Gulf SMEs and the Post-Oil Economy:

Lessons from the Mittelstand Model

Policy Paper, September 2025

Abstract

Gulf governments’ strategies for their post-oil economies tend to emphasize the very big (mega- and giga-projects, and large corporations as national champions) and the very new (tech start-ups). While both are important ingredients in a post-hydrocarbons business ecosystem, they are not sufficient on their own. This article outlines the critical role that can be played by a specific kind of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)—Mittelstand companies or “Hidden Champions”—and suggests policies to develop this important layer.

Global economic leaders from Switzerland to Taiwan have not succeeded solely by focusing on national champions and high-risk start-ups, but through long-term strategies of nurturing stable, innovative and reputable SMEs that combine global leadership in their niches with high-wage, high-value-added employment. Such “Hidden Champions” are a vital component of the larger economy.

While Gulf states have promoted domestic SMEs in various ways, these firms remain less productive than their global peers. Appropriate industrial policy can nurture high-powered Mittelstand-like SMEs by providing critical financial, physical, intellectual, and human capital for these businesses, as well as promoting changes in business culture.

Key Recommendations

Provide Financing: While Gulf SMEs can access financing instruments, they remain underserved, particularly by private banks. For a healthy Mittelstand-like SME ecosystem, Gulf governments need to provide specialized banking and advice geared towards building and supporting “Hidden Champions.” This could be built on their existing development banks.

Cultivate and Harness Productive Human Capital: Mittelstand firms’ human capital needs are best served by complementary academic and practical skills. A dual-track education system could integrate apprentices and “work students” into local SMEs to train a skilled workforce for long-term, high-value-added employment relationships.

Provide Targeted Support: Gulf governments could employ a three-pronged approach of best practices, combining the creation of regional Mittelstand clusters around innovation hubs, like Germany’s Fachhochschule universities and dual-track high schools; research and development grants and incentives to invest in physical and human capital; and a strategy that harnesses the region’s comparative advantages, to incentivize family-owned conglomerates to “pivot to production.”

Retain Global Talent: The long-term relationship between Mittelstand firms and their employees needs stability, especially in a context dominated by foreign labor. GCC states could develop policies to keep valued non-citizen workers from leaving due to contract or visa restrictions, or lack of avenues to obtaining citizenship.

The Gulf’s Industrial Transition

As the Arab Gulf states transition away from reliance on hydrocarbons and seek to diversify their economies, governments are fostering industries that complement the oil sector, like mid- and downstream industries, logistics and increasingly, sectors less related to hydrocarbons, like tourism and finance. This pivot is underpinned by a digital transformation. “Vision” documents such as Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 and the UAE’s Centennial 2071 explicitly tie it to the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), which aims to harness AI, automation, and smart manufacturing to increase labor productivity.

This transition goes beyond changing the sources of national income. It also seeks to move citizens from public-sector to private-sector employment, through monetary incentives and mandated employment quotas, and to foster an interest in entrepreneurship—for example through incubators (e.g., Qatar’s Digital Incubation Center),1 SME funding vehicles (e.g., Saudi Arabia’s Kafalah program), and national campaigns promoting start-up culture. Yet these measures often clash with ingrained realities, like a private sector skewed toward low-wage migrant labor, risk-averse business cultures, and educational systems misaligned with industrial needs.

While widely publicized success stories like Noon Academy2 (Saudi edtech) or Souqalmal3 (UAE fintech) abound, they mask a broader stagnation: Real per-capita GDP is languishing,4 citizen labor market participation remains an issue,5 and many “entrepreneurs” default to government-contracted freelancing rather than scalable innovation.6 This paper argues that part of the problem is the missing middle, a layer of “Hidden Champions” that has long been neglected in favor of headline-grabbing flagship ventures and the risky hunt for the next start-up unicorn.

The Cost of Focusing on “Shiny Things”

The Arab Gulf’s business landscape is characterized by two extremes. At one end, colossal government-backed enterprises like Saudi Aramco, DP World, and Qatar Airways dominate strategic sectors, embodying a development model rooted in centralized capital, vertical integration, and geopolitical ambition. These entities mirror the quest for size by giga-projects (such as Saudi Arabia’s NEOM, Dubai’s large-scale terraforming, and Kuwait’s plans for Madinat al-Hareer), designed to capture attention and signal transformative growth.7 At the other end is a venture-capital-fueled, nascent start-up ecosystem that has produced firms such as Careem, Talabat, Salla and Pure Harvest, and which promises agility and digital disruption, buoyed by sovereign fund investments and regulatory sandboxes.

However, fixating on the two most visible ends of the business spectrum misses the vital middle. National champions, while capitalizing on scale economies, can become stagnant, too-big-to-fail whales with outsized political influence—as became apparent in South Korea, where chaebol conglomerates became a huge liability during the Asian financial crisis.8 Start-ups, on the other hand, often follow fads like the metaverse, the hyperloop, or non-fungible tokens (NFTs), with short-term exit strategies. They lack the patient capital and longevity to provide the volume of stable, well-paid jobs for citizens that policymakers hope to achieve.9 The focus on megaprojects and start-ups comes at the expense of another type of business necessary for an innovative, resilient economy: SMEs capable of driving organic, innovation-led growth. With some exceptions, Gulf SMEs remain constrained by regulatory fragmentation,10 reliance on state contracts,11 a lack of specialized and high-value niches, and most of all, a narrow public concept of entrepreneurship that fixates on the Silicon Valley-type start-up.12

Gulf states can take inspiration from another kind of entrepreneurship, the German-speaking countries’ Mittelstand model.13 With its emphasis on niche market leadership, export orientation, a culture of embeddedness in local regions, long-term horizon, quality, and innovation, as well as deep relations with employees, suppliers, and customers, it offers a potential blueprint for bridging this gap—providing Gulf states can reconcile this model with their appetite for quick solutions. Mittelstand-type companies would not only substitute high-value-added industrial exports for hydrocarbons but also provide stable, highly productive employment.

