After the Shock:

The Israel-Iran War’s Economic Impact on the Gulf

Policy Note, July 2025

Introduction

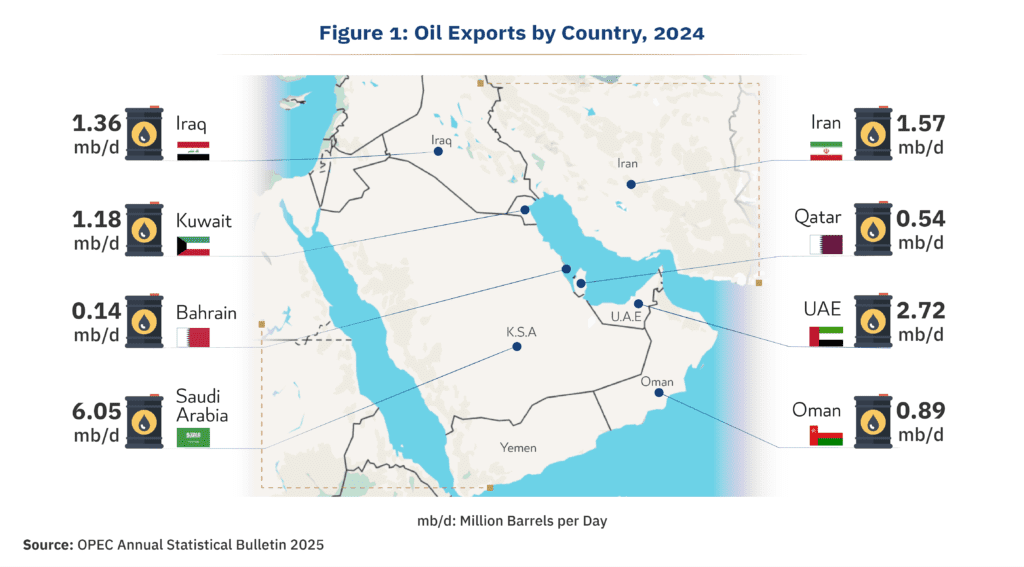

The aftermath of Israel’s June attack on Iran presents a complex picture for Gulf economies. Globally, the most pressing issue was the threat of a closure of the Strait of Hormuz, the bottleneck through which about 33 percent of global oil exports flowed in 2024 (Figure 1).1 Yet given the stakes, market reactions to the attack were moderate. Oil prices increased by 17 percent to $80 per barrel during the conflict, but fell back to pre-war levels immediately after the ceasefire (Figure 2).2 Even within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), markets appeared relatively relaxed about the war (Figure 3).3 Nor did maritime traffic through the Strait decline during the war (Figure 4).4 This muted anxiety was likely due to the expectation that most parties in the war would want to prevent a closure at all costs.

This muted reaction is at odds with the Strait’s overwhelming importance not only for GCC hydrocarbon exports but also for non-hydrocarbon shipping, which accounts for much of the rest of the Gulf economy. But the threat goes beyond the potential closure of a vital maritime chokepoint. Airspace closures and flight cancellations towards the end of the war, and—perhaps most importantly—the Iranian strike on Qatar’s Al Udeid air base have fundamentally shifted perspectives on the Gulf’s reputation as a tranquil, safe haven and global travel hub.

In light of this shock, Gulf countries need to recalibrate not only their geopolitical and security strategies, but also their economic policy. This must include a reassessment of global economic relations, regional economic cooperation, and economic self-sufficiency and resilience. In the short term, GCC states will need to overcome internal frictions and launch a concerted effort to dampen the blow of any potential kinetic attack on domestic industries, strategic stockpiles, and intra-GCC logistics.

Background

Various aspects of the Israel-Iran war need to be considered separately as they had different effects on the GCC. First, the specter of a blockade of the Strait of Hormuz conjured memories of the Iran-Iraq war 40 years ago. Back then, Iran threatened to close the Strait in retaliation against the U.S. and the Gulf states for siding with Iraq. While it never imposed a full blockade, Iran staged attacks on shipping to demonstrate its seriousness.5 This prompted the Gulf Arab states to build pipeline infrastructure to circumvent the Strait.6 Saudi Arabia built the East-West Crude Oil Pipeline (also known as the “Petroline”), with the capability to pump 5 million barrels per day (bpd) from its main oil fields in the Eastern Province to the Red Sea, while the United Arab Emirates built a pipeline from Abu Dhabi’s oil fields to Fujairah, on the far side of the Strait. More recently, several GCC–to–Mediterranean land corridor solutions have been initiated.7

