Bordering on Crisis:

The Future of Algeria-Mali Relations

Issue Brief, July 2025

Key Takeaways

Algeria and Mali are at Loggerheads: The downing of a drone, in March 2025, on the Algeria-Mali border has pushed a long-brewing diplomatic crisis to the brink. Bamako accuses Algiers of interfering in its internal politics, while Algiers fears a spillover of unrest along their shared border.

The 2015 Accord is Crucial to Restoring Peace: The Algeria-brokered talks have played a critical role in overcoming previous crises, notably the 2015 Algiers Accords. Bamako’s current rulers must recognize that only dialogue with their opponents in northern Mali can restore peace.

Mali and Algeria have a Shared Geopolitical Future: A common border, intertwined histories, cross-border family connections, and economic ties demand strengthening Algiers-Bamako relations.

Algeria is Key to Sahel Security: Mali’s junta must recognize the vital role Algeria plays in the stability of the broader Maghreb-Sahel region. While Algeria must carefully navigate its role as a mediator alongside the complexities of Mali’s domestic political landscape.

Introduction

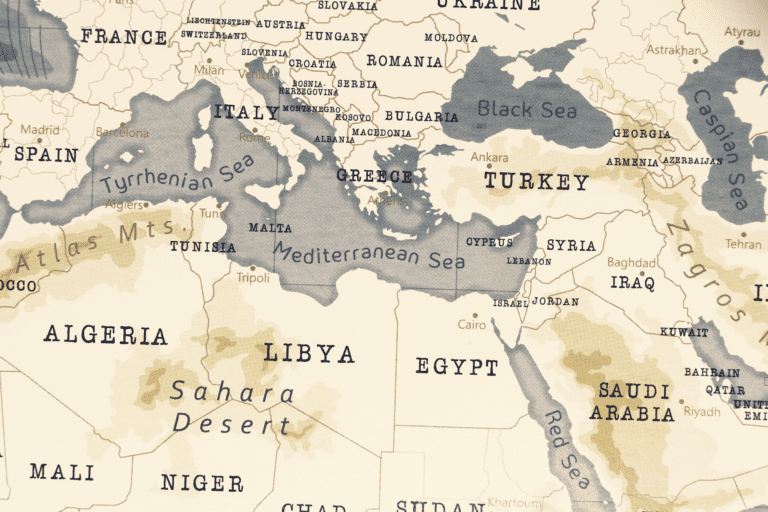

In recent years, Algeria and neighboring Mali have clashed repeatedly, in a string of diplomatic disagreements and security incidents with major implications for stability in the broader Sahel region. The two countries share a porous, 854-mile (1,374-kilometer) border, through a remote desert region that serves as a base for both separatist militants and jihadist groups. In mid-March 2025, a cross-border incident involving the shooting down of a Malian drone sparked a new diplomatic crisis. 1

This issue brief argues that Algiers and Bamako must resume their bilateral relations on a new foundation. Their geographic proximity, linked economies, cross-border Tuareg family ties, and the dire security situation in the Sahel all underscore the closely intertwined future of both countries. Mali’s long-running crisis can be traced back to an uprising by Tuareg armed insurgents who returned from Libya after the fall of Moammar Gaddafi in 2011.2 The Tuareg National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) called for autonomy and even an independent state in the country’s north, bordering Algeria. Its attempt to create one by force resulted in a military coup in Bamako in 2012, which created a power vacuum. This in turn empowered Islamist factions such as the Islamist group Ansar al-Dine which utilized its connections with Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) to seize control of much of the country’s north.3

Algeria viewed this instability with alarm, fearing a potential spillover of militancy into its southern regions—especially among its own Tuareg populations. As the region’s prime military power, Algiers positioned itself as a mediator, leveraging its regional influence and military strength to broker the 2015 Algiers Accord4 between the Malian government and Tuareg communities (along with other minority rebel groups), aimed at restoring peace and stability.

The Algerian-Malian crisis entered a new phase in 2020 with the first of two military coups in Bamako, both led by Colonel Assimi Goïta. The junta he leads today has redirected Mali away from traditional allies such as France—whose Operation Barkhane, launched in 2014 to counter the 2012 uprising, concluded in 2022—and towards Russia, which provides security assistance through the paramilitary Africa Corps, formerly known as the Wagner Group.

