“Our Sea”: Europe’s Role in Mediterranean Security

April 2025

Introduction

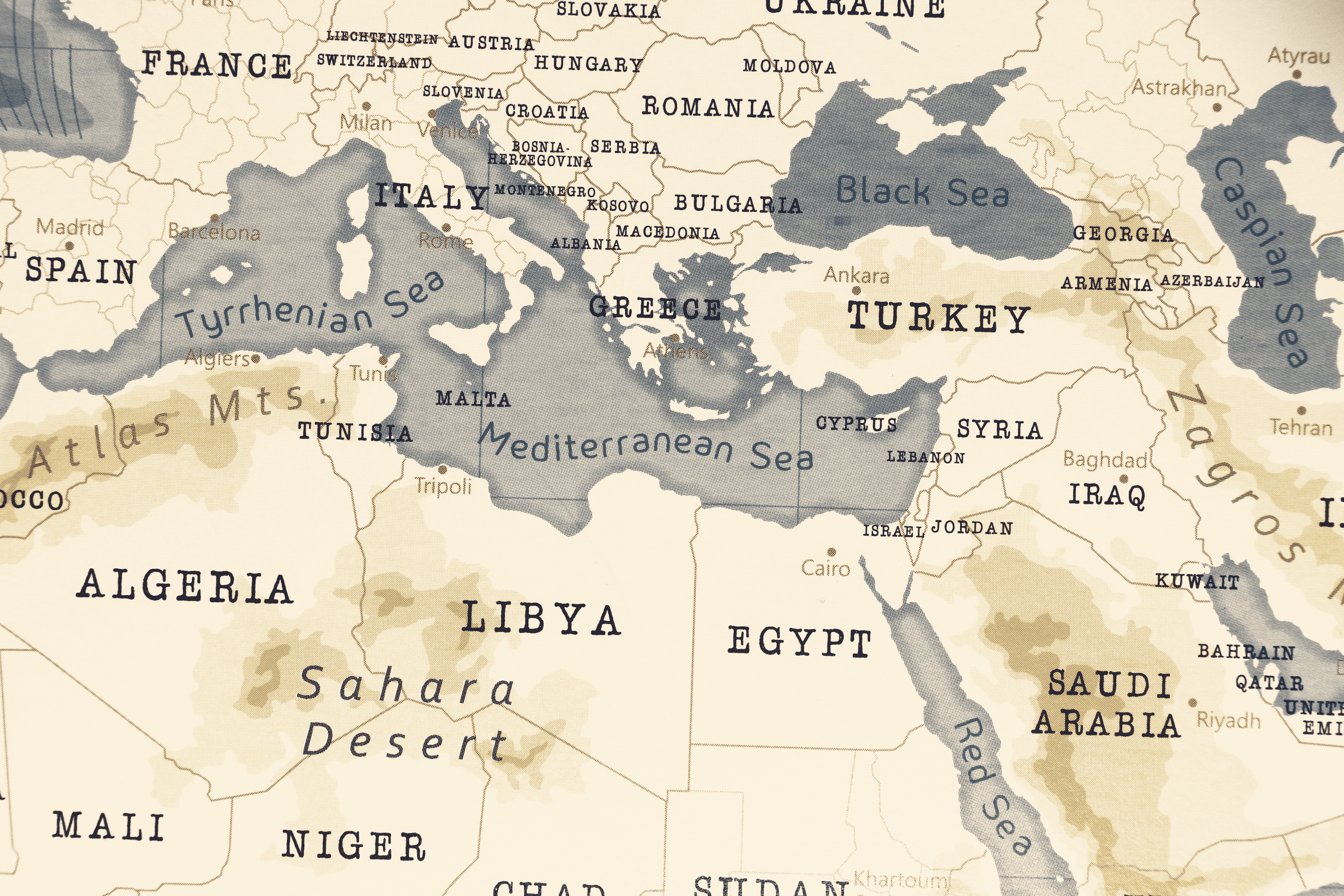

“Mare Nostrum,”1 2013’s Italian operation to rescue migrants, is a fitting analogy for European perspectives on Mediterranean security. Resurrecting the Roman name for the Mediterranean, Our Sea was a unilateral mission to confront illicit migration in-line with European values by focusing on search and rescue (SAR). It came at great cost and with little support from Europe’s administrative heart, the European Commission (EC), receiving just 1.8 million euros.2 Due to political pressure and financial constraints, Mare Nostrum was succeeded just a year later by the European Union’s (EU) Operation Triton, managed by the EU’s border agency Frontex. Operation Triton shifted focus from SAR, following highly political yet thoroughly unevidenced charges that SAR creates a pull factor for further migration.3 Over the years, the mission continued evolving alongside the European threat-perception from their sea. In 2015, Operation Sophia was born, a fully-fledged European Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) targeting people-smugglers. In 2020, as war waged across Europe’s sea in Libya, it evolved once more into Operation Irini with additional responsibilities to enforce a UN arms embargo on Libya while removing any last vestiges of SAR.