Hidden Champions and Mittelstand SMEs

SMEs form the backbone of any thriving economy, contributing significantly to employment, innovation, and GDP growth.14 Among them, Mittelstand-style firms stand out as critical drivers of national competitiveness. These highly specialized, export-oriented SMEs hail from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland (the DACH region), but are increasingly emulated worldwide. They focus on excellence in niche markets and maintain long-term stability through family ownership and skilled labor. Unlike traditional small businesses, Mittelstand firms generate disproportionate economic value, sustain stable high-wage jobs (SMEs employ more than half of the German workforce),15 make up the bulk of DACH exports, invest disproportionately in R&D as well as physical and human capital, and enhance industrial resilience. Recognizing and nurturing such high-potential SMEs, rather than treating all small businesses as homogeneous, should be a priority for policymakers aiming to build a dynamic and sustainable business ecosystem.

| Table 1: Typical Characteristics of Mittelstand Hidden Champions | |

| Characteristic | Description |

| Size | Small to medium enterprise |

| Ownership | Privately held, family-owned |

| Decision-making | Unity of ownership, leadership, and liability |

| Structure | Flat, lean hierarchies, operational flexibility |

| Strategic horizon | Long-term orientation, sustainable growth |

| Location | Strong local/community roots, often in small towns |

| Market focus | Export-oriented, global |

| Product focus | Niche product specialization, often in manufacturing |

| Research & Development | High innovation/patent density |

| Financing | Self-funding (profit re-investment); credit-financed |

| Customer relations | Long-term, close collaboration with customers |

| Employee relations | Long-term employment; vocational/in-house training |

What is the Mittelstand?

While the DACH region’s best-known firms include global giants like Volkswagen, Siemens, and Allianz, the region’s smaller Mittelstand firms lead the world in specialized, high-value niches: 48% of all mid-sized world market leaders come from Germany,16 often holding global market shares of 70–90% in their segments.17 Koenig & Bauer, for example, has an 80% share of the global market for banknote printing machines, and Lantal Textiles a 65% share of seat fabrics for airliners.18 Other Mittelstand firms include Ravensburger (puzzles and games), Faber-Castell (writing instruments), and Sennheiser (headphones). Their leadership derives from their reputation for craftsmanship, quality and durability, combined with continuous innovation.

Unlike conventional SMEs, Mittelstand companies are globally competitive, frequently dominating niche markets. Typically focused on manufacturing and engineering, they combine tradition with innovation, prioritizing long-term stability and a reputation for quality over short-term profits. Often family-owned, they follow an ethos of “enlightened family capitalism” that is deeply locally anchored. Kärcher (cleaning tools), for example, has been based in the small town of Winnenden for 90 years.19

One hallmark of this model is its investment in human capital; employees often stay for decades, benefiting from extensive in-house training and a strong sense of shared purpose. A good example is Liebherr, which trains its skilled workforce in-house at the “Liebherr Academy.”20 Mittelstand firms also cultivate durable ties with customers, often collaborating to refine products and processes over generations, giving them a competitive advantage.

While they are typically medium-sized, some—such as household names Adidas and Bosch—have grown into large multinationals without losing their Mittelstand characteristics. Nor is the model limited to the DACH region or the manufacturing sector. Rather, the Mittelstand model primarily defined by the combination of craftsmanship with state-of-the-art technology and a business ethos built on long-term, global perspective, operational and production excellence, trust, and specialization.

High-performing Mittelstand firms are often described as “Hidden Champions.”[vi] With some exceptions, they usually remain “hidden” because they are small, specialized, and often sell to other businesses rather than the end consumer. Yet while they are easily overlooked, they are indispensable to the economy.

How Policy can Support Mittelstand-Like Firms

Governments play a decisive role in fostering Mittelstand businesses.22 Strategic procurement policies, such as prioritizing domestic high-tech suppliers in infrastructure projects, generate demand for their advanced products and services.23 Trade policy facilitates Mittelstand exports through trade missions, export incentives, and access to global supply chains.24 Infrastructure policy provides energy grids, transport networks, and digital connectivity, and creates local industrial clusters, allowing these firms to operate efficiently and integrate into global value chains.25 A stable, adaptive legislative and regulatory framework is equally vital; this includes tailored legal and liability structures like the German GmbH and KG, intellectual property protections, and fiscal instruments which incentivize apprenticing trainees and reinvesting profits in the business.

Innovation support funds like Germany’s Central Innovation Program for SMEs (ZIM)26 help by funding R&D, applied research clusters and public-private partnerships, supporting SMEs as they turn laboratory breakthroughs into commercial production.27 To overcome SMEs’ diseconomies of scale, governments can foster support industry networks where firms share knowledge and resources without sacrificing competitiveness.28 Policies that encourage generational succession—through tax incentives for family-owned businesses, or mentorship programs—help preserve institutional knowledge.29 Crisis resilience policies can help these firms withstand global shocks; these include supply-chain diversification grants, energy-security buffers, and “Kurzarbeit,” a kind of state-subsidized furlough.

The following section describes three specific policies, typical of the DACH industrial model, which play key roles in developing the human capital, innovation, and finance of a Mittelstand.

1. Vocational Education

Mittelstands’ emphasis on craftsmanship creates voracious demand for skilled labor that combines science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) knowledge with practical skills. The dual-track, vocational education system characteristic of the DACH region has coevolved with the Mittelstand model, creating a symbiosis between education and industry.30 Students divide their time between classroom learning at high schools and hands-on apprenticing at Mittelstand firms, gaining both theoretical knowledge and practical skills tailored to real-world industrial needs. This approach ensures a steady supply of highly skilled, workers trained in specialized trades, directly addressing the Mittelstand’s demand for technical excellence. By embedding apprenticeships into their operations, these firms cultivate readily employable high school graduates and loyal, long-term employees with firm-specific human capital.31 The system reduces search costs and skills mismatches, facilitates youth employment, and reinforces the Mittelstand’s culture of craftsmanship and innovation.

