Egypt and Türkiye:

A Pragmatic Turn?

Issue Brief, May 2025

Key Takeaways

Egyptian-Turkish Enmity is Not Inevitable: After a decade of hostility, both Cairo and Ankara have concluded that cooperation and managing differences serves their respective national interests more effectively than adopting a zero-sum approach.

Intertwined Foreign and Domestic Politics: Domestic socio-economic challenges and changes in regional dynamics, from Libya to the Gulf, have all contributed to the thaw in Turkish-Egyptian relations.

Growing Trade Ties Strengthen Relations: Despite the diplomatic rupture, Egyptian-Turkish trade has steadily grown, further strengthening relations.

Normalization Can Help Egypt and Türkiye Manage their Disputes: Cairo and Ankara still have overlapping and sometimes competing interests in Libya, the Eastern Mediterranean, Sudan and elsewhere. Pragmatic diplomacy can help manage them.

Introduction

In February 2024, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan visited Egypt for the first time since 2012, effectively ending more than a decade of political and diplomatic rupture between Egypt and Türkiye.1 In September, President Abdel Fattah El Sisi reciprocated the visit, and both leaders also met at other regional and international gatherings throughout the year. These encounters were a culmination of several rounds of reconciliatory diplomatic efforts demonstrating that neither enmities nor friendships are set in stone.

This string of meetings, which started with a handshake on the sidelines of the 2022 FIFA World Cup opening ceremony in Qatar, highlighted Ankara and Cairo’s realizations that cooperation, rather than conflict, is likely to serve their respective national interests. This is particularly critical at a challenging economic, political, and security juncture for the region. Numerous bilateral Egyptian-Turkish meetings throughout 2024 resulted in 17 Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) aimed at increasing trade to over $15 billion a year (from $10 billion), coordination on regional issues, the selling of Turkish drones to Egypt, and the launch of a joint High-Level Strategic Cooperation Council.2

This issue brief argues that the normalization of relations between Egypt and Türkiye is a direct outcome of two interconnected variables: shifting regional dynamics and the domestic socio-economic challenges facing each country. These shifts are arguably exacerbated by a host of issues including Libya’s political and military fragmentation, intra-Gulf reconciliation, Israel’s wars on Gaza and Lebanon, and the economic fallout from both the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

While the normalization of relations is an important step after a decade of animosity, it does not imply that Egypt and Türkiye have reached agreement on all their differences. Nevertheless, it pushes Cairo and Ankara to use pragmatism and both bilateral and multi-track diplomacy to manage their differences and search for points of convergence. This is particularly important at a time of rapid regional and international changes and growing overlaps between Turkish and Egyptian interests.

The Seeds of the Conflict

Ankara and Cairo’s diplomatic rift started with Türkiye’s protests against then-defense minister Sisi’s overthrow of late Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi in 2013.3 While Türkiye saw the move as a coup, Egypt’s officials and media hailed it a necessary step, with strong public support. Türkiye subsequently provided refuge for exiled Egyptian opposition figures, specifically members of the Muslim Brotherhood, and allowed them access to media platforms.

The ensuing tug-of-war resulted from the countries’ divergent positions and ideological approaches on a wide range of issues, including the wars in Libya and Syria, political Islam, the demarcation of maritime boundaries in the eastern Mediterranean, and the blockade on Qatar by the Arab Quartet. In each of these cases, Cairo and Ankara backed opposing sides, or used their leverage to weaken the other’s position. Nonetheless, it is important to highlight that bilateral economic and trade ties, while initially weakened, were maintained, and the 2005 Free Trade Agreement remained in place.4

Despite an initial stagnation, the volume of trade has been steadily growing in recent years. According to Egypt’s Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), bilateral trade increased by 14 percent from 2021 to 2022, reaching $7.7 billion from $6.7 billion.5 The 2022-2023 report from the Central Bank of Egypt showed that Türkiye was Egypt’s fifth-largest trading partner, ahead of countries like Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom, while Egypt was Türkiye’s largest trading partner in Africa.6 In 2024, the Turkish Foreign Economic Relations Board (DEİK) estimated that 200 Turkish companies operate in Egypt, with $3 billion in investments, and directly or indirectly providing over 170,000 jobs.7