Bamako-Algiers relations have since deteriorated. In 2023, Mali withdrew its ambassador to Algeria, under accusations of Algerian interference in Malian internal affairs.5 For Bamako, Algeria’s engagement with Malian political opponents and hosting of Tuareg rebel leaders compromised Mali’s sovereignty and violated the 2015 peace agreement. Consequently, Malian authorities decided to withdraw from the 2015 Algiers Accord in January 2024.6 In December 2024 and January 2025, the junta went further, accusing Algiers of nurturing terrorism in the Sahel.7 Algiers rejected these claims arguing that its historical contributions in reinforcing peace, security, and stability in Mali have always been based on three fundamental principles: “Algeria’s firm respect for Mali’s territorial integrity, sovereignty, and national unity.”8

Algerian authorities have in parallel argued that the presence of Russia’s paramilitary Africa Corps is counter-productive to sustaining peace in Mali and the broader Sahel region. Algiers also called on the United Nations to sanction countries relying on private armies, reportedly in reference to Mali.9 Bilateral relations between both countries are therefore at a standstill with no anticipated improvement. Algeria is directly affected by conflicts in neighboring countries; it therefore arguably has more to gain from peace than other external actors. This reality makes Algeria-Mali cooperation imperative.

Historical Relations

Historically, Algeria has been a crucial stabilizing force in sub-Saharan Africa. Over the past decade, it has focused on addressing instability in Libya, Niger, Mali, and Tunisia, dedicating significant efforts to securing the region and promoting peace. Algeria’s contributions include training special forces, supplying equipment and technical support, and aiding the economic development of Mali and Niger.10

Since Mali and Algeria’s independence in 1960 and 1962, respectively, both countries have maintained an intricate relationship, influenced by their geographical proximity, historical connections, security interests, and economic links. During Algeria’s war of independence against France, Bamako supported Algeria by facilitating the launch of military operations against French troops.11 Today, both countries’ ties are shaped by regional stability, counterterrorism, and economic collaboration. Algeria, a key regional power in North Africa, has been pivotal in mediating conflicts and promoting peace in Mali, while simultaneously enhancing bilateral relations through trade and development efforts. Economically, Mali is highly dependent on aid and imports from Algeria, which include packaged medicines, vaccines, medical instruments, tires, and dates.12

Moreover, Tuareg communities in Algeria and neighboring countries share close tribal ties, with families across borders. The integration of the Tuareg population into Algeria’s national identity is therefore crucial. Any political movement in Mali, Niger, or Burkina Faso advocating for an independent Tuareg state poses a significant threat to Algeria’s own national security, unity, and territorial integrity. Algeria has on various occasions mediated between Bamako and Malian Tuareg factions opposed to the central government, including in the 1990s (leading to the 1991 Tamanrasset Accords following a Tuareg rebellion in 1990), 2006, and 2012.13 Despite these efforts, repeated rebellions indicate that the internal Malian crisis has not been entirely resolved. Yet Algeria continues to play a significant role in Mali.

The 2015 Algiers Accord: Reconciling Malians

Since the 2020 Malian coup, the junta in Bamako has repeatedly accused Algiers of fueling Mali’s internal instability. Malian officials alleged that Algeria either harbors or indirectly supports armed groups, citing its historical ties with Tuareg leaders. They also claim that Algeria shelters and protects Malian rebel groups from the Permanent Strategic Framework for the Defense of the People of Azawad (CSP-DPA) coalition, connections which date back to Algeria’s previous mediation during Tuareg rebellions in the 1990s and 2006–2009. 14

The junta’s resentment partially stemmed from Algeria’s opposition to the coup, and Algiers’ insistence on maintaining relationships with all major actors in Mali, excluding groups viewed as terrorists. In September 2024, at the UN General Assembly, Malian Prime Minister Colonel Abdoulaye Maïga criticized Algeria for interfering in Mali’s politics, declaring the Algiers Accord defunct.15 These remarks overlooked the history of strong cooperation between Algiers and Bamako, particularly after the 2012 coup, when Algeria made significant efforts to help resolve the crisis. 16 At the time, Bamako requested Algeria’s support in mediating between it and its Tuareg opponents.17