2. Higher Education for Applied Innovation

Traditional universities often under-provide research of practical relevance to local businesses or produce graduates lacking the skills that the market needs. By contrast, the DACH region’s Fachhochschulen (universities of applied sciences) extend the dual-track system into higher education, partnering with Mittelstand businesses to carry out applied R&D to tackle real-world production challenges.32 Professors and students often collaborate directly with companies on joint projects, with “Werkstudenten” (roughly, “work students”) working part-time at firms. This allows the companies to access specialized expertise and state-of-the-art facilities without maintaining costly in-house R&D departments. Additionally, Fachhochschulen produce graduates with both technical skills and commercial R&D experience, who often remain at the firms after they graduate.33

3. Public Banks for Mittelstand Finance

Family-owned Mittelstand firms typically eschew both public and private equity in order to retain control, avoid short-term investor pressure, and reinvest profits instead of distributing dividends. Rather, they rely on long-term credit. Yet this is unpopular with private banks, given the low margins and onerous due diligence involved. Public banks like Germany’s Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) fill that gap by providing long-term, patient capital in the form of low-interest loans, credit guarantees, and venture debt.34 These and similar financing instruments enable SMEs to invest and develop without sacrificing equity or control. Mittelstand banks also offer tailored solutions like energy-efficient retrofits and digital transformation, aligning financing with strategic industrial priorities.35 Regional public banks further complement this system, offering deep knowledge of the Mittelstand business model, the local environment, and long-term relationships with borrowers.

Limits of the Mittelstand

While the Mittelstand model offers a proven blueprint for successful SMEs, it also presents challenges, many of which are relevant to Gulf adaptation. Succession crises can plague family-owned firms.36 Over-specialization may backfire if firms fail to adapt to changing demands and technologies. Mittelstand firms’ focus on incremental improvement sometimes leaves them vulnerable to disruptive technologies.37 Their reliance on bank financing (rather than equity) can slow their growth. In the Gulf, such limitations would be compounded by constrained vocational talent pipelines and a focus on short-term returns.

Yet these hurdles are surmountable with adequate policies: generational handover incentives (tax breaks for family-to-family sales), diversification grants for SMEs in at-risk niches, and innovation vouchers to partner with AI/clean-tech start-ups. The Mittelstand model can succeed—provided decision-makers are aware of the needs of this kind of business and adjust their policies accordingly.

A Gulf Mittelstand?

The idea that SMEs could be a key economic driver for the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, necessitating dedicated government strategies, is not new.38 But while some progress has been made,39 Gulf SMEs lag behind their global peers in terms of economic output.40 One remedy for this deficiency would be an SME policy with a sharper focus on creating a specific Mittelstand segment, whose “Hidden Champions” invest disproportionately in domestic R&D and physical and human capital, provide high-paying jobs, and export high-value-added goods. These firms would provide productive private-sector employment, serve as long-term talent magnets for expatriates—given appropriate visa and residence policies—and boost the productivity of migrant workers.

The Gulf’s Mittelstand Potential

The region possesses many elements needed to cultivate its own Mittelstand-like ecosystem of such mid-sized, export-oriented, high-quality niche market leaders.41 With vast resources, modern infrastructure, and ambitious economic diversification plans, Gulf states could foster homegrown “hidden champions” in sectors such as advanced materials (leveraging existing expertise in petrochemicals), green tech (harnessing abundant renewables), or policy priorities like AgriTech and defense. The Gulf has two key advantages: a focus on the Fourth Industrial Revolution and digitalization, a transformation which has been a stumbling block for some German SMEs; and ongoing efforts to transform citizens into entrepreneurs through incentives and incubators, which could be modified to nurture Mittelstand-type ventures.

Existing SMEs Prove Viability

The GCC countries already have a rich ecosystem of SMEs, including many family-owned businesses.42 This is reflected in Forbes’ annual list of top Arab Family businesses, with diversified business conglomerates consistently dominating the list (89% in 2022).43 On the other hand, specialized industrial leaders barely registered on it. The business models of the Arab region’s diversified conglomerates focus on low-risk, asset-light ventures (e.g. trading, retail, and services), —a legacy of historic reliance on commerce and real estate. Yet, these family firms share key cultural traits with Mittelstand firms: long-term family stewardship, local market knowledge, and close customer relationships. With proper government support, many have the potential to pivot toward the high-value, specialized model.

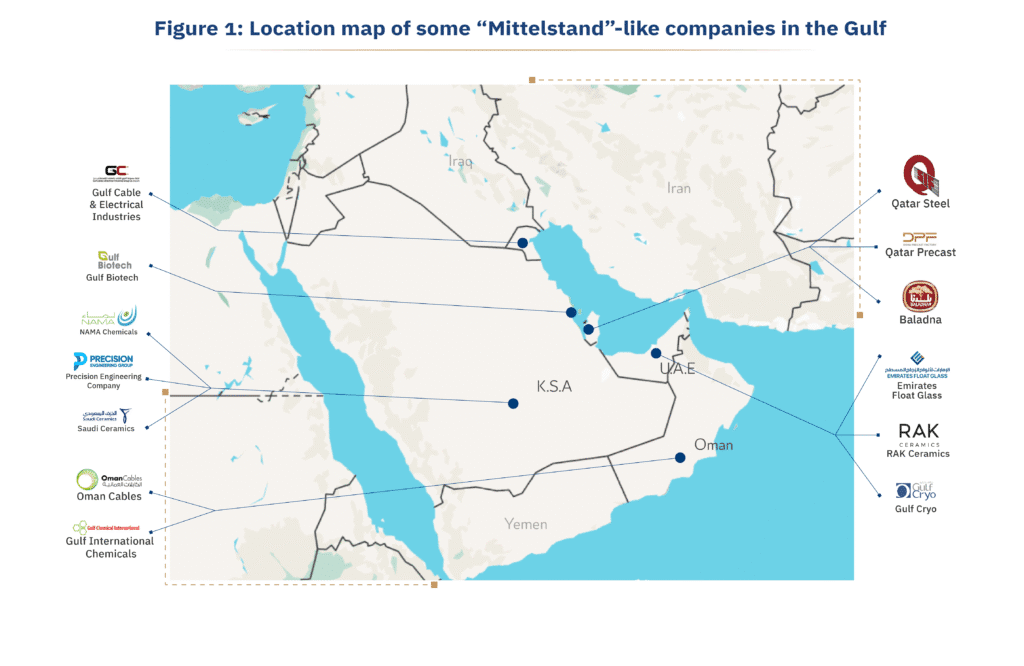

What is more, the Gulf is also home to some small- to mid-sized, export-oriented, innovation-driven, niche manufacturers that more closely resemble the Mittelstand model. Examples include Saudi Arabia’s NAMA Chemicals (specialty polymers) and Saudi Ceramics; Qatar’s mid-cap Qatar Steel, the UAE’s Gulf Cryo (industrial gases) and Emirates Float Glass; Oman’s Oman Cables and Gulf International Chemicals; Kuwait’s Gulf Cable & Electrical Industries; and Bahrain’s Gulf Biotech. Special cases include SMEs acting not as exporters but as domestic suppliers, like Precision Engineering Company (oil engineering services) and Qatar’s Baladna (dairy), which was conceived as an import substitution solution during the 2017 blockade. While some of these Hidden Champions have outgrown the SME label and are often not family-owned, they retain many Mittelstand qualities and demonstrate the viability and promise of a dedicated Gulf Mittelstand strategy.

