Strategic Transactionalism:

The Iran-Russia Partnership

Issue Brief, June 2025

Key Takeaways

Systemic Pressures and Convergence: The evolving partnership between Iran and Russia is largely shaped by systemic pressures, particularly tensions with the West, which have pushed both sides into greater military, economic, and political interdependence.

Limits to Alliance: Diverging revisionist agendas, distinct threat perceptions, economic limitations, and third-party considerations prevent the partnership from becoming a full-fledged, comprehensive alliance.

Cooperation and Caution: While the partnership is unlikely to revert to purely transactional dynamics, its future trajectory will depend on key drivers affecting Tehran and Moscow’s respective calculations, such as U.S. policies, regional conflicts, and leadership changes.

Strategic Transactionalism: The Iran-Russia relationship combines pragmatic, interest-driven cooperation with growing ambitions for deeper strategic alignment, yet remains constrained by enduring limitations and competing priorities.

Introduction

On January 17, 2025, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Treaty in Moscow. The agreement is aimed at strengthening bilateral relations over the next 20 years.1 Reportedly delayed by the death of Pezeshkian’s predecessor Ebrahim Raisi in May 2024 and disagreements over details, the treaty came at a time of heightened geopolitical tensions for both countries and was hailed by officials in Tehran and Moscow as a sign of deepening strategic alignment. While the treaty signals a shift away from the purely transactional nature that has long defined Tehran-Moscow ties, their partnership remains complex and far from a full-fledged alliance. To understand this dynamic, it is crucial to examine the structural factors driving closer ties, as well as the enduring constraints limiting the depth of their cooperation.

The primary force behind the evolving Iran-Russia partnership is systemic pressure—particularly the mounting tensions between both countries and the West. Russia’s deteriorating relations with Western powers, exacerbated first by the 2014 Crimea crisis then by Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, have pushed Moscow to seek stronger ties with states willing to challenge Western influence.

Iran faces similar pressures. Western sanctions, diplomatic isolation, and its ongoing confrontation with Israel, which Tehran views as part of a broader struggle against Western hegemony, have heightened its security concerns.2 Against this backdrop, Iran and Russia have expanded their cooperation, finding common ground in their opposition to the liberal international order and their shared need for alternative economic and military partnerships.

Despite their growing convergence, Iran and Russia’s partnership remains constrained by key structural factors. While both countries share an interest in challenging what they perceive as a Western-dominated global order, their revisionist agendas differ in both scope and strategy. Iran’s opposition to the U.S.-led international system is rooted in ideological hostility, driven by its revolutionary outlook. By contrast, Russia has historically adopted a more pragmatic approach, shaped by its desire for recognition as a major global power.3

This divergence has often led Moscow to pursue deals with Western powers that have sidelined Iranian interests. Even as Russia’s ties with the West deteriorate, Moscow continues to balance its relationship with Tehran with its ties with other regional actors, such as Israel and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states. Similarly, Iran’s efforts to maintain some engagement with Europe introduce another layer of caution to its partnership with Russia. This issue brief therefore argues that the Iran-Russia relationship is best understood as a partnership in transition, which has moved beyond mere transactionalism, but has yet to emerge as a full-fledged strategic alliance.

By examining the current geopolitical context, the content and limitations of the recent strategic treaty, and potential future scenarios, this issue brief aims to provide a comprehensive assessment of the future trajectory of Iran-Russia relations.

Driven Together by Geopolitics

Tehran and Moscow’s evolving partnership has been shaped by systemic pressures stemming from major regional and global geopolitical developments over the past decade. Russia’s deteriorating ties with the West, particularly after its annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its 2022 war on Ukraine, played a pivotal role in Moscow’s strategic reorientation. These events triggered unprecedented Western sanctions against Russia’s energy exports, financial institutions, and access to global markets. In response, Moscow actively sought closer ties with non-Western states to reduce its economic dependence on Western systems.4 Strengthening its partnership with Iran became a key component of this strategy, particularly given Tehran’s own experience with Western sanctions and diplomatic isolation.