Algiers became a key mediator of the intra-Malian dialogue that brokered the Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in Mali, known as the Algiers Accord, signed in April 2015. Soumeylou Boubèye Maïga, Mali’s Prime Minister at the time, noted that “Algeria has always played a major role in Mali’s stability and has intervened at least twice to help establishing inter-Malian peace talks, in 1992 and 2015.”18 In a January 2016 author-led interview, Maïga explained that, following the 2012 insurgency, former President Amadou Toumani Touré urged Algeria to send troops to Mali to fight the militants, which it declined.19 Algiers also refused to use the right of pursuit to track down gunmen fleeing Algeria back into Malian or Nigerien territory.

Algeria’s strategy in addressing the Malian crisis is characterized by a careful balance between principles and pragmatism. Traditionally, Algiers has maintained a policy of non-intervention. This doctrine, and its fear of getting entangled in an intractable conflict, has led it to be cautious about direct military involvement in Mali.20 Instead, it has favored diplomatic efforts, intelligence-sharing, and border security measures to manage threats. In August 2021, then-Minister of Foreign Affairs Ramtane Lamamra reaffirmed21 Algeria’s commitment to the implementation of the 2015 agreement, while leaders of the Malian signatories unanimously reaffirmed their support for the agreement and lauded Algeria’s commitment to Mali.

Algeria’s involvement in Mali is in part motivated by its need to manage its own Tuareg minority. Since the late 1960s, Algeria has integrated the Tuareg into its political system through parliamentary representation and improved their living conditions in southern cities. Preventing Tuareg secession or independence in Mali is vital for Algeria’s national security, due to fears of destabilizing spillover effects. The Algiers Accord offered a framework for lasting peace in Mali, and in 2021, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) recommended that Algeria set up a regional mediation process in the Sahel with the help of the African Union (AU) to continue building trust between Bamako’s central government and domestic opposition.22 In doing so, Algiers would be able to develop a collective process of conflict resolution and peacebuilding with more resources and leverage. Notwithstanding the junta’s withdrawal, the Algiers Accord remains a solid foundation for political stability in Mali. However, it may need to be reviewed and updated.

The Algiers Accord highlighted poor governance and socioeconomic disparities in Mali, which have hindered the country’s political development. It proposed tackling the underlying causes of conflict to foster national reconciliation, emphasizing unity while considering the country’s diverse ethnic landscape.23 The Accord emphasized the importance of strategies to boost economic development in northern Mali, given the region’s geopolitical and sociocultural diversity, and the need for good governance, transparency in public affairs, and combating impunity.24 The challenge lied in the fact that throughout negotiations, both civilian authorities in Bamako and groups such as the Tuareg and Songhai frequently demonstrated reluctance to engage in discussions, until just before the Accord was signed.25 The agreement nevertheless provided a solid foundation for reconciliation within Mali, ensuring its sovereignty, national unity, and territorial integrity. The UN Security Council recognized the deal as crucial for peace and reconciliation in Mali, and urged further dialogue among all its signatories.26.

Despite its potential, many essential aspects of the Algiers Accord remain unimplemented. Carter Center observers have noted “considerable delays” in executing the agreement’s core provisions.27 Five years after the signing of the accord, the UN-supported Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) process had integrated only 1,840 combatants into the national army, out of nearly 85,000 registered by the signatories.28 Additionally, decentralizing governance and implementing essential reforms would enable all Malians, including those from the north, to gain meaningful representation in national institutions.

Economic and Social Ties

Their differences aside, Mali, Algeria, and other Sahelian countries maintain close economic connections. In 2019, Algeria exported $16.3 million worth of goods to Mali, including cement, fertilizers, pasta, and medical instruments.29 In February 2024, Algeria proposed establishing a free trade zone with Mauritania, Tunisia, Libya, Mali, and Niger.30 The free trade zone is intended to enhance regional infrastructure by bolstering public-private partnerships, using national resources, and leveraging development funds and innovative financing. It also aims to boost production capacities, promote the industrial sector, and integrate countries into value-added chains.31