Existing Policies and Institutions

While the GCC lacks a grand Mittelstand strategy, many initiatives exist that include support for SMEs. Saudi Arabia’s Strategy for Industry, the National Industrial Development and Logistics Program (NIDLP),44 the National Center for Family Business (NCFB), and the “Made in Saudi” initiative, while not dedicated to the “Hidden Champion” Mittelstand, are well-endowed industrialization and supply-chain localization programs that foster and promote domestic SMEs. Regulations also mandate that government projects source from local industrial SMEs.

Similar programs and regulations exist in the other GCC countries. The UAE’s federal “Operation 300bn” industrial development plan45 and National In-Country Value (ICV) Program are major localization efforts and are flanked by local strategies like Dubai Industrial Strategy 2030,46 which also offers subsidies for niche manufacturers. In Qatar, Manateq zones provide industrial SMEs with infrastructure for workshops and showrooms, the Tasdeer export promotion program helps Qatari manufacturers, and the 2022 World Cup provided ample demand for local SMEs such as SMEET Precast (precast concrete). Oman has its own ICV program and an industrial diversification program (Tanfeedh) that supports domestic manufacturing SMEs. Kuwait’s National Fund for SME Development and Bahrain’s Tamkeen similarly support local SMEs. Private financial institutions as well as state-owned development and export-import banks provide industrial credit and trade finance to domestic SMEs.

Peculiarities of the “Gulf Mittelstand”

Mittelstand-like firms in the Gulf show systematic differences from their DACH counterparts. As mentioned above, ownership structures differ; family-owned businesses tend to be non-manufacturing conglomerates while more Mittelstand-like SMEs are often state-owned, publicly traded (like NAMA Chemicals), or corporate subsidiaries. Another interesting model is Karwa Motors, an Omani bus manufacturer founded in 2017 as a joint venture between the Qatari state-owned Mowasalat company and the Oman Investment Authority, licensing technology from China. While not a Mittelstand-like company, its structure could provide a model for adapting the concept to Gulf peculiarities: the involvement of state-owned enterprises and sovereign wealth funds, the importance of knowledge transfer from outside the Gulf, and the need for GCC states to break down national borders and cooperate more closely.

The Gulf also has other characteristics that could hold back the drive to create Hidden Champions. The region’s private sector often prioritizes quick returns from trading, real estate, or low-value services over the long-term, patient capital required for industrial SMEs to mature into specialized quality leaders. As concerns human capital, the DACH’s dual-track vocational training model contrasts with the Gulf’s more traditional view of education as a purely academic endeavor, separate from the world of work. While flexible, reliance on expatriate labor on short, renewable contracts contrasts with the DACH model’s development of deep in-house skill and expertise to create a loyal, durable, locally rooted workforce that builds organizational knowledge and continuity. Additionally, the GCC Common Market has been less conducive to cross-border trade and business than initially hoped, with segmented labor markets and relatively low cross-border trade flows,47 contrasting with the way DACH Mittelstand firms operate fluidly within the European Union.

“Shiny Champions” and the Missing Middle

In other words, the Gulf Mittelstand exists but remains peripheral. To bring out its full potential, it must be nurtured through a coordinated strategy.48 The biggest hurdle to such a strategy lies in the Gulf’s policy and investment bias toward flagship projects—mega-projects like NEOM, tech start-ups chasing unicorn status in sectors subject to short-lived hype cycles, and state-backed national champions. The combination of attention seeking, short-termism, and a focus on equity markets and IPOs in the Gulf tends to divert attention and resources from the less glamorous, less immediately gratifying but equally critical SMEs that form the backbone of advanced economies. High-value industrial SMEs specializing in niche manufacturing, engineering, or materials science require patient and quiet nurturing. By fixating on scale, visibility, and immediacy—that is, on “shiny champions”—Gulf economies risk overlooking the “hidden” middle layer of firms that sustain long-term competitiveness through specialization, skilled employment, and incremental innovation.

Recommendations

Given these promising elements and substantial hurdles, how can the Gulf stimulate an innovative middle layer of Hidden Champions, and what can it learn from global models such as the DACH Mittelstand? Both the historic success and recent struggles of German mid-cap, innovative, exporting manufacturers are informative. They indicate that a successful Mittelstand strategy requires attention and long-term commitment as well as an integrated, holistic strategy that goes beyond mere industrial policy: a concerted effort including trade, education, research, finance, and infrastructure policy.

The Gulf could adapt the DACH Mittelstand model to the regional context but also take inspiration from other global SME successes. It could harness local comparative advantages while overcoming scale issues through regional integration. It could integrate and upgrade existing Gulf industrial policies and institutions, and embed Mittelstand-like SMEs into the economy while also attending to targeted priority sectors such as GreenTech, AgriTech, and defense, seeing the benefits of Mittelstand companies in a broader context than mere economic growth. Focus is key. Industrial programs like the Saudi NIDLP need to attend more to SMEs, while institutions that already cater to them, like the Qatar Development Bank, need to concentrate specifically on Mittelstand-like SMEs.

While the list of policy recommendations is long, this paper concludes with four key proposals, based on the most pressing, specific needs of Mittelstand-like SMEs:

1. Provide Financing

The GCC’s financial system as a whole favors large conglomerates and state-linked firms. “Relationship banking” and affordable, long-term loans for SMEs remain in short supply.49 To replicate the financial infrastructure underpinning Germany’s Mittelstands, Gulf countries should create dedicated Mittelstand banks. Given that the region already has national development banks—like Qatar Development Bank, which has financed more than 1,000 SMEs to date 50 —this recommendation presents low-hanging fruit.

