COVID-19

and Trust in Government:

Can Countries Come Out Ahead?

Issue Brief, June 2022

Key Takeaways

It is possible for countries that performed well to reap benefits in terms of increased citizen trust in government

The number of countries falling into this category is relatively small, amounting to less than 10 percent of the total. The size of this increase may vary from 3-4 percentage points to as high as 30 points.

The majority of countries experienced a relatively brief “rally around the flag” effect

There was an initial surge in public confidence followed by a subsequent erosion in trust, often to levels below where it stood at the initial outbreak. High levels of political polarization can dampen this surge.

It is not clear that governments and politicians who performed poorly against the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequently lost public trust will pay a significant political price

A handful may eventually face the public’s wrath. Yet trust is a complex metric, and few voters are likely to view COVID-19 as the definitive lens through which the credibility and performance of their political leaders should be evaluated.

Introduction

The topic of trust in government runs to the core of a state’s perceived credibility and legitimacy. When the public trusts its government, citizens are more likely to follow its guidance and directives, whether that involves paying taxes, obeying traffic laws, or getting vaccinated and wearing masks. When trust is absent, neglect and evasion are more prevalent, and the challenge of addressing collective action problems increases. When compliance can be a matter of life and death, as during a global pandemic, dysfunctional outcomes resulting from a lack of trust can be serious or even tragic. A variety of surveys and epidemiological studies have underscored the importance of confidence in government as a critical factor in encouraging public behaviors that can ultimately contain pandemics such as COVID-19.1

Government Performance and Trust

While the linkage between trust and public behavior has been well-established, there is a less well understood side of the trust equation. Can governments who perform well in combating the COVID-19 pandemic expect to receive a boost in public confidence? Will those who perform poorly witness declines in public trust? And is the electorate or the broader political system likely to reward or punish leaders based on how they respond to the pandemic? This issue brief reviews survey data and analysis from nearly 50 countries in an effort to shed light on these questions.

Before diving into the comparative evidence, a few caveats are in order. Trust itself is an imperfectly understood concept whose drivers have yet to be fully captured and quantified. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has flagged five components of trust in public institutions, including responsiveness, reliability, integrity, openness, and fairness.2 Beyond these normative principles, trust also has an empirical or utilitarian dimension. Governments (and by extension their leaders, policies, and associated institutions) are expected to produce results, advance important social goals, and respond effectively to collective problems. Public expectations also come into play, and trust can be shaped not just by what a government is doing today or how well it has performed in the past, but by perceptions of how it will perform in the future. The relative weight of these different factors may vary across polities or vary over time within a given polity, interacting in ways that are complex and producing results that may appear counter-intuitive.

Efforts to measure trust must often grapple with a host of complex conceptual and methodological issues. A variety of discrete concepts—trustworthiness, integrity, confidence, competency and expertise—may all be rolled into a single survey question about “trust.” Understandings of trust and a willingness to trust others may vary across cultures, as well as confidence that opinions may be voiced freely without threat of retaliation. Responses to survey questions may not reflect actual individual behavior.3

Aside from the United States and a handful of OECD countries, longitudinal data on trust is relatively rare, although there has been a significant expansion in comparative analyses since the 1990s. Prior to the pandemic, global surveys revealed a gradual erosion of public trust in government over the past decade and a half in the United States and Latin America, whereas trust in European governments remained relatively flat and trust in Asian governments had trended up.4

With regard to COVID-19, it is difficult to definitively attribute movements in public trust to government performance during the pandemic. A few detailed surveys exist that specifically address public perceptions of government responses to the pandemic, but many standardized longitudinal assessments of government trust do not disaggregate by key drivers. Methodological differences between surveys often prohibit direct comparisons between them, and the virus follows its own path independent of when surveys are scheduled and conducted.

