Gulf LNG in the Time of U.S. Tariffs:

Navigating Geoeconomic Turbulence amid Trump’s Trade War

Issue Brief, August 2025

Key Takeaways

Tariffs are pushing East Asian LNG customers toward the U.S.: The industrial impacts of Trump’s tariffs, alongside intense political pressures, are pushing major energy importers such as China, India, Japan and South Korea to purchase American—rather than Gulf—LNG, to narrow trade imbalances with the U.S.

Washington is pressuring East Asian countries to invest in U.S. energy infrastructure: The U.S. is pushing Taiwan, Korea and Japan to invest in a pipeline project in Alaska and in American LNG shipbuilding. Gulf states should keenly follow this, as Taiwan has displayed interest, but Japan and South Korea are skeptical about the pipeline project due to the likelihood of low returns. The U.S. has also banned Chinese LNG vessels from docking at U.S. ports, which will impact shipping routes.

The AI revolution requires nuclear-powered AI data centers in East Asia: East Asian nations’ commitment to Artificial Intelligence and mega chip cluster development will heavily impact their energy plans, as nuclear power will be needed to generate enough electricity to power AI data centers.

Future energy strategies of East Asian economies drive LNG sourcing plans: East Asian nations’ future energy plans should be at the core of the Gulf’s LNG export policies and diversification strategies. To avoid supply chain interruptions amid an evolving global LNG market, the Gulf will need to address demands for flexible conditions like short-term contracts without destination clauses.

Introduction: U.S. Tariffs Pressure Europe and Asia Under Trump 2.0

During his first term, U.S. President Donald Trump imposed tariffs—antidumping, countervailing and safeguard duties—on certain products. The U.S. Export Control Reform Act (ECRA) of 2018 was implemented in line with a ban on Chinese telecoms firm Huawei,1 reversing a decades-long liberalization of export controls by the U.S.2 This proved to be a prelude to semiconductor export controls implemented under the subsequent Biden administration. Over time, the tech war became the core of the trade war, and the Biden administration identified certain sectors of technologies critical to its digital and green transition (DX & GX) goals, in which the U.S. had fallen behind,3 proposing to hand out subsidies and enticing allies to invest in U.S. DX and GX, via new legislations (e.g. the Chips and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022).

Figure 1. U.S. Trade Balances with Major Trading Partners (Bn USD)4

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

During his second term, Trump has imposed a broader reciprocal tariff system, country by country,5 since “Liberation Day” on April 2, 2025. This has compelled targeted counterparts to come to the table for bilateral negotiations with the U.S. if they seek to avoid or reduce the tariffs—particularly in the areas of critical and emerging technologies—while closing trade imbalances through purchases of U.S. Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) or other exports, or by investing in the U.S. Trump had suspended reciprocal tariffs on countries excluding China, applying only baseline tariffs at 10% during the 3-month negotiation period. Most countries that have significant trade surpluses with the U.S. (Figure 1)—notably China, India, Japan, and South Korea—have held multiple rounds of negotiations with the U.S. Washington set a deadline of August 1, 2025 for a final decision on reciprocal tariffs, leaving trading partners to seek recourse either by counter-tariffs or further negotiations. Notably, Japan and Korea were both set to face 25% reciprocal tariffs starting from August 1, 2025, unless further agreements are reached.6 The EU,7 Japan,8 and South Korea9 agreed on a 15% baseline tariff for their exports to the U.S after prolonged negotiations. All three yielded to U.S. pressure to invest hundreds of billions of dollars into the U.S., promised to buy more LNG from U.S.-based suppliers, and promised to consider investing or participating in the Alaska LNG pipeline project. For its part, the EU has previously pledged to spend $750 billion to replace Russian gas and oil.10 Meanwhile, Japan is aiming to spend $200 billion to import or 5.5 Mtpa of natural gas for 20 years,11 and South Korea has set a target of $100 billion in LNG deals with the U.S. 12 This coincides with other variables—such as these three actors’ aim to diversify their LNG portfolios at a time when energy security concerns and supply chain risks are critical.

The U.S. Plays a Major Energy Role as Gulf LNG Projects Expand

Since the shale gas revolution in the 2010s, the U.S. has become the world’s largest producer and exporter of LNG,13 as well as the world’s third-biggest oil exporter (Figures 3 and 4). In 2024, energy exports accounted for 16% of U.S. exports.14 However, it has not been immune to turbulence in global energy markets. Geopolitically, the war in the Ukraine since 2022 has shifted the market in complex ways, as Russian gas was sanctioned by the U.S. but still sold to Europe (Figure 2),15 including through rerouting via China.16 Even U.S. allies Japan and South Korea continue to consume some Russian gas, despite the U.S. insisting that its allies should cease Russian LNG imports. Washington is also demanding that the should EU purchase U.S. LNG,16 while EU countries oppose a baseline 10% tariff similar to that demanded by the U.S. as a starting point in the agreements18 that the U.S. inked with the UK19 and China.20

Figure 2. Russian Gas Exports to the EU 27, 2022-2025, billion cubic meters (BCM).21

Source: “European LNG Tracker,” Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), February 2025, https://ieefa.org/european-lng-tracker.

Figure 3: U.S. Energy Exports by Destination Country (2024)22

Source: Ron Bousso, “Oil and gas got off easy on Trump’s Liberation Day: Bousso,” Reuters, April 3, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/oil-gas-got-off-easy-trumps-liberation-day-bousso-2025-04-03/.

Gulf countries have gone ahead with planned natural gas projects. Qatar plans to expand its North Field project, increasing LNG production capacity23 by 43% from 77 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) to 110 mtpa via an expansion set for completion by 2027.24 In the United Arab Emirates, the focus was on activating a low-carbon facility at Abu Dhabi’s Al Ruwais Industrial City, operating LNG export facilities on clean power, and utilizing AI and digitalization for greater efficiency. Ruwais LNG, operated by state energy firm ADNOC, is set to have a total capacity of 9.6 Mtpa. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia’s Aramco has been tapping unconventional (shale) gas in the Jafurah onshore gas field in the country’s Eastern Province, to meet rising local demand.25 The Jafurah field is poised to come onstream in 2025 and to yield 2 billion standard cubic feet per day (bcf/d), equivalent to 15.19 Mtpa, by 2030.26

Overall, new or expanded projects are poised to place the global LNG market in overcapacity, creating an “influenced” buyers’ market due to tariff pressures, in which low price and short distance to delivery may not be the most compelling factors.