The systemic pressures on Iran intensified following the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal, in 2018. The Trump administration’s subsequent maximum pressure campaign severely restricted Iran’s oil exports and international financial transactions, causing significant economic hardship. Iranian oil exports, which had peaked at approximately 2.5 million barrels per day (bpd) in 2017, plummeted to below 400,000 bpd by 2020.5

Although the Biden administration adopted a less aggressive stance, it maintained most of the sanctions—and the resultant economic strain. This prolonged pressure pushed Tehran to pivot eastward, strengthening ties with Russia and China to secure economic support and political backing.6 Iran’s deepening involvement in multilateral organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and BRICS+ reflected this strategic shift; by 2025, Tehran became a full member of both. Tehran views Russia and China as key players in an emerging multipolar world order, and has therefore prioritized strengthening relations with them at both the bilateral and multilateral levels.

Russia’s war on Ukraine further accelerated their alignment. As Russia faced mounting military and economic challenges, it turned to Iran for assistance in procuring and jointly producing drones, which it subsequently deployed in Ukraine. In return, Russia reportedly expanded cooperation with Iran in military technology, intelligence sharing, and technical support.7 Moscow has also facilitated Iran’s defense cooperation with traditional Russian allies, such as Belarus and Tajikistan, further reinforcing the partnership.8

The war on Gaza has also been a significant driver of stronger Iran-Russia relations.9 From Tehran’s perspective, this conflict extends beyond a regional dispute; Iranian leaders view it as part of the same systemic pressures that have shaped Iran’s overall geopolitical stance. In their view, Israel’s aggressive actions in Gaza and beyond reflect a Western, particularly U.S.-led, agenda to reshape the Middle East’s regional order—an agenda that must be countered.

In this context, Russia’s increasingly vocal criticism of Israel’s war on Gaza has aligned with Iran’s longstanding narrative, further cementing their partnership. From the outset of the war, Moscow supported calls for a ceasefire and opposed Western-backed resolutions that unconditionally favored Israel, aligning with Tehran’s diplomatic stance.10 The war also created an opportunity for Russia to expand its engagement with Iran’s regional allies in the Axis of Resistance, including Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen.11

Simultaneously, Israel’s war on Gaza has significantly weakened Iran’s regional network, exacerbated by over a year of hostilities and direct military confrontations between Iran and Israel (in April and October 2024).12 All this heightened Tehran’s sense of urgency to bolster its offensive and defensive military capabilities. Moscow has emerged as Iran’s main partner in that regard, particularly in Tehran’s efforts to acquire advanced air defense systems such as the S-400 surface-to-air missile system and Russian Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets, weapons Moscow has long been reported to be planning to deliver to Tehran.13

Both countries have also expanded their economic cooperation in response to their shared isolation from the global system. They have worked to develop alternative financial mechanisms to bypass Western sanctions and boost commerce. By 2022, their bilateral trade had reached approximately $5 billion, a notable increase since the start of the Ukraine war.14 Their collaboration within the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), along with joint infrastructure projects and energy initiatives, also reflects this effort. A case in point is the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) between Russia, Iran, and India, creating a vital link between the Gulf and Northern Europe.15 This corridor is intended to enhance regional trade and connectivity, reducing reliance on Western trade routes.

Yet these ties remain modest compared to other aspects of their partnership, as well as in relation to Russia’s economic ties with other regional powers such as Türkiye and the Gulf states. Moreover, multilateral initiatives like the INSTC have made slow progress due to limited financial resources for infrastructure development and the political complexities surrounding third-party involvement.

