Sino-GCC

Relations:

Past, Present, and Future Trajectories

Issue Brief, June 2022

Key Takeaways1

China and the challenge of balancing between Saudi Arabia and Iran

In its approach to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), China has had to balance between regional rivals—Saudi Arabia and Iran. As regional tensions rise, it will be increasingly challenging for China to maintain that balance.

China does not want to play a bigger security role but may have to

Despite playing a larger role, China has no appetite to take over from the United States as the region’s security provider. Given its over-reliance on energy from the Gulf and its global ambitions, China may need to play a larger security role in the Gulf over the coming decades.

The GCC’s Own Balancing Act

Closer ties with China have raised concerns in the United States, so GCC states need to maintain their own delicate balancing between the United States and China.

In unity there is strength

To achieve the best outcomes in their engagement with China, GCC states should have a collective approach towards China. This will be increasingly difficult to achieve given the weakness of the Council’s collective foreign policy approach and disunity amongst member states.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and China have worked to build up their economic, political, and security relations. In 2020, China replaced the European Union as the GCC’s largest trading partner with bilateral trade valued at USD 161.4 billion.2 Massive infrastructure projects in the region, such as Qatar’s Lusail Stadium and high-speed rail lines in Saudi Arabia, provide lucrative opportunities for Chinese companies.3 The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is China’s largest export market and the largest non-oil trading partner in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region,4 and the country has also been a hub for Chinese COVID-19 vaccine production.5 China is also the largest customer of Omani crude oil, importing approximately 78.4 percent of its output, a substantial increase from 17.8 percent in 2002.6 Oman is slated to play a significant role in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).7

Increasing levels of engagement, while disturbing policymakers in the United States,8 demonstrate that both sides are seeking to deepen their ties over the coming decades. The visit in January 2022 by the head of the GCC and several GCC ministers to China has been described as “unprecedented.”9 The joint statement released following the meeting was ambitious, calling for the establishment of a strategic partnership, promotion of free trade agreement negotiations, and implementation of a free trade area.10 As GCC states and China deepen their engagement, they will have to navigate a complex set of regional and international factors that may constrain closer ties.

Historical Context: China’s Balancing between Saudi Arabia and Iran

The GCC’s earlier relationship with China can be viewed in the context of Sino-Iranian relations, established in 1971 during the Shah’s era. At the time, GCC states viewed these ties with suspicion, which only increased after the removal of the Shah and the flourishing of the relationship under the Islamic Republic. After GCC states established their own diplomatic relations with China during the 1980s, they continued to be suspicious of its intentions in Iran, especially since the two states were growing closer in several fields, including arms technology and energy.11 While publicly holding a neutral position, China had in fact provided covert support to the Islamic Republic during its conflict with Iraq (1980–1988).12