U.S. Pressures on East Asia: LNG Purchases, Infrastructure and Shipbuilding

During Trump’s first term, major LNG-consuming countries—China, India, Japan and South Korea—each signed long-term contracts with the U.S. to stave off trade pressures and to diversify their LNG sources.27 Given this precedent, they had anticipated that under Trump’s second term, the U.S. would expect the same form of LNG purchases; indeed, the four main Asian LNG buyers faced such pressure in their initial meetings with Trump.28 While demand for LNG continues to grow among major Asian consumers such as China and India, suppliers are also in intense competition due to political pressures imposed by U.S. tariffs.29 The U.S. also underlined that U.S. LNG contracts vary in duration and offer flexibility, as they do not have destination clauses30 or bans on third-party sales, unlike traditional long-term contracts, particularly with Qatar or Australia.

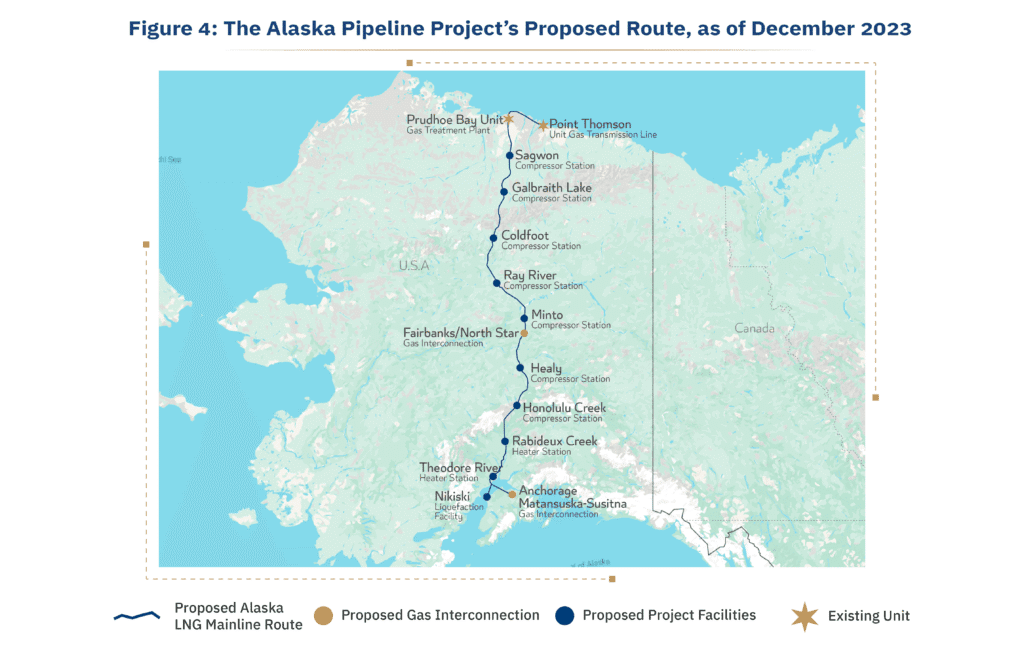

Prior to retaking office, Trump pressured East Asian countries to invest in the Alaska Pipeline Project. Officials from the Alaska Gasline Development Corporation (AGDC) and its development partner Glenfarne Group visited Taiwan, South Korea and Japan to generate interest in the project. Alaska has traditionally been a Republican state and a Trump stronghold.31 While it ranks fifth in the U.S. in terms of dry natural gas withdrawals (approximately 3.5 trillion cubic feet annually)32 from some 125 trillion cubic feet of reserves, they are reinjected back into oil reservoirs to help maintain crude oil production rates, due to the lack of a pipeline to transport the natural gas to consumers in southern Alaska or for export.33 The $44-billion project in which the Trump administration has pressed Taiwan, South Korea and Japan to invest is an infrastructure project rather than an LNG project, aiming to build a 807-mile pipeline connecting Prudhoe Bay (where the gas treatment plant is located) to the Nikiski in the south of Alaska (Figure 4). From there, Alaskan LNG could be shipped to Asia with an estimated delivery time of seven days to Japan and eight to South Korea, bypassing the Panama Canal and using a direct route across the Pacific Ocean.

Figure 4. The Alaska Pipeline Project’s Proposed Route, as of December 202334

Source: Dragana Nikše, “Alaska’s LNG project moves closer to reality after 10 years in the making, with Glenfarne as private investor,” Offshore Energy, January 10, 2025, https://www.offshore-energy.biz/alaskas-lng-project-moves-closer-to-reality-after-10-years-in-the-making-with-glenfarne-as-private-investor/. Regenerated on ArcGIS.

The project had received a U.S. federal loan guarantee35 for $30 billion from the Department of Energy, via Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act,36 with a proposed completion year of 2030 or 2031, but the remainder of the required investment had yet to be secured at the time of writing. The project has been regarded as lacking feasibility. During Trump’s first term in office, China’s state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), its sovereign wealth fund the China Investment Corporation (CIC), and its central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), had signed a Joint Development Agreement on LNG with the U.S. in November 2017, with a proposed investment of $43 billion), under pressure from the first Trump administration to cut U.S. trade deficits. However, they had exited the project by 2019 due to fears of low returns.37

In March 2025, Taiwan, seeking energy security and vulnerable to China, sought a deal with the U.S. and indicated its intent to purchase $200 billion worth of goods (including LNG) from the U.S.38 Taiwan’s state-owned petroleum company CPC signed a letter of intent (LOI) to invest in the project.39 Taiwan also said it would send a delegation to the Alaska Sustainable Energy Summit hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy in June 2025.40 Japan and South Korea also face intense pressures to invest in the Alaska pipeline project for LNG distribution and export,41 but the Alaska project has had a bad track record; both countries appear skeptical toward the project.42 Officials from Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) and JERA attended the Alaska Summit. JERA submitted an expression of interest in the project, offering financial and technical contributions including investment, in order to smooth tariff talks, but without specifying how much LNG it intends to buy.43 Officials from South Korea’s Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) and state-owned natural gas firm KOGAS also attended the Alaska Summit. The U.S., aware of the Japanese desire for Trump’s green light for Nippon Steel’s acquisition of U.S. Steel, has been soliciting Japanese investment in the Alaska pipeline project and calling for the use of Japanese steel.44 South Korea has previously formed joint ventures to develop LNG in Alaska in 198445 and 2020,46 under U.S. pressure, which have not led to concrete results.

