Division and Disaster:

Libya’s Political Fragmentation and Response to the Derna Flood

Issue Brief, August 2024

Key Takeaways

Political, security, and institutional divisions exacerbated Derna’s flood damage: Post-2011 political and security divides worsened the flood’s damage in the Libyan city of Derna. Various authorities failed to allocate sufficient funds for the maintenance of dams, implement proper security measures to encourage the return of foreign maintenance companies, and coordinate national and international reconstruction efforts.

The disaster showed that regional divisions can be temporarily set aside in the face of a national crisis: The large-scale national response to the Derna flood demonstrated that Libyans’ desire for national unity can occasionally transcend regional and societal divisions. However, such moments of unity are temporary as ruling authorities in the country’s east and west continue to exploit these divisions to maintain the status quo.

Regional rapprochement provided an opportunity to reassess issue-based local cooperation despite rivalries: The flood prompted the authorities in both eastern and western Libya to coordinate relief efforts with regional countries supporting their rivals. This suggests that, in a context of a rapprochement between regional rivals involved in the Libyan conflict, limited, issue-based cooperation between otherwise opposing actors is sometimes possible.

Politics is overshadowing reconstruction efforts: Parties competing for power in Libya are politicizing disaster response and reconstruction efforts in Derna to bolster their political influence and advance their personal interests. They do so by controlling the mechanisms for implementing contracts with foreign companies interested in Derna’s reconstruction.

Introduction

A devastating flood hit the Libyan city of Derna on September 10 and 11, 2023. It resulted from the collapse of two dams after heavy rainfall pounded the eastern coastline of Libya due to Storm Daniel’s passage through the Mediterranean.1 The disaster obliterated a quarter of Derna and inflicted severe damage to areas near the cities of Sousa, Shahat, Al-Marj, and Al-Bayda. The floodwaters swept numerous residents, entire neighborhoods of buildings, and bridges into the sea.

A report from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) on March 20, 2024, estimated the death toll at 5,923.2 About 22% of Libya’s population resides in the flood-affected areas, with approximately 250,000 people impacted and 45,000 displaced.3 According to a report prepared by the World Bank, the United Nations, and the European Union, the flood incurred damages and losses estimated at $1.65 billion, with reconstruction and recovery needs amounting to $1.8 billion.4

The Derna tragedy was both natural and man-made. Although the city previously experienced floods in 1942, 1959, 1968, and 1986, the devastating effects of the 2023 flood can only be partially attributed to the rainfall.5 In the case of Derna, political and security divisions, as well as the fragility of Libya’s governance institutions, all contributed significantly to the flood-related destruction. The political reality of Libya is marked by division, chaos, and corruption.6 This caused clashes between local and international mobilization efforts to deliver aid and relief to those impacted.

Furthermore, the high levels of corruption in Libya, including government spending policies aimed at securing political loyalty, raise concerns about the transparency of the reconstruction process in Derna. This is particularly troubling given the tendency of influential politicians in both the east and west of the country to dominate reconstruction projects. These projects will constitute a major part of the Libyan state budget, which is otherwise heavily reliant on hydrocarbons; oil and gas make up “97% of exports, more than 90% of fiscal revenues, and 68% of GDP.”7

This issue brief discusses the impact of institutional divisions on the Libyan state’s response to the Derna flood disaster. It also explores the politicization of relief and reconstruction efforts and their implications for the political future of Libya.

