Russia in the Mediterranean After Assad’s Fall

February 2025

Introduction

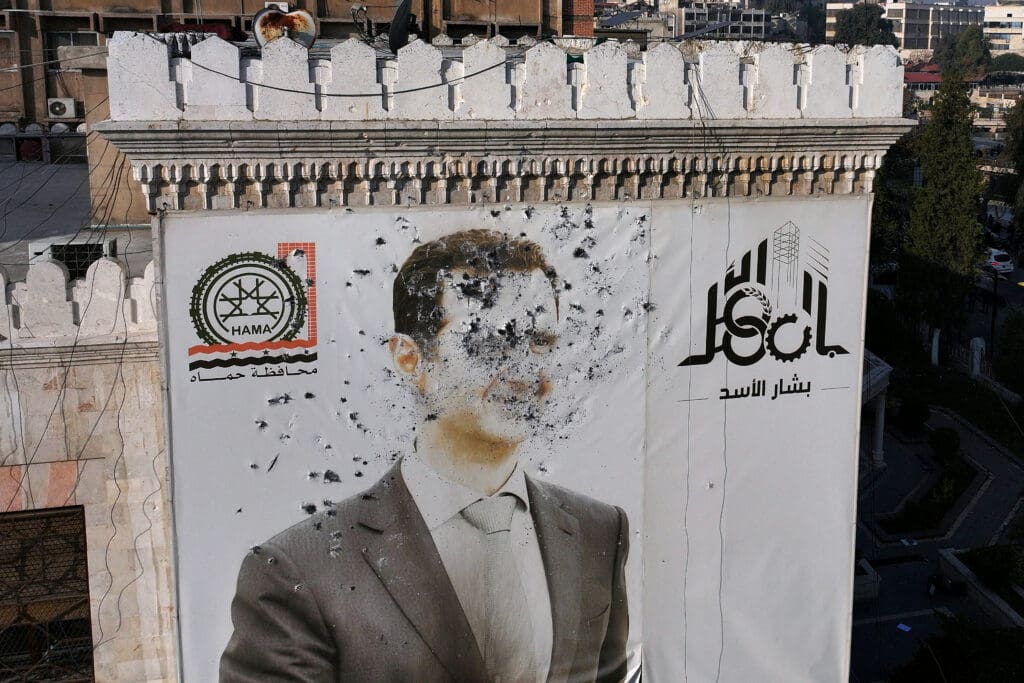

Had regime change happened in Syria in December 2021, instead of December 2024, it would have probably led to a broad and emotional public discussion about “who lost Syria.” Russia’s overall engagement in Syria and the wider Middle East region today has been completely overshadowed by the Russian-Ukrainian conflict—which remains not only a priority, but rather the priority of the country’s leadership. Therefore, the general Russian public remained mostly indifferent to the fall of Bashar Assad, as far back as 2016,1 who was often regarded more as a liability to Russia rather than a valuable asset. Russian state media tried hard to stay neutral in their reporting from Syria during the downfall, putting all the blame on the Syrian political and military chiefs, while downplaying the likely negative impact of Syrian developments on Russia’s positions in the MENA region, and beyond. Many critically minded experts promptly stated they had predicted long ago a hard landing for the Assad regime and Russia’s positions in Syria.2

Did Moscow Really Try to Prevent Regime Change in Damascus?

All such post-factum statements notwithstanding, it appears that, like other non-regional actors, Russia was not prepared to witness a rapid, unstoppable, and irreversible collapse of the Bashar Assad regime in Damascus. After all, the Assad family ran the country for half a century, and Bashar Assad demonstrated remarkable political survivability under very challenging circumstances. It remains an open question when Kremlin strategists concluded that Moscow should no longer try to stop the opposition offensive and should instead let the unpopular and inefficient regime fall.