Since 2013, Algeria has repeatedly forgiven the debts of various African nations, including Mali in May 2013. In 2023, Algeria committed $1 billion to development projects throughout Africa.32 These projects include the Trans-Saharan Road Corridor (TSR),33 which is one example of the links between Algeria and Sahel countries. The North-South backbone of the corridor would stretch 2,796 miles (4,500 kilometers), linking the ports of Algiers and Lagos via Algeria, Niger, and Nigeria. An additional 2,858 miles (4,600 kilometers) of connecting highways would reach Tunisia, Mali, Niger, and Chad. About 80% of these TSR roads will be paved.34 Once operational, the TSR will provide landlocked states like Mali and Niger with improved access to the sea. More importantly, it aims to establish a long-term integrated economy among various countries, potentially extending to those along the Gulf of Guinea.35

Algeria and Mali are also exploring energy cooperation: the hydrocarbon-rich Taoudeni basin in northern Mali holds strategic and economic significance for Algeria. Despite regional insecurity delaying exploitation, Mali has issued Algeria’s SONATRACH and its Italian partner, ENI, drill permits.36

Mali and Instability Across the Sahel

The presence of paramilitary groups such as the Africa Corps, as well as other foreign backed groups,37 further complicates relations between Bamako and Algiers. Algeria views the group as a threat both to its own security and to that of the broader region.38 Oil and gas reserves and infrastructure in Algeria’s south is vital to its hydrocarbon-driven economy. Algiers is therefore highly alert towards the threat of armed groups in northern Mali infiltrating and attacking these facilities, particularly considering the February 2013 In Amenas incident, in which Al-Qaeda-linked militants breached the Tinguentourine gas compound and held a number of staff hostage, leading to a siege that left 39 hostages, an Algerian security guard, and all 29 attackers dead.39

The vast deserts of Mali and the wider Sahel region host major security threats in the form of groups such as Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Boko Haram, the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), and Jama’at Nasr al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), among others.40 To address these threats, Algeria supported the Nouakchott Process, launched by the AU in March 2013, which brought together 11 countries41 in the Maghreb, Sahel, and West Africa to promote regional security cooperation.42 This effort resulted in enduring cooperation, even during tensions between neighboring states. In December 2022, the AU’s Peace and Security Council urged West African nations to strengthen collaborative efforts against regional security threats, citing the Nouakchott Process as an example.43 In January 2024, the AU expressed support for revitalizing the mechanism, emphasizing the importance of coordinating efforts at regional and sub-regional levels to combat terrorism and organized crime in the Sahel and other areas.44

Things Fall Apart

In mid-March 2025, a Malian drone strike close to the border destroyed what the army claimed were Algerian-registered trucks carrying aid intended for groups opposed to Bamako.45 The incident underscored Mali’s growing assertiveness in its operations against northern threats, such as Tuareg separatists and jihadists, and highlighted the border region’s instability and use as a channel for smuggling and militancy. Concurrently, Algeria strengthened its military presence along the border, executing operations against jihadists within its broader counterterrorism strategy.46 On April 1 2025, the Algerian military reported the downing of a military drone in the vicinity of Tin Zaouatine, also close to the Malian border.47 Mali confirmed the drone crash, but accused Algeria of shooting it down while it was still in Malian airspace.48

These incidents deteriorated already tense relations. Algeria cited concerns over Mali’s ties to Russian mercenaries and its drone activity near the border; Mali denied it violated its neighbor’s airspace, accused Algeria of backing terrorism, and responded diplomatically by summoning the Algerian ambassador and drafting formal complaints. Algeria insisted that Mali also violated its airspace on two previous occasions, in August and December 2024.49 The members of the Alliance of Sahel States (Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger) recalled their ambassadors from Algeria in April 2025.50 Surprisingly, Mali did not inform Algeria about its aircraft military operations, which is customary between non-belligerent states.51 Additionally, Mali withdrew from the CEMOC, a regional cooperation and security framework involving Algeria, Niger, and Mauritania, mainly aimed at addressing militant threats.52

Pathways Forward

The Algerian-Malian crisis is linked to broader security challenges in the Sahel. The 2023 withdrawal of the UN peacekeeping mission (MINUSMA) and the exit of France have already left a security void that Mali’s junta and its Russian allies have yet to fully address.53 Algeria, wary of a repeat of the 2012 crisis, has therefore stepped up its efforts to secure its southern border.

