Can Multipolar Blocs Offer Iran a Way Out of Isolation?

Issue Brief, December 2025

Key Takeaways

Using Multipolarity to Counter Western Dominance: Iran aims to capitalize on its engagement with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and BRICS to legitimize its role in a multipolar order and reduce its vulnerability to the West.

Sanctions Have Reinvigorated Tehran’s “Look East” Agenda: The institution of snapback sanctions has hardened Tehran’s pivot to the East and the Global South, making integration into multilateral bodies central to its survival strategy.

BRICS and SCO Offer Symbolic Gains and Cooperation: The blocs offer partial economic relief, symbolic legitimacy, modest trade, and limited technological cooperation, as well as giving Tehran a platform on the international stage.

Multilateral Organizations Cannot Effectively Address Iran’s Economic Isolation: Despite these benefits, SCO and BRICS member states will continue to carefully manage their relationships with the United States and Iran. This tension will limit either organizations’ capacity to help Tehran bypass sanctions or deliver a strategic transformation.

Introduction

Iran is facing intensifying pressures on the international stage. In June of 2025, Israel and the United States launched a military assault on the Islamic Republic’s nuclear program, even as talks on the program were underway between Tehran and Washington. Just two months later, the three European signatories to the 2015 nuclear deal triggered the agreement’s snapback mechanism, reimposing international sanctions on Iran. The E3 (France, Germany, and the United Kingdom) argued that Iran had failed to show goodwill, meet its commitments under the deal, or return to nuclear talks.1

Tehran condemned the move, warning that it would respond appropriately, but leaving open channels for diplomacy.2 Despite these efforts, in September 2025, the UN Security Council triggered the snapback mechanism, reintroducing far-reaching sanctions on an already struggling Iranian economy.

For Iran, the E3’s decision was evidence that Western powers will not come to an equitable agreement that considers Tehran’s right to a national nuclear program. Viewed from Tehran, this underlined the need for Iran to diversify its international engagements in order to withstand sanctions by enhancing its self-sufficiency, expanding regional trade, and pursuing alternative alliances. This has placed the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the BRICS bloc at the center of Iran’s diversification strategy.

Following repeated, unsuccessful attempts in previous years, Tehran joined the SCO in 2023. In recent years, the SCO’s agenda has evolved from initially focusing on addressing border disputes and cross-border terrorism among initial members China, Russia, and the former Soviet Central Asian republics, to cover economic integration, infrastructure development, and scientific cooperation. Its membership has also expanded to include India, Pakistan, and now Iran.

BRICS, originally a loose association of emerging economies, welcomed Iran to its ranks as part of its enlargement drive in 2024–2025. The bloc presents itself as a platform for multipolar governance, financial de-dollarization, and South-South cooperation–an agenda that resonates with Tehran. Iran’s leadership portrays participation in these organizations as part of a strategy aimed at breaking away from a U.S.-dominated international order, realigning with countries in the Global South, particularly by deepening ties with Russia and China, and promoting a multipolar world order.