There are reasons to assume that Russia might have decided to accept regime change in Syria at a relatively early stage of the opposition forces’ offensive, and even indirectly assist a surprisingly smooth and bloodless political transition. Official Russian military reports imply Russian air support to the Assad regime continued until at least December 7, 2024, inflicting significant damage upon the advancing opposition units in the provinces of Idlib, Aleppo, and Hama.3 Sergey Lavrov, Russia’s Foreign Minister, speaking that same day at the 22nd Doha Forum, confirmed Moscow’s support to Bashar Assad and its firm condemnation of the opposition offensive.4 However, the real scale of Russia’s combat and intelligence assistance to Assad and Russian air force commitment to fighting against the opposition in early December remain unclear. Later, according to the New York Times, Iranian Brig. Gen. Behrouz Esbati accused Russia of misleading Iran by saying that Russian jets were bombing Syrian rebels when they were in fact dropping bombs on open fields.5 He also said that in 2024: “as Israel struck Iranian targets in Syria, Russia had ‘turned off radars,’ in effect facilitating these attacks.”6

This account of the alleged Russian reluctance to stand by its long-term ally in late November/early December 2024 was indirectly confirmed by Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan in his recent interview with TASS news agency, when he said that “there were some escalations after Aleppo was captured, I assume. Russia had the military capability to respond and could have used it – but decided not to. We stayed in close contact on this issue. I will be honest, Russia acted as a calculated player.”7 Fidan added: “Moscow ‘did not intervene during the fall of Damascus’ and ‘the revolutionary forces eventually ensured the secure withdrawal of Russian troops and did not attack their bases.’”8