Second, Israel’s surprise attack, which disrupted ongoing nuclear negotiations between Iran and the U.S., came on the heels of President Donald Trump’s visit to the Gulf in April. That visit was seen as a diplomatic victory for the GCC states.8 Trump had decided to make Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE the destinations of the first foreign trip of his second term, skipping Israel. The tour resulted in the signing of several Memoranda of Understanding for trillions-worth of GCC investments in the U.S. economy. The feeling in the Gulf was that concerted diplomatic and economic efforts would buy clout in U.S. policymaking circles. Yet Israel’s attack, backed—and later joined—by the U.S., shattered this impression barely two months later, reinforcing the notion of the U.S. as a less-than-reliable partner, and casting doubt on whether the Gulf can gain significant influence over the U.S. by means of normalization with Israel and promises of trillion-dollar investments.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the Iranian strike on Qatar’s Al Udeid base inflicted another shock of an altogether different quality. In contrast to the threat to the Strait of Hormuz, this was a direct attack on GCC soil, shattering the GCC states’ veneer of invulnerability to kinetic war. The fact that the U.S. removed all its troops from the base before the attack — leaving the responsibility for air defense to the Qatari military — and that this retaliation was (most likely) orchestrated between the U.S. and Iran over the heads of Qatar and the other Gulf states, further cemented the impression that U.S. bases may be more of a security liability than an asset.9 It also severely undermined the trust that had been built between the GCC and Iran over recent years.

Across the entire Gulf, the psychological shock has been profound. Reports about Egyptian hotels getting suddenly booked out by Gulf citizens hoping to wait out the conflict, along with viral smartphone videos of the missile attacks on Qatar, reminded GCC residents of Houthi missile and drone attacks on Saudi Arabia and the UAE in 2019—or for those old enough to remember it, Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait and Scud missile attacks on Saudi Arabia and Bahrain. The airspace closure echoed Covid-19 groundings, and Qataris remembered the traumatic 2017 blockade and near-invasion of their country. Gulf citizens, non-citizen residents and foreign investors—who had come to see the Gulf as an island in a sea of crises and conflicts—are now re-evaluating that impression.

Economic Consequences

A month after the war, the ceasefire appears to be holding, and markets are mostly back to normal. However, none of the underlying issues seem solved, or indeed, solvable.10 Israel is ramping up the extermination of Gaza while remaining bent on all-out war with Iran—a project that Prime Minister Netanyahu has loudly advocated for over 30 years.11 The U.S.-Iran nuclear talks have been derailed, the U.S. has shown itself to be an unreliable negotiating partner, and the war has given Iran ample motivation to double down on deterrence, possibly even nuclear. It is, therefore, hard to envision a peaceful resolution to the current impasse.

As such, while the war’s direct economic consequences on the Gulf were limited, the risk of renewed escalation is substantial. Financial markets have partially priced this in, for example, in increased insurance premiums for shipping through the Strait of Hormuz. But, as mentioned above, the Strait is far from the only problem. Even if the GCC countries were spared, the destabilization or destruction of Iran would not be in their political or economic interest. It is true that the containment of Iran has diminished its geopolitical and economic power. But, while a contained Iran may be desirable for the GCC, a destroyed Iran is not.12 Not only is Iran an important counterweight in the precarious regional balance of power, it is also an important economic partner. Notably, many of Iran’s imports pass through the GCC, especially the UAE, as do its exports; some experts allege that sanctions evasion is a key driver of this trade relationship. In other words, the specter of Iran becoming a new Libya, Syria, Iraq, Somalia, or Afghanistan is not in the GCC’s political or financial interest.

Finally, the strike on Al Udeid may turn out to be the most economically significant shock. Economics has much to do with expectations. Nothing pushes away investors and foreign talent more than the prospect of conflict and instability. While the probability of serious destruction of physical infrastructure in the Gulf countries was essentially zero before the strike, it has since risen significantly. If the conflict remains isolated, and the ceasefire can be made to hold, the Gulf’s reputation will recover. But a renewed, more devastating attack, say on GCC ports, refineries, or government installations, could damage that perception permanently.

Policy Solutions for the GCC’s Dilemma

The aftermath of the war presents a dilemma for Gulf policymakers who are intent on limiting its economic impact and that of any future escalation. On the one hand, governments must actively prepare to soften the economic blow of a potential all-out war. On the other, it is essential to minimize the perceived likelihood of such a confrontation.

Concerted Diplomacy for Peace – Against the Odds

Retaining both investor and worker confidence requires GCC countries to undertake a concerted peace offensive, harnessing the region’s entire global diplomatic network to achieve lasting resolution. This means including not only the U.S. and its Western allies alongside Iran, but potentially other global powers as well—such as the BRICS bloc. Regarding Iran, the main difficulty will be to rebuild trust after the missile attack on Al Udeid. Simultaneously, the U.S. needs to restore Iran’s confidence in negotiations and in the White House’s ability to keep Israel from attacking.

The Gulf states will need Iran to provide credible assurances that they will be off limits in a potential future war. But the GCC can only secure this assurance if all its members present a united diplomatic front. Still, obtaining such a guarantee in the short term remains doubtful. Neither normalization efforts with Israel nor the GCC’s charm offensive towards the U.S. have yielded the hoped-for dividends in terms of security, diplomacy, or the economy. Even an all-out, unified GCC diplomatic offensive is therefore unlikely to make significant inroads to peace.