Existing development banks could create dedicated in-house “Mittelstand Divisions.” Flanked by knowledge transfer from banks like the German KfW, this would provide targeted support to Mittelstand-like Hidden Champions and long-term, low-cost financing (including niche products like leasing and factoring) tailored to industrial SMEs for machinery, R&D, and export expansion, with grace periods aligned to production cycles, as well as zero-collateral innovation grants, succession planning, and anti-takeover minority stakes.

They could also offer risk-sharing guarantees to encourage private lenders to support niche manufacturers and serve as government-backed lenders of first resort.51 Modalities would ensure that funds are used efficiently and do not crowd out private credit, for example, with public-private co-financing arrangements. Ideally, a central Mittelstand bank would be complemented by a decentralized network of regional banks (similar to Germany’s Sparkassen, Raiffeisenbanken or Landesbanken) or by Swiss-style “guarantee cooperatives” which offer peer-to-peer finance, providing local expertise in lending decisions, and serve as a company’s “Hausbank” or “home bank.”

2. Cultivate and Harness Productive Human Capital

A Mittelstand-like ecosystem requires a workforce with both theoretical knowledge and practical skills. The DACH dual-track education system that combines high school education with on-the-job training could offer inspiration for nurturing such a workforce, followed up by higher education in the spirit of the Fachhochschule, which offers an excellent university education paired with work experience at companies. The Gulf could adopt and update Germany’s traditional apprenticeship model with its own Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) ambitions to make the system future-proof. Industrial SMEs that benefit from public contracts would be mandated to train locals in fields like mechatronics, additive manufacturing, and AI-aided design.

While applied degrees currently have a second-rate reputation, technical universities (such as Saudi Arabia’s KAUST, the UAE’s Khalifa University, and Qatar’s UDST) could partner with SMEs to design applied diploma programs, blending classroom and workshop learning to create highly desirable qualifications. Initial reluctance and bias towards purely academic degrees could be countered with wage premiums. An education system that produces highly employable, productive graduates would not only increase the private sector employability of Gulf citizens, but also help to upskill the non-citizen workforce, whose low productivity is another perennial policy concern.52

3. Provide Targeted Support

Gulf governments could harness their existing industrial policies and tailor them to encourage Hidden Champion SMEs through three key prongs. The first prong could harness Gulf experience with special economic zones to create innovation clusters specifically geared towards Mittelstand-type firms. For example, Qatari Manateq zones could be created as manufacturing clusters, centered around an education nucleus consisting of dual-track high schools and a Fachhochschule-type university, which provide human capital and R&D for the resident firms. Further inspiration could be sought from SME clusters like the watchmaking cluster in the Swiss Jura and government programs like the German “go-cluster”.53

The second prong would consist of horizontal policies open to all qualifying SMEs. This could encompass anything from modifying procurement quotas for state-owned enterprises to instead generate demand for local Mittelstand firms, to R&D support and export promotion. One such policy could offer incentives to existing family conglomerates that meet qualifying standards to move into manufacturing niches and become export-oriented, innovative quality leaders. Such a “Pivot to Production” package could include inducements to reinvest profits into industrial capital, legacy safeguards (allowing spin-offs of manufacturing units without losing family control), and subsidized industrial cluster zones with shared infrastructure and R&D facilities. Programs like this would tap into existing potential and transform established family firms into Gulf Hidden Champions.

Finally, Gulf governments should launch a program of more targeted support for existing Mittelstand-like SMEs, especially in priority sectors. These firms would receive tailored incentives and support for first-time export logistics, IP protection, and market intelligence. By focusing on firms with proven specializations, rather than generic small businesses, this program would accelerate the emergence of globally competitive Hidden Champions aligned with Gulf diversification goals. To avoid corruption, this program must be carefully designed, with an emphasis on transparency and accountability, including publicly communicated metrics, conditionalities, sunshine and sunset rules.

4. Retain Global Talent in the Long Term

The Gulf labor market thrives through its foreign labor, which is seen as transient or even precarious, with few protections and reliant on temporary contracts and visas. The current framework, which often ties residency to employment status and offers limited pathways to long-term settlement, creates uncertainty for skilled professionals and discourages them from building their careers and settling families in the region. This undermines SMEs, especially those modeled on the Mittelstand, which require a stable, long-term workforce to build the necessary in-house expertise for quality and innovation and to ensure generational knowledge transfer.

Policymakers should prioritize a comprehensive reform of labor, visa, and citizenship policies to retain highly skilled foreign workers. While the UAE has pioneered initiatives like the “golden visa,” most Gulf countries lag behind in offering clear, attractive settlement options. Evidence from Qatar and across the GCC shows that highly skilled migrants express a strong desire to remain, but are deterred by the lack of long-term security, family integration opportunities, and career planning prospects.54 To address this, Gulf governments should introduce multi-year, renewable residency permits that are independent of employer sponsorship, and offer transparent, merit-based pathways to permanent residency for skilled professionals and their families. Policies should also support family cohesion, allow for long-term employment contracts, easier job transitions, and offer social protections such as unemployment insurance, pension fund buy-ins, and longer post-termination grace periods.

Conclusion

Gulf SMEs lag behind their international peers in productivity. Overshadowed by more attention-grabbing ventures, they remain neglected by the public, financial institutions, and policymakers. Yet high-powered, Mittelstand-type SMEs could play a vital function for the region’s industrialization, economic stability and self-sufficiency. They could produce high-value-added exports and generate stable, well-paid private-sector jobs for citizens and skilled non-citizens alike. Moreover, a layer of such SMEs would support the ecosystem underpinning large national champions and high-risk start-ups. Redirecting policy energy toward these understated yet high-impact players could thus unlock complementarities and lead to more durable economic development.

This paper has outlined encouraging signs such as the existing examples of “native” Gulf Mittelstand firms, as well as identifying barriers that need to be overcome. It has enumerated several key lessons from the DACH Mittelstand model. Yet the Gulf need not replicate that model wholesale—instead, it can selectively blend insights from other global SME success stories, tailored to the region’s strengths. For example, the Italian region of Emilia-Romagna’s evolving approach, from the “Emilian Model” of the 1980s to “flexible specialization” and innovation clusters where SMEs collaborate (rather than compete) in shared supply chains, supported by local banks, vocational schools, and cooperative R&D: all this could be another inspiration for the Gulf.55

Another example is that of Taiwan’s electronics manufacturing SMEs, which thrived through tight university-industry R&D partnerships and export-focused industrial parks and exemplify a successful state-led industrial policy that may appeal to Gulf governments.56 Similarly, cultural models like Japan’s “monozukuri,” a focus on perfecting the product and mastering a craft, can be instructive. The end result could be a unique kind of Gulf Mittelstand that blends native qualities with global best practices.