Another complicating factor is that trust is not equally distributed across society but tends to vary by subgroups. On balance, older and healthier individuals have tended to trust government more during the pandemic; women tend to trust more than men; and those who voted for the party in power have tended to have higher levels of trust than those who did not. Paradoxically, both the more educated and the less well-off tend to trust government less than the general public.5

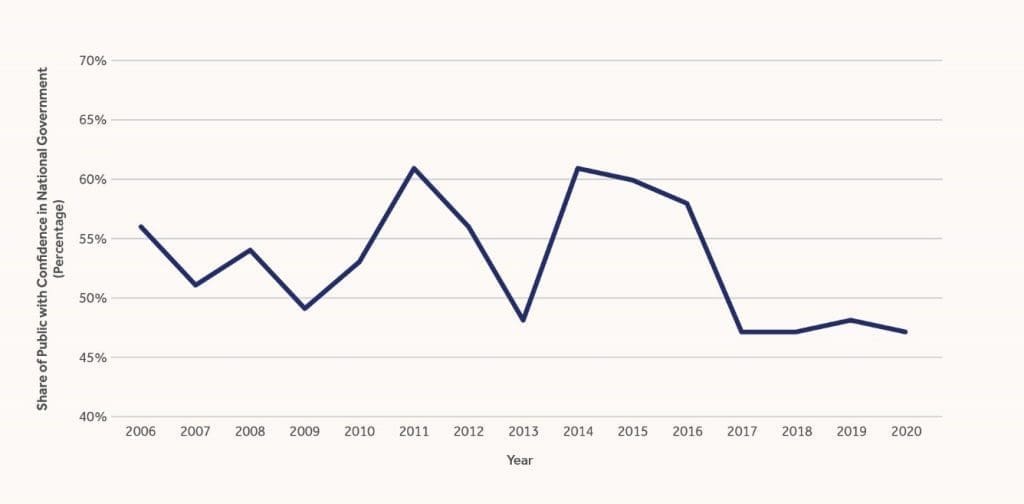

The choice of benchmarks is important, as trust varies both across government entities as well as over time. In Tunisia, for example, 96 percent of the public had a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in the military in January 2020; 76 percent felt the same about the police; 27 percent towards the public administration; and only 11 percent had confidence in parliament—a pattern that is often repeated in other countries.6 As figure 1 below indicates, in Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries where the Gallup organization has been engaged in polling, there has been a general decline in confidence in government over the last decade. Aggregate trust peaked during the heady expectations of the Arab Spring and surged again during the period from 2014 to 2016, largely in response to political developments in Egypt. But it has subsequently fallen off consistently, reaching its nadir just prior to the outbreak of the pandemic. Data from the Arab Barometer paints a comparable picture. Jordan, for example, witnessed a decline from 72 percent of the public trusting government to a greater or medium extent in 2010-11 to 38 percent in 2018-19. Tunisia witnessed a drop from 62 percent to 20 percent, and the region as a whole witnessed an average decline from 53 percent to 34 percent.7

Figure 1: Confidence in National Government in the MENA Region8

While trust in government often evolves relatively slowly over time, there are moments when it can shift rapidly. Trust in information provided by the American Centers for Disease Control (CDC) stood at 84 percent at the outbreak of the pandemic, whereas 14 percent of the public had limited or no trust. As of January 2022, these numbers stood at 62 percent and 38 percent, respectively.9 Some analyses have underscored the importance of the media in shaping attitudes towards the veracity of public health data being provided by government, noting that it can easily create an environment of skepticism and mistrust.10 In the United States, a survey of New Hampshire residents in July 2020 found that only 3 percent of those who listened frequently to conservative talk radio believed that government’s highest priority should be containing the virus, as opposed to 76 percent of the general public.11 On the upside, media coverage can also significantly improve the public’s willingness to take on board public health messages. Polling data from the United States in August 2021, for example, noted a decline in vaccine hesitancy among Fox News watchers from 37 percent to 27 percent after leading network personalities endorsed the vaccines.12

COVID-19 Performance and the Comparative Evidence to Date

Survey data indicates that strong performance in limiting the mortality and morbidity from the COVID-19 virus can be associated with significant increases in trust. By most metrics, Australia and New Zealand have performed relatively well against the pandemic, and there is evidence that trust in government increased substantially among their citizens. According to the Edelman Trust Barometer (ETB), Australia witnessed a 17 percent improvement in trust in government between 2020 and 2021.13 (As will be noted below, more detailed analyses have put this increase even higher.) In a separate survey conducted in July 2020, a total of 78 percent of New Zealand and 72 percent of Australian respondents agreed that their country’s management of the COVID-19 pandemic had increased their trust in government. Large majorities also stated that confidence in their public health system had improved, a sign that this rising tide was lifting several boats.14

A handful of others who performed well against the virus have enjoyed a “trust dividend” of sorts. Within the European Union (EU), while a limited number of countries have enjoyed relatively high levels of trust throughout, Denmark appears to be the only country where trust in government actually increased during the latter stages of the pandemic.15 Among MENA countries, Morocco proactively addressed the pandemic through a combination of lockdowns and social distancing measures, economic relief (albeit more limited than many OECD countries) and an impressive vaccination drive.16 As figure 2 indicates, it is also one of the few countries currently enjoying higher levels of trust in government than prior to the pandemic.