By alienating Algeria, Mali risks further isolation, having already distanced itself from France and its Western allies. Algeria, as a key regional player and member of the AU, is vital to Mali’s international standing. While Mali has established ties with Russia, the UAE, and the Africa Corps, maintaining good relations with Algeria is essential for regional stability. Long-term, that stability will rest on Mali reconciling its northern and southern regions and Algeria remains well-positioned to assist in this regard.

Conclusion

Since 1963, Algiers has repeatedly mediated between Bamako’s central government and Tuareg movements in the north. Despite implementation flaws, the Algiers Accord has contributed to the stability and the territorial integrity of Mali. With the Sahel today more volatile than ever, Mali must actively work towards restoring stability. In September 2024, Mali’s Foreign Minister Abdoulaye Diop hosted Algeria’s Ambassador Kamel Retieb in Bamako, emphasizing the need for a robust strategic bilateral partnership,54 and affirming that Algeria would continue to support Mali in its search for durable development and for peace, both domestically and in the broader region.

Ties between Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso do not belie the fact that each has distinct internal dynamics and foreign policies. This is highlighted by Niger’s generally close relationship with Algeria—the recent recalling of its ambassador notwithstanding. Niger and Algeria continue to cooperate on economic initiatives, such as the Dosso petrochemical project and Algerian energy giant SONATRACH’s training of personnel from Niger’s SONIDEP.55 This partnership reflects a shared understanding that it is in the interest of all countries in the region to overcome their differences.56

Niamey could serve as a crucial intermediary between Algiers and Bamako to facilitate the resumption of bilateral relations. South Africa, too, could play a significant role due to Pretoria’s longstanding balanced relations with both Algiers and Bamako.57 Algeria, directly affected by regional conflicts, has more to gain from peace than other external actors. Arguably, its non-interventionist doctrine and history of mediating Mali’s conflicts make it an ideal mediator. Despite differences over approaches to rebel groups and regional influence, a pragmatic relationship with Algeria would support Mali’s long-term interests over continued hostility. Mali should avoid allowing the region to become a zone of proxy power struggles between regional or global powers. Given their intertwined futures, Mali and Algeria have a shared interest in improved relations—as do the entire Sahel region and its nations.

Please note that this issue brief was completed by the authors in May 2025 and therefore does not cover recent developments including the reported withdrawal of the Wagner from Mali under Algerian pressure on Moscow, increasing political repression by Mali’s military junta, crackdowns on civil society, and/or other evolving dynamics that have occurred since May 2025.

Endnotes

1 David Ehl, “How an intercepted drone escalated Mali-Algeria tensions,” DW, April 11, 2025, https://www.dw.com/en/how-an-intercepted-drone-escalated-mali-algeria-tensions/a-72216317.

2 Yahia H. Zoubir, “Qaddafi’s Spawn: What the Dictator’s Demise Unleashed in the Middle East,” Foreign Affairs, July 24, 2012, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/mali/2012-07-24/qaddafis-spawn.

3 “Mali Crisis: Key Players,” BBC News, March 12, 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-17582909.

4 “Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in Mali Resulting from the Algiers Process,” United Nations, accessed June 2, 2025, https://www.un.org/en/pdfs/EN-ML_150620_Accord-pour-la-paix-et-la-reconciliation-au-Mali_Issu-du-Processus-d’Alger.pdf.

5 “Mali recalls its envoy in Algeria after alleging interference, deepening tensions over peace efforts,” Associated Press, December 23, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/mali-algeria-ambassador-recall-tuareg-c5a3c71db2d3f1df9dd94b094fb20494.

6 Diakaridia Dembele and Katarina Hoije, “Mali Rebukes Algeria as Peace Accord With Rebels Unravels,” Bloomberg, January 26, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-25/mali-junta-ends-peace-agreement-with-separatist-rebels.

7 Riyad Hamadi, “Algérie – Mali : Bamako franchit la ligne rouge avec un grave dérapage [Algeria – Mali: Bamako Crosses the Red Line with a Serious Misstep],” TSA, January 2, 2025, https://www.tsa-algerie.com/algerie-mali-bamako-franchit-la-ligne-rouge-avec-un-grave-derapage/.

