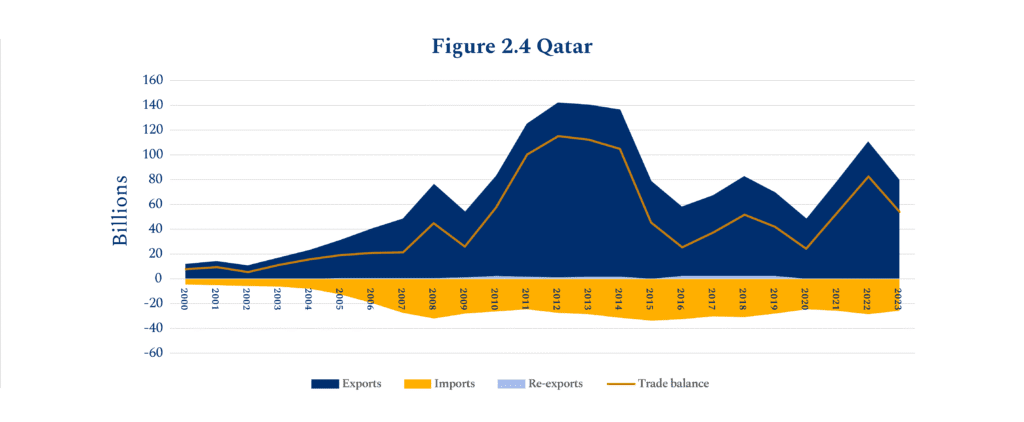

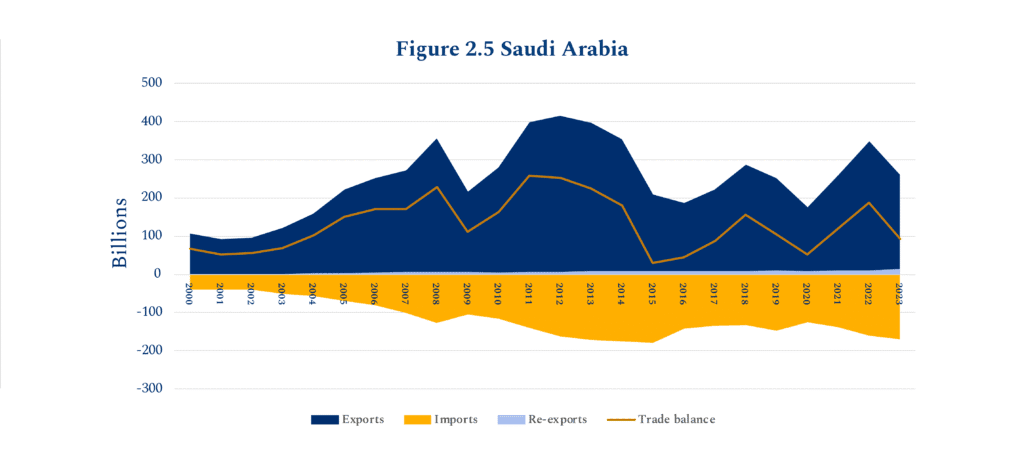

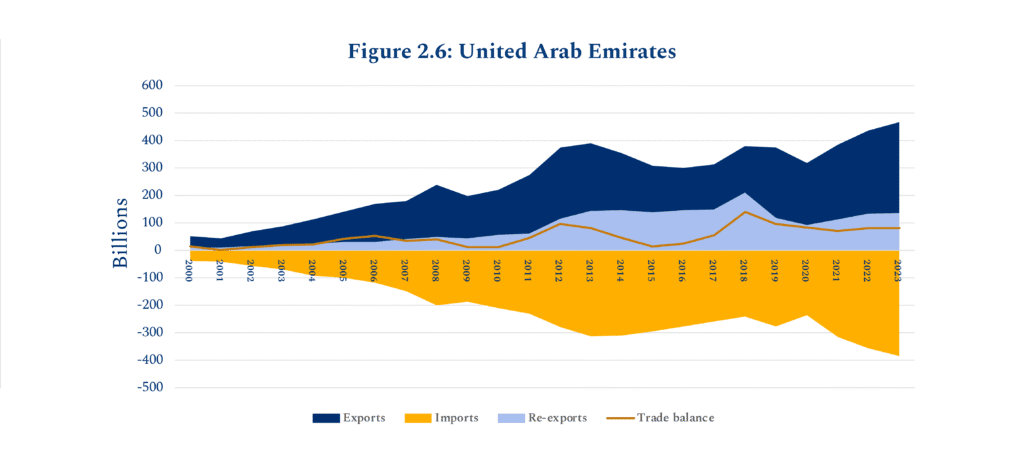

Figure 2 shows exports, imports, and trade balances for each GCC country. The country that has best avoided export volatility related to oil prices is the United Arab Emirates. Concurrently, it has seen rapid import growth, curtailing its trade balance. Notably, the UAE also has the highest share of re-exports, making up about 30% of exports in 2023. Generally, GCC countries have struggled to regain pre-2015 trade surpluses (in real terms); Bahrain has even experienced spells of trade deficit.

Figure 2: Exports, Imports, and Trade Balances by GCC Member State, 2000-2023 (in constant 2017 USD).

Source: OECD Database, “Bilateral Trade in Goods by End-use: 2025 release,” accessed October 15, 2025.