Shifting Geopolitics, a Decade On

Many factors have impacted the bilateral relationship between Egypt and Türkiye over the past decade. The 10 years that elapsed between rupture and reconciliation were marred by political posturing and scathing media attacks, reaching a climax in 2019-2020 with the civil war in Libya8 and the founding of the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), which excluded Türkiye.9

In 2019, when Benghazi-based General Khalifa Haftar’s forces launched an attempt to seize Tripoli, the operation unleashed a series of unintended consequences.10 The failed operation placed Egypt and Türkiye on a path towards direct military confrontation. Türkiye’s support for the forces of the Tripoli-based, and United Nations-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) proved decisive in reversing the advance of Haftar’s forces.11 This prompted Egypt (along with the United Arab Emirates and Russia), to threaten direct intervention in the event of pro-Türkiye forces attacking Sirte.12 Shifting power dynamics, an entrenched Turkish presence, and a military stalemate in Libya eventually came to constitute a geopolitical motivation for both Egypt and Türkiye to consider reconciliation.

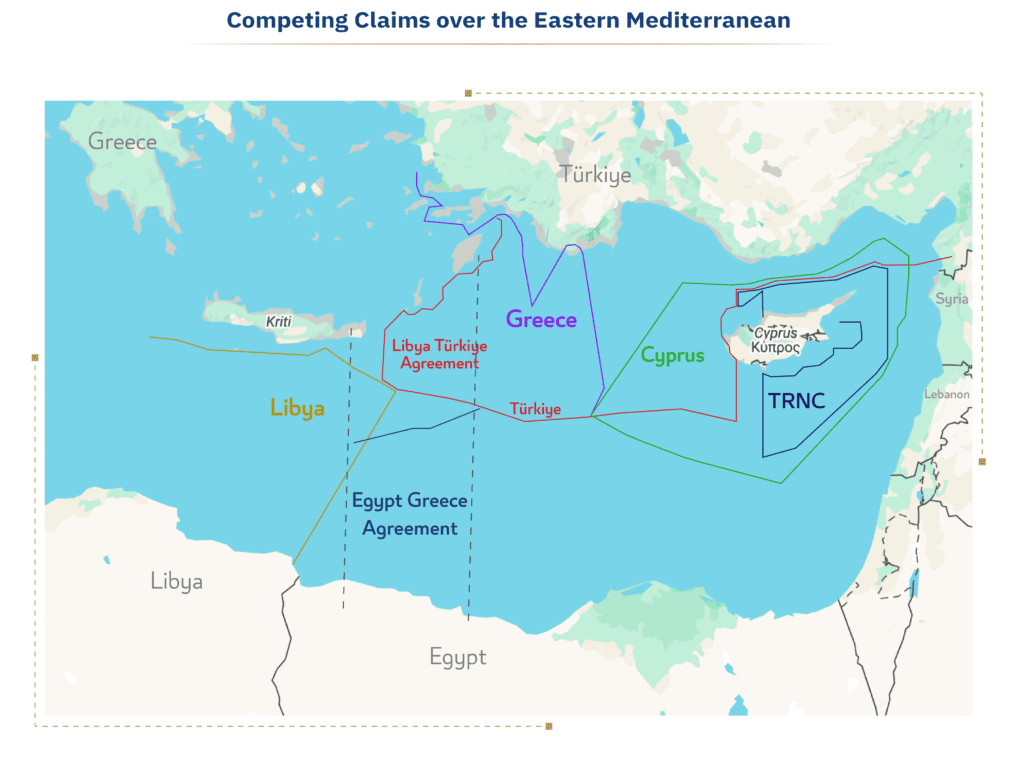

In addition to its military backing, Türkiye signed a maritime deal with the Tripoli government, creating an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) between their respective shores and allowing for Turkish undersea hydrocarbonexploration.13 The deal worsened already tense relations between Türkiye, on the one hand, and Greece and Cyprus on the other, complicating longstanding disputes on maritime boundaries in the Mediterranean.14 It also disrupted the plans of the EMGF, which brought Egypt, Greece and Cyprus, among others, together to develop and coordinate the exploration of natural gas in territorial waters—but had excluded Türkiye.