The tale of Europe’s evolving Mediterranean missions is instructive regarding European perceptions of Mediterranean security. As a block, the EU represents the Mediterranean’s largest economic and military power. Historically, member states managed their own security, largely limited to targeted threats from transnational organized crime. However, migration represented something new, a perceived collective and existential threat. European political dynamics conjured a perception that demanded securitized solutions over common-sense ones.4

In 2020, Europe’s threat perception evolved again, following heightened tensions with Türkiye over energy rights in the eastern Mediterranean.5 This different kind of threat—towards European dominance over their sea—melded with the ever-growing migration crisis to create Operation Irini. These two cases: Europe’s migration management, and Europe’s attempt to contain Türkiye; demonstrate fundamental European self-perceptions of its security role over their sea, its manifestations, and its implications for the region going forwards.

Mediterranean Migration Management

Compared to neighboring waterways like the Black Sea or Red Sea, the Mediterranean is comparatively bereft of significant security threats. Moreover, defense policy remains the preserve of EU member-states. Until recently, no threat warranted a collective response.

Unsurprisingly, the issue of migration broke the old paradigm. For decades, right-wing political parties were constructing the concept of “fortress Europe,” stirring up cultural and socio-political fears of the other to promote restrictive migration policies without limiting actual socio-economic demands for migrants.6 Illicit migration gradually grew, expedited and exacerbated by the destabilizing counter-revolution to the Arab Spring. In October 2013, this devolving dynamic resulted in over 300 people dying when a rickety migrant vessel sank off the coast of Lampedusa.7 It was a tragedy that shocked Italy, and led to Mare Nostrum, the well-resourced Italian mission that, unlike the EU’s Operation Triton, aimed at protecting migrants’ right-to-life, dignity, and asylum.

Mare Nostrum demonstrated Europe’s dominance of the Mediterranean in terms of setting policy and operational freedom. This was a unilateral mission that, aside from its purportedly good intentions, often sent Italian naval vessels into North African waters to pursue its goals. Italy’s good intentions, however, also triggered a mini political crisis throughout Europe that would lead to collective European security missions into the Mediterranean.

Other major European states wouldn’t fund or support Italy’s mission, leaving Italy feeling abandoned and incapable of preventing thousands of migrants from relocating elsewhere throughout the continent.8 Political pressures and costs led Italy to handover to Operation Triton—removing SAR from the mandate—for a new naval mission that policed European borders rather than the central Mediterranean as a whole.9 It represented a triumph of Europe’s right-wing over migration policy, and by extension a critical part of Mediterranean security, that would only worsen over time.

The 2015 migration crisis further radicalized European securitization of migration and subsequent externalization policies. Operation Triton became Operation Sophia. Again, Europe unilaterally reached across the Mediterranean, pursuing perceived interests aimed at disrupting people-smuggling networks in Libya. Over the subsequent five years, despite being fully aware, the EU was only making migrant crossings more dangerous.10 Operation Sophia continued expanding securitized strategies until the EU mission blended with Italian operations,11 cultivating a coastguard and counter-smuggling force out of Libyan militias. Here, the EU directly intervened to undermine the central government of a fragile transitional state it claimed to support by empowering militias outside governmental control.12

While attempts to combat migration focused on the central Mediterranean, the EU set the tone for eastern and western member states like Greece or Spain whose arrivals surged following every brutal clampdown on the central Mediterranean route. Greece and Bulgaria tried to surreptitiously push back migrants; an innocuous sounding phrase that usually translates to sinking overpopulated boats, or violently driving people back across borders. Spain represented the other side of Europe’s migration policy paradigm, striking externalization deals with Morocco; however, this merely made Spain vulnerable to migration-based blackmail whenever Madrid upset Rabat.