Figure 2: Trust in National Government Compared to COVID-19 Daily New Cases in Morocco17

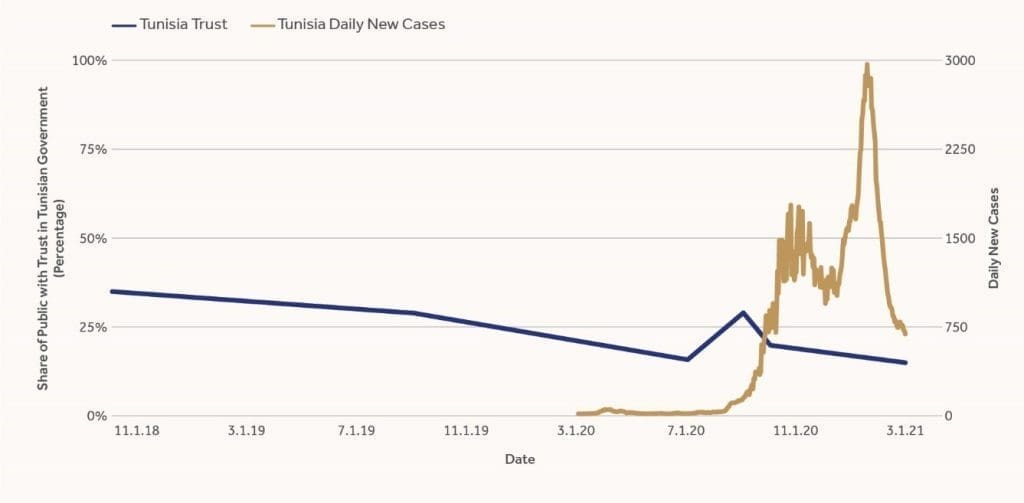

Figure 3 presents an interesting study in contrasts between Morocco and nearby Tunisia. Tunisia performed quite well against the virus during the early months and witnessed a modest increase in trust in government, but it quickly dissipated as morbidity numbers increased.

Figure 3: Trust in National Government Compared to COVID-19 Daily New Cases in Tunisia18

Tunisia’s trajectory is not unusual. British public opinion underwent a significant surge during the early phase of the outbreak, with trust in government increasing by around 14 percentage points between December 2019 and May 2020. This surge was followed by a gradual decline in trust over time to pre-pandemic levels.19 South Korea, who by most metrics performed well against the virus, witnessed a similar surge in trust in government between January and May 2020, followed by an even greater decline.20 Other countries, including China, Mexico, Canada, Spain, and Germany, experienced similar although less pronounced arcs.

Brazil and India have the second and third highest cumulative death rates from COVID-19 globally, trailing only the United States, and both Jair Bolsonaro and Narendra Modi have come under harsh criticism for their approach to the pandemic. Bolsonaro has downplayed the virus, calling it “a little flu,” and has refused to be vaccinated.21 He has resisted lockdown measures at the state level, pushed unproven drugs such as hydroxychloroquine, failed to ensure that hospitals had adequate protective equipment or oxygen supplies, and turned down or refused to purchase vaccines on numerous occasions. In India, Modi has come under fire for the un-prepared status of Indian hospitals during the surge in 2021; his support for vaccine exports while many in the country remain unvaccinated; and his decision to allow large religious festivals to proceed and to conduct election rallies during a time of rising infections.