Post-2011 Political and Institutional Divisions

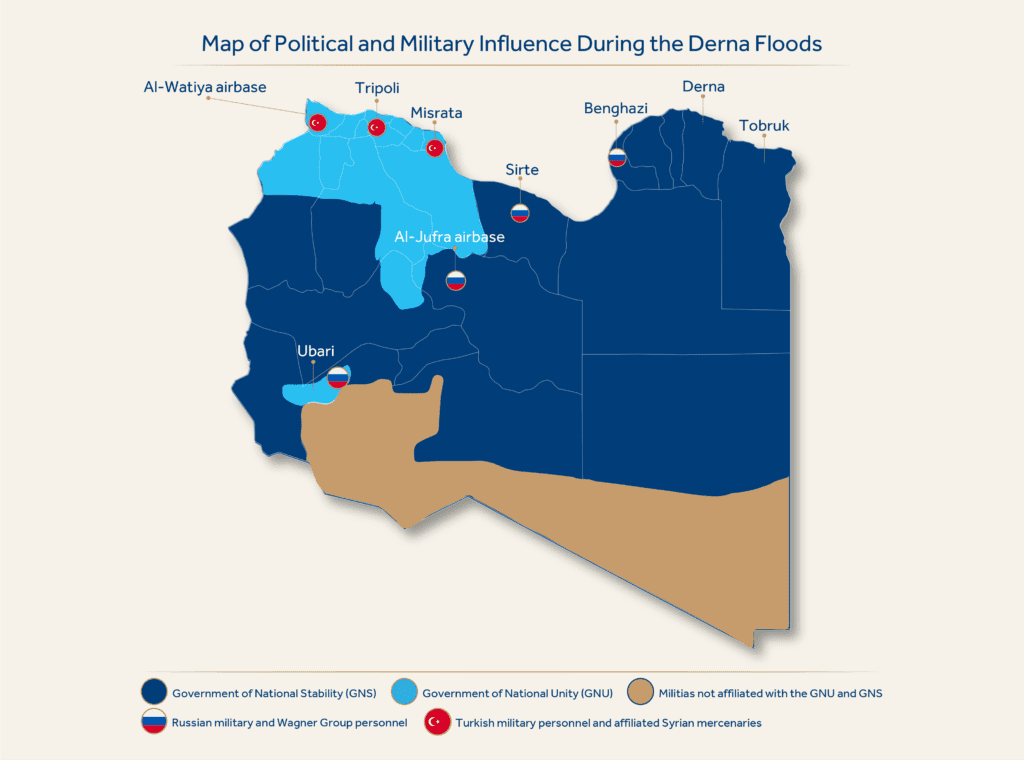

Since 2014, Libya has suffered from a significant legitimacy crisis resulting from political and institutional divisions. Two governments with distinct political and military alliances rule the country. The western Government of National Unity (GNU) is based in Tripoli, while the eastern Government of National Stability (GNS)—backed by the House of Representatives (HoR)—is located in Benghazi (formerly in Tobruk). These divisions extend to the country’s key economic institutions, such as the Central Bank of Libya (CBL), National Oil Corporation, and Libyan Investment Authority, and have contributed to deteriorating living circumstances and entrenched corruption.8

When the Derna flood occurred, the internationally recognized GNU controlled Tripoli via four main armed groups: the Stabilization Support Apparatus, Deterrence Apparatus,9 General Security Service, and the 444th Brigade. Outside of Tripoli, armed groups in Jabal Nafusa, Al-Zawiya, Zintan, and Misrata are formally associated with the GNU but operate independently, as the GNU’s ability to govern outside the capital remains limited.

Military commander Khalifa Haftar leads the Libyan Arab Armed Forces (LAAF)—a cluster of paramilitary units that control the eastern region where Derna is located. This area includes the country’s largest oil fields and the central cities of Sirte and Jufra. The LAAF also has significant influence in some parts of southern Libya. . Haftar’s sons, Brigadier Generals Khaled Haftar and Saddam Haftar, serve as the chiefs of staff of the LAAF’s security and land forces, respectively,10 leading the largest military units upon which their father and his political allies in the HoR and GNS rely.

The institutional and political divisions reflect Libya’s fragmented security structure following the fall of the regime of the late Libyan leader Muammar Gadhafi. Under this structure, numerous armed groups with various affiliations and alliances exercise control over political decisions.11 Each faction is supported by rival political leaders and regional powers. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt, and Russia back Haftar and his allies, while Türkiye, Qatar, and Italy support groups in the west.12 In addition, there are thousands of foreign fighters—including Türkiye-affiliated Syrian mercenaries, those from the Wagner Group,13 and Turkish military personnel14—stationed in various places within Libya.