The GCC’s Trading Partners

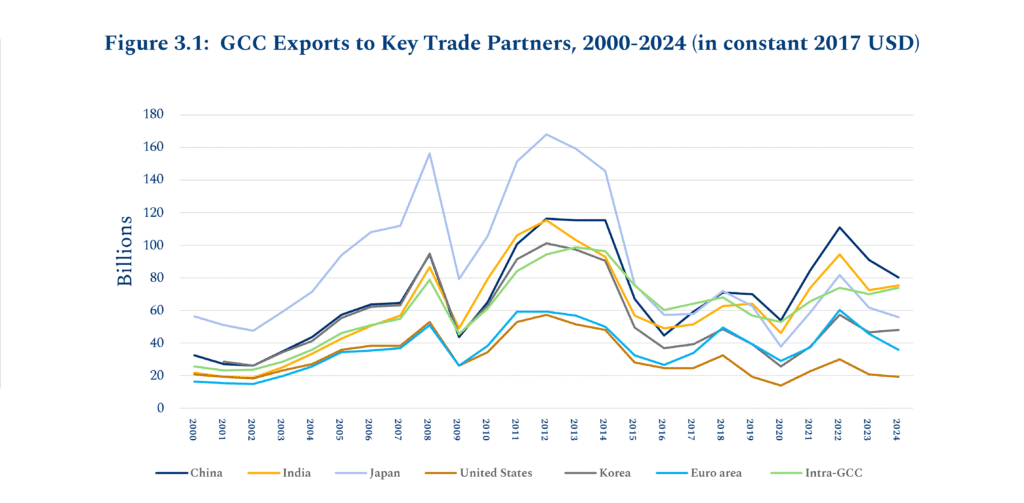

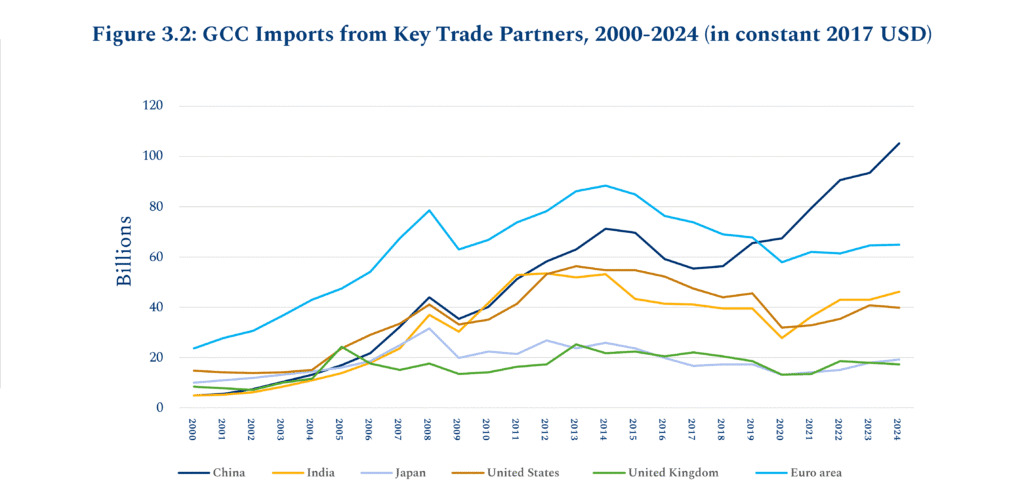

Plotting total exports and imports obscures diverging trends in both export destinations (Figure 3.1) and import sources (Figure 3.2). In both cases, the rise of China stands out. In 2019, it overtook Japan as the GCC’s leading export destination, then in 2020 outstripped the Euro area as the leading import source. Exports have dropped across all major markets since the peak related to the 2022 oil price spike. Imports from China are especially striking, with a sustained increase since 2018, almost doubling in real terms, and creating a rapidly growing bilateral trade deficit for the GCC.

Figure 3: GCC Exports and Imports with Key Trading Partners, 2000-2024 (in constant 2017 USD)

Source: IMF Data, “International Trade in Goods (by partner country) (IMTS),” accessed October 15, 2025.

India is now the Gulf’s second-most important export market, having quadrupled in real terms since the turn of the millennium, and is also an increasingly important source of imports, having overtaken the U.S. in 2021, but still leaving the GCC with a large trade surplus.

The West has declined in importance on both sides of the equation. The GCC has a persistent trade deficit with the Euro area, with exports having remained persistently low for 20 years. Europe used to be the Gulf’s most important source of imports, peaking in 2014 and stabilizing after 2020. Exports to the U.S. have long been low, and have declined since 2012, with the rebirth of large-scale domestic U.S. hydrocarbon production. Imports from the U.S. have followed the same trajectory as the Euro area, albeit to a lesser degree.

Intra-GCC trade has struggled to regain its pre-2008 level. After two slumps in the 2010s, intra-GCC exports have grown since 2020, indicating a re-regionalization of trade since the coronavirus pandemic and increasing opportunities for trade between GCC states as a result of post-oil diversification—although a significant part of intra-GCC trade is re-exports (see also Figures 2 and 4).