While neither government has performed well and both countries have suffered horribly from the virus, the political fate of these two leaders may ultimately be very different. Modi’s overall approval ratings have fallen from over 80 percent in October 2019 to just over 60 percent in April 2021, prompting one pollster to note that the prime minister “is facing the biggest political challenge of his career.”22 Yet he started from high rankings both in terms of his personal popularity as well as levels of overall public trust in his government. He remains the country’s most popular politician and is not scheduled to face the Indian electorate again until 2024. Overall trust in government is much lower in Brazil. Bolsonaro’s approval ratings are currently under water and sinking, with only 22 percent of Brazilians viewing him as doing a “good or excellent” job as opposed to 53 percent who disapprove of his performance.23 He will face a formidable rival in former President Luiz Lula da Silva in October 2022, against whom he is currently trailing in the polls by more than 20 points.24

Away from these extremes, Austria’s experience may serve as a more reliable guide. Its performance against COVID-19 has placed it in the company of countries, such as Germany and Switzerland, with significantly lower rates of mortality and morbidity than its neighbors to the south or east. Its economy entered the pandemic with strong macroeconomic indicators, suffered a sharp decline in spite of robust government support efforts, and is recovering at what the International Monetary Fund (IMF) describes as “a somewhat slower pace” than many other EU economies.25 Early in the pandemic, the government experienced a significant surge in public confidence across the political spectrum. Yet, trust dissipated quickly between March and July 2020, with the heaviest losses accruing in public perceptions of the federal government, parliament, and the media. (Austrian health authorities managed to escape this drop relatively unscathed.)26

Eventually, Austria witnessed one of the largest overall declines in government trust in Europe.27 The roots of this decline are complex and cannot be wholly attributed to the government’s response to COVID-19, but the latter has indeed made a contribution. By February 2021, 43 percent of Austrians felt that the government’s COVID-19 measures were appropriate, whereas 27 percent believed that they were excessive, and another 24 percent felt they were “sloppy”.28 In September 2021, the Menschen-Freiheit-Grundrechte party (“People, Freedom, Rights,” or MFG)—a newly created political grouping of COVID-19 vaccine skeptics and deniers—won seats in the Upper Austria regional government in Linz. Few observers view MFG as a dominant political player. It received only 6 percent of the vote in a conservative region of Austria, and the fall of Sebastian Kurz’s government in October 2021 was rooted in allegations of corruption, and not its COVID-19 performance. Yet, the speed of MFG’s rise was alarming, and in January 2022 it helped mobilize thousands on the streets of Vienna to protest vaccine mandates. MFG has made the task of governing Austria more fractious and has clearly complicated the country’s public health response to the Omicron variant.29

A Complex Legacy

Both the pandemic and public perceptions are continuing to evolve, and it would be premature to offer definitive conclusions at this stage. Yet several preliminary findings emerge from this overview of comparative global experience during the first two years that are likely to stand the test of time.

