Hezbollah’s Defeat and Iran’s Strategic Depth Doctrine

Issue Brief, April 2025

Key Takeaways

Hezbollah was Vital to Iran’s ‘Strategic Depth’: For decades, Iran invested heavily in Hezbollah and other regional armed groups as an extraterritorial deterrent to U.S. and Israeli threats against the Islamic Republic.

Israel has Severely Weakened the Movement: Sustained Israeli attacks since October 7, 2023, have severely curtailed Hezbollah’s military capacities, and by extension, Iran’s strategic depth.

Iran Has Few Options for Reviving Hezbollah: Tehran’s dire economic situation, the fall of the Assad regime, and Donald Trump’s return to the White House all challenge Iran’s efforts to revitalize its Lebanese ally.

Tehran’s Regional Strategy Persists: Iranian officials have sought to spin the defeat as a victory, indicating that Tehran will continue its strategy of fostering regional allied groups.

Introduction

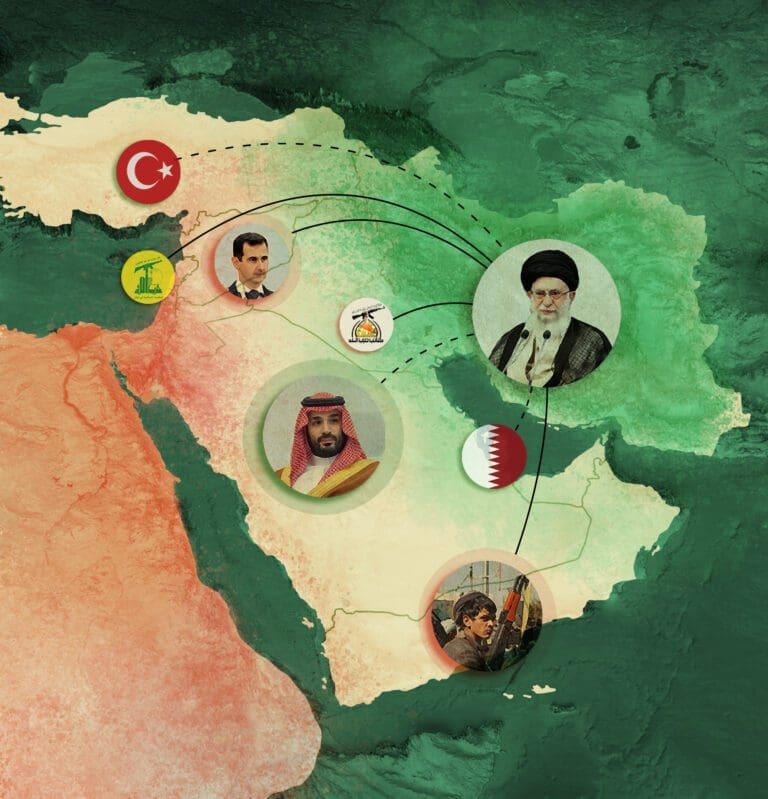

In 2024, Iran’s efforts to gain strategic depth in the Middle East suffered a series of crippling blows. For decades, the Islamic Republic extended patronage to Hamas in the Gaza Strip and Hezbollah in Lebanon, and came to Bashar al-Assad’s aid from 2011 onwards to protect his regime in Syria against armed rebel groups. This strategy, initially aimed at expanding Iran’s regional influence, morphed into a network of deterrence to ward off U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iranian soil.

Today, this strategy lies in ruins. The war on Gaza has changed Iran’s calculus and dragged it into an unprecedented direct military exchange with Israel. With the retreat or collapse of its major regional allies, Iran’s broader strategic landscape has shifted rapidly. Perhaps the most consequential of those defeats was that of Hezbollah. The Lebanese movement had been established in the 1980s, under Iranian patronage, in response to Israel’s occupation of Lebanon. Hezbollah’s performance in the 2006 war served as a model of resistance against Israel, which both inspired and demonstrated the importance of a coordinated “Axis of Resistance.” Iran’s leadership invested heavily in nurturing and sustaining Hezbollah over the years, using Iraqi and Syrian territory as a land corridor to supply it with weapons and technology.