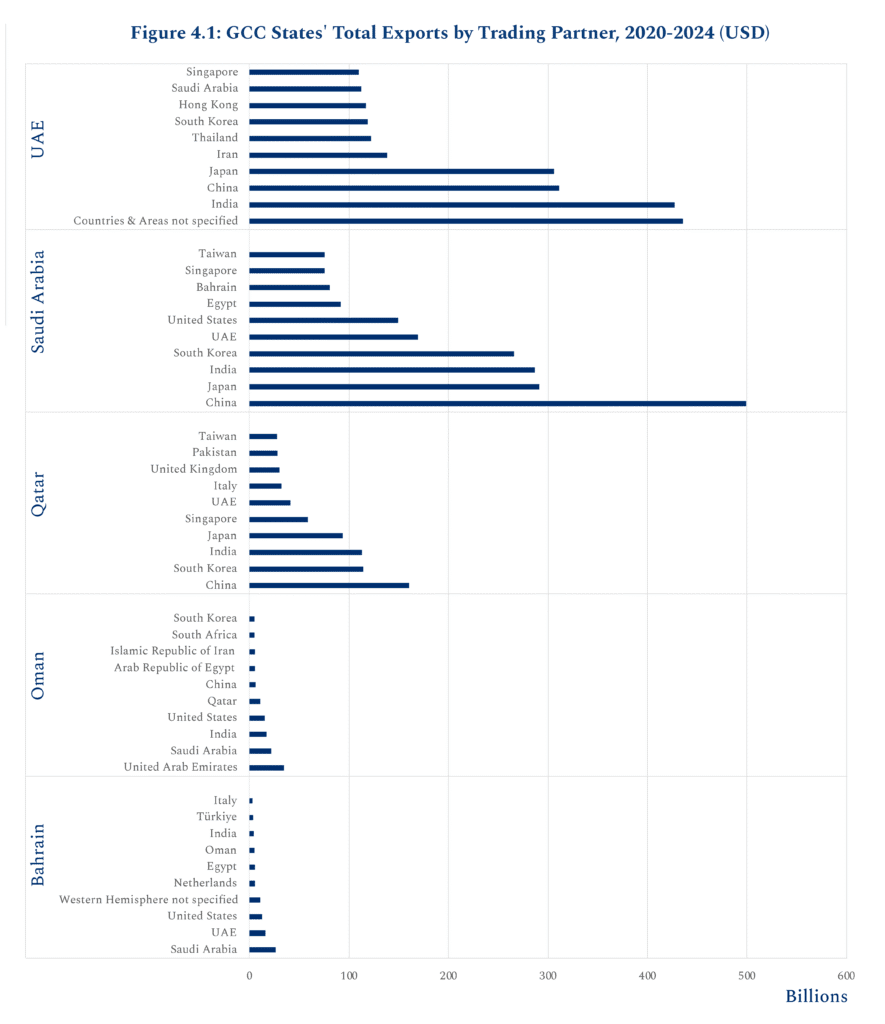

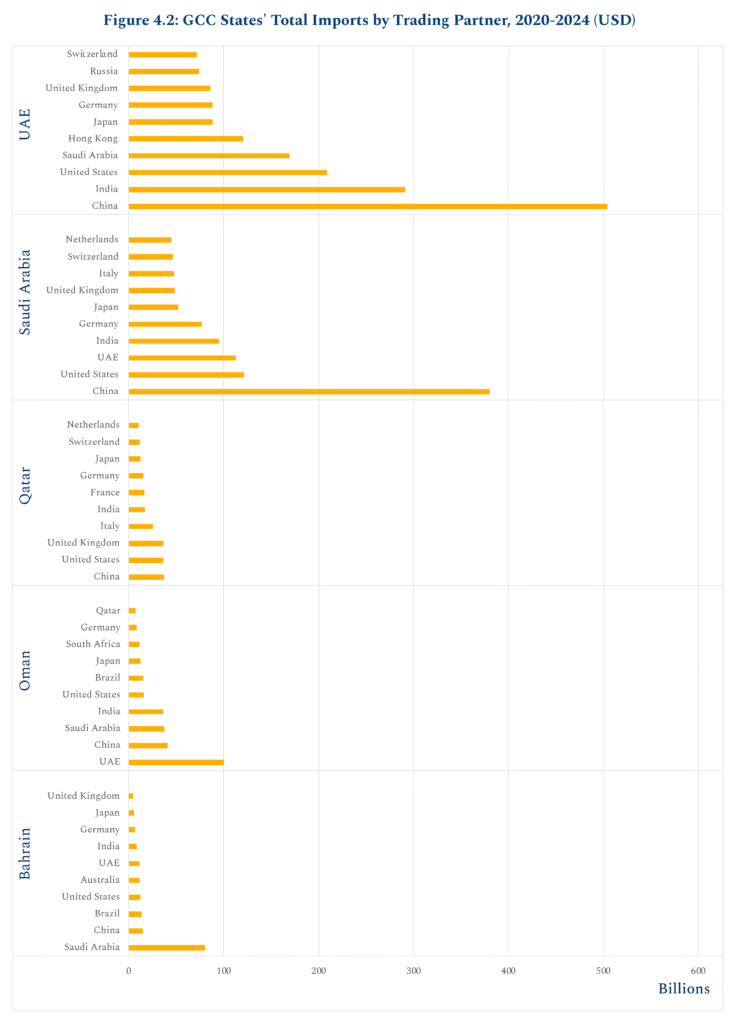

Figure 4: GCC States’ Trade by Counterpart, 2020-2024 Totals (USD)

Source: IMF Data, “International Trade in Goods (by partner country) (IMTS),” accessed October 15, 2025.