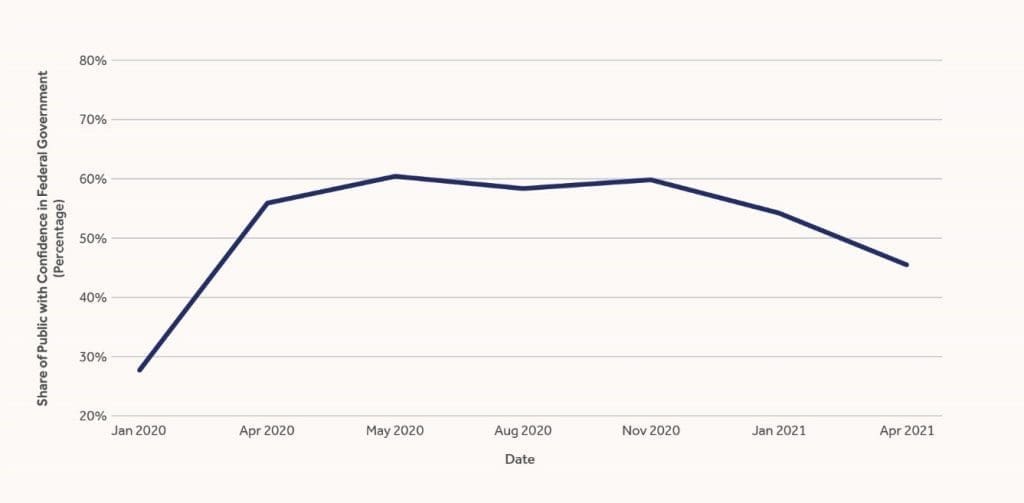

The first is that it is possible for countries that performed well against the pandemic to reap benefits in terms of increased citizen trust in government. The number of countries falling into this category globally is relatively small, amounting to less than 10 percent of the total. The size of this increase may vary. In countries where public trust was already high, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), it is typically relatively modest, on the order of 3-4 percentage points. In countries where levels of trust were lower, the bump could be more substantial. As figure 4 below indicates, Australia was able to enjoy a significant increase in public confidence in the federal government by nearly 30 points, in large part rebounding against what was perceived to be the government’s relatively poor performance during the bush fires of the previous summer.

Figure 4: Percent of Australians who had a Great Deal or Quite a Lot of Confidence in the Federal Government30

Second, the Australian experience also illustrates a much more common phenomenon. For many countries, the surge in government confidence during the pandemic has been temporary. They have subsequently witnessed an erosion in public trust, often to levels below where it was at the initial outbreak. This trajectory is consistent with observed public opinion trends during foreign policy crises, where one typically sees a sharp increase in favorable views of the government as part of an initial “rally around the flag” effect, which then falls off in subsequent months.31 The Edelman Trust Barometer exemplifies this trend. Four months into the pandemic, it noted that governments had become the most trusted societal institution, witnessing an average 11 percent increase since January 2020 across its survey countries. By January 2021, trust in both business and NGOs had topped trust in government, which had dropped by an aggregate of 8 percentage points in the intervening months.32 It appears likely that high levels of political polarization can dampen this surge in public opinion, which did not emerge in countries such as the United States and France.33

Third, it is less clear that governments and political leaders who performed poorly against the COVID-19 virus and experienced diminished public confidence will pay a significant political price. A handful, such as Bolsonaro, may ultimately face the public’s wrath. Yet trust is a complex metric as noted above, and few voters are likely to view COVID-19 as the definitive lens through which government legitimacy, credibility and performance should be evaluated. In some cases, such as Lebanon, the pandemic has played a secondary role against the broader backdrop of an economic meltdown and protracted political crisis. In others, political partisanship and affiliation may ultimately trump the pandemic in the minds of many voters. The next elections may take place far enough into the future that COVID-19 and its dislocations recede in the public’s consciousness. And pandemic responses will always be subject to the sturm und drang of the broader political process, where they are traded off against other objectives or mitigated by the demands of coalition politics.

COVID-19’s impact on the global political landscape will continue to be felt for quite some time in more nuanced ways, such as those involving the credibility and receptivity of certain groups to scientific data and expert recommendations; the growth in anti-elite sentiment; and the need to address economic inequality which has worsened during the pandemic. Political actors mobilized by the crisis, such as Austria’s MFG party, will continue to be active, most likely at the margins but still influencing the public health debate in their countries and exerting pressure on more mainstream parties to be responsive to their concerns.

There are a few measures that governments can take to bolster trust. The experience of Australia and New Zealand has underscored the importance of transparency and sustained communication grounded in evidence-based analysis. At the outset of the crisis, the Australian prime minister and state premiers gave daily press briefings accompanied by their respective chief medical officers.34 New Zealand invested heavily in communications and hired a leading advertising firm to help with its public outreach program. Its messaging focused on the type of concrete behaviors citizens would need to pursue to combat the virus, along with a more general request for empathy, compassion, and solidarity.35 Consistency has also been an important dimension of the messaging. Frequent changes in guidance from public health authorities, or a drop-off in communication once a particular wave of the virus passes, are less effective than careful, sustained messaging over time. Finding multiple avenues for delivering messages, including through personal physicians, media personalities and faith leaders is also important. And as recent experience in the United Kingdom underscores, it is important that political leaders “walk the talk” and take their own guidance seriously.36

For most governments, the credibility gained and then lost during the COVID-19 pandemic may (or may not) be re-established downstream in the wake of another crisis. In some, public health institutions have received an enduring bump-up in public confidence. Others, such as the American CDC, have lost credibility, at least among certain segments of the population. But for now—unless you are one of the fortunate denizens of Canberra, Casablanca, or Copenhagen—any “trust dividend” that governments could expect to reap from effectively combating the COVID-19 virus has in all likelihood already come and gone.