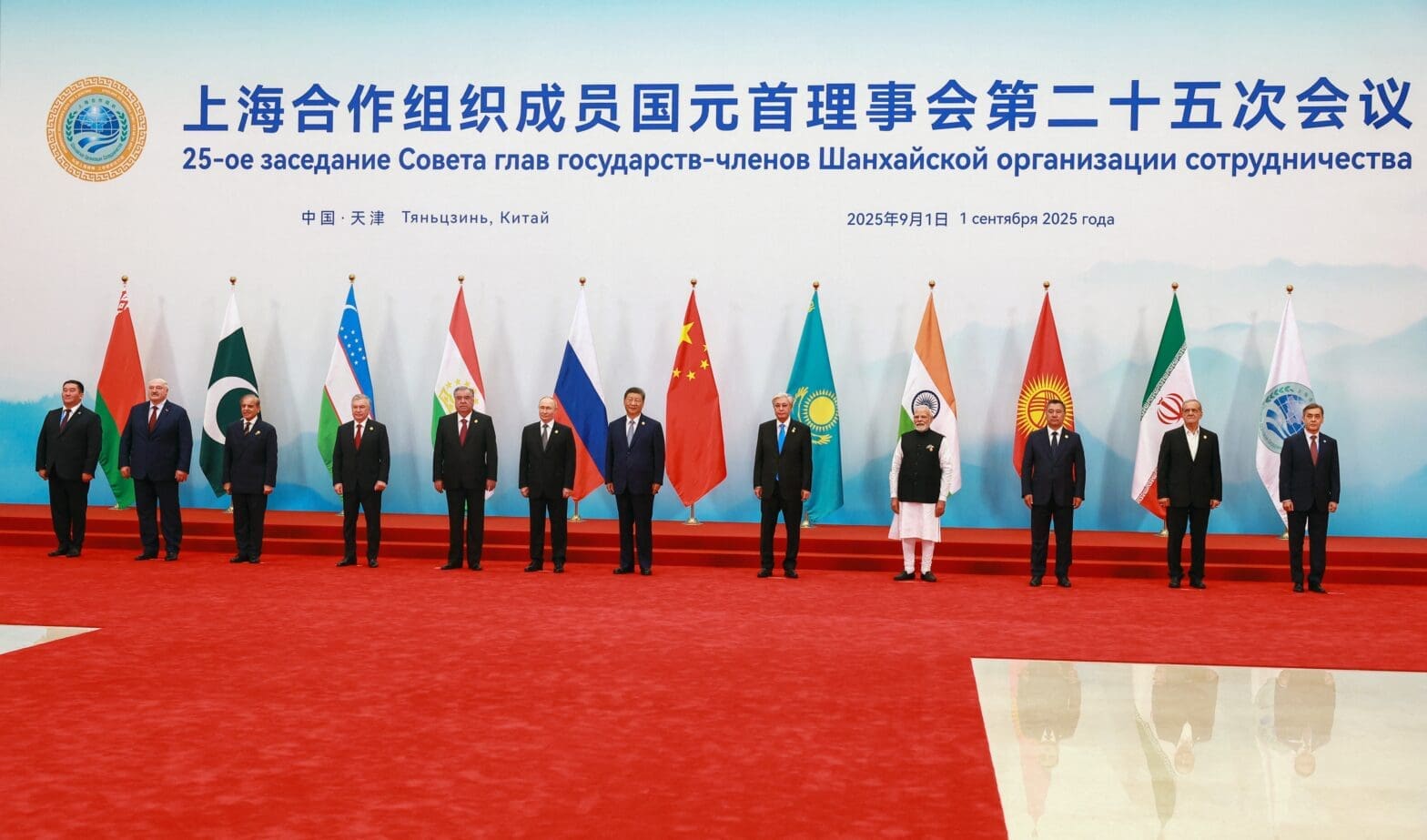

The “Look East” (negah be sharq) agenda, initially adopted under former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, reflected this drive. While the policy appeared to lose urgency during nuclear negotiations and the early years of the 2015 nuclear deal (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or JCPOA), it regained its significance as the deal faltered following the U.S. withdrawal during President Donald Trump’s first term in 2018. Under Ebrahim Raisi’s presidency (2021-2024), the Look East policy became the “ultimate alternative, and not a complement, to Iran’s relations with the West.”3 President Masoud Pezeshkian remains aligned with this posture, viewing SCO and BRICS as key buffers against a Western dominated global order. Addressing the SCO Council of Heads of State in September 2025, he reiterated Iran’s commitment to SCO, referring to it as a “pillar of multipolarization.”4

However, key questions remain over the tangible benefits of these alternative multilateral initiatives. In the immediate future, the urgent question for Iran is the extent to which these multilateral institutions can cushion the impact of sanctions. This issue brief examines Iran’s relationship with the SCO and BRICS, and evaluates the viability of Iran gaining economic and political leverage from these bodies.

The issue brief argues that Iran faces serious limitations in advancing its objectives through SCO and BRICS. It seems unlikely that Tehran can leverage these blocs to address the immediate crisis over the reinstitution of sanctions. While friendly towards Iran, China and Russia have carefully managed their engagement with Iran, vis a vis these bodies, to avoid a confrontation with the United States. As a result, it is unlikely that Iran will receive meaningful strategic support from SCO or BRICS in the face of heightened international tensions and UN sanctions. Iran’s membership in these organizations thus offers political and symbolic advantages, but limited functional value.

Iran’s Economic Woes

Iran’s economy has experienced sharp fluctuations driven by international sanctions, volatile oil export volumes, and internal structural challenges. After a brief period of recovery following the signing of the JCPOA, the economy was hit by the U.S. withdrawal from the agreement in 2018 and the reimposition of U.S. sanctions. These measures disrupted oil exports, weakened the rial, and contributed to persistent inflation.