Figure 4 shows cumulative exports to (4.1) and imports from (4.2) each Gulf country’s most important trading partners from 2020 to 2024. While they share some similarities, such as a growing reliance on China for imports, they also have notable differences: China, India, Japan, and Korea are the top partners of Saudi Arabia and Qatar, while the UAE favors India, China, Japan, and Iran. The only Western country featuring as a major export destination is the U.S., ranking sixth for Saudi Arabia and third and fourth for Bahrain and Oman, respectively. Substantial trade is with undisclosed counterparts; for the UAE, “not specified” is the top category.8

While GCC exports are concentrated in a handful of counterparts, Bahrain and Oman stand out in that their trade is mostly routed through logistics hubs in neighboring Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Until 2017, Qatar also depended on re-exports from the UAE and Saudi Arabia, but that changed with the 2017-2021 blockade.

Imports are dominated by goods from China and, to a lesser degree, the U.S., which is a top-three source of imports into Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar. Saudi Arabia is an important exporter within the GCC, being the top source of imports for Bahrain (by far), as well as making third place for Oman and fourth place for the UAE.

The arms trade makes up a significant portion of imports, helping explain this distribution. Together, GCC countries make up 20% of global arms imports. From 2020-2024, Qatar and Saudi Arabia were the world’s third- and fourth-largest arms importers; Kuwait, the UAE and Bahrain ranked 10th, 11th, and 23rd, respectively. The U.S. has been the top supplier, accounting for between 42% (the UAE) and 97% (Bahrain). Saudi arms imports have declined 41% compared to 2015-2019, but Qatar’s have increased significantly. The UK, France, and Italy also featured among the top arms exporters to the GCC, including of fighter jets9 and navy vessels.10

Examining GCC Trade by Sector

Hydrocarbons

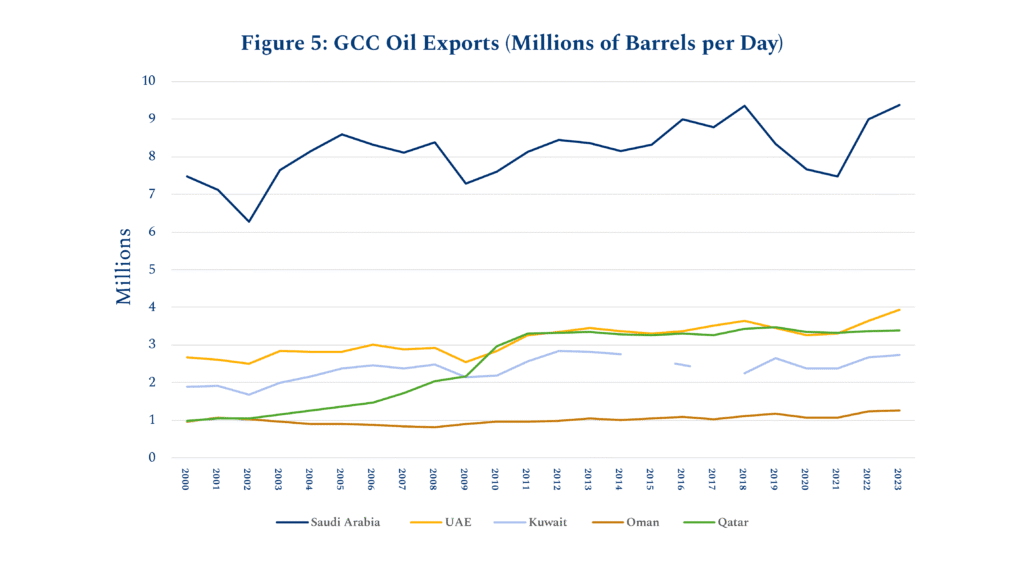

The tight correlation between GCC exports and oil prices shows that GCC exports remain dominated by hydrocarbons. Indeed, while energy prices are highly volatile, the volume exported from the Gulf is remarkably stable (Figure 5).11 Saudi Arabia, as the most proactive producer, has seen the most volatility in its oil exports, notably a four-year trend of declining exports which reversed in the wake of the Ukraine war. Simultaneously, the UAE, Kuwait and Oman have increased their exports to record levels, while Qatar’s oil exports remain constant (although Qatar relies more on natural gas).

Figure 5: GCC oil exports (million barrels per day)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED), “Total Oil Exports Including Crude for Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar,” accessed October 15, 2025.12

The general outlook for the Gulf hydrocarbon sector remains robust. The Ukraine war shifted additional demand to the GCC,13 and the two largest Gulf oil exporters plan to expand production, with Saudi Arabia leading a relaxation of OPEC+ quotas14 and the UAE investing $150 billion into infrastructure to raise production capacity to 5 million bpd by 2027.15 Not only is GCC oil production likely to remain near or above 2024 levels over the medium term, but non-associated gas production for LNG and domestic consumption is also set to rise substantially, particularly in Qatar.16 Furthermore, the trend of reducing crude exports in favor of refining and processing crude domestically is likely to continue, as the GCC countries continue to climb the value chain.17