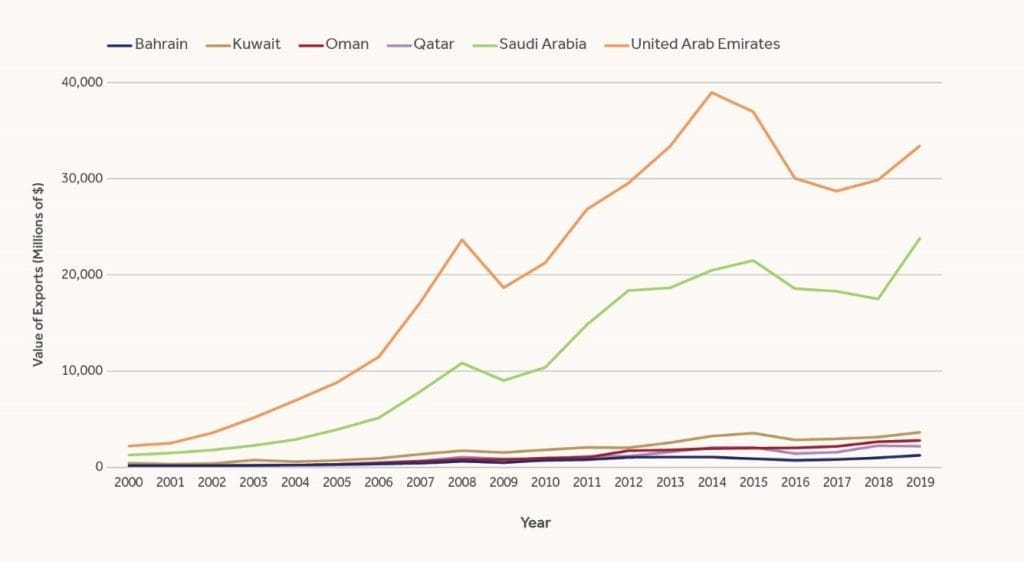

Despite these concerns, the GCC stance toward China has shifted considerably over the years. As one ex-GCC official commented, “The Chinese relationship with the Islamic Republic 30 years ago was seen as a major shift and threat to us. But the GCC saw a requirement to engage, which is our historical norm.”13 In 1993, a visit to the Gulf countries by Li Lanqing, China’s deputy premier, marked the beginning of China’s efforts toward energy cooperation with GCC countries,14 and thus energy security became a critical factor in GCC-China relations. In addition, China wanted to expand and diversify to new markets for its labor-intensive products, and so ever since the 1990s the UAE has become a more critical location for China’s manufactured products to be re-exported to countries in the MENA region (figure 1).15

Figure 1: China’s Exports to the GCC, 2000-2019

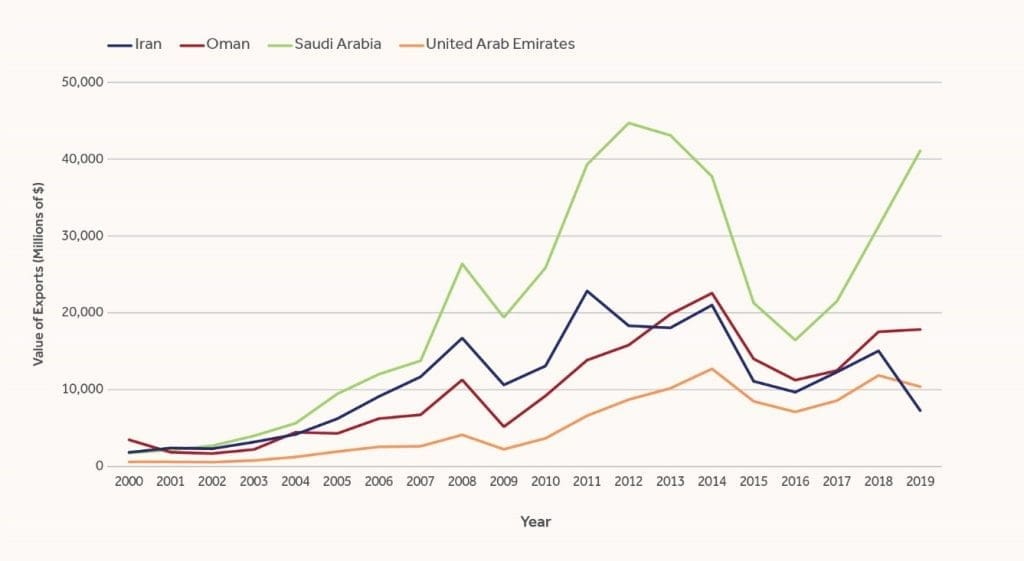

By the 2000s, the GCC’s economic engagement with China had arguably brought some balance to Beijing’s Iran policy,16 and since 2001 both Saudi Arabia and Iran have become the twin pillars of China’s approach to the Gulf,17 with both set to play a role in the BRI. China is the world’s largest importer of crude oil, and imports from the key exporters and Iran are critical for its economy (figure 2).

Figure 2: China’s Fuel Imports from Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman, and Iran, 2000–2019

While China has avoided entanglements in regional disputes and conflicts, the growing Saudi-Iranian rivalry over the past two decades has made it increasingly difficult for Chinese policymakers to balance China’s relationship with both regional powers. In addition to establishing a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with Saudi Arabia,18 China has also pursued a strategic partnership with Iran, which expands its economic footprint in several sectors across the country, including finance, agriculture, telecommunications, ports, and railways. In exchange, China is reportedly set to receive heavily discounted Iranian oil over the next twenty-five years.19 The agreement was first proposed by President Xi Xinping during a state visit to Iran in 2016 after the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was signed but was on hold during the Trump presidency after he withdrew from the nuclear agreement and adopted the “maximum pressure” policy on Iran. Xi’s proposal was finally signed in 2021 after Joe Biden’s election and in the final months of the Rouhani presidency.