Export income from oil, Iran’s main source of foreign currency, has been under stress due to sanctions. Iran has found ways of bypassing U.S. sanctions in recent years, through, for instance, shipping oil in vessels flying third countries’ flags to sell to China at discounted prices.5 While this has maintained a limited flow of exports, it has resulted in a significant cut in Iran’s revenues.6 Since the beginning of his second term, President Trump reinforced primary and secondary sanctions on Iran, meaning Chinese companies dealing with the Islamic Republic have also been subject to U.S. sanctions, resulting in a sharp decline in oil exports and revenues.

This challenging trade environment has constrained economic growth. Based on the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) data, Iran’s economy contracted, following the re-imposition of U.S. sanctions in 2018, only partially recovering in 2022 through the use of sanction-evasion mechanisms. These measures typically involve document falsification to conceal the point of origin of oil exports, mid-sea tanker-to-tanker transfers, bypassing conventional shipping lanes, turning off transponders, and working with front companies specifically set up to funnel funds to Iran.7 In October 2025, the U.S. State Department placed secondary sanctions on 40 individuals, companies, and vessels for allegedly helping Iran export oil.8 It is almost certain that snapback sanctions will further undermine the prospects of Iran’s economic recovery.

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF).9

The slowdown in economic growth has fueled inflation, which has become a pressing issue for Iranians. According to the IMF, Iran’s annual inflation has consistently increased since 2018, peaking above 40% in some years.10 In March 2025, inflation was at 37.1%, translating to prices rising by 3.3% every month.11 decimating Iranian consumers’ purchasing power. Identifying mechanisms to bypass UN-imposed sanctions and isolation is therefore urgent for Tehran.

The Promise of Multilateral Blocs

In light of these pressures, Iran’s pursuit of deeper integration within the SCO and BRICS is motivated both by an attempt to increase strategic distance from the West and a quest to bolster its “resistance economy” model. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei views the resistance economy model as one of fostering self-reliance and is particularly aimed at reducing Iran’s dependence on the West. The model emphasizes domestic production, waste reduction, and economic and trade diversification.12 Throughout decades of sanctions, isolation, and pressure over its regional policy and nuclear program, Tehran has sought counter-balancing partnerships to offset U.S. pressure. Iran therefore views SCO and the BRICS as avenues that can potentially offer strategic advantages, economic dividends, and diplomatic cover.

Iran seeks to leverage membership in these organizations to resist Western pressure and to challenge or circumnavigate international sanctions. In 2023, upon Iran’s accession to SCO, late President Ebrahim Raisi declared that Iran’s entry allowed it to “resist… Western unilateralism and create regional and international integrity.”13 This rhetoric has been typical of Tehran’s broader diplomatic logic of aligning with powers such as China, Russia, and India.

SCO membership is expected to elevate Iran’s integration in Eurasian security and economic frameworks, signaling that, despite U.S. efforts to isolate it, Iran retains a presence on a regional scale. Similarly, BRICS membership underscores Tehran’s desire for integration into the Global South to contest Western hegemony. Snapback sanctions, particularly those targeting oil exports and the financial sector, have again underlined the imperative for Tehran to diversify its trade partners. SCO membership is expected to facilitate access to Chinese and Russian trade corridors, including the Belt and Road Initiative, as well as to Central Asian markets.

Iran’s First Vice President Mohammad Mokhber even proposed “a comprehensive transit [route] to link all the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) member states through Iran.”14 In that ambitious outlook, trade and transportation via Iran would connect “South/Southeast Asia, Central Asia, the Caucasus, Russia, the Black Sea and Europe.”15 BRICS presents an even larger opportunity: its members account for approximately 40% of the global population and over 30% of global GDP.16 BRICS discussions on alternative payment systems and local currencies resonate with Iran’s de-dollarization strategy. The Iranian leadership appears to have pinned its hopes on the capacity of BRICS to bolster Iran’s economy in the face of snapback sanctions.17