These disputes developed in a context of relatively tight coordination between Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE on various regional issues, including the 2017 blockade of Qatar. This watershed moment in Arab and Middle Eastern politics was reminiscent of the Arab Cold War of the 1950s and 1960s. The blockade was a chance for Türkiye to assert its role in the region, and to balance against the Saudi-Emirati-Egyptian bloc by supporting Qatar and boosting bilateral economic and military relations. The Arab quartet eventually dropped their demands and reconciled with Qatar in January 2021. By then, Qatar had considerably strengthened its ties with both Iran and Türkiye.

Qatar’s reintegration into the region, which coincided with the election of Joe Biden as then President of the United States, gradually de-escalated tensions, allowing for normalization among various regional players.15 This recalibration also took place in the aftermath of other critical events in the region such as attacks by the Houthis in Yemen on Saudi and Emirati territory, the Abraham Accords, and other socio-economic challenges.

The regional thaw in relations ushered in a diplomatic and transactional approach, between Türkiye and Egypt, that prioritized stability as well as increasing trade and investment opportunities. This dynamic was evident when Erdoğan visited both the UAE and Saudi Arabia in 2022. The relatively positive atmosphere at the time, helped start a process of mending regional ties including between Saudi Arabia and Iran,16 rehabilitating Bashar al-Assad’s regime,17 and eventually nurturing reconciliation between Egypt and Türkiye.

Sources: Turkey’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Anadolu Agency; Greek Media Reports; Flanders Marine Institute.18

Note: Some Exclusive Economic Zones are disputed.

Domestic Challenges

The shifting regional dynamics that prompted Turkish-Egyptian reconciliation should not be seen in isolation from their respective domestic political and socio-economic challenges. Domestic socio-economic stability contributes to states’ capacities to project power beyond their borders, while instability creates the opposite effect. This will be critical for both Egypt and Türkiye in the coming years, with growing uncertainties over political transitions; at the time of writing, both Sisi and Erdoğan are in their final terms, according to their countries’ constitutions.19

While bilateral economic and trade ties remained intact in the face of the political rift, both Egypt and Türkiye experienced critical upheavals in their domestic socio-economic situation in recent years.20 Some of these problems are due to internal factors, namely structural economic and fiscal challenges and mismanagement. These issues left Ankara and Cairo exposed to economic shocks, such as the sluggish post-pandemic recovery, frictions with the Gulf states, the consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the fallout from Israel’s war on Gaza. These uncertainties and regional instabilities have slowed and, in some cases, discouraged foreign direct investment (FDI). The knock-on effects, particularly on energy and food prices, exacerbated the difficulties caused by currency devaluations and subdued FDI in terms of higher inflation, raised interest rates, and debt.21 For instance, Egypt’s inflation hit a record high of 40% in 2023, while Türkiye’s hit a 24 year high in 2022 at 85.5%.22

Expanding economic ties is therefore a priority for both governments and is reflected by growing bilateral trade. Building a diversified, integrated system of economic and trade exchanges offers higher developmental potential as opposed to transactional exchanges of capital and labor alone, which is often the case for regional states with large populations but limited resources and those with smaller populations and greater wealth. Therefore, trade agreements remain resilient in the face of political rifts due to the considerable cost disruptions that they could inflict on investors, consumers, and the overall national economy.23 In addition, ruling regimes have an interest in minimizing socio-economic tensions that could lead to domestic strife, a critical issue for both Egypt and Türkiye.

Prospects for Collaboration and Contestation

Emerging pragmatism in Egypt-Türkiye ties is a crucial step forward. Its sustainability, however, is tied to their respective willingness to manage differences directly and diplomatically. So far, both countries appear keen on strengthening bilateral economic and trade ties and expanding coordination as their interests continue to converge with regional shifts and the impact of disruptive U.S. policies under President Donald Trump.

However, this does not mean that the Turkish-Egyptian rivalry will cease to exist. In the foreseeable future, several of the original points of contention will likely remain unresolved—namely, diverging interests in Libya, maritime border disputes, and Türkiye’s exclusion from the EMGF. Furthermore, other areas might exacerbate tensions, particularly evolving dynamics in Syria, Sudan, and the Horn of Africa. It is important to note that the centrality of Libya and Sudan to Egypt’s national security and regional standing are equivalent to the significance of developments in Iraq and Syria to Türkiye. The primary difference is that while Türkiye has established itself as a key player in Libya and, to a lesser extent, in Sudan, Egypt does not have equivalent leverage in Syria and Iraq.