Cognizant of South Korea’s prowess in shipbuilding and the waning of its own shipbuilding industry,47 the U.S. has called for South Korean ship-makers to build U.S. LNG carriers in the U.S., as well as naval ships.48 Such developments are the result of regulatory shifts aiming to counter China’s ascent in the maritime, logistics and shipbuilding sectors. The also U.S. plans to charge Chinese vessels to dock in U.S. ports.49

The AI Revolution Shaping East Asian Energy Plans and LNG Diversification

According to the IEA, the AI revolution will double energy demand by 2030 (compared to current demand).50 AI is at the heart of East Asian nations’ energy planning, in tandem with their net-zero goals. Powering and maintaining AI data centers will require an exponential increase in electricity supply, as reflected in the UAE’s recent announcement that it would launch an AI campus with a 5GW power capacity.51 For East Asian players that seek to boost their chip production by building clusters or expanding foundries, an expanded electricity supply is all the more vital. However, countries vary in terms of their energy sources for power generation, depending on where they see strengths and weaknesses in their energy mixes. This in turn affects the degree to which they need to diversify their LNG portfolios.

Japan’s “7th Strategic Energy Plan,” covering the period until 2040, signals an expansion of nuclear power and renewable energy sources to fit the country’s net-zero goals (Figure 5).52 The plan has faced criticism for being unrealistic, as Japan currently runs 12 nuclear reactors—far short of the 27 needed to achieve its goals.53 While Japan’s LNG demand is projected to fall, it is seeking to secure consistent procurement of the fuel, under flexible terms. In 2017, the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) ruled that destination restrictions that prevent the reselling of contracted LNG cargoes breached antitrust rules,54 leading JERA and Tokyo Gas to renegotiate some contracts with LNG suppliers.55 JERA is currently negotiating a long-term contract to buy 3 mtpa from QatarEnergy.56 Japan’s LNG portfolio is somewhat diversified.57 The country conducted rounds of negotiations with Washington, with the goal of having U.S. tariffs removed on Japanese autos, car parts, steel and aluminum. It remains unclear how much U.S. LNG Japan will commit to buying, but Japan has pledged a $550 billion investment into the U.S. along with the signing by JERA for a $200 billion LNG deal. It is notable that given the absence of destination clauses in the U.S. LNG contracts, Japan has been building its status as a gas hub with sales to third countries in Southeast Asia.

Figure 5. Japan’s Energy Plan from 2022 to 2040, kilowatt-hours (kWh)58

Source: Outlook for Energy Supply and Demand, The 7th Strategic Energy Plan, Agency of Natural Resources and Energy of Japan, February 2025.

Note: The projections for 2040 are based on the average of the maximum and minimum estimates from the Agency of Natural Resources of Japan.

Figure 6. Japan’s LNG Imports 2023-2024, as of February 2025 (mtpa).59

Source: John Geddie, Tim Kelly and David Brunnstrom, “Trump seeks to reshape Asia’s energy supplies with US gas,” Reuters, February 22, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/trump-seeks-reshape-asias-energy-supplies-with-us-gas-2025-02-21/

South Korea’s 11th Basic Plan for Long-Term Electricity Supply and Demand (BPLE) until 2038 projects a major shift on how it will deliver energy for its tech industries (chips, batteries, display, biotech, future cars and robotics sectors) and for powering for AI data centers (Figure 7).60 In particular, the Yongin Chip Cluster (1.4 GW), data centers (4.4 GW) and electrification of transportation and daily life (11 GW) will lead to unprecedented usage of electricity, which will be met by nuclear and renewables, in line with the goal of meeting net-zero and energy efficiency targets. Two new nuclear reactors are set to be deployed between 2037-2038 (2.8GW), and for the first time, a 0.7-GW small modular reactor (SMR) will be deployed by 2036, with the possibility of further deployment.61

Figure 7. South Korea’s Energy Plan, 2024 to 2038: Future Energy Mix by Terrawatt hour (tWh)62

Source: Cha Dae-woon, “Mutanso jeongi daebi 11cha jeongibon hwakjeong… 2038nyeon wonjeon 35%·jaesaeng 29% (무탄소 전기 대비 11차 전기본 확정…2038년 원전 35%·재생 29%) [The 11th electric power base for carbon-free electricity has been confirmed… 35% nuclear power and 29% renewable power plants by 2038],” Yonhap News Agency, https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20250221070600003.

South Korea has been importing 9 Mtpa of LNG from Qatar and exporting LNG vessels to the country.63 In November 2024, QatarEnergy officials visited Seoul and Tokyo to meet counterparts at KOGAS (Korea Gas Corporation) and JERA, to emphasize their partnership while anticipating renewal of the long-term contracts with Korean and Japanese parties leading up to long-term contractual expiry. 64 In the meeting with KOGAS, QatarEnergy insisted on retaining the destination clauses. In December 2024, KOGAS shortlisted BP, Trafigura and TotalEnergies for a 2.1-mtpa long-term LNG contract and has reportedly signed several heads-of-agreements (HOAs), covering amounts, pricing structure, supply periods and handover methods in long-term contracts, with U.S. LNG suppliers.65

In July 2021, KOGAS signed a 2 Mtpa LNG contract with QatarEnergy for 20 years (2025-2044),66 but South Korea’s existing long-term LNG contracts with Qatar—for 2.02 Mtpa in 2025 and 2 Mtpa in 2026—are likely to lapse, given the country’s focus on diversification of its LNG portfolio. South Korea will seek new sources of LNG by shifting to U.S. suppliers, as the country still relies on the Gulf for 36% of its total LNG imports67 and seeks further diversification (Figure 8). South Korea exhibits a standard case in which lapsing contracts are replaced by U.S. LNG, in an effort aimed at minimizing the impact of U.S. tariffs on its core industries such as autos and chips.

Figure 8. South Korea’s LNG Portfolio, 2009-2023 (mtpa)68

Source: Korea Energy Economics Institute (KEEI), based on Michelle (Chaewon) Kim, “Three reasons the U.S. LNG pause does not threaten South Korea’s energy security and transition,” Institute For Energy Economics And Financial Analysis, February 21, 2024, https://ieefa.org/resources/three-reasons-us-lng-pause-does-not-threaten-south-koreas-energy-security-and-transition.

China’s ambitious future energy plan includes huge solar and wind projects as well as nuclear generation (Figure 9). The country has one of the world’s biggest AI data centers, contributing to soaring electricity demand. There is no doubt that China will continue consuming LNG, but it has stopped purchasing it from the U.S. since February 6. 69 Given the trade war between the U.S. and China, particularly over AI chip export controls, it is not clear whether the two countries will reach an agreement resembling the Phase 1 Deal reached in 2020. Since then, China has diverted to the UAE, reaching a 5-year LNG supply agreement with ADNOC.70 China already has a very diversified LNG portfolio and consumes Russian Piped Natural Gas (PNG), so sourcing does not appear to be a problem, were negotiations with the U.S. to fail (Figure 10).