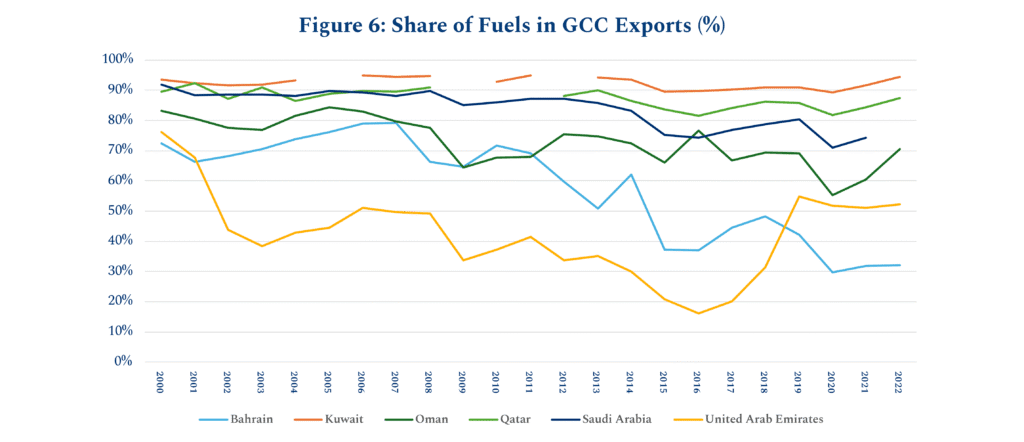

Figure 6: Share of Fuels in GCC Exports (%).

Source: World Bank: World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), “Trade Stats; Product Category: Fuels Share,” accessed October 15, 2025.

As a result, fuels still represent the majority of Gulf exports (Figure 6), particularly for Qatar and Kuwait. Fuels make up three-quarters of export revenues for Saudi Arabia and Oman, but only about one-third for Bahrain, which has limited reserves. The UAE’s fuel exports still make up slightly more than 50% of the total. While this is considerably lower than most other GCC member states, this level was already reached in the 2000s and fell to 17% in 2016, at the height of the oil price slump, before rebounding. As such, with the exception of Bahrain, none of the GCC countries will likely see a significant further decoupling of export revenue from fossil fuels in the near future.

Non-Oil Merchandise Trade

The Gulf enjoyed a comparative advantage in the trade of hydrocarbons both directly—such as the top categories for Saudi Arabia (petroleum oils) and Qatar (liquefied propane and butane)—and indirectly, through byproducts of oil production like sulfur and pyrites (the UAE’s most over-represented export), petrochemicals, or products that harness the region’s cheap energy (Bahrain’s aluminum and pig iron).18 Other natural resources (stone, sand, gravel) and traditional sectors predating the oil era (pearls, jewelry, gold) are also heavily represented. However, higher-value-added goods like electronics remain absent.

Gulf governments are acutely aware of the continued prominence of the hydrocarbon sector and have developed industrial policies to reduce import dependence on, and boost export capacity for, manufactured goods. This includes the defense industry, with national champions like SAMI (Saudi Arabia) and Barzan (Qatar), but also other sectors, from automotives to dairy and ceramics to industrial components.19

Services

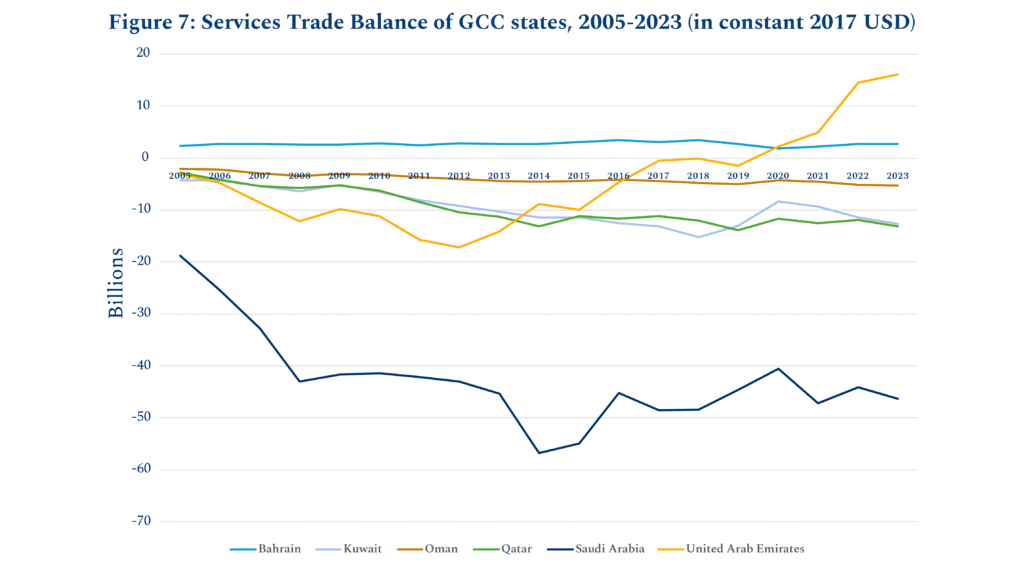

While discourse on trade focuses on merchandise, trade in services has become increasingly important.20 In contrast to physical goods, most GCC countries run a persistent trade deficit in services, in particular Saudi Arabia (see Figure 7). The two exceptions are Bahrain, which has had a sizable surplus for decades, and the UAE, which has been in surplus since 2019. A look at services sub-sectors reveals the drivers of these balances (see Table 1).

For the UAE, the largest surpluses come from travel and transport, due to the strong growth in tourism and MICE (meetings, incentives, conferences, exhibitions), as well as logistics and entrepôt activities, totaling a surplus of $38 billion in 2023. The UAE’s largest deficit is in IT and telecommunications services, amounting to about $15 billion.21

International visitor spending in the UAE rose to $59 billion in 202422 while logistics firm DP World (with revenue of $20 billion) has branched out from shipping to value-added services such as supply chain management, trans-shipment services, and multimodal transport involving sea, air, and land routes. UAE ports have a throughput of 21 million twenty-foot-container equivalents (TEUs), ranking first among GCC members.23 Second-placed Saudi Arabia reached 11 million TEUs in 2013, but with stronger and more consistent annual growth than the UAE.