Figure 1: The Areas of Political and Military Influence in Libya at the Time of the Derna Flood Disaster

Source: Liveuamap (July 2024) and Aude Thomas (2020).15

Pre-Flood Failures and Immediate Response

Two fundamental governance problems exacerbated the catastrophic failure of the Derna dams. The first is the historical neglect of the maintenance of the city’s two largest dams, the Wadi Derna and Abu Mansour dams, built by a Yugoslav company in the 1970s.16 A Swiss company confirmed the presence of major fractures in 2003 and suggested building a new, third dam after repairing the flaws in the current dams; this was never done.17

Five years after the fractures were discovered, the Libyan government contracted a Turkish company, Arsel Construction, to maintain the dams.18 However, due to financial delays, work on the dams did not begin until 2010 and was never completed.19 Arsel claimed on its official (now defunct) website that it completed the project in 2012.20 However, official Libyan sources confirmed that the company did not finish work21 before leaving the country after gunmen looted its sites during the 2011 uprising.22

The Libyan Audit Bureau’s 2021 report stated that former Prime Minister Ali Zaidan’s administration spent over $2 million on dam maintenance in 2012 and 2013.23 However, owing to the deteriorating security situation in Libya, particularly in Derna, no construction was completed. The city, which was neglected throughout the Gadhafi period due to its status as an opposition stronghold, fell under the influence of local and foreign jihadist groups after 2011.24 It was seized by Haftar’s forces in 2018, following fierce fights that caused more damage to its infrastructure.25

Although the GNU budgeted over $335 million in 2021 for the reconstruction of Benghazi and Derna,26 much of the money was not utilized for fear that it would slip into the hands of Haftar. The CBL, based in Tripoli, processes all hard currency transactions in both eastern and western Libya, and can prevent ministries, municipalities, and urban development agencies from purchasing building supplies directly or working with international contractors and consulting firms. The GNU feared that Haftar might use this fact to deflect blame for the disaster onto officials in Tripoli, particularly at the CBL.27 Furthermore, Haftar’s prior threats against Turkish interests in Libya,28 which stemmed from Ankara’s support for political and military forces in the capital, likely prevented Arsel from returning to Derna.

The second governance issue stems from inadequate preventative measures that were a result of oversights at the Libyan Meteorological Authority (LMA). According to Petteri Taalas, Secretary-General of the World Meteorological Authority, the LMA’s lack of adequate financing prevented it from issuing effective warnings regarding the flood.29 The LMA issued storm warnings in Derna30 but did not warn of any potential dam failure. The authorities ignored the danger even after a report by a scientist at Omar Al-Mukhtar University clearly identified flooding risks as early as 2022.31 During predicted severe rains, dam operators usually collaborate closely with meteorologists to progressively release water, preventing hydraulic pressure from exceeding the dam’s operating capacity. However, this critical step was overlooked in Derna.32

Furthermore, in the areas swept away by the flood, conflicting instructions and a general lack of trust in the authorities controlling the city left civilians confused and insufficiently prepared to evacuate. For example, while residents were initially told to evacuate some areas of the city, the Derna security director asked residents to stay in their homes and abide by a two-day curfew.33

Confusion also impeded the evacuation procedures, as the authorities failed to specify safe locations where residents should take shelter. Focusing on the wrong parts of the city, they urged evacuation from areas facing the sea, believing that the storm surge was the primary concern.34 As such, many citizens headed to the city center where they were then submerged by the floodwaters.35

National and International Mobilization Efforts

The immediate humanitarian reaction to the floods was robust. According to OCHA, 26 foreign partners assisted almost 250,000 individuals by January 2024.36 Furthermore, 800 search-and-rescue personnel from a dozen countries assisted local first responders.37 Both official and civil society responses coordinated international relief teams to facilitate aid delivery, search for missing persons, distribute compensation funds, and complete other related tasks.

Initially, there were concerns that political disputes and rivalries between regional powers involved in Libya would hamper relief operations, possibly leaving Derna without vital assistance. Instead, international aid to Derna entered through airports and seaports controlled by entities affiliated with both the eastern and western authorities.38 The rapid arrival of volunteers, rescue teams, and assistance convoys from around Libya to the flooded areas sparked hope for a moment of national unity.39 As such, the disaster response signaled a limited, temporary victory for a unified national identity over regional and tribal divisions, which are frequently cited as contributing factors to Libya’s ongoing political and social fragmentation.