The Strategic Partnership Treaty

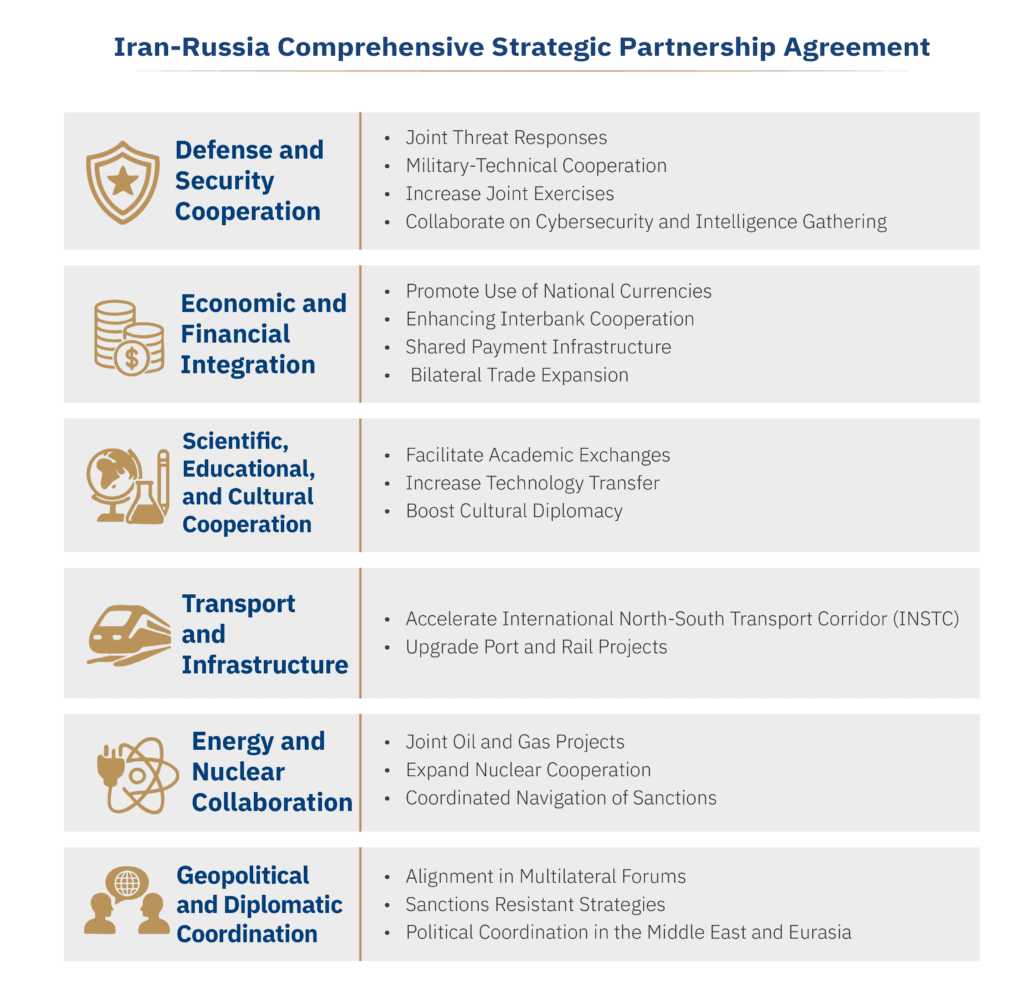

The “Treaty on the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Russian Federation” reflects the evolving nature of Iran and Russia’s relationship, in terms of both opportunities and limitations. The 20-year agreement, comprising 47 articles, outlines cooperation across various sectors, including security, energy, trade, and cultural exchange.16 While it establishes a framework for expanding bilateral ties, its contents reveal a deliberate effort by both sides to deepen cooperation in selected areas without committing to a full-fledged alliance.

In the security domain, the treaty emphasizes collaboration in the defense industries, military training, and intelligence-sharing. It also includes provisions for joint military exercises aimed at enhancing operational coordination. However, the absence of a mutual defense clause—a hallmark of stronger military alliances—is particularly notable. This omission reflects Russia’s reluctance to entangle itself in Iran’s regional disputes, particularly Tehran’s ongoing conflict with Israel. Moscow’s careful balancing of relations with Iran’s key rivals and adversaries, including Israel and several Gulf states, underscores its strategic restraint.

While Russia has signaled greater alignment with Iran in the Middle East in recent years, it continues to maintain pragmatic ties with the Gulf states and Israel. This limits the depth of its strategic commitment to Tehran. Russia has maintained communication with Israel over Syria even after the fall of the Assad regime, and recent reports suggest that Israel is lobbying the United States to allow Russia to maintain military bases in Syria as a counterbalance to growing Turkish influence.17

Moscow has also supported the Emirati—and GCC—position on the three Gulf islands disputed between Iran and the UAE.18 This stance underscores Russia’s careful balancing act in the region, which seeks to secure energy cooperation and economic ties with the GCC states, even at the expense of Iranian interests. For Tehran, the absence of a binding defense commitment in the partnership treaty reflects a pragmatic recognition that Moscow is unwilling to jeopardize its broader regional interests for closer alignment with Iran. Additionally, Tehran, already facing diplomatic backlash from key European states for supporting Russia in the Ukraine war, is cautious about escalating tensions further by formalizing a military alliance with Moscow and deepening its involvement in the broader Russia-Europe conflict.