The other Gulf country with a trade surplus in services is Bahrain, largely due to government services. The other GCC members all accrue service trade deficits, but with different strengths and weaknesses. Kuwait’s largest deficit is in travel, while Saudi Arabia’s is “other business services,” which encompasses legal, accounting, business consulting, and engineering services.24 Qatar produces a trade surplus on transport ($4 billion) but a deficit in most other categories, including travel (-$7 billion).25

Figure 7: Services Trade Balance of GCC states (%).

Source: OECD Data Explorer, “Balanced trade in services (BaTIS),” accessed October 15, 2025.

Table 1: Overall GCC Trade Balances in Services, 2023 (USD).

| Sector | Trade Balance (USD) |

| Transport | +11.95 billion |

| Manufacturing services on physical inputs owned by others | +2.03 billion |

| Travel | -969.8 million |

| Charges for the use of intellectual property n.i.e.26 | -1.1 billion |

| Personal, cultural, and recreational services | -2.2 billion |

| Maintenance and repair services n.i.e. | -2.92 billion |

| Insurance and pension services | -4.57 billion |

| Financial services | -4.64 billion |

| Construction | -6.95 billion |

| Government goods and services n.i.e. | -14.81 billion |

| Other business services | -22.58 billion |

| Telecommunications, computer, and information services | -25.85 billion |

| All services | -71.723 billion |

Source: OECD Data Explorer, “Balanced trade in services (BaTIS),” accessed October 15, 2025.

The Gulf’s Current Trade Policies

The data presented so far are the result not only of exogenous developments but also of intentional trade policy adopted by GCC governments to navigate economic imperatives and geopolitical constraints. This section describes the broad outlines of Gulf trade policies and how they resulted in the current situation.

Traditional Orientation to the West

The Gulf states have long maintained a strong orientation toward the U.S. and other Western economies, based on interlocking economic and political motives. Most GCC hydrocarbon exports are denominated in U.S. dollars, regardless of their destination.27

This arrangement supplies GCC countries with dollars that can then be spent on direct investments in, and imports from, the U.S.—including American arms—, as described above. The Gulf countries also remain tied to U.S. economy and American policy by pegging their currencies to the dollar.28 This further favors trade in U.S. dollars and therefore the U.S. economy, as it eliminates the currency risk commonly associated with foreign trade.

These factors continue to play a dominant role in Gulf politics. Indeed, in April, President Donald Trump toured the Gulf on the inaugural overseas trip of his second term, accompanied by announcements of spectacular deals.29 But the factors that have shaped the Gulf’s westward outlook are gradually being challenged. An increasingly uncertain U.S. security umbrella, the prospect of a U.S. economic crisis and dollar volatility, frustrations with the U.S. arms trade,30 the looming threat of a U.S.-instigated trade war, and the waning importance of the U.S. and Europe for Gulf economies have caused a more fundamental re-evaluation of trade relations.

Re-Orienting Economic Ties

As a consequence, trade policy in the GCC has been shaped by the desire not only to diversify Gulf industries away from hydrocarbon dependence, but to diversify trade relations too, through regional and global trade integration.31 Given the growing irrelevance of the WTO,32 this has taken the form of direct bilateral and multilateral agreements. As a regional free-trade area, the GCC has free trade agreements (FTAs) with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), Singapore, Pakistan, South Korea, and New Zealand. Some ongoing FTA talks have been moving slowly, such as the EU-GCC talks and the Australia-GCC talks (initiated in 2007). This has prompted the UAE, in particular, to move ahead with separate, bilateral Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements (CEPAs) with dozens of counterparts, including the European Union, India, Türkiye, Australia, New Zealand and South Korea.33 Oman, too, concluded a separate CEPA with India, in view of the lengthy and difficult GCC-India FTA negotiations.34

Recently, however, the GCC’s FTA efforts have been revived. Most significantly, at the trilateral ASEAN-China-GCC summit in May, China and the GCC agreed to fast-track their FTA negotiations,35 while ASEAN and GCC initiated talks for an FTA between the two blocs.36 The GCC has also revived talks over FTAs with two other key trade partners, namely Japan and the United Kingdom.37 In contrast, EU-GCC trade talks have remained difficult.38

The Gulf’s pivot to Asia/China

While the GCC states are casting a wide net of intensified global trade relations, Asia—and China in particular—is taking center stage. This is unsurprising: As outlined above, Asia accounts for about three quarters of the GCC’s hydrocarbon exports. China alone buys one fifth, and imports from China to the GCC are also surging. The ASEAN-China-GCC summit in May was only the latest manifestation of the GCC’s economic pivot to Asia and emerging markets more broadly. Possibly more consequential is the UAE’s accession to the BRICS bloc in 2024, along with Saudi Arabia’s participation as an observer. Full Saudi membership could have momentous effects on trade patterns with Asia and the decoupling from Western economies.