When Israel launched its onslaught on Gaza in October 2023, Hezbollah responded with its own barrages of missiles across the Lebanese border. This policy, in support of Hamas and in line with Iranian policy, aimed to divert Israel’s resources from the Gaza front and ultimately bring an end to the war. In September 2024, Hezbollah’s then-Secretary General Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah declared that Hezbollah would not rest until Israel had ended its war on Gaza.1Just days after that statement, Nasrallah himself was killed in a major Israeli airstrike, and in November 2024, Hezbollah agreed to a ceasefire with Israel, which involved withdrawing from the border area to the north of the Litani River.2 In strategic terms, this signaled both a major defeat and a decoupling of Hezbollah from Hamas.

Assad’s fall in early December 2024 at the hands of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham added to Tehran’s woes, further challenging its ability to project regional power—particularly by depriving it of access to the land corridor needed to replenish Hezbollah’s arsenal. These developments amount to a series of dramatic setbacks for Iran’s grand design to gain strategic depth by cultivating a network of allied actors across the region. The heaviest of those blows was to Hezbollah. This issue brief examines the movement’s central role in Iran’s strategy and the Iranian authorities’ response to its setbacks, including Tehran’s strategic narrative, centered around anti-U.S. and anti-Israel ideology. The paper concludes with an assessment of prospects for the future of Iran’s regional strategy.

The Doctrine of Strategic Depth

Over the past two decades, the Iranian leadership has framed its growing regional power around the concept of strategic depth. This refers to Iran’s ability to project soft power as well as geopolitical and military influence beyond its borders. Ali Khamenei, Iran’s Supreme Leader since 1989, has long been a proponent of the strategy as a way to enhance Iran’s national security.3 Iran built its strategic depth on a loose network of sympathetic actors throughout the Middle East, ranging from Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon to Assad’s regime in Syria, Shiite militias in Iraq, and the Houthis in Yemen, collectively dubbed the Axis of Resistance. The Palestinian cause and a shared antagonism towards Israel and the United States have been central to the foundational narrative of this network.

Khamenei has been adamant that viable strategic depth is crucial to Iran’s long-term security. In 2019, he advised the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) military command:

Do not lose sight of the vast geography of the resistance; do not lose sight of this transnational perspective. We should not limit ourselves to our immediate region… This broad transnational vision, this extension of strategic depth, is sometimes more crucial than even the most pressing domestic concerns.4

The IRGC’s Quds Force has been the central driver of this strategy. It has been responsible for developing, sustaining, and expanding the Axis of Resistance through military training, financing, arms supplies, and intelligence sharing. The Quds Force is the IRGC’s external operations branch, and occupies a special place in Iran’s relations with its neighbors. It has been designated by the United States as a terrorist organization since 2019.5 In subsequent years, Washington also sanctioned a number of commercial entities and individuals for facilitating the transfer of funds from the Quds Force to Hezbollah and Yemen’s Houthis.6

The Quds Force has played a crucial role in providing military support to Hezbollah and various other militias in the region, reportedly complemented by a network of registered charities that facilitate money transfers.7 This has won it public praise from Hezbollah leaders, who have publicly thanked the Force and its late Commander Qassem Soleimani for helping Hezbollah defeat Israel’s 2006 incursion into Lebanon.8 General Soleimani, widely credited for the success of Quds Force-led operations, was subsequently assassinated by a U.S. drone in January 2020 along with Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, then deputy commander of Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF).

That same month, the Force received high praise from Supreme Leader Khamenei, in a speech commemorating the death of General Soleimani. In Khamenei’s words, the Quds Force is made up of “fighters without borders” able to pre-emptively tackle extraterritorial threats to Iran.9

While the Quds Force operates in the shadows, its influence on Iran’s regional relations is widely acknowledged. A leaked 2021 audio recording of former foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif revealed that role. Zarif complained that the Foreign Ministry’s diplomatic activities were typically sidelined by the operational priorities of the Quds Force, even lamenting that the Force systematically torpedoed his attempts at diplomacy to de-escalate with the United States.10 The appointment of Iranian ambassadors in the Middle East has also reportedly been contingent on the Quds Force’s approval.11

Hezbollah in Action

Prior to October 7, 2023, Hezbollah was a central pillar of Iran’s strategic depth, carrying out operations against Israel in line with Tehran’s strategic interests. General Soleimani described Hezbollah as having gone beyond mere deterrence, demonstrating an ability to “bury the Israeli army with its missiles.”12 The group’s missile stockpile, designed to give it an advantage over Israel, was largely attributed to Soleimani.13 Iran had high hopes for Hezbollah, whose geographic proximity with Israel, disciplined fighters, and well-stocked arsenal were supposed to offer Iran significant leverage in times of crisis. Hezbollah had already proven its resilience against Israel in 2006, as well as proving its mettle and gaining battle experience in Syria. As far as Tehran was concerned, Hezbollah’s history and battle-readiness positioned it as a serious challenger to Israel.