Limited Scope for Protection against Economic Damage

In addition to minimizing the likelihood of a renewed kinetic war involving the GCC, maximum effort needs to be directed at protecting GCC economies in a worst case scenario. This can be done by developing independent, broadly-sourced domestic defense capabilities. Qatar’s air defenses proved capable of largely parrying the Iranian strike. However, Iran’s strikes on Israel, with hits on military bases, intelligence installations, the defense ministry, ports and refineries, and inflicting an estimated $3 billion in economic damage,13 have demonstrated its ability to pierce even the most intensely protected airspace. Even more troublingly, the Gulf would have to jockey with Israel, Ukraine, and Taiwan for the limited and increasingly insufficient supply of air defense batteries and interceptors from the U.S., while having to defend an area many times larger than any of those theatres. As a result, it seems likely that a future escalation will entail the destruction of some military or economic GCC infrastructure. A missile war in the Gulf would also severely impact both passenger and cargo air traffic, possibly with an effect similar to the Covid-19 groundings.

Further, there seems to be no good economic defense against a blockade of the Strait of Hormuz. Iran has various options for closing the Strait: mining it, launching naval attacks with surface ships and “midget” submarines loitering invisibly on the sea floor,14 using sea- and airborne drones, or firing ballistic and cruise missiles. Another attack that would be virtually impossible to prevent could be on submarine communications cables.15 Pipelines to circumvent the Strait have no spare capacity to replace tanker traffic and have also proven to be vulnerable to attack.16 Nor can these pipelines secure the non-oil portion of shipping through the Strait, which accounts for about 40% of the trading volume. Moreover, proposals for land corridors to the Mediterranean, such as the India-Middle East-Europe corridor, are laden with their own problems. Most importantly, they do not replace the seaborne hydrocarbon exports to, and cargo imports from, Asia, which is the GCC’s largest import and export partner by far.17 Finally, Iran still has the ability, through its Houthi allies, to impact the other regional chokepoint, the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, which not even U.S. and European military efforts have been able to secure.18 In short, the GCC has no convincing short- or medium-term solution to the problem of the Strait of Hormuz as an economic lifeline.

Need for GCC Defense Solidarity and Economic Cooperation

In terms of actionable, effective steps, there are two key lessons from the war. First, given the unreliability of non-Gulf partners outlined above, the bloc’s collective security should be based on internal collaboration between GCC member states.19 This will require major efforts and relationship-building. The GCC’s military cooperation wing, the “Peninsular Shield Force,” and the appetite for mutual defense assurances have a long way to go, with national interest often taking precedence over collective security, as exemplified by the Qatar blockade. However, the shock of the war, especially the Al Udeid attack, has jolted GCC leaders into action and solidarity. For example, UAE president Mohammed bin Zayed visited Doha on an impromptu visit after the attack, perhaps prompting a revival of a Gulf defense arrangement. Giving the recent GCC security vision teeth and the Peninsular Shield Force an air defense wing could be steps in that direction. At the same time, the impossibility to protect the Gulf from a disastrous Iranian attack (missile or blockade) means that a concerted GCC-Iran dialog must aim to repair the damaged relations.

Second, the war has demonstrated that the Gulf cannot ignore the possibility of another war, with potentially disastrous impacts on the domestic economy. This necessitates measures to increase regional economic resilience, including building up domestic industrial capacity in critical sectors such as food and defense, further diversifying the supply network for essential materials and components, expanding regional logistics infrastructure with appropriate redundancies in case of war, and building national stockpiles that can insulate the region against massive supply disruptions. Just-in-time supply management practices need to be re-evaluated to take into account the risk of disruption. In the long run, the only way to reduce economic exposure to a tanker blockade will be to accelerate the decoupling of the economy from hydrocarbon exports. Again, these measures would best be taken in the framework of regional collaboration—which will only be possible if the region overcomes persistent political and economic rivalries, especially between the two largest economies, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.20

Conclusion

The “12-day war” between Israel and Iran has had remarkably limited effects on global and regional markets. However, substantial risks remain for the GCC, as the underlying causes of the conflict remain unresolved (and in some cases have been exacerbated). The war, especially the strike on Al Udeid, has shown that the Gulf states are not immune to conflicts and crises in the broader MENA region. It has also deflated the GCC’s sense of growing diplomatic influence, both on Western “partners” and on Iran. Finally, it has highlighted the Gulf’s inexorable dependence on vulnerable chokepoints.

The key lesson from the war is the need for a renewed sense of collaboration within the GCC, especially on defense and the economy. One of the few beneficial outcomes of the war may be a renewed incentive to overcome intra-GCC disunity and rivalries in the face of external risks. The bloc’s members must coordinate economic measures to build regional resilience—such as domestic industrial capacities, strategic stockpiles, robust infrastructure and supply networks. Global diplomatic relations, with the U.S., Iran, BRICS members and others, need to be harmonized within the GCC to maximize leverage, while keeping in mind the lesson that overly trusting relations with any particular party would be misplaced.

In the long term, economic export orientation must be balanced with domestic production that reduces the economic risk emanating from the regional chokepoints, including an accelerated transition away from hydrocarbon exports and avoidance of overreliance on imports, particularly from China.