While the Gulf region was not part of the original Belt-and-Road-Initiative (BRI) corridors envisioned by the Chinese government at its launch in 2013, GCC governments have since become partners in various projects.39 These include Chinese investments in the UAE’s Khalifa and Jebel Ali ports and Kuwait’s Mubarak al-Kabeer port, petrochemical infrastructure in Saudi Arabia, and Oman’s Duqm port. Petrochemicals are a central concern both for China’s industrial sector and for its GCC suppliers, whose U.S. demand is endangered by Trump’s trade wars.40

These closer ties have been accompanied by a diversification of monetary and security relations with China. As Asia grows in economic and political importance compared to the U.S. and China rises to become the world’s largest oil importer, the GCC has adapted its trading rules.41 Saudi Aramco signed an oil agreement with China that settles sales in yuan,42 Qatar became the first GCC country to launch a yuan clearing hub in 2015,43 and China made its first-ever yuan-denominated LNG purchase from the UAE in 2023.44 While these efforts are still in their infancy, they are gathering momentum amid growing economic and monetary uncertainty surrounding the U.S. and Trump’s erratic trade policies. It is becoming easier to envisage a shift in at least some GCC trade from the dollar to local currencies as a result of developments such as the adoption of an alternative payment system to SWIFT,45 growing stockpiles of gold in GCC and Asian central banks, and the growing presence of Chinese banks in the GCC, particularly in the UAE.46 This is flanked by a diversification of security alliances to lessen the dependence on the U.S., with accession to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, as well as efforts to revive security cooperation within the GCC.47

Intra-GCC trade integration has resulted in a customs union (established in 2003) and a common market (2008), harmonizing external tariffs and trade regulations among member states to facilitate intra-regional trade. However, regulatory hurdles remain. Efforts to launch a common GCC currency stalled in 2008 as a result of concerns about national sovereignty, and the common GCC patent office suspended new applications in 2021. Regional cooperation has been hampered by internal geopolitical tensions, such as the 2017-2021 Qatar blockade, and economic rivalry among states—especially between Saudi Arabia and the UAE—as exemplified by the struggle over the locations of regional corporate headquarters.48 However, there are signs of significant improvements in intra-GCC relations in recent years, which could in turn facilitate greater integration, such as the pending launch of a regional tourism visa.

There are also long-standing efforts to extend regional cooperation beyond the GCC, for example with the Greater Arab Free Trade Area Agreement (GAFTA), initiated in 1997. However, most initiatives regarding regional integration remain uncoordinated. Oman, for instance, is in talks to abolish mutual tariffs with Iran,49 the UAE’s DP World is expanding its port networks in India and Pakistan,50 while Saudi Arabia’s NEOM is positioning itself as a Euro-Asia logistics hub.51 A concerted, GCC-wide effort would bring more bargaining power and economies of scale to these efforts.

Trade-Supporting Policies

The new millennium has seen several bouts of intensive efforts to develop non-oil sectors to increase the added value of Gulf exports—albeit, as we have seen, with mixed success. This has included manufacturing, logistics, and services, supported by policies that promote foreign direct investment and ease of doing business.52 Policy reforms have

also aimed to align Gulf standards with international ones and improve regulatory frameworks to attract investment and foster innovation. In this context, establishing special economic zones (SEZs) has had trade-friendly effects.53 This pertains not only to explicitly trade-oriented SEZs (especially ports like Jebel Ali), but also financial and industrial SEZs that attract foreign business. Similarly, industrial policies that foster the transition from crude oil to downstream products and natural gas have had major effects on trade patterns.54

Policy Recommendations

As we have seen, GCC states have made many efforts as individual countries and as an economic bloc to diversify and integrate. These efforts can be intensified and built upon. Many trade policies need to be tailored to countries’ specific situations. For example, as described above, Bahrain and Oman struggle with extreme dependence on a single import partner. Indeed, all GCC countries depend, to varying degrees, on a handful of trade partners. A comprehensive policy agenda that aims to develop the GCC trade network, therefore, needs to integrate direct trade policies with appropriate supporting policies, recognize and align with existing policies, and leverage existing global logistics and re-export infrastructure. To achieve this, the GCC should adopt the following four recommendations in a concerted manner.

1. Revive the stagnating transition to non-hydrocarbon exports

As the data above shows, while certain GCC states have made some progress in reducing the importance of hydrocarbons in their exports, the share of fuels in the dollar value of export revenues, as well as the volume of oil exported, has remained mostly constant for the past decade. Moreover, the top merchandise categories where Gulf states have a revealed comparative advantage are still mostly hydrocarbon-related (either directly or downstream) or in traditional categories. In addition, a substantial share of exports, especially those of the UAE, consists of re-exports, with little to no value added locally.55

Current diversification strategies, therefore, need to be revisited and their effectiveness assessed. Gulf governments could develop more structured, state-led approaches to industrial policy, echoing the rise of the East Asian economies.56 Instead of the heavy industries (steel, cars, shipbuilding etc.) of Japan, South Korea, and China, GCC countries could concentrate on a modernized version centered around industries like defense and pharmaceuticals. Flanking existing efforts on national champions and high-tech start-ups, the GCC should also take clues from global models of successful, export-leading SME ecosystems. For instance, the Gulf could develop a regional version of “Mittelstand” firms—export-oriented SMEs that are global niche market leaders thanks to specialization and R&D, modelled on German companies like Kärcher and Sennheiser.57 Finally, such a push into industrial policy will necessitate major upgrades in state capacity, with competent ministries and agencies, similar to Japan’s MITI and Singapore’s EDB.

2. Strengthen regional trade relations

Despite the introduction of a GCC customs union and common market, intra-GCC trade has lagged behind expectations. This is due to lingering regulatory and other non-tariff barriers, a lack of differentiation between Gulf countries—because of their focus on hydrocarbon and hydrocarbon-adjacent sectors and their drives into the same post-oil niches—and intra-regional political and economic rivalries. Meanwhile, regional trade integration beyond the GCC, while underway, suffers from a lack of coordination.