The agreement, which has entered its implementation stages under President Raisi, has raised concerns in Saudi Arabia that its security interests are not being considered given that Iranian-backed proxies such as the Houthis continue to attack the kingdom. China has sought to alleviate this concern with Foreign Minister Wang Yi, stating that China “understands and supports the legitimate concerns of Saudi Arabia in safeguarding its national security.”20 China has also backed the new JCPOA negotiations and wants the nuclear accords reinstated. However, any deal that does not address Iran’s destabilizing regional activities may engulf China in a conflict between two of its key strategic allies in the Gulf.

Pandemic Diplomacy and Beyond

COVID-19 presented China with an opportunity to increase its influence and its outreach to MENA governments and their citizens. As public health systems came under pressure in the United States and European countries in 2020, China had reacted to the pandemic quickly and was able to begin sending medical supplies to countries across the world. GCC countries initially sent supplies to China, but as the crisis dragged on, they became recipients. According to one analyst, China’s pandemic diplomacy won over Gulf states who were grappling with the economic and medical fallout from the pandemic.21

Overall, China’s pandemic diplomacy should be viewed within the broader context as another soft-power tool to further entrench its presence in countries where it seeks diplomatic and economic influence and to supplant its Western rivals. It also underscores its efforts to cast itself as a global leader in health care. To reboot the impression that it was the source of the virus, through its vaccine and health care diplomacy efforts China wants to be seen as a responsible global leader that is capable of fighting the virus domestically and globally.

Building on its success at increasing its soft power during the pandemic, China sought to deepen its relations as the world slowly recovers. In early 2021, Wang Yi traveled to six Middle Eastern countries, including Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Oman.22 The visit can be viewed in the context of China’s objectives in the region as it adjusted to the Biden administration. Following from the tense exchange between the U.S. and Chinese delegations in Alaska in early 2021,23 and the Biden administration’s efforts to strengthen alliances with democracies around the world and forge a China strategy that combines engagement with containment, it is unsurprising that China is seeking to cement its relationships and alliances around the world, including in the Gulf. Yi’s visit to Saudi Arabia was not only important for both countries’ energy and trade partnerships; it also highlights the Saudi political cover and support of China’s approach to Xinjiang. Chinese media reported that during this meeting, Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman said: “Saudi Arabia firmly supports China’s legitimate position on affairs related to Xinjiang and Hong Kong, opposes interference in China’s internal affairs under any pretext, and rejects the attempt by certain parties to sow dissent between China and the Islamic world.”24

Yi’s stop in the UAE underscores the importance of deeper ties between Abu Dhabi and Beijing. As a regional trade hub and major oil exporter to the Asian market, the UAE has prioritized its relationship and deepened its engagement with China earlier than other GCC states. The UAE’s strategy of controlling access to key maritime chokepoints in the Indian Ocean, the Horn of Africa, and the Red Sea made Abu Dhabi an indispensable partner for Beijing.25 The ties are focused not only on trade and energy, but now also on global health and vaccine diplomacy, with the UAE becoming a hub of production for the Sinopharm vaccine.26

The GCC’s Balancing between China and the United States

Historically, balancing between the United States and China was not a critical issue for GCC states. However, the growing U.S.- China rivalry and China’s expanding global footprint has increasingly compelled them to do so. Navigating this change is particularly delicate for GCC states given their reliance on U.S. security commitments. The perception of U.S. withdrawal from the region has prompted GCC states, working on their own and less within the framework of the GCC, to diversify their security partnerships and sources of armaments. But can China replace the United States as a security partner in the region?

The short answer is no. Indeed, while China has been touted as a potential security partner, its primary interests in the MENA region continue to be expanding its commercial reach and locking in energy supplies, all while avoiding any security entanglements. Some prominent Chinese commentators, such as Wang Jisi, have periodically advocated a foreign policy more focused on security concerns in the Middle East and Western Asia,26 but this view is in the minority in a Chinese state that may be interested in somewhat more security coordination in the Middle East yet has little desire to play the kind of intense militarized goal that the United States does.