Competition in Libya

Since 2020, the fault lines in Libya have largely cemented in the form of an east-west divide. In response, Egypt and Türkiye have each demonstrated openness to developing ties with groups they formerly opposed. However, this will not change Egypt’s opposition to the Turkish military presence nor Ankara’s security influence on the Tripoli government. Libya’s hydrocarbon resources, infrastructure projects, and economic opportunities are attractive to both Egypt and Türkiye and will likely serve as the primary incentive for preserving Libya’s security and stability in the near term. However, this focus could come at the expense of any immediate plans for unifying fragmented civilian and security institutions or engaging in a serious political process.

The other key foreign actors in Libya are the UAE and Russia, both of which continue to carve out spheres of influence that overlap and compete with those of Egypt and Türkiye. Since 2021, Abu Dhabi has gradually reduced its interventions and instead attempted to balance between its support to Haftar and reconciliation with Abdul Hamid Dbeibah’s government in Tripoli.24 This has included participation in mediation efforts to resume oil exports,25 defusing tensions after the appointment of a new National Oil Company chief in 2022,26 withdrawing support for mercenaries, and looking to benefit from Libya’s strategic location.27 Russia, on the other hand, is reviving its presence and role in Libya by using territories (particularly in the East, under Haftar) as a base for its Africa operations.28 The December 2024 fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria was a blow to Russia, but within days, it had reportedly transferred military equipment and resources to Libya from Syria, Belarus, and Russia itself.29

It is unlikely that these Russian transfers are temporary, and while they do not directly upset the fragile stalemate in Libya in the immediate term, they could prove a destabilizing factor in the future. Moreover, the increased Russian military presence is not only a threat to Libya, but also to Türkiye and Egypt—as well as to Europe, especially when the Ukraine war comes to end.30 As the sands in Libya shift and a multiplicity of foreign actors and armed groups vie to protect their economic gains and political power, there remains room for local actors to upend the fragile stability imposed by external forces.

Maritime Borders and the EMGF

Bilateral reconciliation and the return of relative stability in Libya could help Egypt and Türkiye unlock cooperation in hydrocarbon exploration, easing some of the tensions around maritime demarcation and EEZs. While Egypt and Türkiye diverge on how maritime borders are defined and the interpretation of the Law of the Sea, the main maritime border disputes pit Türkiye against Greece and Cyprus. When it signed a maritime demarcation agreement with Greece in 2020, Egypt took into consideration Türkiye’s disputes with Greece and Cyprus, and attempted to balance among the three countries, despite Ankara’s positions.31

Türkiye is unlikely to join the EMGF, despite its rapprochement with Egypt and outreach to Greece, as this would require accepting maritime boundaries it has long contested, as well as addressing the complex question of Cyprus.32 A potential maritime demarcation with the new Syrian authorities will also likely further complicate the picture.33 This deal could potentially intensify power play in the Mediterranean by connecting Türkiye’s interests in both Libya and Syria.34

A Seismic Shift in Syria

The toppling of the Assad regime by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) was politically unpalatable for the Egyptian regime, which continues to view political Islam as a threat. Over the past two years, Egypt supported the rehabilitation of the Assad regime, despite the latter’s long record of atrocities. Nonetheless, after waiting two weeks, Egypt’s foreign minister spoke with his newly appointed Syrian counterpart.35 President Sisi issued a statement congratulating HTS leader Ahmed al-Sharaa on his appointment as Syria’s president,36 and they held a bilateral meeting at the emergency Arab League summit in Cairo in early March 2025.37 Despite these moves, Egypt is far from fully embracing the new Syrian leadership, and is unlikely to publicly offer mediation assistance or support for reconstruction efforts. However, it will keep official communication channels open, while maintaining a “wait and see” approach.