Figure 9. China’s Energy Plan, 2025 to 206071

Source: Emily Pontecorvo, “Can China go net-zero? Two charts show just how ambitious Xi Jinping’s goal is,” Grist, October 2, 2020, https://grist.org/climate/can-china-go-net-zero-two-charts-show-just-how-ambitious-xi-jinpings-goal-is/; based on Bloomberg News, “China’s Top Climate Scientists Plan Road Map to 2060 Goal,” September 28, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-09-28/china-s-top-climate-scientists-lay-out-road-map-to-hit-2060-goal?sref=wINQCNXe.

Figure 10. China’s LNG Import Portfolio, 2015-2025 (mtpa)72

Source: Kpler, cited by Ron Bousso, “US risks losing long game in China LNG spat,” Reuters, February 6, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/us-risks-losing-long-game-china-lng-spat-bousso-2025-02-06/.

India has been an important player in the Gulf LNG market—importing primarily from Qatar. In contrast to Japan and Korea, whose trade policies in the past two decades were focused on reaching Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs), India only secured its first FTA with a western economy (the United Kingdom) in June 2025. It completed the fifth round of talks on a Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) with the U.S. in the shadow of U.S. tariffs73 but could not reach an agreement on replacing Russian gas, with India arguing for its diplomatic posture towards Russia.74 The sticking points in the negotiation are on agriculture and automobiles, and the key goal for India has been to remove the additional 26% of tariffs and reduce duties on steel and aluminum (currently at 50%) and autos (25%). Top Indian LNG importers sought to buy more LNG from U.S. suppliers in the lead-up to the Trump-Modi summit in Washington, D.C. in February.75 This reflected a trend of Asian players and the EU purchasing more U.S. LNG to offset trade imbalances with the U.S. and to defend themselves against Trump’s tariffs. While more than half of India’s LNG imports derive from the Gulf (Qatar, UAE, Oman), it has been increasing its LNG purchases in the past two years (Figure 10).

Figure 11. India’s LNG Portfolio, 2023-2024 (mtpa)76

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution (HS Code 271111: Natural gas, liquefied), the World Bank, https://wits.worldbank.org/trade/comtrade/en/country/IND/year/2023/tradeflow/Imports/partner/ALL/product/271111

Adapting to the Changing LNG Market and Pricing amid the Trade War

Since the shale gas revolution, LNG spot markets have emerged, alongside a continued trend of long-term contracts in the form of SPAs (Sale and Purchase Agreements). With the geopolitical impact of the Ukraine War on LNG supply chains, various forms of LNG SPA are emerging as traditional long-term contracts lapse.77 It has dawned upon East Asian countries that long-term contracts do not necessarily ensure lower prices (see Figure 13.1, the case of Japan, where prices of LNG from the UAE and Qatar have been the highest). This has created a rush to replace lapsing long-term contracts in various ways. That is particularly true in South Korea, which has seen a domestic debate over the relative high price it pays for Gulf LNG compared to other East Asian destinations, including China, due to the failure to predict demand—or because purchases are bound to long-term contracts (see Figures 13.2 and 14).78 Against this backdrop, and adding to the falling price of natural gas and LNG prices in the past year (2024-2025) consistent with the continuing trend of natural gas price falls (Figure 12), East Asian players will maneuver towards various options.79 In light of tariffs, East Asian players are likely to prefer short, flexible, unbundled LNG SPAs (without destination clauses).

Figure 12. Global LNG Prices, 2014-2023 (USD/MBtu)80

Source: Korean Public Data Portal, “hanguggaseugongsa_hangug-ui wolbyeol cheon-yeongaseu su-ibhyeonhwang mich biyong jungdong” 한국가스공사_한국의 월별 천연가스 수입현황 및 비용 중동 [Korea Gas Corporation_Korea’s Monthly Natural Gas Imports and Costs Middle East],” accessed June 5, 2025, https://www.data.go.kr/data/15102983/fileData.do.

Figure 13. Japanese and South Korean Import Prices81

Source: “Tennen Gasu ・ LNG Dēta Habu 2025 (天然ガス・LNGデータハブ2025) [Natural Gas and LNG Data Hub 2025], JOGMEC, accessed June 4, https://oilgas-info.jogmec.go.jp/ebook/dh2025/.

Figure 14. Asian Market LNG Import Prices During the Ukraine War (USD/MBtu)82

Source: Korean Public Data Portal, “hanguggaseugongsa_asiagug LNG su-ibdanga 한국가스공사_중국 PNG 수입단가 [Korea Gas Corporation_China PNG import unit price],” accessed June 5, 2025, https://www.data.go.kr/data/15117763/fileData.do?recommendDataYn=Y.

LNG markets are likely to witness overcapacity in the coming years.83 More than 70 mtpa of net contracted capacity will expire by 2030.84 In the current climate of trade war and their respective ongoing bilateral negotiations with the Trump administration, it is difficult to gauge how major East Asian buyers will vary in terms of the amounts and terms in their contractual agreements for U.S. LNG purchases. But it is evident that they seek to secure the best possible deals and minimize the impact of tariffs, by pushing for arrangements that will fit their interests based on their future energy plans. It is highly likely that the preference for term contractual arrangements with buyer protection against shortfalls will prevail over maintenance of long-lasting business relationship. On this point, Gulf states should consider flexible provisions in future contracts to keep Gulf LNG attractive, given the impact of Trump’s tariffs on their Asian customer base—that is, China, Japan and South Korea.

Endnote

1 Donald Shepardson and Karen Freifeld, “Trump administration hits China’s Huawei with one-two punch,” Reuters, May 16, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/business/trump-administration-hits-chinas-huawei-with-one-two-punch-idUSKCN1SL2QX/

2 Paul K. Kerr and Christopher A. Casey, The U.S. Export Control System and the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 (Washington, D.C.:U.S. Congressional Research Service, 2021), https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46814.

3 The White House, Building Resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American Manufacturing, And Fostering Broad-Based Growth: 100-Day Reviews under Executive Order 14017, (Washington, D.C.: The White House, 2021), https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/100-day-supply-chain-review-report.pdf.

4 “U.S. Trade in Goods by Country,” United States Census Bureau, accessed June 5, 2025, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/.

5 “Executive Order 14257: Regulating Imports with a Reciprocal Tariff to Rectify Trade Practices that Contribute to Large and Persistent Annual United States Goods Trade Deficits,’” The White House, April 2, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/04/regulating-imports-with-a-reciprocal-tariff-to-rectify-trade-practices-that-contribute-to-large-and-persistent-annual-united-states-goods-trade-deficits/.