Iran also views its engagement with BRICS as a boost for long-term energy (a key Iranian export) contracts with India, China, and Brazil. Javad Oji, Iran’s former Minister of Petroleum, was part of the Iranian delegation that attended the 2023 BRICS Summit alongside President Raisi, indicating the link Iran between its BRICS membership and prospects for expanding market access for its energy exports.18 In 2024, Iran’s President Masoud Pezeshkian attended the BRICS summit in Moscow, describing his participation as an opportunity to put an end to “U.S. unilateralism.” 19 He emphasized that “BRICS member states could achieve fruitful cooperation in the fields of agriculture, energy, industry, trade, and tourism.”20

Iran has pursued the same aspirations in its relations with the SCO. For example, Iranian authorities showed enthusiasm about the idea of establishing an SCO Energy Club, an idea first presented by Russian President Vladimir Putin nearly two decades ago.21 Tehran sees the Energy Club serving as another prospective platform to advocate for new energy pipelines and grid projects, positioning itself as a regional bridge, integral to SCO’s success. However, the proposed club has not moved beyond the conception phase, merely serving as an occasional SCO side forum for discussions on energy priorities.22 This is symptomatic of the limits of SCO summits.

Research and innovation are another area of interest; in the context of international restrictions, Iran is keen on fostering research exchange with SCO member states as an avenue to bypass sanctions. Ongoing university exchanges and collaborations are portrayed as evidence of the West’s inability to embargo knowledge and a reflection of scientific resilience. In this vein, joint projects with Russia and China are viewed by Tehran as a byproduct of its BRICS membership, pinning significant hopes on their capacity to deliver technological advances for Iran.

Iran perceives its SCO and BRICS membership as a sign of political legitimacy, and as evidence that Iran is not isolated, but rather welcomed into influential international organizations. Tehran seeks to reassure itself that its reorientation towards the Global South will bring the economic and political rewards which it has been unable to secure by attempting to rebuild relations with the West. This framing aims to reassure domestic audiences and amplify resistance narratives.

Yet despite these efforts, Iran’s ambitions for multipolar diplomacy and economic diversification under its “resistance economy” model have faced significant limitations. Iran’s efforts are challenged both by continued U.S. pressure and by the gap between Iran’s aspirations and the international capacity of BRICS and the SCO.

Prospects and Limits

Iran’s entry into the SCO and BRICS was celebrated in Tehran as the culmination of years of diplomacy aimed at orienting Iran toward the East. For Tehran, accession itself is a political victory, bearing significant symbolic value. Yet questions persist over the tangible benefits of these associations, particularly in terms of mitigating the impact of sanctions. The SCO has been criticized for lacking enforcement mechanisms, making it largely symbolic, rather than a cohesive security or economic organization. Furthermore, SCO is governed by consensus decision-making. As a result, it is paralyzed in the face of major regional challenges and disputes, such as those between member states India and Pakistan.23

For instance, it was the absence of consensus among SCO members that prevented Iran’s entry for almost a decade, dating back to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s presidency. At the time, Central Asian republics feared Iran’s SCO membership would drag them into a confrontation with the United States. Such fears have not eroded. As a bloc, the SCO remains risk-averse and reluctant to be embroiled in sensitive issues such as mitigating the impact of sanctions on Iran.

A similar dynamic affects BRICS. Its ambitious expansion has made BRICS a collection of diverse economies. This diversity presents a challenge for coordinated action, especially in relation to shielding Iran. De-dollarization, a key agenda item for BRICS, offers the best example of these divergent views.

China and Russia have long advocated for de-dollarization to challenge the U.S. dollar’s global dominance and alleviate international sanctions on Russia which aligns with Iran’s strategic priorities. At the 2025 BRICS summit, Tehran proposed the establishment of a joint bank among SCO member states as an important step toward de-dollarization.24

Other states view de-dollarization as aspirational and not an immediate policy. Brazil’s Central Bank, for instance, sees no “realistic prospect of emerging nations in the BRICS group creating markets large enough to topple the U.S. dollar’s dominance within the next 10 years.”25 Brazil, South Africa, and India support de-dollarization in principle as a way to enhance their financial autonomy, but not as a geopolitical tool to defy the West.26 Their priorities remain tied to their national economic growth. This clearly falls short of Iran’s expectations of BRICS as a shield against Western sanctions.