Most importantly, the Gulf states must move beyond their economic rivalries by actively coordinating their industrial strategies to cultivate distinct areas of comparative advantage. Rather than duplicating investments in similar sectors, such as tourism, logistics, and finance, they should identify and specialize in unique niches, thereby reducing destructive competition and fostering complementary growth. In parallel, intra-GCC logistics infrastructure needs to be developed further.58 A renewed commitment to a comprehensive regional freight and passenger rail network would not only streamline the movement of goods and people, but also deepen economic interdependence and reduce logistical bottlenecks. Further, eliminating intra-GCC non-tariff barriers remains a priority. This requires harmonizing standards, simplifying customs procedures, and enhancing regulatory transparency to facilitate seamless trade flows within the bloc.

Finally, the GCC should pursue a concerted strategy to advance broader regional integration. By collectively engaging with neighboring economies such as Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, and India, and leveraging frameworks like BRICS and the BRI, the GCC could secure diversified trade partnerships and greater economic resilience.

3. Increase Self-Sufficiency

One of the most significant recent trends in GCC trade is the increasing dominance of Chinese imports into the GCC economies. In addition, events like Covid-19 and the Israel-Iran war have emphasized the need to develop national and regional self-sufficiency and supply chain resilience.

Policies to this effect would combine export promotion with import substitution, as demonstrated by successful ventures in Qatar, like Baladna in dairy (developed during the blockade) and Barzan Holdings in defense manufacturing.59 These initiatives exemplify how nurturing domestic champions can simultaneously bolster self-sufficiency and expand export capacity. Secondly, while imports from China are to some extent desirable and inevitable, policies should aim to locate significant parts of the value chain inside the GCC, notably through capital goods and knowledge transfer with China by fostering joint ventures. Projects such as Oman’s Karwa Motors illustrate how strategic partnerships can embed advanced manufacturing capabilities locally, reducing reliance on imports while leveraging Chinese expertise.60 Finally, supply chain diversification can be enhanced, for example, by establishing GCC-EU supply chain pacts for critical minerals and technology. In parallel, establishing GCC-wide buffer stocks of essentials like grains and pharmaceuticals would further insulate the GCC from supply shocks.

4. Reduce the large deficit in trade in services

The ambition of advancing to a post-oil “knowledge economy” remains unresolved. This is especially visible in the large service trade deficits in the UAE with respect to IT and telecommunications services, and in Saudi Arabia with respect to business services. To some extent, these deficits can be seen as stemming from capacity-building efforts that will result in diminished future dependence, such as investments in domestic IT and AI infrastructure and services, as well as temporary projects like NEOM. More recently, Saudi Arabia has cut its expenditure on consultancy services, in light of persistent difficulties in stemming the fiscal deficit and a sharp downsizing of mega- and giga-projects.61

Some policies are already providing the foundation for reducing the region’s services trade deficit. They include expanding digital infrastructure and supporting the export of GCC-based services, particularly in fintech, logistics, and creative industries. For example, Bahrain, with its comparatively low real estate and wage costs, has carved a niche in the GCC as a business process outsourcing and call center hub.

To reduce the deficit further, GCC countries need to prioritize the development of local talent and firms in high-value service sectors such as IT, telecommunications, and business services. First, targeted investment in education, vocational training, and incentives for domestic startups would help replace imported expertise in these sectors with homegrown capacity. Second, fostering technology transfer and joint ventures with leading global service providers could accelerate skills acquisition and the creation of regional service champions, as has been seen in certain IT and engineering partnerships. Finally, the GCC should redouble efforts to relocate multinational service firms’ regional headquarters and R&D centers through regulatory reforms and incentives.

Conclusion

The GCC’s trade networks remain in a dual tension, between hydrocarbon realities and post-oil aspirations, and between U.S. and Western geopolitical imperatives and a rising Asia. Existing efforts to use trade policy to diversify both industries and trade partners have shown some results. But as we have seen, the share of fuel exports has not declined significantly in the last decade, and China is quickly becoming the dominant exporter to the GCC even as economic and geopolitical constraints keep the bloc tied to the U.S.A. A new set of trade policies should focus on reviving intra-GCC and wider regional trade, strengthening economic self-reliance, creating a more qualitative relationship with China that enables joint ventures and knowledge transfer to move value creation to the Gulf, and a push to onshore key services like IT, professional, and financial services.

More generally, the current account balance does not stop at trade policy. An integrated strategy should also revisit approaches toward foreign direct investment, both incoming (with growing challenges highlighted by NEOM’s failure to attract sufficient foreign investment) and outgoing (such as Gulf Sovereign Wealth Funds funneling large sums to global investments). It should also look at transnational wealth transfers, both in terms of remittances (foreign workers in the Gulf send home some of the largest flows of remittances in the world) and wealth injections by high- and ultra-high-net-worth individuals into the Gulf. Efforts should include encouraging both these groups to keep their money in the Gulf and spend it there, instead of just “parking” it in real estate. This could best be achieved through residence, citizenship, labor, and foreign business ownership reforms. A broader strategy could also include revisiting infrastructure policy, industrial policy—for example, by strengthening the focus on SMEs and industrial R&D—and monetary policy. More careful thought needs to be spent on a well-rounded, multipronged strategy that coordinates various economic policies to further the goal of a post-oil society.