Soon after Israel attacked Gaza in October 2023, Hezbollah began launching sporadic volleys of rockets on Israeli positions. These initially targeted Israeli military posts in the territorially disputed Shebaa Farms and the Golan Heights.14 But faced with Israeli retaliation and the escalating war on Gaza, Hezbollah expanded to other targets. In February 2024, Hezbollah fired Katyusha rockets at the Israeli town of Kiryat Shmona.15 Hezbollah’s strategy was aimed at opening a new front that would force Israel to divide its forces between two different conflict theatres. While Hezbollah is widely thought not to have intended to engage in a full military conflict,16 it hoped that its tactic would be enough to alleviate the pressure on Gaza and ultimately force a ceasefire. This strategy aligned with those of the other members of the Axis of Resistance. The Houthis in Yemen responded to the war on Gaza by imposing a blockade on cargo ships destined for Israel via the Red Sea and firing occasional rockets and drones at Israel.

Hezbollah continued its retaliations against Israel into 2024. Nasrallah frequently vowed that Hezbollah’s attacks would persist as long as Israeli forces maintained their operations in Gaza.17 He also rejected calls for the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1701, which called on Hezbollah to retreat from the border to the north bank of the Litani River. In February 2024, Nasrallah said it would be “easier to move the Litani River forward to the border than push back Hezbollah fighters from the borders to the Litani River.”18

Throughout 2024, Israel conducted many sorties targeting munition stockpiles and arsenals of missiles in Lebanon, killing civilians in the process. Yet the dynamic of the conflict shifted dramatically in late 2024. In September, Israel triggered the pagers used by Hezbollah operatives to explode, inflicting widespread casualties and disrupting the group’s command chain.19 Just days later, Nasrallah himself was killed in an Israeli airstrike. His assassination was a devastating blow both to Hezbollah and Iran. It was followed by a wave of targeted killings to eradicate Hezbollah’s leadership, including his then potential successor, Hashem Safieddine.20 Concurrently, Israel launched a ground offensive into Lebanon. Hezbollah initially vowed to continue its attacks on Israel as long as the war on Gaza persisted, in line with Iran’s official stance.21 But with its military capacities seriously depleted, it finally accepted the ceasefire deal, agreeing to move its fighters north of the Litani River, and reneging on its commitment to fight as long as Israel continued its war on Gaza.22

Spinning Defeat: Iran’s Efforts to Salvage Hezbollah’s Reputation

While Hezbollah’s relationship with Iran is opaque, it is safe to assume that the ceasefire was linked to an Iranian decision to spare Hezbollah’s remaining forces from Israel’s relentless attacks, with a view to replenishing and rebuilding their capacities. Iran’s leadership has also sought to salvage what it could of the group’s reputation, weaving a narrative that rejected notions of the group’s weakness and defeat. Supreme Leader Khamenei set the tone in his condolence message in the wake of Nasrallah’s killing, stating:

The foundation [Nasrallah] established in Lebanon and the direction he provided to other centers of resistance will not only endure despite his absence, but will also gain greater strength through the blessing of his blood and the blood of other martyrs of this incident… He was not merely an individual; he was a path and a school of thought, and this path will continue to persist.23

This message was echoed by other officials. IRGC chief Major-General Hossein Salami argued that “when Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah and other commanders of the resistance front were martyred, Hezbollah became even stronger.”24 Iran also sought to cast the U.S.-brokered Israel-Lebanon ceasefire deal, which removed Hezbollah forces from the Israeli-Lebanese border region, in a positive light. Ali Mohammadi, Representative of the Supreme Leader in the Quds Force, claimed that Hezbollah forced Israel into a ceasefire by demonstrating the “power of resistance.”25

Support for Hezbollah transcends factional politics in Iran. Salami’s statement on Nasrallah’s death was echoed by reformists in Pezeshkian’s government, including Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi26 and Mohammad Javad Zarif, then Pezeshkian’s strategic foreign policy adviser. Zarif argued that Hezbollah’s fate is tied to that of Palestine: as long as Israel occupies Palestinian lands, Hezbollah must remain to challenge it.27 Such revolutionary messaging has been a constant pillar in Iran’s foreign policy since 1979, engrained in the Islamic Republic’s identity and unifying both hardliners and reformists. Optimistic official talk of the inevitable victory of the Axis of Resistance suggests that this ideological commitment persists. But such messaging is in stark contrast the reality on the ground in early 2025.