Europe vs Türkiye

Underscoring European migration policies in the Mediterranean is a belief in European supremacy over the region. This enables the EU to project a perception of security priorities and to set a broader policy agenda regardless of efficacy or impact.

European dominance was never meaningfully challenged until Türkiye clashed with Greece and Cyprus over eastern Mediterranean gas fields. It was a long-coming, deeply rooted, dispute catalyzed by the lure of lucrative energy supplies. Ostensibly, this clash was about economic rights in the Mediterranean. Greece follows the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea, which conveniently gives islands the same maritime economic rights as the mainland, effectively making most of the eastern Mediterranean Greece’s exclusive economic zone. Türkiye, along with other Mediterranean nations like Egypt and Libya, or superpowers like the United States don’t follow this convention. Ankara feared losing a potential energy reservoir. Greece attempted to geopolitically subjugate Türkiye through creating the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, which used economics as a gateway for deeper defense partnerships.13 The dispute snowballed as both sides attempted to claim gas fields, and out-maneuver rivals. Greece and Cyprus’ vulnerability before the significantly more powerful Türkiye triggered an avalanche of European support, including sanctions against Türkiye and French military assets deployed to the eastern Mediterranean.14

The East Med became a destabilizing whirlpool, sucking in broader rivalries and other conflicts. Türkiye intervened in Libya’s civil war alongside the internationally recognized government, in exchange for a maritime deal that strengthened their claims. Meanwhile, the UAE, allied with France on the opposing side of Libya’s civil war, joined military exercises in the East Med.

East Mediterranean animosity towards Türkiye blended with ever-rising migration hysteria to further evolve Operation Sophia. Given German attempts to resolve Libya’s worsening war through the Berlin process,15 the EU tried to leverage its CSDP mission to better obstruct the many nations driving Libya’s conflict. However, Greece, Cyprus, and France’s desire to defeat Türkiye’s challenge to European supremacy over the mediterranean—along with Austria, Hungary, and others obsessed with migration—defined the newly created Operation Irini,16 which pushed Europe further away from Mare Nostrum. Its attempts to enforce a UN arms embargo on Libya conspicuously focused on Türkiye’s weapons shipments, conveniently ignoring the thousands of tons of munitions flown to those assaulting Libya’s internationally recognized government.

European attempts to show strength in the eastern Mediterranean neither restored European supremacy, nor prevented its new competitors from making the sea more multipolar. Despite numerous attempts to diplomatically resolve the Turkish-Greek dispute, it eventually drifted into a mutually hurting stalemate where nobody benefitted from the available natural gas reserves. Meanwhile, other competitors like the UAE rode a wave of anti-Turkish sentiment, entrenching it regionally. Other antagonistic EU rivals, like Russia, benefitted from the chaos in Libya.

Looking Ahead

Given that Europe will continue to collectively be the region’s strongest economic, military, and diplomatic actor, its hegemonic status over the Mediterranean and its sense of supremacy are unlikely to change anytime soon. However, recent experiences with the sea’s two major security issues—the ‘cold war’ in the eastern Mediterranean and Europe’s securitization of migration—have established trends that will continue to destabilize the Mediterranean and Europe’s role as a security provider.

A primordial issue driving insecurity in the Mediterranean and European fragmentation has been the rise of Europe’s right-wing and their associated politics of fear. This dynamic is best captured by migration policy’s continuing growth to define Mediterranean security, while destabilizing the region and enabling competitors to better challenge Europe. European externalization policies are predicated on closing Europe’s borders, without removing the driving forces for migration, which means illicit migration will continue growing. So, Europe is effectively driving the growth of the people-smuggling industry, putting more money into the hands of transnational criminal gangs and other destabilizing actors. This will solicit ever bigger, and more expensive European responses, whilst southern Mediterranean countries and non-state actors will adopt counter-migration language to receive EU financing and support. Moreover, as the problem inevitably continues to worsen, fractures between European states widen, hurting the EU’s capacity to mount cohesive policy responses to other security issues, as seen with Libya.

European supremacism also carries a strong strain of European exceptionalism that sets destabilizing precedents and weakens Europe’s value-proposition to other southern neighborhood states at a time of intensifying competition. Although some European actors tried to mediate, collective EU support for Greek attempts to strong-arm Türkiye catalyzed the antagonistic politics of domination over diplomacy in the region. Europe’s myopic focus also blinded them to the damage caused to other interests, such as in Libya. This supremacism coupled with the politics of fear fosters a new unwritten doctrine of strongman politics for Europe in the Mediterranean. Europe is supporting authoritarians like Libya’s Haftar,17 contrary to values at the heart of the EU’s foundational treaties. This helps denigrate the global rules-based order and Europe’s reputation while weakening its proposition as an ally in the face of rivals like Russia, Türkiye, or the UAE who are much more effective at being transactional. This dynamic culminated with Europe’s blind support to Israel’s genocide in Gaza, and egregious destruction of Lebanon, whilst using the “global rules-based order” to solicit global support against Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine.