Immediate Implications for Russia’s Positions in Syria

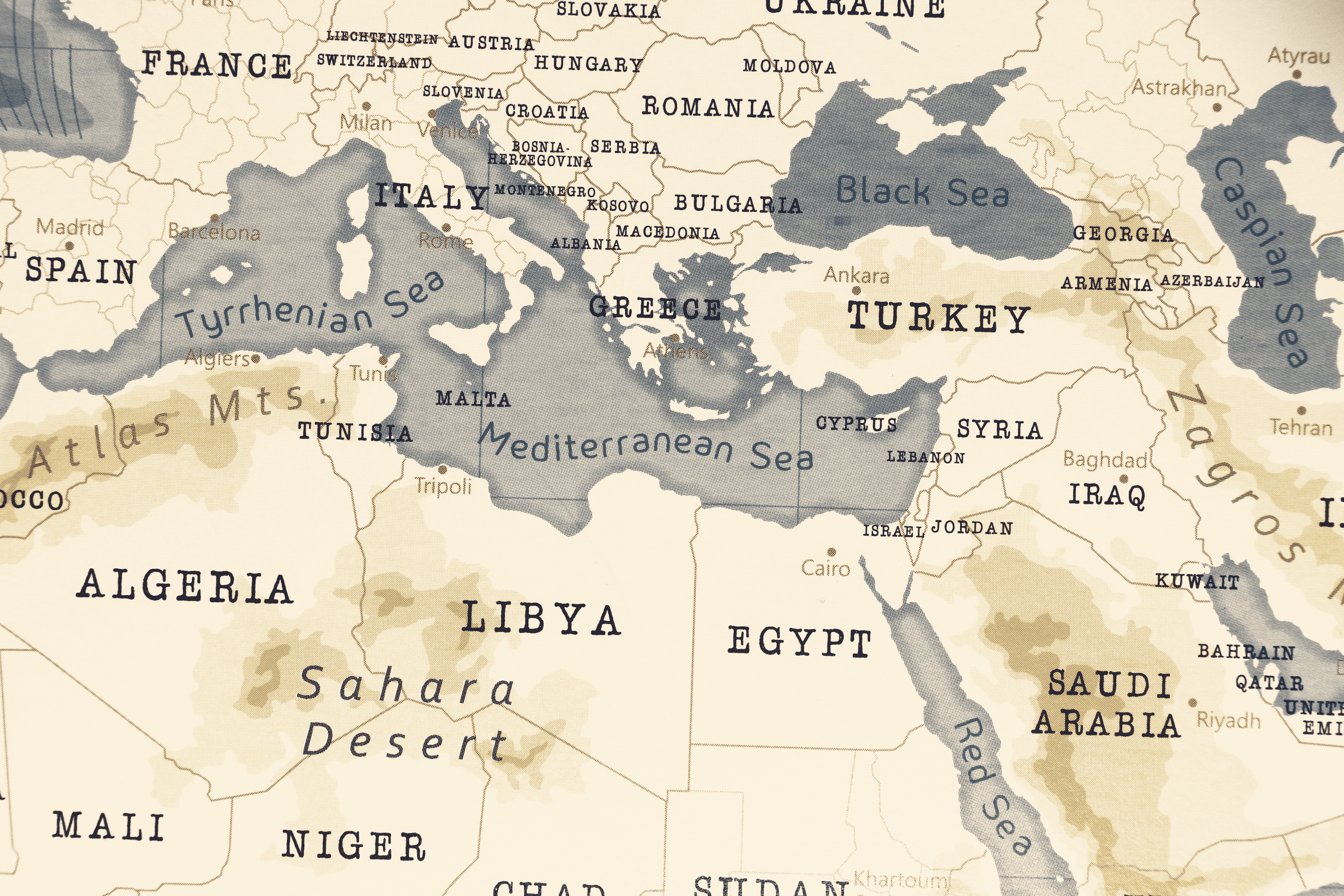

Today, Russia has two strategic points of military presence in Syria: the Tartous Naval Base and the Khmeimim Air Base. Tartous is Russia’s only naval facility in the Mediterranean. Established in the 1970s, it was significantly expanded and modernized since the beginning of the Russian military engagement in Syria. Khmeimim became operational in 2015 to assist Russia’s air operations during the Syrian civil war. These bases are essential for advancing Russia’s interests in the Mediterranean and in the broader Middle East, offering Moscow unique power projection capabilities in the region. Moreover, the bases (in particular, the Khmeimim air base) are used as critical transit points, serving Russia’s operations in remote places in Africa.9

Preserving these two bases has turned out to be one of the main goals of Russia’s post-Assad approach to Syria. In January 2025, the Russian Foreign Ministry even proposed that these bases could be converted into “humanitarian hubs” to assist the urgent needs of the Syrian population.10 It remains to be seen whether Russia is in a position to provide significant amounts of humanitarian assistance to Syria and to efficiently coordinate these efforts with other international donors.

The new Syrian administration seems to be skeptical of what Moscow can deliver in terms of humanitarian aid or development assistance. On a more general note, it would be hard to assume that Russia can easily win the trust of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) leaders who have been labeled by the Kremlin as international terrorists, close to al-Qaida and other extremist networks. Damascus has already canceled a contract with a Russian company to manage and operate the Tartous port that had been signed under former President Bashar Assad. Riad Joudy, the head of Tartous customs, is claimed to say that the investment contract was annulled after the Russian contractor failed to fulfil the terms of the 2019 deal, which included major investments into the port’s infrastructure.11 There were also media leaks suggesting that the Tartous port has attracted attention from major Turkish developers trying to control the port’s modernization. A more compelling reason for revising the old arrangement might have been EU diplomats exercising strong pressure on the new Syrian leaders, including a break with Moscow in their list of preconditions for intensive cooperation between Brussels and Damascus.12

However, the recent revision of Syria’s arrangement with Russia so far is limited to the civilian part of the Tartous port, and does not directly affect the status of the Tartous Naval Base, which Russia still intends to keep under its control.13 Syria’s transitional government leader Ahmed al-Sharaa stated that the new government had “‘strategic interests’ with the ‘second most powerful country in the world’” and that he “didn’t want Russia to exit Syria in a way that undermines its relationship with the country.”14 A high-level Russian delegation visited Damascus in January 2025 to discuss the future of bilateral relations with the new Syrian authorities. In a statement following the negotiations, the Syrian leadership stressed “that restoring relations must address past mistakes, respect the will of the Syrian people and serve their interests.”15 The talks also covered “justice for the victims of the brutal war waged by the Assad regime.”16 In sum, even if some level of Russia’s military presence in Syria is maintained, the terms of the presence are likely to change significantly, motivating Moscow to look for possible alternatives.