BRICS and SCO members’ willingness, or lack thereof, to engage Iran is primarily based on their respective national priorities in relation to the United States. U.S. primary sanctions restrict direct engagement between Iranian and U.S. entities, whereas secondary sanctions extend extraterritorially to penalize non-U.S. actors dealing with Iran. Most BRICS and SCO member states cannot afford to be isolated from Western financial markets by violating sanctions against Iran. Even Russia and China, despite their rhetoric, are cautious about exposing their major banks to U.S. penalties or engaging in a direct confrontation with Washington over Iran.

Similar dynamics apply to Iranian hopes for expanded export opportunities. China already absorbs large volumes of Iranian crude oil at discounted rates. India has intermittently signaled interest in resuming oil imports, although U.S. sanctions have been a key hurdle. While strategically independent, India balances its energy ties with Iran against its much larger partnership with the United States.27 Brazil and South Africa remain distant markets with limited infrastructure links. Moreover, the adoption of snapback sanctions makes sanction evasion even more difficult. Iran has therefore not been able to translate its memberships in either bloc into effective sanction-evasion mechanisms.

These tensions are further complicated by the BRICS including energy importers that are also direct competitors with Iran. Since 2022, Russia has flooded Asian markets with discounted oil, often undercutting Iranian exports.28 Iran and Russia compete in the very markets where they advocate coordination. For instance, India replaced some of its Iranian crude oil imports with Russian oil following President Trump’s maximum pressure campaign against Iran in 2018.29

Other members have voiced frustration over the blocs’ shortcomings. Prior to the Summit of the Council of Heads of State of the SCO in 2024, Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev reportedly stated “over the past 20 years, it was not possible to implement a single major economic project under the auspices of the SCO.”30 As a result, Iran is finding it difficult to convert declarations and rhetoric into concrete policies and the investments needed to alleviate sanctions-related restrictions.

Iran has benefitted from bilateral arrangements such as barter trade with Russia or yuan-denominated sales to China. Yet these bilateral agreements were formed outside multilateral frameworks. While SCO and BRICS offer symbolic solidarity, they do not provide the institutional frameworks necessary for robust agreements nor do they offer the institutionalized relief that global institutions, such as the IMF or World Bank, can deliver.

Beyond economics, Iran views the SCO and BRICS as avenues for technological cooperation. This has been most evident in mid-level fields such as pharmaceuticals, renewable energy, and applied sciences. However, Iran’s access to advanced technology remains limited. Russia and China appear reluctant to transfer their most advanced systems, such as nano-technology, fearing proliferation or competition.31

That said, even limited partnerships carry symbolic weight, and can be leveraged for a domestic audience. Hardliners emphasize that these alignments prove Iran can survive without the West,32 an optimistic view that deliberately overlooks the structural limits of these multilateral organizations. Yet Iran’s engagement with the SCO and BRICS is likely to yield limited tangible benefits. Iran will gain diplomatic cover and limited trade opportunities, but they will be modest, given the backdrop of snapback sanctions. Even before the institution of the snapback mechanism, the SCO and BRICS struggled to shield Iran from the global reach of U.S. sanctions. Both organizations lack the financial depth, cohesion, and political will to absorb the risks involved in challenging the United States over Iran.

Conclusion

Iran’s embrace of the SCO and BRICS is tactical and strategic. In the short run, it hopes to leverage its membership in these institutions to keep its economy afloat. In the long run, it holds aspirations for these institutions to undermine the supremacy of the United States and add momentum to the rise of a multipolar world—a vision it shares with China and Russia.

The E3’s decision to trigger snapback sanctions has further reinforced Iran’s “Look East” agenda. Tehran now views SCO and BRICS as central to its survival, as sources of diplomatic support, trade opportunities, and protection from isolation. But such transformative relief is likely to remain unfulfilled. Structural constraints limit both organizations’ ability to deliver decisive relief for Iran.

BRICS and the SCO both suffer from weak institutional capacity and competing interests among member states. China and Russia, the principal powers within both blocs, have not indicated a willingness to support Iran with sanction-busting measures through these organizations, lest they become entangled in Iran-U.S. tensions. Moreover, internal rivalries hamper the SCO’s security agenda, while BRICS lacks financial cohesion. In their current forms, the anticipated benefits of de-dollarization and technology transfers from these groups will likely remain incremental at best.

SCO and BRICS can however amplify Iran’s global, and regional, standing and provide new avenues of cooperation. This serves an important political and diplomatic purpose. But neither organization is in a position to shield Iran from sanctions in a meaningful way—nor to reshape the global order in the near future.