To conclude with a concrete vision, one way to imagine the creation of a Gulf Mittelstand is through pilot clusters. These would build on existing Gulf expertise in creating special economic zones for industry, research, or both—and adapt them to the Mittelstand recipe. Such a cluster could be built around an educational core, consisting of dual-track high schools and a Fachhochschule-style university of applied sciences, deeply integrated with the surrounding industrial SMEs. These SMEs would be incentivized and supported to develop a Mittelstand ethos of locally-rooted, export-oriented niche-leadership, employing cluster-educated apprentices and “Werkstudenten,” and creating innovative high-quality products, in R&D partnerships with the cluster’s applied research institutions. The cluster would also feature supporting institutions, like a dedicated Mittelstand bank providing financial and business development services.

Endnotes

1 “Your Path to Startup Success Starts at DIC,” Direct Incubation Center, accessed May 15, 2025, https://dic.mcit.gov.qa/.

2 Aalia Mehreen Ahmed, “Saudi Unicorns: Saudi Arabia-Based Edtech Noon Education Is On A Mission To Make Quality Education Accessible Everywhere,” Entrepreneur Middle East, August 8, 2024, https://www.entrepreneur.com/en-ae/starting-a-business/saudi-unicorns-noon-education/478150.

3 “Souqalmal.com,” World Economic Forum, accessed May 18, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/organizations/souqalmal-com/.

4 Frederic Schneider, “Growth in the Gulf: Four Ways Forward,” LSE Middle East Center (Blog), July 22, 2021, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mec/2021/07/22/growth-in-the-gulf-four-ways-forward/.

5 Tim Callen, “Mixed Signals in the Latest Saudi Labor Market Report,” Arab Gulf States Institute, March 28, 2024, https://agsiw.org/mixed-signals-in-the-latest-saudi-labor-market-report/.

6 Crystal A. Ennis, “Rentier-preneurship: Dependence and autonomy in women’s entrepreneurship in the Gulf,” in POMEPS Studies 33: The Politics of Rentier States in the Gulf (Washington, DC: The Project on Middle East Political Science, January 2019), 60, https://pomeps.org/rentier-preneurship-dependence-and-autonomy-in-womens-entrepreneurship-in-the-gulf.

7 Frederic Schneider, “The Stalling Visions of the Gulf: The Case of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, March 14, 2021, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/stalling-visions-gulf-case-saudi-arabias-vision-2030.

8 Anne O. Krueger and Jungho Yoo, “Chaebol capitalism and the currency-financial crisis in Korea,” in Preventing currency crises in emerging markets, eds. Sebastian Edwards and Jeffrey A. Frankel (London: University of Chicago Press, 2002) 601, http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10645;

Sangin Park, “Chaebol reforms are crucial for South Korea’s future,” East Asia Forum, March 24, 2021, https://eastasiaforum.org/2021/03/24/chaebol-reforms-are-crucial-for-south-koreas-future/.

9 Frederic Schneider, “Tubes or Tracks: How (Not) to Revitalise Regional Economic and Political Integration in the Gulf,” LSE Middle East Centre (Blog), June 8, 2021, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mec/2021/06/08/tubes-or-tracks-how-not-to-revitalise-regional-economic-and-political-integration-in-the-gulf/.

10 GCC regulation is fragmented—most notably across borders, as member states set industrial policy largely independently of each other—but also within countries, especially across different special economic zones, which operate under different regulatory frameworks. Regulation can also change suddenly, as legislation is made by decree, see: Pratap John, “Open skies, harmonised regulations can unlock Middle East’s aviation potential,” Gulf Times, May 7, 2025, https://www.gulf-times.com/article/704295/business/open-skies-harmonised-regulations-can-unlock-middle-easts-aviation-potential; Alexios Zachariadis and Sally Hafez, “The road ahead: Autonomous vehicle manufacturing and adoption in the GCC,” Deloitte ME PoV, Spring 2025, https://www.deloitte.com/middle-east/en/our-thinking/mepov-magazine/next-generation-business/the-road-ahead-autonomous-vehicle-manufacturing-and-adoption-the-gcc.html; Pierrick Ribes, “The Barriers to Fintech and its Adoption in the Middle East,” Entrepreneur, March 5, 2025, https://www.entrepreneur.com/en-ae/growth-strategies/the-barriers-to-fintech-and-its-adoption-in-the-middle-east/488653.

11 The importance of government contracts depends on the industry. It is especially pronounced in infrastructure, healthcare, education, and SMEs catering to the government-owned hydrocarbon sector. In addition, the Gulf has a large share of state-owned and related enterprises, meaning that firms like Saudi Arabia’s Precision Engineering Company rely almost exclusively on government procurement contracts. The result is billions-worth of revenue stemming from public sources. No official statistics exist, but for examples: see: “Dubai SME facilitates AED1.29 billion in contracts to SME members of Emirati Supplier Programme in 2024,” Government of Dubai Media Office, June 16, 2025, https://mediaoffice.ae/en/news/2025/june/16-06/press-release-dubai-sme-facilitates.

12 Elizabeth Dwoskin, et al., “How the authoritarian Middle East became the capital of Silicon Valley,” Washington Post, May 14, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2024/05/14/middle-east-ai-tech-companies-saudi-arabia-uae/; Paul Cochrane, “Saudi Arabia’s digital dream: Silicon Valley for the Middle East,” Middle East Eye, April 4, 2023, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/saudi-arabia-digital-dream-build-silicon-valley-neom.

13 David B. Audretsch, “Have we oversold the Silicon Valley model of entrepreneurship?” Small Business Economics 56, no. 2 (February 2021): 849-856, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00272-4; Andre Pahnke and Friederike Welter, “The German Mittelstand: antithesis to Silicon Valley entrepreneurship?” Small Business Economics 52, no. 2 (February 2019): 345-358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0095-4.