8 Aksil Ouali, “Algérie-Mali : le ministre des Affaires étrangères convoque l’ambassadeur malien à Alger [Algeria-Mali: The Foreign Minister summons the Malian ambassador to Algiers],” Andalou Ajansi, December 12, 2023, https://www.aa.com.tr/fr/afrique/algérie-mali-le-ministre-des-affaires-étrangères-convoque-lambassadeur-malien-à-alger/3089350.

9 “Algeria Calls on UN Security Council to Act in Mali, Genocide Watch,” Genocide Watch, accessed June 2, 2025, https://www.genocidewatch.com/single-post/algeria-calls-on-un-security-council-to-act-in-mali.

10 Lotfi Sour, “Algeria’s Role in the African Sahel: Toward a New Security Paradigm,” International Journal of Euro-Mediterranean Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 155-177, https://emuni.si/ISSN/2232-6022/15.155-177.pdf.

11 “Lamamra: le destin de l’Algérie et celui du Mali sont ‘étroitement liés’[Lamamra: the destiny of Algeria and that of Mali are “closely linked”],” Algerie Presse Service (APS), October 6, 2021, https://www.aps.dz/algerie/128447-lamamra-le-destin-de-l-algerie-est-celui-du-mali-sont-etroitement-lies.

12 Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), “Algeria / Mali,” accessed May 1, 2025, https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/dza/partner/mli. Data on Algerian-Malian trade are not always reliable, especially since there is a significant volume of informal trade across their shared border. For instance, in 2011, the informal sector reached $150 million (see: Sami Bensassi, Anne Brockmeyer, Matthieu Pellerin, and Gaël Raballand, “Commerce Algérie-Mali: La Normalité de l’Informalité [Algeria–Mali Trade: The Normality of Informality],” World Bank, 2015, p. 16,

https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/ba4c7c56-9315-5c2a-b7f5-f42ef12014c3/content. Although rather old, this study remains a good reference to understand the nature of the trade, both formal and informal, between the two countries).

13 For an explanation of these accords and their background, see Khaly-Moustapha Leye, “Médiation algérienne dans la crise malienne : Des faux accords aux désaccords reels [Algerian Mediation in the Malian Crisis: From False Agreements to Real Disagreements…],” Bamada.net, August 26, 2024, https://bamada.net/mediation-algerienne-dans-la-crise-malienne-des-faux-accords-aux-desaccords-reels.

14 Bah Traoré, “Mali-Algérie, une longue histoire d’ambiguïté et de méfiance [Mali-Algeria, a long history of ambiguity and distrust],” Afrique XXI, March 25, 2025, https://afriquexxi.info/Mali-Algerie-une-longue-histoire-d-ambiguite-et-de-mefiance.

15 “Mali announces immediate termination of key Algerian accord amidst growing tensions,” Africa News, January 26, 2024, https://www.africanews.com/2024/01/26/mali-announces-immediate-termination-of-key-algerian-accord-amidst-growing.

16 United Nations, Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation.

17 Nourredine Ayadi, Kidal Vaut Bien Une Guerre: L’Algérie et la France au Mali et au Sahel. Influence vs Puissance [Kidal is Worth a War: Algeria and France in Mali and the Sahel. Influence vs Power] (Algiers: Editions El Qobia, 2024), pp. 297-298.

18 “Mali hails Algeria’s key role in its stability,” Xinhua, January 14, 2018, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-01/14/c_136893648.htm.

19 Soumeylou Boubèye Maïga (former prime minister), interview by author, Algiers, Algeria, January 2016.

20 National security officials, interview by author, Algiers, Algeria, 2016 and 2017.

21 Yahia H. Zoubir and Abdelkader Abderrahmane, “Alger au Sahel : Stabilité et sécurité [Algiers in the Sahel: Stability and Security],” Politique Étrangère, no. 2 (June 2022): 128, https://www.revues.armand-colin.com/eco-sc-politique/politique-etrangere/politique-etrangere-ndeg-22022/alger-au-sahel-stabilite-securite.

22 Virginie Baudais, Amal Bourhrous, and Dylan O’Driscoll, Conflict Mediation and Peacebuilding in the Sahel, Policy Paper, (Stockholm, Sweden: SIPRI, January 2021), 35, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/sipripp58_3.pdf.

