Iran’s Neighborhood Policy: An Assessment

April 2024

Introduction

Soon after his election to the Iranian presidency in 2021, Ebrahim Raisi declared that one of his key foreign policy objectives would be to improve Iran’s relations with neighboring countries. Within months, the new administration in Tehran articulated a “neighborly policy” (siyasat-e hamsayegi) that has at its core improved relations with Iran’s Arab neighbors and especially with Saudi Arabia.1 Efforts at improving post-revolutionary Iran’s relations with its neighbors are not new, having featured prominently in the administrations of former presidents Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Mohammad Khatami, and Hassan Rouhani. However, this is the first time that the Iranian government has formally adopted the good neighbor policy as a formal doctrine.

This chapter examines the hitherto unexplored parameters and objectives of Raisi’s new foreign policy doctrine. It argues that Tehran’s deliberate pursuit of good relations with neighboring states has combined with a number of factors outside of Iran’s control—not least of which is Saudi Arabia’s recent receptivity to Iranian overtures—to bear significant results. Raisi, with an earned reputation as a conservative, has largely succeeded in an area where Iranian reformists and moderates have tried but failed. This partial but important success is not all Raisi’s doing, having been greatly aided by a number of larger structural factors unfolding in the Gulf region, in the broader Middle East, and beyond. Nevertheless, the Iranian president deserves credit for having greatly reduced tensions between Iran and most of its neighbors.

Despite occasional efforts by the Islamic Republic’s leaders to improve Iran’s relations with its Arab neighbors—notably by presidents Rafsanjani, Khatami, and Rouhani—Iran-Arab relations have remained consistently tense since the 1979 Iranian revolution.2 An Iran-Arab cold war of sorts was set off, in fact, when in January 2016 mobs in Tehran and Mashhad attacked the Saudi embassy and consulate, respectively, and set the buildings on fire.3 These attacks occurred against a backdrop of civil wars in Syria and Yemen, where Iran and many of its Arab neighbors found themselves supporting opposing sides. In fact, Syria and Yemen became primary battlegrounds where proxy groups supported by Iran fought with those financed by Saudi Arabia and its Arab allies. Tehran, meanwhile, frequently accused Riyadh and Manama of interfering in its internal affairs and fomenting unrest in the country.4 Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, for their part, maintained that Iran continued to harbor ambitions of exporting its revolution, destabilizing the region, and disrupting the free flow of energy out of the Gulf.5 Not known for holding back his opinion, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman at one point even likened Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei to Hitler.6

In pursuing its good neighborly relations, Tehran has decided that Saudi Arabia is key to improving its relations with the rest of the Arab world. As far as Tehran is concerned, Saudi Arabia engages in “dollar diplomacy,” using its financial prowess to ensure that less-wealthy Muslim-majority countries keep Iran at arm’s length.7 The Iranian government has decided that as long as the Saudis entice or threaten other Arab capitals to remain cold toward Tehran, broader Arab-Iranian relations will not improve.8 Significantly, therefore, when it comes to Saudi Arabia, Iran’s notoriously fractious state has, since 2021, been remarkably unified in its consistent advocacy of improved relations with the kingdom. Despite Iranian persistence, however, until the March 2023 deal, Riyadh saw little to no strategic gains in engaging in substantive dialogue and tension-reduction measures with Iran. Instead, relations between the two sides were characterized by mutual mistrust.9

While Iran’s stated adoption of good neighborly policy may be recent, neither the overall approach nor its manifold benefits are new. The chapter therefore starts with a brief examination of the concept of neighborhood, the necessary preconditions making it possible, and the likely motivation for adopting it. It then examines attempts by Iran to pursue good neighborly relations, albeit often half-heartedly. Apart from specific political and strategic considerations that may surface from time to time, three sets of structural factors—at the domestic, regional, and international levels—undermine Tehran’s effective implementation of good neighborly policy with most of the regional Arab states. Until and unless these domestic, regional, and international obstacles are resolved, Iranian efforts at improving relations with neighbors, especially its Arab neighbors, will remain at best only partially effective.