Moreover, many civil society efforts to aid Derna involved collaboration between local authorities and foreign organizations, including UN agencies and the Libyan International Non-Governmental Organization (INGO) Forum.40 Optimism about achieving national unity peaked when a militia that had previously fought against Haftar’s forces during the campaign to seize Tripoli collaborated with them on rescue efforts.41

The Derna disaster provided a new opportunity for short-term cooperation between eastern and western Libyan ruling authorities and their regional backers. International humanitarian operations temporarily broke down the usual geopolitical barriers. As expected, Haftar’s allies, the UAE and Egypt, stepped in to help.42 More surprisingly, states backing anti-Haftar factions in western Libya also acted swiftly; Türkiye and Italy promptly dispatched search and rescue teams to Derna, followed by ships carrying equipment and medical supplies.43

In the context of Ankara’s ongoing rapprochement with Haftar’s main external backers, Egypt and the UAE,44 Türkiye’s humanitarian involvement in Derna is particularly noteworthy. Just a year before the floods, it would have been unthinkable to see a Turkish naval ship off the coast of eastern Libya, let alone Turkish personnel on the ground there. However, in a radical shift, the warming relations between these regional powers enabled the Turkish Ambassador to Libya Kenan Yilmaz to visit Derna, accompanied by HoR Prime Minister Osama Hammad.45 During the visit, Ankara emphasized the readiness of Turkish companies to contribute to the reconstruction of Derna.46 Despite intervening militarily three years before the flood to prevent Haftar’s advance toward Tripoli, Türkiye is expanding its involvement in eastern Libya, cultivating political and commercial relationships.47 Meanwhile, Qatar, which had supported Tripoli throughout Haftar’s invasion, also came to Derna’s aid.48

The Impact of Political and Institutional Divisions on Reconstruction Efforts

Despite the aforementioned successes of the humanitarian response to the flood, local and international mobilization efforts also collided with the fragmented local political interests. Derna residents protested governmental neglect and corruption, burning the house of the former mayor of Derna and demanding an international trial for those responsible for the disaster.49 In response to the protests, authorities in eastern Libya suspended the city’s internet and telephone access, expelled journalists, and delayed and obstructed humanitarian access to the affected sites.50

Libyan Attorney General Al-Siddiq Al-Sour, who is based in Tripoli but not officially linked to the GNU or the GNS, subsequently opened an investigation.51 He prosecuted 16 officials, including two Derna Municipal Council members, the director of the city’s reconstruction projects office, and the head of the technical committee tasked with implementing the city’s reconstruction projects.52 The accusations also targeted Ali Al-Hibri, the head of the Committee for Reconstruction and Stabilization of Old Benghazi and Derna, who is also the former deputy governor of the parallel central bank.53

However, Libya’s political and institutional divisions make it difficult for the judiciary to prosecute well-connected officials who may be responsible for the disaster. Al-Sour effectively targeted officials from local government councils and institutions with weak links to the ruling authorities. However, the probe is unlikely to result in true accountability for Libya’s senior executive and legislative leaders, as powerful political actors continue to maintain control over the judiciary and law enforcement bodies. Al-Sour himself was appointed as attorney general through an agreement between the High Council of State in Tripoli and the HoR in Benghazi in April 2021.54

Al-Sour’s investigation is expected to become another source of political conflict between the two rival governments. Already the High Council of State has urged for international involvement in the probe,55 aiming in part to pressure the Haftar camp to explain its refusal to appoint new contractors to maintain the two dams. Yet, accountability for the dam disaster was not Tripoli’s main objective in seeking foreign engagement; the primary goal was to drive the GNS and Haftar to make political concessions.

Given this context, it is unsurprising that political division has hampered reconstruction efforts, with rival authorities attempting to use reconstruction initiatives for political and financial benefits. For instance, the GNS—which is not internationally recognized—requested the international community’s participation in a reconstruction conference.56 This was later delayed to provide corporations with “the necessary time to present effective studies and projects that will contribute to the reconstruction process.”57 On the other side, the internationally recognized GNU in Tripoli requested funds from the World Bank.58 These efforts lacked coordination and processes to find consensus between the two competing administrations, which would have helped to structure the reconstruction fund and ensure transparency. As the United Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) emphasized, it is crucial to create a unified national mechanism to drive and coordinate reconstruction activities.59

Meanwhile, the process of reconstruction is also expected to pique the interest of GNU Prime Minister Abdul-Hamid Dbeibah—a construction mogul turned politician.60 Corruption allegations against his government have raised concerns about its role in reconstruction.61 The Derna and Benghazi Reconstruction Fund, established by Dbeibah’s government in 2021,62 has so far failed to help the city recover from the damage it sustained in 2018. Furthermore, the Tripoli authorities’ participation in the reconstruction of Derna is likely to prove challenging without the approval of Haftar and his inner circle, who will likely hinder this participation without lucrative benefits for themselves.