Obstacles to Hezbollah’s Resurgence

In 2006, Iran invested heavily to help Hezbollah recover from the war with Israel. In 2025, plans for the resurrection of Hezbollah face major obstacles. First, in 2006 Iran was reaping the benefits of rising oil prices, giving Tehran significant scope for largess towards Hezbollah. Nasrallah publicly acknowledged this support:

The budget of Hezbollah, its salaries, its expenses, its food, its drink, its weapons, and its missiles come from the Islamic Republic of Iran… As long as Iran has money, we will have money.28

Today, Iran’s economy is much weaker. In October 2024, Iran’s Minister of Economic Affairs and Finance Abdolnasser Hemmati announced that Iran was grappling with a budget deficit of approximately $8 billion for that year.29 By March 2025, the economy was in such a dire state that Hemmati was impeached.30 This underlines major economic challenges for Iran, with far-reaching social and political ramifications. Major nationwide protests have repeatedly rocked the regime; neglecting the domestic economy in order to divert resources to Hezbollah would likely spark further unrest.

Second, Hezbollah has suffered major losses in its leadership. Unlike in 2006, Israel has eliminated nearly all of Hezbollah’s key military commanders. These losses have undermined Hezbollah’s organizational cohesion and strategic effectiveness. Without influential and charismatic leaders, Hezbollah’s Road to recovery will be challenging. It is noteworthy that the group’s current Secretary General Naim Qassem has allegedly been forced to move to Iran for fear of being assassinated,31 further weakening his leadership.

Third, Syria can no longer serve as the transit corridor and logistical hub for the shipment of arms from Iran to Hezbollah in Lebanon. The dramatic collapse of Assad’s rule has broken Syria’s land connection with Hezbollah, a link Iranian officials have often acknowledged as vital to the Axis of Resistance. Fourth, Israel has learned from its experience in 2006, when it allowed Hezbollah to regroup and rearm after Israeli forces withdrew from Lebanon. The current ceasefire agreement indirectly bars Hezbollah from rearming.32 Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has emphasized that “If Hezbollah violates the agreement and tries to rearm, we will attack. If it tries to rebuild terror infrastructure near the border, we will attack.”33

Fifth, broader international and regional developments are likely to exert additional pressure on both Iran and Hezbollah. The return of Donald Trump to the White House, with his strategy of maximum pressure on Iran, is already adding to the strains on the Iranian economy—notwithstanding his announcement in March 2025 that he wanted to negotiate a nuclear deal with Iran, and had written to its leadership to propose a new round of negotiations.34 Khamenei quickly responded that Tehran would not be bullied into talks.35

In Lebanon, intensified U.S. pressure has already brought to power a coalition with the stated aims of preventing Hezbollah from rearming, and asserting the sovereignty of the state. In January 2025, Lebanese lawmakers elected army chief Joseph Aoun as Lebanon’s president, filling the post after a two-year political deadlock. Aoun has declared that the Lebanese army is solely responsible for national security.36Taken together, these factors strongly suggest that Hezbollah is unlikely to recover in the short term.

Conclusion

Iran has invested heavily in the Axis of Resistance, seeing it as a vital tool for gaining strategic depth in the Middle East. The IRGC’s Quds Force has played a central role in cultivating and supporting allied militia groups across the region, building on the template of Hezbollah, which has remained a vital node in this strategy. Iran’s systematic application of an ideological prism in its regional and global power projection also made the Axis indispensable to Tehran. However, developments in the final months of 2024 presented it with unprecedented challenges, reducing the fighting capacity of Hezbollah and the cohesion of the Axis of Resistance.