14 Gilbert F. Houngbo, “MSMEs: The backbone of economies and the world of work,” International Labour Organization, June 27, 2023, https://www.ilo.org/resource/msmes-backbone-economies-and-world-work.

15 Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi), SMEs Digital: Strategies for the digital transformation. (Berlin, Germany: BMWi, July 2019), 4, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Publikationen/Mittelstand/smes-digital-strategies-for-digital-transformation.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1.

16 Hermann Simon, “Why Germany Still Has So Many Middle-Class Manufacturing Jobs,” Harvard Business Review, March 2, 2017, https://hbr.org/2017/05/why-germany-still-has-so-many-middle-class-manufacturing-jobs.

17 Hermann Simon, “Lessons from Germany’s Midsize Giants,” Harvard Business Review, March-April 1992, https://hbr.org/1992/03/lessons-from-germanys-midsize-giants.

18 Erik Fleischmann, “Wo das Geld gedruckt wird” [Where the money is printed], Forbes Austria, April 22, 2025, https://www.forbes.at/artikel/wo-das-geld-gedruckt-wird; Franz Schaible, “Textilhersteller Lantal plant eine zusätzliche Produktion im Ausland” [Textile manufacturer Lantal plans additional production abroad], Aargauer Zeitung, August 21, 2016, https://www.aargauerzeitung.ch/verschiedenes/textilhersteller-lantal-plant-eine-zusatzliche-produktion-im-ausland-ld.1575347.

19 Claus von Kutzschenbach, “Hochdruck am Markt” [High pressure on the market], Sales Business, June 2003, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF03226255; Bernd Venohr, Klaus Meyer, “Uncommon common sense,” Business Strategy Review 20, no. 1 (January 30, 2009): 38-43, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8616.2009.00578.x.

20 “Skilled workers are made,” Liebherr, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.liebherr.com/en-gb/group/magazine/liebherr-academy-rostock/liebherr-academy-rostock-4715590.

21 Hermann Simon, Hidden Champions of the Twenty-First Century: The Success Strategies of Unknown World Market Leaders (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press,1996).

22 Michael Holz, “Strategies and policies to support the competitiveness of German Mittelstand companies,” in Mid-sized Manufacturing Companies: The New Driver of Italian Competitiveness, eds. Fulvio Coltorti, Riccardo Resciniti, Annalisa Tunisini, and Riccardo Varaldo (Milan, Italy: Springer Milano, June 2013), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-88-470-2589-9_6.

23 Bernard Hoekman and Bedri Kamil Onur Taş, “Procurement policy and SME participation in public purchasing,” Small Business Economics 58, no.1 (2022): 383-402, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00414-z.

24 William E. Nothdurft, Going global: How Europe helps small firms export, (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, December 2010); OECD, Removing Barriers to SME Access to International Markets, Report (Paris: OECD Publishing, April 2008), https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264045866-en.

25 Hazel Davis, “The infrastructure SMEs need,” The Telegraph, March 12, 2019, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/challenges/sme-infrastructure/.

26 Heike Belitz, Alexander Eickelpasch, and Anna Lejpras, “Innovation policy for SMEs proves successful,” DIW Economic Bulletin 3, no. 4 (April 2013), https://www.diw.de/en/diw_01.c.419260.en/nachrichten/innovation_policy_for_smes_proves_successful.html.

27 Soogwan Doh and Byungkyu Kim, “Government support for SME innovations in the regional industries: The case of government financial support program in South Korea,” Research Policy 43, no.9 (November 2014): 1557-1569, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.05.001.

28 Mario Franco, Lurdes Esteves and Margarida Rodrigues, “Clusters as a Mechanism of Sharing Knowledge and Innovation: Case Study from a Network Approach,” Global Business Review 25, no.2 (April 2024): 377-400, https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150920957270.

29 Katsuyuki Kamei and Leo-Paul Dana, “Examining the impact of new policy facilitating SME succession in Japan: from a viewpoint of risk management in family business,” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 16, no.1 (2012): 60-70, https://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2012.046917.

30 Jorge Franch and Gemma Carmona, “The German business model: The role of the Mittelstand,” Journal of Management Policies and Practices 6, no.1 (2018): 10-16, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327322119_The_German_Business_Model_the_role_of_the_Mittelstand.

31 Klaus Schaack, “Why do German Companies Invest in Apprenticeship?” in International Handbook of Education for the Changing World of Work, eds. Rupert Maclean and David Wilson (Dordecht, Netherlands: Springer Dordescht, June 2009), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5281-1_118.

32 Alexander Starnecker and Katharine Wirsching, “The role of Universities of Applied Sciences in technology transfer: the case of Germany,” in Handbook of Technology Transfer, eds. David B. Audretsch, Erik E. Lehmann, and Albert N. Link (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2022), 159-175, https://ideas.repec.org/h/elg/eechap/20133_9.html/.

33 Julian Schenkenhofer and Dominik Wilhelm, “Fuelling Germany’s Mittelstand with complementary human capital: the case of the Cooperative State University Baden-Württemberg,” European Journal of Higher Education 10, no.1 (November 2019): 72–92, https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2019.1694421.

34 Ulrich Hommel and Hilmar Schneider, “Financing the German Mittelstand,” EIB Papers 8, no.2 (June 2003): 52-90, https://www.eib.org/en/publications/eibpapers-2003-v08-n02.

35 Peter Klaus, “Die KfW Mittelstandsbank als Katalysator in der Mittelstandsfinanzierung,” [The KfW Mittelstandsbank as a catalyst in SME financing], in Praxishandbuch Mittelstandsfinanzierung: Mit Leasing, Factoring & Co. unternehmerische Potenziale ausschöpfen [Practical Handbook for SME Financing: Unlocking Entrepreneurial Potential with Leasing, Factoring & Co.], ed. Manfred Goeke (Wiesbaden, Germany: Gabler Verlag Wiesbaden, July 2008): 195-211.

36 Carsten Linnemann, Germany’s Mittelstand – an endangered species? Focus on business succession, research report (Frankfurt, Germany: Deutsche Bank, July 2007), https://www.dbresearch.com/PROD/RPS_EN-PROD/Germany’s_Mittelstand_%C2%96_an_endangered_species%3F_Foc/RPS_EN_DOC_VIEW.calias?rwnode=PROD0000000000435629&ProdCollection=PROD0000000000461135.