China does maintain a small base in Djibouti, with 400–1,000 troops providing logistical support for antipiracy operations in the Gulf of Aden and humanitarian programs in Africa.28 However, the base is largely focused on China’s relations with sub-Saharan Africa rather than the MENA region. China has also periodically contributed forces to peacekeeping efforts in the region.29

China has sought to play a security role through the export of defense technology. A 2019 report about Saudi Arabia cooperating with China to develop missiles, for example, provoked considerable debate in the United States, even though Saudi Arabia sources only a tiny portion of its overall arms purchases from China. In the past, Saudi Arabia has turned to China for access to ballistic missile technology only when the United States was unwilling to provide it.30

The U.S. Congress has warned Saudi Arabia against weapons purchases from Russia or China, while the U.S. administration under President Donald Trump used this point to argue for extensive U.S. arms sales to the kingdom.31 In 2022, these reports were confirmed by U.S. satellite imagery showing that Saudi Arabia has built a facility and is already manufacturing ballistic missiles with the help of China. This development has raised concerns in Washington that the Saudi ballistic missile program could alter the regional power dynamics and complicate efforts to renegotiate the JCPOA.32

The UAE’s relationship with China has also alarmed Washington, which had wanted the UAE to exclude the information technology firm Huawei from its 5G network and limit its defense cooperation with the country, fearing that China will use its relationship with the UAE to obtain sensitive technologies, including that in the F35 fighter, which the UAE was slated to acquire. The U.S. Congress even introduced the “Monitoring China-UAE Cooperation Act.”33 The UAE in response decided to freeze the F35 deal and instead purchased a French-made Rafale fighter jet to signal to the United States that it will not be pressured on its ties with China, and that it has other options when it comes to defense procurement.

These challenges in Saudi-U.S. and UAE-U.S. relations highlight a dynamic that works to China’s advantage in the Gulf. While both UAE’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed and Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman enjoyed a close relationship with the Trump administration, this clearly did not continue under Biden. In contrast, China, with its authoritarian model, enjoys continuity of leadership and policies, even when presidents change. China has been able to present itself as a long-time dependable partner unperturbed by the instability of a revolving door of governments in the United States and Europe.

Having said that, the United States continues to be the key security underwriter in the region. Despite its withdrawal from Afghanistan, the United States still maintains a sizable military presence in the region. In Qatar, it maintains the Udeid Air Base, which was expanded in 202134 and played a critical role in the withdrawal from Afghanistan. Manama continues to be the base of the U.S. Fifth Fleet and U.S. Naval Forces Central Command (CENTCOM).35 In the UAE, the United States has a presence at the Al Dharfa Air Base, where its personnel fired Patriot missiles to defend the UAE from Houthi attacks in 2022.36 There is no realistic scenario in which China can step in and fill these gaps should the United States withdraw completely from the GCC.

Future Trajectories and Policy Challenges

The successful implementation of BRI projects in the MENA region, specifically in the Gulf, will entail closer political engagement—which China has long avoided—because these investments highlight some of the contradictions in China’s approach to the region.37 As argued, it will prove increasingly difficult for China to both develop closer relations with Saudi Arabia and maintain its strategic and economic relations with Iran.38

Regardless, there is considerable demand for Chinese capital in the region, as various GCC monarchies seek to implement “vision” plans of big-push economic development and diversification.39 China’s authoritarian model of economic development no doubt also holds appeal to MENA rulers, who are averse to making any democratic concessions. This model of authoritarian development finds resonance in the Gulf, which showcased itself as a bastion of stability during the Arab uprisings in 2010-2011.

As GCC policymakers seek to deepen their relationships with China, incremental and well-defined engagement will be key. The U.S.-China rivalry will likely shape the twenty-first century, and although the rivalry will play out primarily in Asia, it is likely to have effects across the MENA region.40 Just as Chinese policymakers will have to carefully balance their relationship between Saudi Arabia and Iran, GCC policymakers will have to do a balancing of their own between China and the United States.

The United States has long been the primary external actor in MENA security and is likely to continue to be in the immediate future. Saudi Arabia, like other GCC states, relies on security guarantees from the United States. Their inability to develop comprehensive self-defense capabilities has made U.S. security assurances vital. In addition to its military presence in GCC countries, the United States conducts exercises in partnership with all six GCC states, provides combined training for their militaries, and assists in making purchased U.S. hardware more interoperable.41 To that end, U.S. security guarantees will always be more important to the GCC than stronger economic relations with China, unless Chinese policymakers decide to become a part of the security architecture of the region. Overall, GCC policymakers will be well served to deepen their engagement with China in a coordinated fashion. The ability to speak with one unified GCC voice will likely produce more positive outcomes for political, economic, and security engagement with China.