IMEC’s Ambitious Gamble: Overcoming Geopolitical Obstacles in a Fractured Mediterranean

March 2025

Introduction

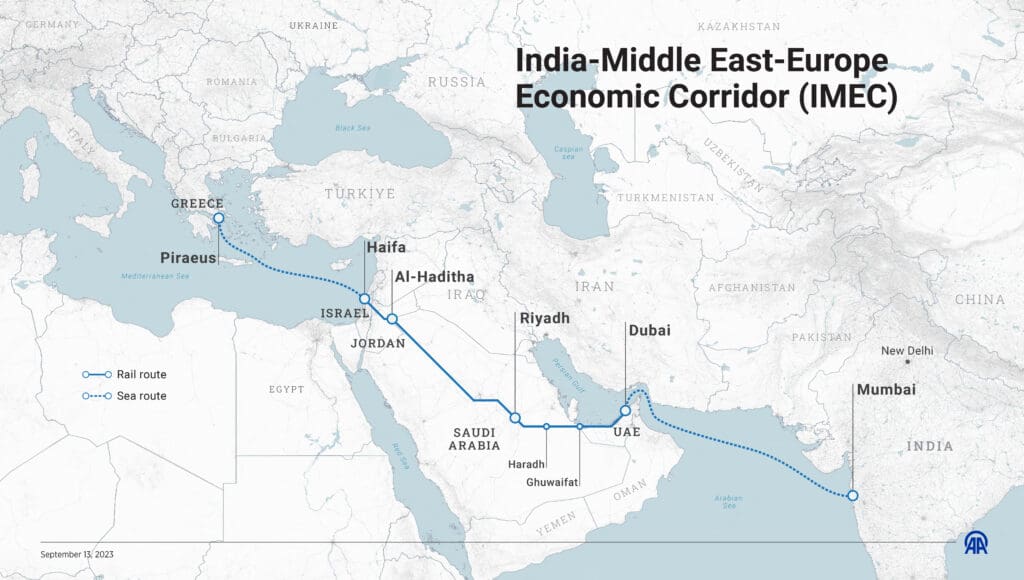

The September 2024 India-UAE Virtual Trade Corridor agreement1—designed to streamline trade and reduce logistics costs—was met with celebration in Indian media, highlighting India’s proactive role in advancing the ambitious India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC).2 This enthusiasm, however, may be premature. While the Corridor was formally introduced during the 2023 G20 summit in New Delhi—with the EU, the United States, and other countries signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU)—translating this vision into reality faces formidable challenges.

Envisioned as a multimodal trade route connecting India to Europe via the Middle East, IMEC proposes a ship-to-rail system bypassing the Suez Canal, potentially reducing shipping times by 40%.3 Beyond transport, IMEC aims to foster digital connectivity, establish a renewable energy grid, and facilitate a green hydrogen pipeline, offering Europe an alternative energy source to natural gas and other hydrocarbons from Russia.4 However, this necessitates overcoming significant technical and financial obstacles. Constructing the required infrastructure across diverse terrains and jurisdictions demands immense investment and coordination. Securing long-term commitment from stakeholders, particularly in the face of competing priorities and the established presence of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), poses a further challenge.

Yet, the most formidable hurdle remains the complex geopolitical landscape. Regional tensions create a volatile environment: the Saudi-Iranian rivalry, Israel’s tense relations with Iran, the ongoing genocide in Gaza, the war on Lebanon, and conflict in Syria and Yemen. For instance, Yemen presents a significant challenge to Saudi Arabia’s security and IMEC, creating volatility along the border—with cross-border attacks and the spread of extremism—diverting resources away from economic development. Furthermore, it could disrupt the Corridor’s physical infrastructure, particularly the planned railway line through Saudi Arabia and Jordan. Security concerns, political disputes, or even sabotage could hinder the railway, potentially jeopardizing IMEC’s long-term success.

Also, Türkiye, a pivotal player in the Mediterranean, has voiced its strong opposition to IMEC, asserting its strategic importance in the region. Erdogan has explicitly stated, “We say that there is no corridor without Türkiye,”5 underscoring any viable economic corridor in the region must include Türkiye’s participation. This further complicates the project’s prospects for success.