37 Tim Kraft, Linus Lischke, and Johann Kranz, “How are Mittelstand experiences navigating the digital transformation process? An exploratory study in Germany,” paper #13, presented at the 32nd European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS 2024), Paphos, Cyprus, 13-19 June 2024, https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2024/is_governance/track21_is_govern/13.

38 Steffen Hertog, Benchmarking SME policies in the GCC: a survey of challenges and opportunities, Research Report, (Brussels, Belgium: Eurochambres, November 2010), https://www.academia.edu/7471683/Benchmarking_SME_Policies_in_the_GCC_a_Survey_of_Challenges_and_Opportunities.

39 Leo-Paul Dana, Palalic Ramo, and Veland Ramadani, eds., Entrepreneurship in the Gulf cooperation council region: Evolution and future perspectives, (London: World Scientific Publishing, 2021);

Tarek Sultan, “5 reasons small businesses and startups are thriving in the Gulf,” World Economic Forum, Dec 18, 2024, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/12/5-reasons-small-businesses-and-startups-are-thriving-in-the-gulf/.

40 Vahram Stepanyan et al, Enhancing the Role of SMEs in the Arab World—Some Key Considerations, Policy Paper, (Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund, November 2019), https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/PP/2019/PPEA2019040.ashx.

41 I have tried to represent all GCC member states in the interest of completeness. However, Saudi Arabia and the UAE make up about 75% of the GCC’s population and GDP, which means that these countries will inevitably be somewhat over-represented.

42 Gareth van Zyl, “Family-owned businesses ‘make up 90%’ of UAE’s private sector,” Gulf Business, December 26, 2023, https://gulfbusiness.com/family-owned-businesses-make-up-90-of-uaes-private-sector/.

43 “Top 100 Arab Family Businesses 2022,” Forbes Middle East, September 2022, https://www.forbesmiddleeast.com/lists/the-top-100-arab-family-businesses/.

44 “National Industrial Development and Logistics Program,” Vision 2030: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, accessed May 29, 2025, http://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/explore/programs/national-industrial-development-and-logistics-program.

45 “Operation 300bn, the UAE’s industrial strategy,” U.AE: The United Arab Emirates’ Governmental portal, accessed May 29, 2025, https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/strategies-plans-and-visions/industry-science-and-technology/the-uae-industrial-strategy.

46 “Dubai Industrial Strategy 2030,” U.AE: The United Arab Emirates’ Governmental portal, accessed May 29, 2025, https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/strategies-plans-and-visions/industry-science-and-technology/dubai-industrial-strategy-2030.

47 Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, “Missed Opportunities and Failed Integration in the GCC,” Arab Center Washington DC, June 1, 2018, https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/missed-opportunities-and-failed-integration-in-the-gcc/.

48 Frederic Schneider, “Start-ups and SMEs: Key lessons for the GCC from global models,” Gulf International Forum, June 18, 2024, https://gulfif.org/start-ups-and-smes-key-lessons-for-the-gcc-from-global-models/.

49 Mark Townsend, “Uncertain Future For GCC SMEs,” Global Finance, July 8, 2020, https://gfmag.com/data/uncertain-future-gcc-smes/; “The $250 Billion Opportunity: Closing the GCC’s SME Financing Gap,” Channel Capital Advisors, accessed April 29, 2025, https://channelcapital.io/the-gccs-sme-financing-gap/; “Bridging the SME finance gap in the GCC,” Deloitte, May 17, 2022, https://www.deloitte.com/middle-east/en/services/consulting/perspectives/bridging-sme-gcc-finance-gap.html; Pietro Calice and Paolo Buccirossi, Competition in the GCC SME Lending Markets: An Initial Assessment (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2016), https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/219781478855303337/pdf/110152-WP-GCCKnowledgeNotesSeriesNov-PUBLIC.pdf; Stepanyan et al., Enhancing the Role of SMEs in the Arab World.

50 “Direct Financing,” Qatar Development Bank, accessed May 29, 2025, https://www.qdb.qa/en/financing-and-funding/direct-financing.

51 David Kern, “Lender of first resort,” Prospect Magazine, September 21, 2011, https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/essays/49526/lender-of-first-resort.

52 Steffen Hertog, “Why the GCC’s Economic Diversification Challenges are Unique,” LSE Middle East Centre (Blog), August 7, 2020, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mec/2020/08/07/why-the-gccs-economic-diversification-challenges-are-unique/; Schneider, “The Stalling Visions of the Gulf: The Case of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030,”.

53 Denis Maillat et al, “Technology District and Innovation: The Case of the Swiss Jura Arc,” Regional Studies 29, no. 3 (1995): 251–263, https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409512331348943; “The ‘go-cluster’ programme,” Clusterplattform Deutschland, accessed May 29, 2025,

https://www.clusterplattform.de/CLUSTER/Navigation/EN/NationalLevel/go-cluster/go-cluster.html; Matthias Kiese, “Regional cluster policies in Germany: challenges, impacts and evaluation practices,” Journal of Technology Transfer 44, no. 6 (December 2019): 1698–1719, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9589-5.

54 Françoise De Bel-Air, “As the Gulf Region Seeks a Pivot, Reforms to Its Oft-Criticized Immigration Policies Remain a Work in Progress,” Migration Policy Institute, December 5, 2024, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/gulf-region-gcc-migration-kafala-reforms; Ameena Almeer, Misba Bhatti, and Zahra Babar, “Qatar’s Policy Landscape and its Impact on Highly Skilled Migration,” Konrad-Adenauer Stiftung, March 3, 2025, https://www.kas.de/en/web/rpg/detail/-/content/highly-skilled-migration-to-the-gulf-states-how-do-gcc-countries-fare-in-the-global-competition-for-.

55 Santarelli, Enrico, “The Competitive Advantage of a Region: Industrial Districts in Emilia-Romagna,” in Industrial Agglomeration and New Technologies: A Global Perspective, eds. Masatsugo Tsuji, Emanuelo Giovannetti, and Mitsuhiro Kagami (Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing, February 2007), 247-267.

56 Tzong-Ru Lee and Irsan Prawira Julius Jioe, “Taiwan’s small and medium enterprises (SMEs),” Education About Asia 22, no.1 (Spring 2017): 32-34, https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/taiwans-small-and-medium-enterprises-smes/.