6 Jong-moon Choi, Dong-Won Jung, Jeongju Jahng, Kwang-Wook Lee, Keun Woo Lee and Hye Jin Woo, “Han-mi gwansehyeobsang hyeonhwang-gwa gieob daeeung jeonlyag (한-미 관세협상 현황과 기업 대응 전략) [Current Status of Korea-U.S. Tariff Negotiations and Corporate Response Strategies],” Yoon & Yang LLC / Lexology, July 16, 2025. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=87d8f3e7-1c03-4c61-ad56-c8fd6888d495.

7 ‘EU-US trade deal explained,’ EU Commission, Brussels, July 29, 2025. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_25_1930.

8 “Bei-koku no kanzei sochi ni kansuru nichibei kyōgi: Nichi-bei kan no gōi (米国の関税措置に関する日米協議:日米間の合意) [Japan-U.S. Consultations on U.S. Tariff Measures: Agreement between Japan and the U.S.],” Naikaku kanbō kanzei jimukyoku (Japan Cabinet Secretariat Customs Bureau), July 22, 2025 https://www.meti.go.jp/tariff_measures/pdf/2025_0725_02.pdf.

9 “hanmi gwansehyeobsang tagyeol…sanghogwanse 25%→15%, jadongcha·bupum 15% (한미 관세협상 타결…상호관세 25%→15%, 자동차·부품 15%) [Korea-US tariff negotiations reached… reciprocal tariffs reduced from 25% to 15%, with 15% for automobiles and parts],” Daehanmingug jeongchaegbeuliping (Republic of Korea Policy Briefing), July 31, 2025. https://www.korea.kr/news/policyNewsView.do?newsId=148946888.

10 “US LNG producers climb as EU agrees to $750 billion in energy purchases,” Reuters, July 29, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-lng-producers-climb-eu-agrees-750-billion-energy-purchases-2025-07-28/

11 “JERA Announces Milestone Agreements with U.S. Partners to Secure Up to 5.5 Million Tonnes of New Long-Term LNG Supply Annually over 20 Years,” Press Release, JERA, June 12, 2025. https://www.jera.co.jp/en/news/information/20250612_2184; Note: JERA, which stands for “Japan Energy for a New Era,” is a 50-50 joint venture between TEPCO Fuel & Power and Chubu Electric Power established in April 2015, following the Fukushima nuclear incident.

12 Hong Jung-kyu, “gwansetagyeol: han, daegyumo tuja·eneoji gumaelo il·EUwa dongdeunghan gwanse hwagbo (관세타결] 韓, 대규모 투자·에너지 구매로 日·EU와 동등한 관세 확보) [Tariff Settlement: South Korea Secures Tariffs on Par with Japan and EU Through Large-Scale Investments and Energy Purchases],” Yonhap News, July 31, 2025. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20250731044000071.

13 Anna Shiryaevskaya, “Qatar LNG Exports Shrink from Record as Australia, U.S. Expand,” Bloomberg, April 8, 2015. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-04-07/qatar-lng-exports-shrink-from-record-as-australia-u-s-expand

14 “United States Exports By Category,” Trading Economics, 2024, accessed July 25, 2025, https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/exports-by-category.

15 Kate Abnett, “How could the EU ban Russian gas?” Reuters, May 16, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/how-could-eu-ban-russian-gas-2025-05-16/; Anna Hirtenstein and Marwa Rashad, “Exclusive: US, Russia explore ways to restore Russian gas flows to Europe, sources say,” Reuters, May 8, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-russia-explore-ways-restore-russian-gas-flows-europe-sources-say-2025-05-08/.

16 Jo Harper, “Is China reexporting Russian gas to Europe?” Deutsche Welle, September 16, 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/is-china-reexporting-russian-gas-to-europe/a-63146922.

17 “US LNG supplies to Europe will continue to rise, says US Energy Secretary,” Reuters, April 28, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-lng-supplies-europe-will-continue-grow-says-us-energy-secretary-2025-04-28/.

18 Camille Gijs and Koen Verhelst, “EU won’t accept UK-style tariff deal with Trump, ministers say,” Politico, May 15, 2025, https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-wont-accept-uk-china-style-tariff-deal-with-trump-ministers-say/.

19 “General Terms For The United States Of America And The United Kingdom Of Great Britain And Northern Ireland Economic Prosperity Deal,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, May 8, 2025, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/Press/fs/US%20UK%20EPD_050825_FINAL%20rev%20v2.pdf.

20 “Joint Statement on U.S.-China Economic and Trade Meeting in Geneva,” The White House, May 12, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/05/joint-statement-on-u-s-china-economic-and-trade-meeting-in-geneva/.

21 “European LNG Tracker,”; Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), February 2025, https://ieefa.org/european-lng-tracker.

22 Ron Bousso, “Oil and gas got off easy on Trump’s Liberation Day: Bousso,” Reuters, April 3, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/oil-gas-got-off-easy-trumps-liberation-day-bousso-2025-04-03/.

23 Nikolay Kozhanov, “Qatar’s LNG expansion plans and the issue of market oversupply,” Middle East Institute, May 21, 2024, https://mei.edu/publications/qatars-lng-expansion-plans-and-issue-market-oversupply; “H.E. Minister Saad Sherida Al-Kaabi Announces Raising Qatar’s LNG Production Capacity To 142 Mtpa Before The End Of 2030,” QatarEnergy, February 22, 2024, https://www.qatarenergy.qa/en/MediaCenter/Pages/newsdetails.aspx?ItemId=3799; “North Field East Project, Qatar,” Offshore Technology, July 2022, https://www.offshore-technology.com/projects/north-field-expansion-project/; Verity Ratcliffe and David Stringer, “Qatar to Build New LNG Project as US Stalls on Export Push,” Bloomberg, February 25, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-02-25/qatar-to-accelerate-lng-expansion-as-us-stalls-on-export-push?embedded-checkout=true; Claudia Carpenter and Stuart Elliott, “Infographic: Qatar’s vast LNG expansion,” S&P Global Commodity Insights, August 30, 2023, https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-research/latest-news/lng/083023-infographic-qatar-expands-gas-imports-globalisation-china-india-southkorea-pakistan.

24 “Qatar National Vision 2030,” Qatar Free Zone, accessed July 25, 2025, https://qfz.gov.qa/why_qatar/qatar-national-vision/.

25 “Unconventional resources,” Aramco, accessed December 29, 2022, https://www.aramco.com/en/what-we-do/operations/unconventional-resources.

26 “Aramco says Jafurah Gas Plant phase 1 to come on stream in 2025,” Zawya, March 5, 2025, https://www.zawya.com/en/projects/oil-and-gas/aramco-says-jafurah-gas-plant-phase-1-to-come-on-stream-in-2025-q19c5vop.

27 “Natural gas and LNG Data Hub: III. LNG,” JOGMEC, accessed July 25, 2025, https://oilgas-info.jogmec.go.jp/nglng_en/datahub/dh2025/1010409.html.