The treaty’s economic provisions also demonstrate a mix of alignment and caution. It advocates for increased bilateral trade, promotes the use of national currencies in place of the U.S. dollar, and highlights collaboration in infrastructure and energy sectors. The commitment to increasing trade in national currencies clearly aims to reduce reliance on Western financial systems and mitigate the impact of sanctions. However, the economic provisions lack clear detail regarding their scope. Although the treaty emphasizes energy cooperation, including potential joint ventures in oil, gas, and nuclear energy, it stops short of committing to significant investments or large-scale infrastructure projects. This ambiguity may reflect Russia’s continued prioritization of its economic ties with wealthier Gulf producers, whose energy markets offer greater profitability and stability than Iran’s. Moscow’s close cooperation with these states within the OPEC+ framework further underscores this strategic focus.19

Financial constraints remain another significant obstacle to meaningful investment in joint projects, further complicating implementation of the treaty’s economic provisions. This mix of constrained economic capacity and Russia’s diversified energy partnerships underscores the practical limits of Moscow’s economic involvement with Tehran. The most realistic area of economic partnership appears to be joint projects in energy and the nuclear sector, along with cooperation in multilateral economic initiatives—initiatives already in progress at various levels.

Ultimately, the treaty reflects a growing alignment between Tehran and Moscow, driven by shared opposition to Western pressure and mutual economic and military interests. However, it also highlights the limits of their cooperation, shaped by strategic caution and competing priorities.20 In essence, the treaty reflects the current state of their bilateral relationship rather than signaling a significant breakthrough. While it formalizes their growing interdependence, it also reinforces the pragmatic nature of their relationship: a partnership defined by immediate strategic utility, rather than a long-term, comprehensive alliance.

Future Scenarios

While systemic pressures have drawn Tehran and Moscow closer together, the durability and scope of their partnership remain uncertain. Its future will be shaped by a combination of international developments, regional dynamics, and internal political shifts.21

A critical variable is the future of each country’s relationship with the West. A potential rapprochement between either Iran or Russia and the United States could significantly alter their respective strategic calculus. For instance, if ongoing high-level contacts between Washington and Moscow were to result in a concrete agreement, likely tied to a ceasefire in Ukraine and a reduction in U.S. sanctions on Russia, Moscow’s reliance on military cooperation and alternative economic partnerships with countries like Iran could diminish. In such a scenario, Russia may reduce its emphasis on ties with Tehran, particularly if restoring relations with the West became a priority for stabilizing its broader international position.

On the other hand, if Iran were to reach an agreement with the United States on its nuclear program in exchange for a reduction in economic sanctions, Tehran could recalibrate its relationship with Moscow. Historically, Iran has sought to avoid overdependence on any single power. A renewed Western diplomatic channel could reduce Tehran’s urgency to deepen ties with Russia, prompting a more balanced approach between East and West.

To mitigate the risk of losing influence over Tehran, Russia has already taken diplomatic steps toward leveraging its improving ties with the Trump administration to mediate a nuclear agreement between Iran and the United States.22 If successful, Moscow could present such an agreement as a concession to Trump in exchange for U.S. flexibility on Ukraine, while simultaneously preserving its influence over Iran’s foreign policy and nuclear program. By facilitating a bilateral deal between Tehran and Washington, Russia could also sideline European powers, weakening their diplomatic influence in the process.

Aware of these complexities, Iran has chosen Oman—its traditional mediator with the United States—to facilitate its dialogue with Washington. At the same time, Tehran has intensified high-level contacts with Moscow, as well as Beijing, regarding the nuclear file.23 On the one hand, this move seeks to reassure both powers that even an agreement with the United States will not undermine Iran’s close relations with them. On the other hand, Iranian officials are using these ties and the backing of Russia and China as leverage in negotiations with Washington.

Another possible scenario would involve a further escalation of tensions pitting Iran and Russia against Western powers. Should diplomatic rifts deepen, whether through tighter Western sanctions on Russia or increased pressure on Iran, Tehran and Moscow could be driven into even closer strategic alignment. In such a situation, their cooperation could expand into more sensitive areas, including advanced arms transfers and coordinated diplomatic efforts to counter Washington’s influence in the Middle East. Ultimately, the extent to which the security-military and geopolitical dimensions of the Iran-Russia partnership strengthen will depend heavily on the level of tension in their respective ties with the West. As friction with Western powers intensifies, the incentives for closer cooperation between Tehran and Moscow are likely to grow.