The Good Neighborly Policy

Iran’s first serious attempt in a decade at deepening relations with its neighbors started in 2017 in relation to Qatar in the aftermath of what came to be known as “the Gulf crisis.”10 The two states, which found themselves on opposite sides in 2011 after the beginning of the Arab uprisings, took steps to improve relations after the imposition of sanctions against Doha by Saudi Arabia and its allies.11 The development of these relations gradually led Iran to hope for an improvement in its relations with other Arab states. In this regard, Iran’s most significant good neighborhood policy measure was taken in 2019 under the auspices of the Hormuz Peace Initiative (HOPE), introduced by President Hassan Rouhani’s administration.12 The proposal, first presented at the 74th United Nations (UN) General Assembly, was designed to find solutions to secure the Gulf and to ensure “energy security, freedom of navigation, information exchange, arms control, conflict prevention, and non-aggression.”13 Despite containing a series of measures aimed at building trust and fostering multilateral cooperation, the proposal failed to elicit positive responses from Iran’s Arab neighbors.14 At the time, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) were especially hopeful that the United States’ (U.S.) policy of “maximum pressure” on Iran would bear fruit and lead to regime change, or at least a change in the behavior of Iranian leaders. But President Donald Trump’s “maximum pressure” policy proved less than effective. A new U.S. presidential administration took office in 2021, and the Saudis and Emiratis began to feel the heat of their missteps in the war they had launched against Yemen in 2015. Slowly, the kingdom began to realize that détente with Iran might be to its advantage.15

For Saudi Arabia, several factors appear to have been at work. These considerations included an unpopular and unwinnable war in Yemen; the apparent failures of highly confrontational policies toward both Iran and Qatar; the compound effects of the COVID-19 pandemic; and the need to rehabilitate its global image in the aftermath of murdered Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. Focusing on internal economic development—especially on the ambitions of Vision 2030 and on massive infrastructural projects—also appears to have influenced Saudi receptivity to tension-reduction measures with Iran.

All of this has been happening within the context of an apparent reduction in U.S. diplomatic engagement in the Middle East, at least as perceived through regional capitals.16 For the Saudis, the seeming U.S. withdrawal from the region has made rapprochement with Iran not just desirable, but in many ways a necessity. The simmering down of the Syrian civil war and the country’s steady reintegration back into the Arab fold, especially the thaw in its relations with Riyadh, also appear to be crucial to Saudi’s receptivity to improved relations with Iran.17 In his 2021 speech to the UN General Assembly, Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud softened his previously harsh tone toward Iran: “Iran is a neighboring state,” he said. “We hope that initial talks with Iran will lead to concrete confidence-building measures, measures that will achieve the aspiration of two peoples for collaborative relations based on the commitment to the principles and resolutions of international legitimacy, respect for sovereignty, and non-interference in internal affairs.”18