23 Gaudence Nyirabikali, “The Mali peace process and the 2015 peace agreement,” in “The Implementation of the Peace Process in Mali,” SIPRI Yearbook 2016, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/SIPRIYB16c05sIII.pdf.

24 Ibid.

25 Ayadi, Kidal Vaut Bien Une Guerre.

26 “Mali: UN Security Council Calls For Resumption of Dialogue in Bamako to Implement Algiers Agreement,” West Africa Democracy Radio, January 9, 2024, https://wadr.org/mali-un-security-council-calls-for-resumption-of-dialogue-in-bamako-to-implement-algiers-agreement/.

27 “Mali Independent Observer: Little Progress in Implementing Peace Agreement in 2020, but Transition Offers New Opportunity,” The Carter Center, December 16, 2020, https://www.cartercenter.org/news/pr/2020/mali-121620.html.

28 “Mali’s Algiers Peace Agreement, Five Years On: An Uneasy Calm,” International Crisis Group, June 24, 2020, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali/laccord-dalger-cinq-ans-apres-un-calme-precaire-dont-il-ne-faut-pas-se-satisfaire.

29 OEC, “Algeria/Mali.”

30 “L’Algérie projette de créer une zone franche avec la Mauritanie, la Tunisie, la Libye, le Mali et le Niger [Algeria plans to create a free trade zone with Mauritania, Tunisia, Libya, Mali, and Niger],”

February 15, 2024, Agence Ecofin, https://www.agenceecofin.com/transports/1402-116188-l-algerie-envisage-de-creer-une-zone-franche-avec-la-mauritanie-la-tunisie-la-libye-le-mali-et-le-niger.

31 Dalila Hanache, “President Tebboune: Algeria to Create Free Trade Zones With 5 African Countries in 2024,” Echoroukonline, February 24, 2024, https://www.echoroukonline.com/president-tebboune-algeria-to-create-free-trade-zones-with-5-african-countries-in-2024.

32 Mustafa Dala, “Que vise l’Algérie avec son aide au développement d’un milliard de dollars à l’Afrique? [What is Algeria aiming for with its $1 billion development aid to Africa?]” Anadolu Ajansi, March 3, 2023, https://www.aa.com.tr/fr/afrique/que-vise-lalgérie-avec-son-aide-au-développement-dun-milliard-de-dollars-à-lafrique-/2836180.

33 Also known as the Trans-Sahara Highway.

34 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, The Trans-Saharan Road Corridor. Towards an Economic Corridor: Commercializing and Managing the Trans-Saharan Road, (Geneva, Switzerland: UNCTAD, 2022),14, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tcsdtlinf2022d2_en.pdf.

35 Ibid.

36 Bah Traoré, “Mali-Algérie, une longue histoire d’ambiguïté et de méfiance [Mali-Algeria: A Long History of Ambiguity and Mistrust],” Afrique XXI, March 25, 2025, https://afriquexxi.info/Mali-Algerie-une-longue-histoire-d-ambiguite-et-de-mefiance.

37 Jean-Pierre Filiu, “La stratégie séparatiste des Emirats arabes unis [The separatist strategy of the United Arab Emirates],”Le Monde, May 11, 2025, https://www.lemonde.fr/un-si-proche-orient/article/2025/05/11/la-strategie-separatiste-des-emirats-arabes-unis_6604934_6116995.html.

38 “Le groupe Wagner est ‘une menace pour l’Algérie [The Wagner Group is “a threat to Algeria”],” Le Matin d’Algérie, September 2, 2024, https://lematindalgerie.com/le-groupe-wagner-est-une-menace-pour-lalgerie/.

39 Geoff D. Porter, “Terrorist Outbidding: The In Amenas Attack”, CTC Sentinel, May 2015, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/terrorist-outbidding-the-in-amenas-attack/.

40 “Violent Extremism in the Sahel,” Council on Foreign Relations, accessed June 2, 2025, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violent-extremism-sahel.

41 Namely: Algeria, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal and Chad.

42 International Crisis Group, Algeria and Its Neighbours, Middle East and North Africa Report (Brussels, Belgium: International Crisis Group, October 2015), https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/north-africa/algeria/algeria-and-its-neighbours.