Domestic political developments in either Iran or Russia could also significantly influence the trajectory of their partnership. In Iran, the eventual transition from Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s leadership represents a potential inflection point. While the Islamic Republic’s ideological foundations are likely to persist, a new leader may reassess the country’s strategic priorities. Should Iran’s future leadership pursue renewed diplomatic engagement with the West, the urgency to deepen ties with Moscow could diminish. Similarly, leadership changes in Russia could recalibrate Moscow’s foreign policy. While Vladimir Putin has prioritized closer ties with Iran as part of his broader anti-Western posture, a successor seeking to reduce Russia’s international isolation may pursue diplomatic openings with Western states. Such a shift could weaken strategic engagement between Russia and Iran.

Despite these potential changes, a full rollback of the Iran-Russia partnership remains unlikely. Systemic pressures, including Western sanctions, military threats, and broader efforts to marginalize both countries, provide a strong foundation for continued cooperation. Moreover, recent efforts to institutionalize their relationship, such as the 2025 Strategic Partnership Treaty and their engagement in multilateral forums, have fostered a degree of structural interdependence. As such, even if diplomatic openings with the West emerge, it is unlikely that either country would entirely abandon its relationship with the other. Instead, their partnership may shift back toward a more flexible, transactional arrangement that balances cooperation with strategic caution.

After all, geography and strategic realities will remain key factors. As neighbors via the Caspian Sea, Iran and Russia cannot ignore each other’s regional considerations. Even before the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the Shah of Iran, despite aligning with the Western bloc, consistently sought to balance his country’s relations with both the United States and the Soviet Union.24

Conclusion

The evolving partnership between Iran and Russia is a complex and calculated alignment shaped by systemic pressures, mutual needs, and strategic caution. While it has moved beyond a purely transactional form of cooperation, it has yet to mature into a full-fledged strategic alliance. Instead, the partnership can best be described as strategic transactionalism, a relationship that combines pragmatic, interest-driven cooperation with growing ambitions for deeper strategic alignment—which nonetheless remain constrained by enduring limitations and competing priorities. Strategic transactionalism suggests a calculated balance: moving beyond short-term transactions toward deeper cooperation in long-term strategic domains, yet maintaining a relationship defined by caution, flexibility, and the enduring influence of broader geopolitical realities.

The Strategic Partnership Treaty underscores this dynamic. While it formalizes cooperation in key areas such as defense, energy, and trade, it avoids binding commitments that would characterize a full strategic alliance. At the same time, it grants both Tehran and Moscow the strategic flexibility they seek in order to balance their relationships with third actors. Yet this cautious approach does not diminish the significance of their relationship. Systemic pressures have created conditions that are pushing Tehran and Moscow toward deeper cooperation, and that will continue to shape the intensity and trajectory of the partnership in the future. Meanwhile, the two countries have institutionalized elements of cooperation that are likely to endure even if diplomatic openings with the West emerge.

Looking ahead, the evolving alignment between Tehran and Moscow will likely continue to operate on a spectrum between transactional cooperation and strategic coordination, advancing in selective areas of mutual benefit while avoiding the risks of overcommitment. Ultimately, the Iran-Russia partnership stands as a model of pragmatic alignment in a shifting global landscape: one in which systemic pressure may push adversaries closer together, even as the limits to their cooperation remain firmly in place.

Endnote

1 “Key Provisions of Russia-Iran Strategic Cooperation Treaty,” Reuters, January 17, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/key-provisions-russia-iran-strategic-cooperation-treaty-2025-01-17/.

2 Maziar Motamedi, “Iran and Israel: From Allies to Archenemies, How Did They Get Here?” Al Jazeera, November 6, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/11/6/iran-and-israel-from-allies-to-archenemies-how-did-they-get-here.

3 Dmitry V. Yefremenko, “The Sources of Russia’s Great-Power Status,” Russia in Global Affairs, no. 1 (January/March 2025), https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/great-russia-yefremenko/.

4 Max Bergmann, Hanna Notte, and Jon B. Alterman, “Understanding the Growing Collaboration Between Russia and Iran,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), June 12, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/understanding-growing-collaboration-between-russia-and-iran.

5 “Iran’s Crude Oil Production Fell to an Almost 40-Year Low in 2020,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, August 12, 2021, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=49116.

6 Hamidreza Azizi, Iran’s “Look East” Strategy: Continuity and Change under Raisi, (Doha, Qatar: Middle East Council on Global Affairs, September, 2023), https://mecouncil.org/publication/irans-policy-and-its-relations-with-china-and-russia-me-council/.