On the other side, Haftar is using the Derna flood to garner more political clout and consolidate his position. It was apparent from the start that the Haftar family was using the humanitarian crisis to consolidate control over eastern Libya and dictate the country’s political future. Notably, Saddam Haftar assumed leadership of the city’s Disaster Response Committee,63 and one of his brothers was appointed chairman of the Development and Reconstruction Fund for Derna and the Affected Areas.64

While “flood diplomacy” provided an opportunity for short-term cooperation between the Libyan ruling authorities in the east and west and some of their rivals from regional states, pragmatic alliances remain dominant. Eastern Libyan authorities are again favoring their regional allies, awarding a major portion of reconstruction contracts to Emirati and Egyptian companies.65 Similarly, GNU ally Türkiye is prepared to participate significantly in the reconstruction of Derna, particularly after positive signals from the CBL in Tripoli.66

The Implications of Politicizing the Derna Flood Disaster

The Derna tragedy adds another terrible chapter to Libya’s continuous turmoil since 2011, which has divided the country into antagonistic governments vying for power and money. This prolonged political and institutional division has undermined government institutions, weakened the rule of law, and caused great suffering among Libyans. By late 2020, the conflict had cost the Libyan people more than $576 billion,67 with most of this sum spent on the military and corrupt deals rather than development, healthcare, education, and key infrastructure.

The rentier structure of the Libyan economy, which persisted even in the post-Gadhafi period, facilitated the ruling authorities’ ability to buy political loyalty and inflated government expenditure. This undermined the possibility of independent, private-sector participation in reconstruction projects, exacerbating Libya’s vulnerability to the effects of climate change and impeding disaster response efforts.

Notably, local mobilization efforts to ameliorate the effects of the Derna floods revealed Libyan society’s resolve to overcome regional and political divisions, as seen by local mobilization and coordination efforts. In parallel, the ongoing regional rapprochement provided an opportunity for external powers to pursue shared economic and humanitarian interests in Libya. Two examples of this are Türkiye’s openness towards Libya’s eastern authorities and the Western authorities’ acceptance of aid from its rivals’ regional backers. These slight shifts in regional attitudes towards Libya, and in Libyan authorities’ views toward regional powers, will be more durable if they receive the support of neutral international actors, such as the United Nations, the European Union, and the African Union.

However, the Derna flood has also become yet another source of disputes between the two competing authorities over responsibility for negligence and mismanagement. As such, concerns are currently being raised about the politicization of reconstruction efforts, which further stall the rebuilding process. Haftar and Dbeibeh have pushed the committees responsible for coordinating reconstruction to allocate the majority of contracts to companies from regional countries that provide the leaders with political and military support (Emirati and Egyptian companies in the case of Haftar; Turkish ones for Dbeibeh).

Furthermore, more attention needs to be paid to the environmental issues facing the countries of the region in general and Libya in particular. It is beyond the capabilities of the Libyan authorities and citizens to overcome these difficulties alone; confronting them will require further international cooperation. Climate change has added complex new elements to Libya’s political landscape. Rising temperatures in North Africa will increase the frequency and severity of droughts and desertification, while rising sea levels and extreme weather events will intensify floods in coastal areas.68 This will continue to harm agriculture, exacerbate food shortages, and strain Libya’s already fragile infrastructure. The fragility of the current Libyan state, compounded by the challenges of climate change, could have consequences beyond Libya’s borders, exacerbating problems such as illegal immigration to Europe. Surmounting these difficulties will not be possible without greater international and regional cooperation, which should focus on addressing governance, economic, and security issues both in Libya and its neighboring states.

Conclusion

The consequences of the Derna flood have highlighted the severity of Libya’s governance crisis. In addition to historical and structural issues, the continuation of armed conflict and political and security divisions since 2011 have further undermined the Libyan state’s capacity for disaster response. Strengthening the country’s capabilities to confront environmental challenges demands a comprehensive approach to rebuilding effective state institutions and resolving Libya’s political, security, and economic dilemmas. This approach should prioritize coordination between local and international stakeholders to mitigate the politicization of reconstruction efforts and ensure their success independent of short-sighted, personal interests.