Given dynamics instituted by Europe this past decade, Mediterranean security is headed towards destructive contestation. The next ten years will be defined by the ripples from the annihilation of Gaza, the worsening migration crisis, and the aggressive growth of a new Emirati-Russian coalition across Africa. Unless Europe adopts a more cohesive, forward-looking, pragmatic, and inclusive approach to Mediterranean security, it will not only lose its dominance, but the Mediterranean will lose its position of relative stability too.

Endnote

1 This Latin term translates to “Our Sea.”

2 “Frontex Joint Operation ‘Triton’ – Concerted Efforts to Manage Migration in the Central Mediterranean,” European Commission, October 7, 2014, ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/memo_14_566.

3 Alejandra Rodríguez Sánchez et al., “Search-and-Rescue in the Central Mediterranean Route Does Not Induce Migration: Predictive Modeling to Answer Causal Queries in Migration Research,” Scientific Reports 13 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38119-4.

4 Mattia Toaldo, Don’t Close Borders, Manage Them: How to Improve EU Policy on Migration through Libya, Policy Analysis, (Berlin: European Council on Foreign Relations, June 15, 2017), https://ecfr.eu/publication/dont_close_borders_manage_them_7297/.

5 Asli Aydintasbas et al., “Overview: Fear and Loathing in the Eastern Mediterranean,” European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) MENA Team, May 2020, https://ecfr.eu/special/eastern_med/.

6 Lorena Martini and Tarek Megerisi, Road to Nowhere: Why Europe’s Border Externalisation is a Dead End, Policy Brief, (Berlin: European Council on Foreign Relations, December 14, 2023), https://ecfr.eu/publication/road-to-nowhere-why-europes-border-externalisation-is-a-dead-end/#building-fortress-europe.

7 “Italy Boat Sinking: Hundreds Feared Dead Off Lampedusa,” BBC, October 3, 2013, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-24380247.

8 Adam Taylor, “Italy Ran an Operation that Saved Thousands of Migrants from Drowning in the Mediterranean. Why Did It Stop?,” Washington Post, April 20, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/04/20/italy-ran-an-operation-that-save-thousands-of-migrants-from-drowning-in-the-mediterranean-why-did-it-stop/.

9 Duncan Robinson, “Alarm at Plan to End Italy’s Mare Nostrum Rescue Operation,” Financial Times, October 12, 2014, https://www.ft.com/content/ec9edf84-508e-11e4-8645-00144feab7de.

10 Zach Campbell, “Europe’s Deadly Migration Strategy,” Politico, February 28, 2019, https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-deadly-migration-strategy-leaked-documents/.

11 James Reynolds, “Marco Minniti: The Man who Cut the Migrant Flow to Italy,” BBC, September 20, 2018, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-45575763.

12 Lorena Martini and Tarek Megerisi, Road to Nowhere.

13 Asli Aydintasbas, “Turkey: A Deal Is Possible,” European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) MENA Programme, May 2020, https://ecfr.eu/special/eastern_med/turkey.

14 “France Stokes Turkey Tensions by Sending Naval Vessels to Waters Off Cyprus,” Financial Times, August 13, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/465ba697-451f-4601-b1a7-02eca6680edc.

15 “Berlin International Conference on Libya – 19 January 2020: Conference Outcomes,”, United Nations Support Mission in Libya, January 19, 2020, https://unsmil.unmissions.org/berlin-international-conference-libya-19-january-2020

16 Tarek Megerisi, “The EU’s ‘Irini’ Libya Mission: Europe’s Operation Cassandra,” European Council on Foreign Relations, April 3, 2020, https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_the_eus_irini_libya_mission_europes_operation_cassandra/.

17 Karim Mezran and Aldo Liga, “After anti-migration efforts shrank its influence, Rome needs a new Libya policy,” Atlantic Council, 30 July 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/after-anti-migration-efforts-shrank-its-influence-rome-needs-a-new-libya-policy/