7 Javad Heiran-Nia, “The Roots of Increasing Military Cooperation Between Iran and Russia,” Stimson Center, October 16, 2024, https://www.stimson.org/2024/the-roots-of-increasing-military-cooperation-between-iran-and-russia/.

8 Jack Roush, “Russia’s War in Ukraine Has Brought Iran and Belarus Closer Together,” War on the Rocks, February 17, 2025, https://warontherocks.com/2025/02/russias-war-in-ukraine-has-brought-iran-and-belarus-closer-together/.

9 Hamidreza Azizi, “Allied against the West,” International Politics and Society, March 12, 2024, https://www.ips-journal.eu/topics/foreign-and-security-policy/allied-against-the-west-7384/.

10 “Russia Says Israel’s Gaza Bombardment Is against International Law,” Reuters, October 28, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/russia-says-israels-gaza-bombardment-is-against-international-law-2023-10-28/.

11 Hamidreza Azizi and Hanna Notte, “Russia’s Dangerous New Friends: How Moscow Is Partnering with the Axis of Resistance,” Foreign Affairs, February 14, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/russias-dangerous-new-friends.

12 Farzin Zandi, “How Iran Lost Before It Lost: The Roll Back of Its Gray Zone Strategy,” War on the Rocks, January 24, 2025, https://warontherocks.com/2025/01/how-iran-lost-before-it-lost-the-roll-back-of-its-gray-zone-strategy/.

13 “Iran’s Revolutionary Guards Commander Says Iran Purchased Russian-Made Sukhoi 35 Fighter Jets,” Reuters, January 27, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/irans-revolutionary-guards-commander-says-iran-purchased-russian-made-sukhoi-35-2025-01-27/.

14 “Trade Turnover Between Russia, Iran Up 20% in 2022 to $4.9 Billion, Says Chamber of Commerce,” TASS, March 1, 2023, https://tass.com/economy/1583367.

15 Umud Shokri, “North-South Transport Corridor: Iran-Russia New Railway to Circumvent Western Pressure,” Gulf International Forum, May 3, 2023, https://gulfif.org/north-south-transport-corridor-iran-russia-new-railway-to-circumvent-western-pressure/.

16 “Full Text of Iran-Russia Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement,” Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran, January 17, 2025, https://irangov.ir/detail/456479.

17 Maya Gebeily and Humeyra Pamuk, “Exclusive: Israel Lobbies US to Keep Russian Bases in a ‘Weak’ Syria, Sources Say,” Reuters, February 28, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/israel-lobbies-us-keep-russian-bases-weak-syria-sources-say-2025-02-28/.

18 Sabena Siddiqui, “Russia’s Iran-UAE Balancing Act in the Gulf Islands Dispute,” The New Arab, January 10, 2024, https://www.newarab.com/analysis/russias-iran-uae-balancing-act-gulf-islands-dispute.

19 Nikolay Kozhanov, “OPEC+: Locked in a Russia-US-Saudi Triangle,” Middle East Institute, December 8, 2021, https://www.mei.edu/publications/opec-locked-russia-us-saudi-triangle.

20 Nikita Smagin, “New Russia-Iran Treaty Reveals the Limits of Their Partnership,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 21, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/russia-eurasia/politika/2025/01/russia-iran-strategic-agreement?lang=en.

21 Mathieu Droin and Nicole Grajewski, “Iran, Russia, and the Challenges of ‘Inter-Pariah Solidarity,’” War on the Rocks, July 11, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/07/iran-russia-and-the-challenges-of-inter-pariah-solidarity/.

22 “Russian Offer to Mediate Talks with Trump Spurs Expressions of Mistrust in Iran,” Amwaj Media, March 6, 2025, https://amwaj.media/en/media-monitor/russian-offer-to-mediate-talks-with-trump-spurs-expressions-of-mistrust-in-iran.

23 “China, Russia and Iran Jointly Discuss Iran’s Nuclear Programme with IAEA, Reports Xinhua,” Reuters, April 25, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/china-russia-iran-jointly-discuss-irans-nuclear-programme-with-iaea-reports-2025-04-24/.

24 “The Shah to the Soviet Union: As Long as I Am Alive, There Will Be No Threat to You,” Islamic Revolution Document Center, November 24, 2024 (in Persian), https://irdc.ir/0002VK.