43 “Decision on the Report on the Activities of the Peace and Security Council (PSC) and the State of Peace and Security in Africa,” Data for Governance Alliance, accessed June 2, 2025, https://africanlii.org/akn/aa-au/statement/decision/au-assembly/2022/815/eng@2022-02-06.

44 “Joint A-3 Plus Statement on the Situation in Western Africa and the Sahel,”African Union, January 11, 2024, https://www.africanunion-un.org/post/joint-a-3-plus-statement-on-the-situation-in-western-africa-and-the-sahel.

45 Mohammed Jaabouk, “Mali’s military reacts to Akinci drone downing in Sahel,” Yabiladi, April 3, 2025, https://en.yabiladi.com/articles/details/163086/mali-s-military-reacts-akinci-drone.html.

46 “Algerian army kills 2 foreign militants near Mali-Niger border,” Xinhua, March 22, 2025, https://english.news.cn/20250322/0c70b118ef16441399d2b6dcd6fd64f8/c.html.

47 “Algerian Army Downs Turkish-Made Drone Near Border, Mali Claims Ownership,” Watan News, April 2, 2025, https://www.watanserb.com/en/2025/04/02/algerian-army-downs-turkish-made-drone-near-border-mali-claims-ownership/.

48 “Le Mali, le Niger et le Burkina Faso rappellent leurs ambassadeurs en Algérie après un incident avec un drone [Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso recall their ambassadors from Algeria after a drone incident],” Le Monde, April 7, 2025, https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2025/04/07/le-mali-le-niger-et-le-burkina-faso-rappellent-leurs-ambassadeurs-en-algerie-apres-un-incident-de-drone_6592160_3212.html.

49 Algerian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Communiqué de presse du Ministère des Affaires étrangères – Confédération des Etats du Sahel 07/04/2025 [Press Release from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs – Confederation of Sahel States],” April 7, 2025, https://www.mfa.gov.dz/fr/announcements/statement-of-the-ministry-of-foreign-affairs-confederation-of-sahel-states-07042025.

50 “Les États membres de l’AES rappellent leurs ambassadeurs en Algérie [The member states of the AES recall their ambassadors from Algeria],” RFI, April 7, 2025, https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20250407-les-%C3%A9tats-membres-de-l-aes-rappellent-leurs-ambassadeurs-en-alg%C3%A9rie.

51 Algerian official (anonymous), interview by author (by phone), April, 2025.

52 Zakaria S, “Drone abattu : l’Algérie répond fermement et réfute les accusations du Mali [Downed drone: Algeria responds firmly and refutes Mali’s accusations],” Algerie360, April 7, 2025, https://www.algerie360.com/drone-abattue-lalgerie-repond-fermement-et-refute-les-accusations-du-mali/.

53 Caroline Rose and Tammy Palacios, “French Withdrawal and the Security Landscape of the Sahel: Podcast” New Lines Institute, March 12, 2025, https://newlinesinstitute.org/state-resilience-fragility/french-withdrawal-and-the-security-landscape-of-the-sahel/.

54 Mantia Touré, “Nouveau Chapitre pour les Relations Mali-Algérie : L’Ambassadeur Algérien Présenté à Bamako [New Chapter for Mali-Algeria Relations: The Algerian Ambassador Presented in Bamako],” September 14, 2024, Mali Actu, https://maliactu.net/nouveau-chapitre-pour-les-relations-mali-algerie-lambassadeur-algerien-presente-a-bamako/.

55 El Houari Dilmi, “Algérie, Niger et Nigeria: Prochaine réunion sur le projet du gazoduc transsaharien [Algeria, Niger, and Nigeria: Upcoming meeting on the Trans-Saharan gas pipeline project],” Le Quotidien d’Oran, October 1, 2024, https://www.lequotidien-oran.com/index.php?news=5332729.

56 Helene Sourou, “Algérie-Niger : Stabilité régionale au cœur des échanges [Algeria-Niger: Regional stability at the heart of discussions],” Journal du Niger, August 12, 2024, https://www.journalduniger.com/algerie-niger-stabilite-regionale-au-coeur-des-echanges/.

57 “Algeria-Mali: Defusing a Dangerous Escalation,” International Crisis Group, April 18, 2025, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali-algeria/algerie-mali-desamorcer-une-dangereuse-escalade.