To better understand these challenges, it’s important to consider IMEC’s geographic scope. IMEC envisions a multimodal network originating in India, traversing the UAE, and utilizing a rail system across Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel (Haifa Port) before reaching European ports — Piraeus in Greece, largely operated by Chinese Cosco—via the Mediterranean Sea. This raises concerns about the feasibility of constructing infrastructure and securing long-term commitments. Besides, bypassing the Suez Canal raises questions about the implications for Egypt’s economy and national security. The Suez Canal is a major global trade artery, generating substantial revenues for Egypt. In 2023, the Canal’s annual revenues reached a record of $9.4 billion.6

The ongoing conflicts in Gaza, Lebanon, Yemen, and Syria could make investors and stakeholders hesitant to commit to IMEC, given the risks associated with operating in such volatile environments. Ultimately, the lack of sustainable peace and de-escalation between Israel and Hamas threatens the very existence of IMEC, potentially derailing the entire project before it truly takes shape.7

The Saudi-Iranian Fault Line: Implications for IMEC

The success of IMEC hinges on regional stability and cooperation, yet the reality on the ground presents significant challenges. Despite some progress in relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia, lasting trust remains elusive. This is partly due to their opposing views on Iran’s continued support for the Houthis in Yemen, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and various Shia militias in Iraq and Syria. Without a more stable foundation in this crucial relationship, long-term planning and investment in IMEC may prove challenging.

Ongoing proxy conflicts between the two regional powers, fueled by years of mistrust, cast a shadow over the IMEC project. While the 2023 China-brokered rapprochement between Riyadh and Tehran offered a glimmer of hope, this reconciliation remains fragile, particularly considering recent events.8

In Yemen, the agreement initially curbed Houthi aggression towards Saudi Arabia, prompting Riyadh to engage in direct negotiations with the Houthis. However, the recent Gaza war has disrupted these efforts. The Houthis, in solidarity with Palestine, engaged in attacks on international commercial vessels in the Red Sea, disrupting vital trade routes and escalating regional tensions. This renewed instability jeopardizes and undermines prospects for Saudi-Houthi talks towards a final roadmap.

Meanwhile, Yemen remains a devastated battleground in the broader Saudi-Iranian rivalry. With 4.5 million people displaced, 17.6 million facing hunger, and 80% living in poverty, the country is witnessing “one of the worst ongoing humanitarian crises in the world.”9

IMEC: Navigating the Israeli Factor

The ongoing genocidal campaign in Gaza10 and the fragile ceasefire with Lebanon, coupled with the potential for escalating tensions with Iran, cast a shadow of instability over the entire region and significantly diminish its attractiveness for trade — businesses and investors naturally seek stability and predictability.

Israel and its allies partly drive the IMEC project, aimed at fostering normalized relations with Arab states. This goal faces significant challenges. IMEC’s collaboration with Israel could negatively impact the image of participating governments and potentially lead to internal instability.11 Even before October 7, 2023, public support for normalization with Israel was already very low in the region, as evidenced by Arab Barometer.12 The events of October 7 further shifted the landscape, resulting in substantial reputational damage and a loss of global credibility for Israel and its allies,13 further complicating normalization efforts.

Israel’s genocidal campaign in Gaza after Hamas’s Al Aqsa Flood reverberated throughout the region, triggering a cascade of responses and a worsening security environment. First, in Lebanon, in response to Hezbollah’s attacks on northern Israel, Israel launched a brutal campaign that devastated southern Lebanon, including the assassination of Hezbollah’s leader.14 Israeli attacks have inflicted a heavy toll on Lebanese civilians, with the Health Minister reporting 1,640 fatalities and 8,408 injuries.15 Israel’s relentless bombing has triggered a mass exodus of civilians, forcing an estimated 1 million people — a staggering 20% of the population — to flee their homes.16

Second, already weakened by protracted civil war, Syria faces further destabilization from frequent Israeli airstrikes targeting Iranian and Hezbollah positions within its borders. As Syria embarks on its post-Assad chapter, Israel is planning further settlement of the occupied Golan Heights, aggravating regional tensions.

Third, following the Israeli bombing of its embassy in Damascus in April, Iran retaliated with missile strikes, resulting in a relentless tit-for-tat cycle, with each side responding in kind, further escalating hostilities.

Israel’s internal political instability, exacerbated by the ongoing wars in Gaza and Lebanon, has placed a significant, considerable strain on the country’s finances. This raises serious questions about its capacity to commit to an ambitious project like IMEC.