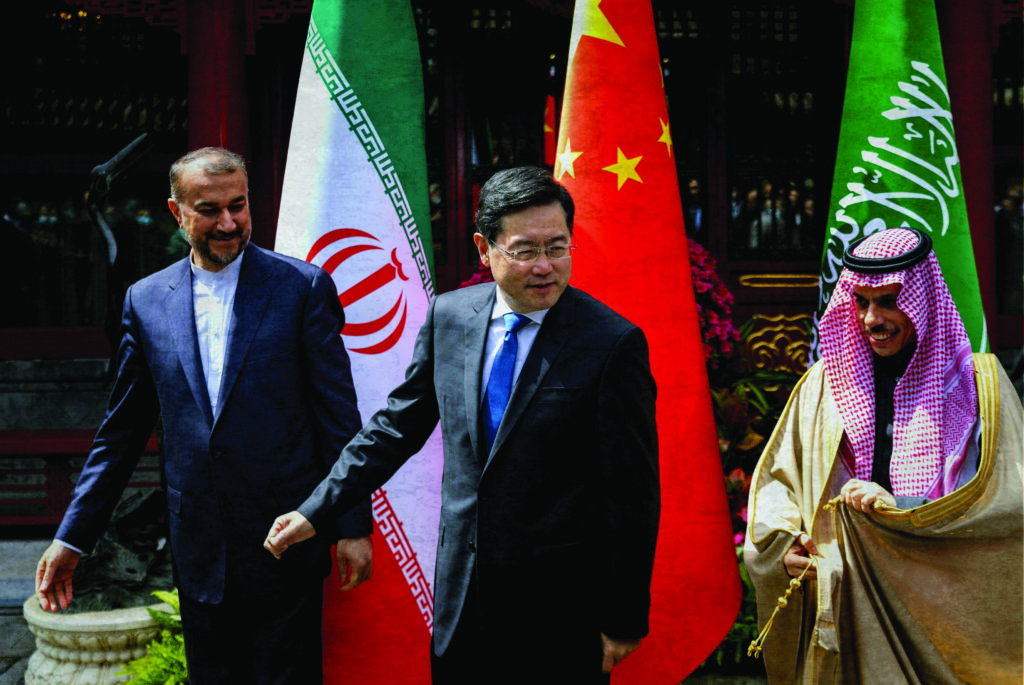

For its part, Iran sees reducing tensions with Saudi Arabia as the most important hallmark of its neighborhood policy. From Iran’s perspective, détente with Saudi Arabia can be a starting point for improving relations with other Arab states and establishing peace and stability in the region. For this reason, the Raisi administration has considered the neighborhood policy as a main priority of Iran’s international relations. Finally, in March 2023, as a result of secret negotiations conducted in Beijing, which had been going on for some time through mediation efforts by Iraq and Oman, Iran and Saudi Arabia announced a resumption of diplomatic relations and the start of a new era in their policies toward each other.19

Significantly, shortly after the start of Iran-Saudi rapprochement, Iran and Bahrain announced the start of a series of confidence-building and tension-reduction measures as well, among them a resumption of passenger flights, visits by parliamentary delegations, and, eventually, restoration of diplomatic ties that were severed in 2016.20 Meanwhile, Iran and the UAE had started a number of high-level security engagements that dated back to the Rouhani administration. Such exchanges became more frequent and more substantive once Raisi took office, culminating in the formal establishment of full diplomatic relations between the two sides in April 2023.21

A potential flashpoint for Iran has been its porous eastern borders with Afghanistan and Pakistan. In recent years, in fact, a number of Iranian border guards and soldiers have been killed in attacks the Iranian government had attributed to smugglers and “terrorists.”22 Nevertheless, Iranian authorities have consistently taken great care to downplay the gravity of the situation and instead emphasize the degree to which Iran’s relations with both Islamabad and Kabul remain cordial. When, in May 2023, as many as six Iranian soldiers were shot and killed from inside Afghanistan by Taliban forces, Iranian officials were quick to dismiss the event as nothing more than a “minor incident,” akin to a “family dispute.”23 Dialogue, Iran’s interior minister insisted, is the only way for the two sides to resolve their differences.24

Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian has indicated that de-escalation with Saudi Arabia is key to reconciliation with other Arab states: “We need more dialogue. We and Saudi Arabia [have] reached agreements on certain issues, and we welcome this dialogue. Our dialogue with Saudi Arabia is useful and constructive to the region. Iran and Saudi Arabia are two important countries and play very important roles in stabilizing regional security.”25 Another ranking administration official, Mohammad Jamshidi,26 echoed the foreign minister’s statement: “One of the main foundations of the government’s foreign policy is the neighborhood policy, maximal interaction, and economic multilateralism.”27 In January 2022, Iran’s Foreign Ministry held a high profile conference titled “Neighborhood,” during which the interior minister, Ahmad Vahidi, went so far as to propose the establishment of a “Ministry of Neighboring Affairs” tasked with advancing the government’s neighborhood policy.28 “The problem with the neighbors is not caused by the lack of an organization or the lack of the Ministry of Neighboring Affairs,” another speaker responded. “Rather, the problem is related to perceptions, policies, historical and political events, and actions and reactions that change the direction of events in the region.”29

Conclusion

At the broadest level, Iran’s neighborhood policy is motivated by the overarching objective of creating a new regional order. In accomplishing this aim, the Islamic Republic is pursuing a number of goals that may be broadly categorized as political, security, cultural, and economic. The policy represents the first time since the revolution that the Iranian government has actually articulated and labeled a proactive foreign policy approach. In the past, factional infighting often made Iranian foreign policy at best reactive.30 Under Raisi, good neighborly relations, and its complementary “Look East” policy, so far appear to have achieved a number of their stated objectives. All Iranian presidents since 1981 have had a track record of serving a second term. Barring unforeseen developments, Raisi’s foreign policy approaches are likely to continue at least until 2029. If this indeed does happen, Iran is likely to see a continued deepening of political and economic relations, and perhaps even security cooperation, with its neighbors.