28 John Geddie, Tim Kelly and David Brunnstrom, “Trump seeks to reshape Asia’s energy supplies with US gas,” Reuters, February 22, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/trump-seeks-reshape-asias-energy-supplies-with-us-gas-2025-02-21/.

29 “U.S. liquefied natural gas exports quadrupled in 2017,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, March 27, 2018, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=35512#:~:text=Exports%20to%20South%20Korea%20accounted,of%20total%20U.S.%20LNG%20exports; “Trump touts big energy deals in Asia,” BBC, November 14, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-41967171.

30 Ayesha K. Waheed and Hiroki Kobayashi, “LNG for Japanese Buyers: End of the Road for Destination Clauses?” Latham & Watkins LLP / Lexology, July 17, 2017, https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=c1aef7be-f8be-4750-873c-d1009b8e096b.

31 “Recent Presidential Elections – Alaska,” 270 to win, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.270towin.com/states/alaska.

32 “Alaska Dry Natural Gas Production,” U.S. Energy Information Agency, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.eia.gov/dnav/ng/hist/na1160_sak_2m.htm.

33 “Alaska Profile – State Profile and Energy Estimates,” U.S. Energy Information Agency, accessed May 15, 2025. https://www.eia.gov/state/analysis.php?sid=AK.

34 Dragana Nikše, “Alaska’s LNG project moves closer to reality after 10 years in the making, with Glenfarne as private investor,” Offshore Energy, January 10, 2025, https://www.offshore-energy.biz/alaskas-lng-project-moves-closer-to-reality-after-10-years-in-the-making-with-glenfarne-as-private-investor/.

35 “LNG In World Markets: Alaska LNG to Tap US Loan Guarantee as it Targets SPAs,” Poten & Partners, December 2022, https://agdc.us/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/LNGWM-Alaska-LNG-Report.pdf

36 U.S. Department of Energy, “Loan Guarantees for Clean Energy Projects: A Rule by the Energy Department,” Federal Register, May 30, 2023, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/05/30/2023-11104/loan-guarantees-for-clean-energy-projects.

37 Sungbin Im and Minjoong Kim, “8 nyeonjeon jung-gug-eun bal ppaessneunde…’allaeseuka LNG’ hangugseo 64 jo seiljeu 8 (년전 중국은 발 뺐는데…’알래스카 LNG’ 한국서 64조 세일즈) [China backed out 8 years ago…’Alaska LNG’ 64 trillion won sold in Korea],” Joongang Daily, March 19, 2025, https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/25321980.

38 Ben Blanchard and Faith Hung, “Taiwan could buy $200 billion more from US, increase LNG imports as part of trade deal,” Reuters, April 10, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/taiwan-says-trump-tariff-pause-gives-breathing-room-more-detailed-talks-2025-04-10/.

39 “Ālāsījiā zhōuzhǎng 3 yuè fǎng tái cù tóuzī fēijī yī luòdì zhōngguó jiù kàngyì (阿拉斯加州長3月訪台促投資 飛機一落地中國就抗議) [Alaska governor visits Taiwan in March to promote investment; China protests as soon as plane lands],” Central News Agency (CAN)中央通讯社, May 13, 2025, https://www.cna.com.tw/news/aipl/202505130015.aspx.

40 Miaojung Lin, Yian Lee, and Yvonne Man, “Taiwan Will Send Delegation to Alaska LNG Talks Next Week,” Bloomberg, May 29, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-05-29/taiwan-will-send-delegation-to-alaska-lng-talks-next-week.

41 “US seeks to convene Japan, South Korea for LNG summit in Alaska,” S&P Global Commodity Insights, April 25, 2025, https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-researc…seeks-to-convene-japan-south-korea-for-lng-summit-in-alaska.

42 “Japan gas industry head says higher US LNG imports must be mutually beneficial,” Reuters, March 19, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/japan-gas-industry-head-says-higher-us-lng-imports-must-be-mutually-beneficial-2025-03-19/; River Davis and Sylvan Lebrun, “U.S. Allies in Asia Snub Natural Gas From Alaska Project,” The Wall Street Journal, July 25, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/world/u-s-allies-in-asia-snub-natural-gas-from-alaska-project-e54f754a.

43 Yoshiaki Nohara, “Japan Touts Ships Expertise, LNG Project as Tariff Talks Key,” Bloomberg, May 26, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-05-26/japan-touts-ships-expertise-lng-investment-as-tariff-talks-key; Koh Yoshida and Tsuyoshi Inajima, “Japan’s Top LNG Importer Will Explore Buying From Alaska,” Bloomberg, May 30, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-05-30/japan-s-top-lng-buyer-inks-preliminary-pact-with-alaska-project.

44 “Nippon Steel to ‘heavily invest’ in US Steel rather than acquire it: Donald Trump,” Eurometal, February 10, 2025. https://eurometal.net/nippon-steel-to-heavily-invest-in-us-steel-rather-than-acquire-it-donald-trump/; “South Korea to send officials to Alaska energy conference, ministry says,” Reuters, May 29, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/south-korea-send-officials-alaska-energy-conference-ministry-says-2025-05-29/.

45 “Allaeseuka LNGgaebalcham-yeo 5 sa keonsosieom mosaeg (알래스카 LNG개발참여 5 사 컨소시엄 모색) [Seeking a 5-company consortium to participate in Alaska LNG development],” Maeil Economic Newspaper, February 17, 1984, https://www.mk.co.kr/news/economy/629752.

46 “[Dandog] hanmijeongsang hab-uihan allaeseuka cheon-yeongaseu gaebal, sasilsang musan (단독]한미정상 합의한 알래스카 천연가스 개발, 사실상 무산) [Exclusive: Alaska Natural Gas Development Agreed by Korea-US Summit, Virtually Falls Apart],” The Chosun Ilbo, October 20, 2020, https://www.chosun.com/politics/2020/10/20/QHPLRZBSENGJTHLGUX36QLFGMY/.

47 Lisa Baertlein and Jarrett Renshaw, “US energy companies seek exemption from Trump plan to move LNG on US-built ships,” Reuters, May 9, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-energy-companies-seek-exemption-trump-plan-move-lng-us-built-ships-2025-05-07/#:~:text=In%20a%20move%20that%20shocked,in%20April%202047%20and%20beyond.

48 “Regulatory Shift Prompts Hanwha Shipping to Construct LNG Carriers in the U.S.,” BusinessKorea, April 22, 2025. https://www.businesskorea.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=240544

49 “USTR Section 301 Action on China’s Targeting of the Maritime, Logistics, and Shipbuilding Sectors for Dominance,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, April 17, 2025, https://ustr.gov/about/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2025/april/ustr-section-301-action-chinas-targeting-maritime-logistics-and-shipbuilding-sectors-dominance.