Today, Hezbollah’s leadership has been eliminated, its arsenal of missiles seriously depleted, and its fighters forced to withdraw north of the Litani River. Iran has limited resources to invest in Hezbollah’s recovery, and has lost its land corridor to Lebanon through Syria. Regional and global dynamics have also seriously undermined Iran’s position. Israel has explicitly stated that it will not allow Hezbollah to rearm, and President Trump has again ratcheted up the pressure on Iran, depriving it of the resources necessary to replenish Hezbollah.

The Iranian leadership, however, appears committed to its strategy of gaining strategic depth by supporting armed groups across the Middle East. This strategy poses obvious hurdles to Iran’s relations with its neighbors and the United States. Expectations that the new Pezeshkian government will manage to revive the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) are fast dissipating as it cements the familiar narrative of resistance to the United States, now under the uncompromising administration of President Donald Trump.

Endnotes

1 AFP, “Sayyed Nasrallah: Difficult Reckoning Awaits ‘Israel’, Hezbollah Won’t Stop Pro-Gaza Front,” Al-Manar, September 21, 2024, https://english.almanar.com.lb/2202466.

2 Linda Gradstein, “Ceasefire deal: Hezbollah to move north, Israeli troops to gradually withdraw,” Voice of America, November 26, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/ceasefire-deal-hezbollah-to-move-north-of-litani-river-israeli-troops-to-gradually-withdraw/7877957.html.

3 “Strategic depths of the Islamic Republic,” Ali Khamenei’s official website, July 31, 2020, accessed March 8, 2025 (in Farsi), https://farsi.khamenei.ir/newspart-index?tid=1034.

4 “Statements at the Supreme Assembly of IRGC Commanders,” Ali Khamenei’s official website, October 2, 2019, accessed March 8, 2025 (in Farsi), https://farsi.khamenei.ir/speech-content?id=43632.

5 “Country Reports on Terrorism 2019,” U.S. State Department, Bureau of Counterterrorism, accessed March 8, 2025, https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2019/iran/.

6 “Treasury Targets Qods Force, Houthi, and Hizballah Finance and Trade Facilitators,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, March 26, 2024, accessed March 8, 2025, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2209.

7 Yuriy Matsarsky, “Enriched Iranium: How ayatollahs fund Hamas, Houthis, and Hezbollah,” The Insider, January 12, 2024, https://theins.ru/en/society/268270.

8 “Sheikh Naim Qasem’s explanation of General Soleimani’s direct presence in the War,” ISNA, 7 July, 2020 (in Farsi), https://www.isna.ir/amp/99041713080/.

9 “New Points of Friday Prayer Sermons on January 17,” Mashregh News, January 21, 2020 (in Farsi), https://www.mashreghnews.ir/news/1033604.

10 “Zarif’s audio file: Qassem Soleimani was an obstacle to diplomacy,” Radio Farda, May 5, 2021 (in Farsi), https://www.radiofarda.com/a/iran-zarif-qassem-soleimani-attack/31222159.html.

11 Shahir Shahid Sales, “Photographs that revealed ‘a real flaw’ in the Iranian government,” BBC Persian, February 28, 2019 (in Farsi), https://www.bbc.com/persian/iran-features-47405529.

12 “Unpublished Speech by Haj Qassem Soleimani: Hezbollah Could Bury the Israeli Army,” Tasnim News Agency, December 10, 2019 (in Farsi), https://tn.ai/2421105.

13 “Senior Lebanese Hizbullah Official: Haj Qassem Came Up with the Idea of “Israel’s Missile Blockade,” Tasnim News Agency, January 25, 2021 (in Farsi), https://tn.ai/2837566.

14 Tia Goldenberg and Wafaa Shurafa, “Israel declares war, bombards Gaza and battles to dislodge Hamas fighters after surprise attack,” Associated Press, October 9, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/israel-palestinians-gaza-hamas-rockets-airstrikes-tel-aviv-ca7903976387cfc1e1011ce9ea805a71.

15 Mohammed Zaatari and Bassem Mroue, “Israeli airstrikes killed 10 Lebanese civilians in a single day. Hezbollah has vowed to retaliate,” Associated Press, February 15, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/lebanon-israel-airstrike-nabatiyeh-294288635bb489fdefd8d36978651554.