Türkiye’s position is in stark contrast to that of Egypt. Türkiye spent more than a decade supporting efforts to remove Assad’s regime, intervening militarily to weaken it and aiding a number of opposition forces even as it struggled with the socioeconomic burden of hosting millions of Syrian refugees.38 Hence, Assad’s downfall represents a significant opportunity for Türkiye to reshape the political, economic, and security situation in Syria, particularly in light of a weaker Russia and Iran.39 Notably, Türkiye’s Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan was the first high-level foreign dignitary to meet Syria’s new leaders in Damascus.40 However, despite its rush to embrace, rehabilitate, influence, and trade with the new Syria, Türkiye’s efforts to expand its political and economic engagement with Syria is already beset by obstacles, including sanctions, domestic Syrian frictions, and competing regional visions. Furthermore, simmering tensions between Israel and Türkiye over Syria will undoubtedly influence any developments on the ground.41

Sudan and the Horn of Africa

Egypt and Türkiye both share interests in Sudan and the Horn of Africa that could benefit from the thaw in relations. Both sides support a stable Sudan to advance their overlapping, but sometimes diverging, political and economic interests. While Egypt prioritized security, Türkiye used investments as its entry point to develop relations with Sudan.42 Since the eruption of the civil war in 2023, both Egypt and Türkiye (among others) have attempted to facilitate a diplomatic solution, so far to no avail. Both countries eventually backed43 the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) against the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), perhaps spurred by reports of involvement by Iran, Russia, and the UAE,44 states whose interests in Sudan compete with those of Egypt and Türkiye.45

The picture is more complicated in the Horn of Africa, particularly in relation to Ethiopia and Somalia. Egypt has tense relations with Ethiopia, given years of unsuccessful negotiations over Nile water rights and the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Ethiopia tends to view any Egyptian move in the region as a threat, as is evident in press coverage and statements after successive Egyptian-Somali meetings46and the trilateral summit between the presidents of Egypt, Eritrea, and Somalia in 2024.47

Türkiye, on the other hand, has been developing economic and security relations with Ethiopia for over a decade.48 This is part of a broader Turkish strategy to expand its presence and engagements to other countries in the Horn of Africa, including Somalia, which now hosts a Turkish military base49 and has signed several major deals with Ankara.50 The changing dynamics and competing interests in the region were reflected in the January 2024 announcement of an MOU between Ethiopia and Somaliland, offering the former access to a Red Sea port in exchange for recognition of the latter’s independence.51

The news reverberated across the region, prompting Egypt and Somalia’s government to build closer ties, and triggering a scramble to defuse tensions between Mogadishu and Addis Ababa. Türkiye’s relations with both sides helped in this regard.52 Yet the de-escalation would not last long were the Trump administration to recognize Somaliland’s independence. This would allow Ethiopia to proceed with its plans to access the Red Sea, further complicating its relationship with Egypt—and others.

Conclusion

The relationship between Egypt and Türkiye has made a critical shift, from a zero-sum mentality to a pragmatic approach focused on managing differences. The normalization of bilateral ties, illustrated by high-level diplomatic exchanges and substantial economic agreements, reflects a mutual recognition of the benefits of cooperation in a highly volatile region. This is demonstrated by the steady growth of bilateral trade, underscoring that economic interdependence can serve as a powerful catalyst for political rapprochement.

However, this newfound cooperation does not erase the underlying complexities and potential for renewed rivalry. The enduring fault lines in Libya, Syria, Sudan, and the Horn of Africa, as well as the contested maritime boundaries in the Eastern Mediterranean, highlight the persistent obstacles to long-term stability in relations between the two countries.

Looking ahead, the success of this rapprochement hinges on Egypt and Türkiye’s ability to maintain open channels of communication and prioritize diplomatic solutions. The signing of numerous MOUs and the establishment of the High-Level Strategic Cooperation Council provide a framework for continued engagement, but the long-term stability of their relationship will depend on their willingness to address contentious issues in a spirit of compromise.

Moreover, the ability of Egypt and Türkiye to forge a constructive partnership will not only shape their bilateral relations but will also have significant implications for the broader Middle East and North Africa, a region that continues to grapple with instability. Ultimately, while the past decade has been marked by discord, the current trajectory gives reasons for cautious optimism, provided that both countries remain committed to a path of pragmatic engagement and mutual respect.