50 “AI is set to drive surging electricity demand from data centres while offering the potential to transform how the energy sector works,” International Energy Agency, April 10, 2025, https://www.iea.org/news/ai-is-set-to-drive-surging-electricity-demand-from-data-centres-while-offering-the-potential-to-transform-how-the-energy-sector-works; see also: Laura Cozzi, et al., Energy and AI (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2025), https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai.

51 Abu Dhabi’s 10 square mile (25.9 square kilometer) AI campus will have 5 GW of power capacity, enough power to support 2.5 million Nvidia’s top-line B200 chips (see: Federico Maccioni, Manya Saini and Yousef Saba, “UAE to build biggest AI campus outside US in Trump deal, bypassing past China worries,” Reuters, May 16, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/uae-set-deepen-ai-links-with-united-states-after-past-curbs-over-china-2025-05-15/), while the Al Barakah Plant in the outskirts of Abu Dhabi has four APR-1400 nuclear reactors, each generating 1.4GW (all four units were on grid as of March 2024, totaling 5.6GW capacity (see: “ENEC connects to the grid the 1.4 GW Unit 4 of the Barakah nuclear plant (UAE),” Enerdata, March 26, 2024, https://www.enerdata.net/publications/daily-energy-news/enec-connects-grid-14-gw-unit-4-barakah-nuclear-plant-uae.html). The Emirates Nuclear Energy Company (ENEC) is poised to develop more nuclear power plants locally and internationally in the future (see: Dania Saadi, “UAE’s ENEC may develop more nuclear power plants locally, internationally in future,” S&P Global, March 3, 2022, https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-research/latest-news/electric-power/030322-uaes-enec-may-develop-more-nuclear-power-plants-locally-internationally-in-future).

52 Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (Japan), The 7th Strategic Energy Plan (Tokyo: Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, 2025), https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/others/basic_plan/pdf/7th_outline.pdf; “Japan’s 7th Strategic Energy Plan focuses on nuclear and renewables through 2040,” Enerdata, February 20, 2025, https://www.enerdata.net/publications/daily-energy-news/japans-7th-strategic-energy-plan-focuses-nuclear-and-renewables-through-2040.html.

53 Walter James, “Japan’s Seventh Strategic Energy Plan Is Both Unambitious and a Fantasy,” Energy Tracker Asia, March 31, 2025, https://energytracker.asia/japan-seventh-strategic-energy-plan/; Yuka Obayashi and Katya Golubkova, “Japan targets 40-50% power supply from renewables by 2040,” Reuters, December 17, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/japan-targets-40-50-power-supply-renewable-energy-by-2040-2024-12-17/.

54 “Ekikaten’nen gasu no torihiki jittai ni kansuru chōsa ni tsuite (液化天然ガスの取引実態に関する調査について) [Survey on the actual status of liquefied natural gas trading],” Japan Fair Trade Commission, June 28, 2017, http://www.jftc.go.jp/houdou/pressrelease/h29/jun/170628_1.html.

55 Ken Koyama, JFTC Views LNG Destination Restrictions as Likely to Have Antimonopoly Act Problems, Special Bulletin, (Tokyo: Institute of Energy Economics, Japan, 2017), https://eneken.ieej.or.jp/data/7431.pdf; Lauren Holtmeier and Hassan Butt, “More offtake agreements in pipeline for ADNOC’s Ruwais LNG project,” S&P Global Commodity Insights, June 11, 2024, https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-research/latest-news/natural-gas/071124-more-offtake-agreements-in-pipeline-for-adnocs-ruwais-lng-project; “Nuclear reactor restarts in Japan have reduced LNG imports for electricity generation,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, February 8, 2024, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=61386.

56 Marwa Rashad, Emily Chow, Yuka Obayashi and Maha El Dahan, “Exclusive: QatarEnergy in talks with Japan on long-term LNG supply deal,” Reuters, May 2, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/qatarenergy-talks-with-japan-long-term-lng-supply-deal-2025-05-01/.

57 “INTERVIEW: Japan hopes for 80% long-term LNG share post-2030, sees no issue with contracts beyond 2050,” S&P Global Commodity Insights, February 27, 2025, https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-research/latest-news/lng/022725-interview-japan-hopes-for-80-long-term-lng-share-post-2030-sees-no-issue-with-contracts-beyond-2050.

58 Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (Japan), The 7th Strategic Energy Plan.

59 John Geddie, Tim Kelly and David Brunnstrom, “Trump seeks to reshape Asia’s energy supplies with US gas,” Reuters, February 22, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/trump-seeks-reshape-asias-energy-supplies-with-us-gas-2025-02-21/

60 Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (of South Korea) “Je 11-cha Jeollyeok Sugeup Gibon Gyehoeg (2024–2038) Sujeong Gonggo (제11차 전력수급기본계획(2024~2038) 수정 공고) [Revision Announcement of the 11th Basic Plan for Long-Term Electricity Supply and Demand, 2024-2038],” 산업통상자원부 (Republic of Korea: Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy), March 13, 2025, https://www.motie.go.kr/kor/article/ATCLc01b2801b/70152/view.

61 “Mutanso jeongi daebi 11-cha jeongibon hwakjeong… 2038-nyeon wonjeon 35%·jaesaeng 29% (무탄소 전기 대비 11차 전기본 확정…2038년 원전 35%·재생 29%) [11th Basic Electricity Plan finalized in comparison to carbon-free electricity… 35% nuclear, 29% renewables by 2038],” Yeonhap News, February 21, 2025. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20250221070600003.

62 Cha Dae-woon, “Mutanso jeongi daebi 11cha jeongibon hwakjeong… 2038nyeon wonjeon 35%·jaesaeng 29% (무탄소 전기 대비 11차 전기본 확정…2038년 원전 35%·재생 29%) [The 11th electric power base for carbon-free electricity has been confirmed… 35% nuclear power and 29% renewable power plants by 2038],” Yonhap News Agency, https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20250221070600003.

63 “S Korea’s Kogas to import 1.58 mil mt/year US-produced LNG from BP,” S&P Global Commodity Insights Live, April 22, 2022, https://cilive.com/commodities/liquefied-natural-gas-lng/news-and-insight/042222-s-koreas-kogas-to-import-158-mil-mtyear-us-produced-lng-from-bp.

64 Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security, 32. JERA (Tokyo: Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security, 2024), https://oilgas-info.jogmec.go.jp/_res/projects/default_project/_page_/001/009/975/4_32_en_2024_jera.pdf.