16 Jane Arraf and Scott Simon, “Hezbollah spokesperson says the group doesn’t want an all-out war in the region,” NPR, July 11, 2024, https://www.npr.org/2024/07/11/nx-s1-5036559/hezbollah-spokesperson-says-the-group-doesnt-want-an-all-out-war-in-the-region.

17 “Hezbollah chief says only Gaza ceasefire will end Lebanon border attacks,” Al Jazeera, February 13, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/13/hezbollah-chief-says-only-gaza-ceasefire-will-end-lebanon-border-attacks.

18 “Sayyed Nasrallah: It is easier to move Litani River forward to the borders than pushing back Hezbollah fighters from the borders to the Litani River,” Al-Manar, February 13, 2024, https://english.almanar.com.lb/2044737.

19 Matt Murphy and Joe Tidy, “What we know about the Hezbollah device explosions,” BBC News, September 20, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cz04m913m49o.

20 Kareem Chehayeb and Jack Jeffery, “Who were the 7 high-ranking Hezbollah officials killed over the past week?,” Associated Press, September 30, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/hezbollah-lebanon-nasrallah-israel-8b2ae56a54d641c6910a79e9e5699824.

21 “Hezbollah Fighters Pledge Loyalty to Sayyed Nasrallah in a Heartfelt Message,” Al-Manar, October 1, 2024, https://english.almanar.com.lb/2215545.

22 Emanuel Fabian and Lazar Berman, “PM said meeting on Lebanon diplomatic solution; Hezbollah has lost 80% of its rockets,” Times of Israel, October 29, 2024, https://www.timesofisrael.com/pm-said-meeting-on-lebanon-diplomatic-solution-hezbollah-has-lost-80-of-its-rockets/; Murphy and Tidy, “What we know.”

23 “Message of condolences on the martyrdom of Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah Secretary General of the Lebanese Hezbollah,” Ali Khamenei’s official website, September 29, 2024, accessed March 8, 2025 (in Farsi), https://farsi.khamenei.ir/message-content?id=57700.

24 “Maj. Gen. Salami: Hezbullah has become stronger,” Asr-e Iran, November 29, 2024, https://www.asriran.com/004Gh8.

25 “IRGC Quds Force Official’s Message to Lebanese Hezbullah Secretary-General,” Khabar Online, November 30, 2024, https://www.khabaronline.ir/news/1990140.

26 “Belief in the Resistance and Hezbollah: A School of Thought That Continues Unceasingly,” YJC, October 4, 2024, https://www.yjc.ir/00b4Lx.

27 “Zarif: Hezbollah is alive,” Iranian Diplomacy, November 10, 2024, http://www.irdiplomacy.ir/fa/news/2029277.

28 “Hassan Nasrallah: Hizbullah’s Money and Missiles Reach Us Directly from Iran, No Law Will Prevent This,” MEMRI TV, June 24, 2018, https://www.memri.org/tv/hassan-nasrallah-hizbullahs-money-and-missiles-reach-us-directly-iran-no-law-will-prevent.

29 “5 scenarios for deficit compensation,” Donay-e Eqtesad, October 17, 2024, https://donya-e-eqtesad.com/fa/tiny/news-4114014.

30 “Iran’s economy minister impeached as inflation rises, currency falls,” Al Jazeera, March 2, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/3/2/irans-economy-minister-impeached-amid-rising-inflation-falling-currency.

31 Jacqueline Howard, “Hezbollah announces Naim Qassem as new leader,” BBC News, October 29, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c89vx50g4l5o.

32 What we know about Israel-Hezbollah Ceasefire Deal,” BBC, November 27, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cx2d3gj9ewxo.

33 Gradstein, “Ceasefire deal.”

34 Doina Chiacu, “Trump says he sent letter to Iran leader to negotiate nuclear deal,” Reuters, March 8, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/trump-says-he-sent-letter-iran-leader-negotiate-nuclear-deal-2025-03-07/.

35 Parisa Hafezi, “Iran will not negotiate under U.S. ‘bullying’, Supreme Leader says,”Reuters, March 9, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/irans-khamenei-says-tehran-will-not-negotiate-under-us-bully-pressure-2025-03-08/.

36 Hussain Abdul-Hussain, “Lebanon’s Aoun could move toward peace – if Hezbollah lets him,” Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, January 10, 2025, https://www.fdd.org/analysis/2025/01/10/lebanons-aoun-could-move-toward-peace-if-hezbollah-lets-him/.