Likewise, the immediate prospects for Russia-Syria economic cooperation are dim at best. Bilateral trade once amounted to US$ 1 billion, with a major surplus on the Russian side. Moscow has been one of the major suppliers of food-stock to Syria, including wheat, flour and sunflower oil, as well as machinery and medicines.17 The purchases of Russia’s wheat is of particular importance for Syria; Moscow provides almost a half of the overall imports. After the fall of the Assad regime, Russian grain shipments to Syria were disrupted.18 Furthermore, all imports from Russia were allegedly banned by the new authorities in January 2025, though this decision has not yet been confirmed. One should also note that many Syrian enterprises run on Russian-built equipment; their maintenance and possible modernization will require continuing reliance on Moscow for at least some time into the future.

Regional Repercussions Begin to Reverberate

Moscow’s officials have expectedly tried hard to downplay the significance of regime change in Syria and its impact on overall Russian positions in the Middle East and the Mediterranean. As Sergey Naryshkin, Head of the External Intelligence Service, stated: “Russia remains a very influential player in the Middle East and both Arab nations and Türkiye understand that. Therefore, there is no threat to Russia’s positions in this region.”19 However, beneath the optimistic rhetoric, there is an intense ongoing search for a recalibrated Russian posture in the region.

Logic and common sense suggest that, after having suffered a major setback in Syria, Moscow should be interested in a continuous balance of external players that would prevent any regional or global actors from acquiring exclusive political influence over Syria’s new authorities. As a minority shareholder in the new Syrian game, the Kremlin could hope to retain a share of its former influence by delicately balancing other active actors in Syria today. Interestingly, when Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke about Syria at the end of December, he referred to Israel rather than Türkiye as “the main beneficiary” of regime change in Damascus,20 predicting that the ongoing massive Israeli air and ground operations would have very serious consequences for future relations between Syria and Israel, and regional stability at large.21 As for Ankara, the official Russian assessment of the Turkish posture in Syria so far has been demonstratively soft and cautious; apparently, in Moscow they still count on Ankara as a responsible player in Syria that is not necessarily interested in reducing Russia’s positions in the country to zero.

However, Russian-Turkish relations might be further complicated by the alleged relocation of Russia’s military hardware and personnel from Syria to the eastern part of Libya.22 This redeployment could be regarded as a part of Moscow’s strategy to put together the so-called “African Corps” as a successor to the Wagner private military company.23 The Khalifa Haftar government in Torbuk may have endorsed this move, but it is explicitly opposed by the Ankara-supported Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh in Tripoli. Other disagreements on Libya might complicate any future Russian-Turkish cooperation in Syria as well.

One can imagine that the best option for the Kremlin would be to see a kind of international consensus around Syria like the one that emerged around Afghanistan after the Taliban returned to power in Kabul in the late summer of 2021. At the end of the day, nobody around Syria should be interested in seeing it split into several failed states controlled by irresponsible and unaccountable non-state state actors — or becoming a hub for international terrorism. Nor would anybody profit from an unstoppable outflow of arms or migrants from the country. Responsible actors around Damascus have stakes in avoiding a humanitarian catastrophe, an inclusive and predictable government, and in Syria rejoining the family of Arab nations. Their common aspirations were reflected in the UN Security Council Statement on Syria, passed in December 2024.24 However, due to geopolitical complications in Ukraine, there have been no notable consultations between the Kremlin, the Biden/Trump Administrations, or major European powers regarding the future of Syria. This inability to communicate with the West is yet another incentive for Moscow to engage closely in dialogue with regional players.

Summing up, the Kremlin is still working on damage-limitation strategies and on defining new approaches to the rapidly changing Mediterranean political and military landscape after the recent regime change in Damascus. At the same time, it is clear that this region, as important as it is, will continue to be upstaged by the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian conflict that supersedes all of Moscow’s other foreign policy challenges and priorities.