65 “MiLNG doib gyeyag chujin… daemi muyeogheugja pog jul-igi (美LNG 도입 계약 추진… 대미 무역흑자 폭 줄이기) [Promoting US LNG import contract… Reducing trade surplus with the US],” Donga Ilbo, December 19, 2024, https://www.donga.com/news/Inter/article/all/20241219/130677888/2.

66 “2025-nyeon-buteo 20-nyeon-gan Katareu-san cheonyeon-gaseu yeon 200-man ton singyu do-ip, Daehanminguk Jeongchaek Beuriping (2025년부터 20년간 카타르산 천연가스 연 200만톤 신규 도입,” 대한민국 정책브리핑) [Starting in 2025, South Korea to newly import 2 million tons of Qatari natural gas annually for 20 years, Republic of Korea Policy Briefing],” Korea.kr, July 13, 2021, https://www.korea.kr/news/policyNewsView.do?newsId=148890059.

67 “Geullobeol LNG donghyang-gwa Miguk-ui LNG jeongchaek, gyeongje anbo(글로벌 LNG 동향과 미국의 LNG 정책, 경제안보) [Global LNG Trends and U.S. LNG Policy, Economic Security],” Ministry of Foreign Affairs (of South Korea), April 11, 2025.

https://www.mofa.go.kr/www/brd/m_26799/view.do?seq=369114&page=1

68 Michelle (Chaewon) Kim, “Three reasons the U.S. LNG pause does not threaten South Korea’s energy security and transition,” Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, February 21, 2024, https://ieefa.org/resources/three-reasons-us-lng-pause-does-not-threaten-south-koreas-energy-security-and-transition.

69 “Chinese imports of American LNG dry up as trade war rages,” Nikkei Asia, April 28, 2025, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Energy/Chinese-imports-of-American-LNG-dry-up-as-trade-war-rages.

70 Chen Aizhu, “China’s CNOOC agrees LNG deal with UAE’s Adnoc amid tariff war with US,” Reuters, April 22, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/chinas-cnooc-agrees-lng-deal-with-uaes-adnoc-amid-tariff-war-with-us-2025-04-21/.

71 Emily Pontecorvo, “Can China go net-zero? Two charts show just how ambitious Xi Jinping’s goal is,” Grist, October 2, 2020, https://grist.org/climate/can-china-go-net-zero-two-charts-show-just-how-ambitious-xi-jinpings-goal-is/.

72 Ron Bousso, “US risks losing long game in China LNG spat,” Reuters, February 6, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/us-risks-losing-long-game-china-lng-spat-bousso-2025-02-06/.

73 TOI Business Desk, “India-US trade deal: Fifth round of talks for BTA completed; both countries aim to finalise interim deal ahead of Trump’s tariff deadline,” Times of India, July 20, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/india-us-trade-deal-fifth-round-of-talks-for-bta-completed-both-countries-aim-to-finalise-interim-deal-ahead-of-trumps-tariff-deadline/articleshow/122777352.cms.

74 Jennifer A. Dlhouy, “Trump Vows to Ramp Up India Tariffs in Escalation of Russia Spat,” Bloomberg, August 4, 2025. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-08-04/trump-says-us-to-hike-india-s-tariffs-over-russian-oil-purchases.

75 Rakesh Sharma and Stephen Stapczynski, “India LNG Buyers Negotiate US Deals Before Modi-Trump Summit,” Bloomberg, February 10, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-02-10/indian-lng-buyers-negotiate-us-deals-ahead-of-modi-trump-summit.

76 World Integrated Trade Solution (HS Code 271111: Natural gas, liquefied), the World Bank, https://wits.worldbank.org/trade/comtrade/en/country/IND/year/2023/tradeflow/Imports/partner/ALL/product/271111.

77 Agnieszka Ason, International Gas Contracts, OIES Paper: NG 175, (Oxford: Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, 2022), https://www.oxfordenergy.org/publications/international-gas-contracts/.

78 Park Chan-gyun, “Cheonyeon-gaseu, iut gukga boda hwolssin bissan gagyeogeuro su-ip: Gaseu Gongsa, cheonyeon-gaseu suyoyegchuk silpaero jeokja wonin jegong (천연가스, 이웃 국가 보다 훨씬 비싼 가격으로 수입: 가스공사, 천연가스 수요예측 실패로 적자 원인 제공) [Natural gas imported at significantly higher prices than neighboring countries: Korea Gas Corporation’s failure to forecast demand cited as cause of deficit],” Today Energy, October 10, 2023, https://www.todayenergy.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=265200; Kim Jung-deok, “Mun jeongbu tasse LNG janggi gyeyak mothaetda? 3gaji waegokgwa namtat chujeok+ (文 정부 탓에 LNG 장기계약 못했다? 3가지 왜곡과 남탓 추적+) [Is it the Moon administration’s fault for failing to secure long-term LNG contracts? Three distortions and blaming others Investigation+],” The Scoop, November 11, 2024, https://www.thescoop.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=303832.

79 “Natural gas and LNG related information,” Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security, updated June 2, 2025, https://oilgas-info.jogmec.go.jp/nglng_en/index.html.

80 Korean Public Data Portal, “hanguggaseugongsa_hangug-ui wolbyeol cheon-yeongaseu su-ibhyeonhwang mich biyong jungdong (한국가스공사_한국의 월별 천연가스 수입현황 및 비용 중동) [Korea Gas Corporation_Korea’s Monthly Natural Gas Imports and Costs Middle East],” accessed June 5, 2025, https://www.data.go.kr/data/15102983/fileData.do.

81 “Tennen Gasu ・ LNG Dēta Habu 2025 (天然ガス・LNGデータハブ2025) [Natural Gas and LNG Data Hub 2025], JOGMEC, accessed June 4, https://oilgas-info.jogmec.go.jp/ebook/dh2025/.

82 Korean Public Data Portal, “hanguggaseugongsa_asiagug LNG su-ibdanga 한국가스공사_중국 PNG 수입단가 [Korea Gas Corporation_China PNG import unit price],” accessed June 5, 2025, https://www.data.go.kr/data/15117763/fileData.do?recommendDataYn=Y.

83 “IEEFA: Tidal wave of new LNG supply to flood market amid demand uncertainty,” Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, April 25, 2024, https://ieefa.org/articles/ieefa-tidal-wave-new-lng-supply-flood-market-amid-demand-uncertainty.

84 Eric Yep, “LNG market upheavals push Asian buyers to seek more legal protection in contracts,” S&P Global Commodity Insights, May 5, 2021, https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-research/latest-news/natural-gas/050521-lng-market-upheavals-push-asian-buyers-to-seek-more-legal-protection-in-contracts.