The conflict has forced a shift in priorities, diverting substantial resources towards military spending and incurring the costs of sustained displacement for border-area residents. As Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich acknowledged, “Israel’s economy bears the burden of the longest and most expensive war in the country’s history.”17 The economic repercussions are already being felt, with Israel’s credit rating downgraded twice, and further downgrades anticipated.18

Additionally, the logistical viability of IMEC is in question, particularly given the challenges facing key infrastructure like Haifa port. The port, once envisioned as a critical hub for the Corridor, is now grappling with security issues that threaten to disrupt operations, increase costs, and undermine investor confidence. The recent Hezbollah attacks shattered its image as a safe and reliable hub and cast a shadow over its intended role in IMEC. Specifically, maritime security and industry groups have elevated their risk assessments for the port, acknowledging the potential for disruption, delays, and increased costs.19 Despite assurances from the Israeli government, security measures have been heightened at the port and along the entire IMEC route — potentially derailing the project compared to established alternative trade routes.

The Appeal of Alternatives

While India has shown enthusiasm for IMEC and France has demonstrated commitment by appointing a special envoy, IMEC still faces significant headwinds, including logistical and financial hurdles, and the challenge of garnering widespread regional support.20 Several factors contribute to this lukewarm reception, raising questions about the Corridor’s long-term viability.

First, the exclusion of key regional players such as Qatar, Egypt, Türkiye, and Iran, raises questions about the Corridor’s inclusivity and long-term viability. Second, the non-binding nature of the current MoU, coupled with the absence of signatures from key players like Israel and Jordan — noted as transit points for IMEC — casts a shadow on IMEC’s future.

Third, aligning with IMEC, a project closely associated with the United States, Israel, and its European allies, carries potential risks for regional states. Regional public opinion is increasingly critical of Western complicity in Israel’s actions in Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon, and Syria, and any perceived association with those policies could generate domestic backlash. This sentiment is reflected in recent surveys, such as the Arab Index, which found overwhelmingly negative views of the U.S. role in the Gaza war. A staggering 94% of respondents held a negative view, with 82% rating it as “very bad.” This disapproval extends to key European allies as well, with France, the UK, and Germany viewed negatively by 79%, 78%, and 75%, respectively. These findings underscore the potential political costs associated with any perceived alignment with Western powers, even on economic initiatives like IMEC.21

Fourth, the project is perceived as undeveloped and potentially unfeasible, particularly given the lack of a clear alternative to China’s BRI. The absence of a viable alternative to BRI stems from several factors. BRI is deeply entrenched in the region, with many countries having existing investments and projects linked to it. Besides, BRI offers a comprehensive package of infrastructure development, financing, and trade opportunities that are attractive to many countries in the region. Also, China’s continued dominance as the largest consumer of Gulf hydrocarbon exports further complicates matters. While the UAE’s emergence as a major investor in connectivity infrastructure — especially in Africa — offers a potential alternative to China’s BRI, it is not yet on the same scale. Therefore, the potential costs of jeopardizing these relationships with China, without a guaranteed and immediate alternative, outweigh the uncertain benefits of aligning with IMEC.

Finally, the rise of multipolarity in the international system has empowered regional states to assert their strategic autonomy. Perceptions of a U.S. pivot towards Asia fueled anxieties among Gulf countries, prompting them to diversify their partnerships and pursue a more independent foreign policy. Saudi Arabia exemplifies this by exploring Chinese support for its civilian nuclear program to develop uranium mining, milling, and enrichment capabilities. This is a strategic move aimed at enhancing its negotiating leverage with the United States. This evolving geopolitical landscape underscores the growing assertiveness of regional powers. The announcement of the Development Road project — a homegrown corridor initiative involving Türkiye, Iraq, Qatar, and the UAE — exemplifies this trend. The participation of Qatar and the UAE in this project signals their commitment to regional cooperation and their ambition to exercise growing influence as middle powers.

The Development Road presents a compelling alternative to the troubled IMEC. Unburdened by the political baggage that plagues IMEC, the Development Road’s prospects for success appear brighter, especially that it is believed to be more cost-effective than IMEC.22 Its alignment with Türkiye’s Middle Corridor within BRI offers access to a wider market, potentially eclipsing IMEC’s reach. For now, the Turkish route seems poised to dominate the race to establish a viable trade corridor.

In conclusion, IMEC faces a complex web of challenges, from logistical hurdles and financial constraints to geopolitical risks and regional uncertainties. However, amidst these challenges lies opportunity. Rather than rely on external powers to dictate terms, it is time for countries to forge their own paths, leverage their strategic location, economic resources, and diplomatic influence to create a more interconnected and prosperous region, to take the lead in shaping their future.

Endnote

1 “India, UAE Launches Virtual Trade Corridor to Enhance Ease of Doing Business,” Times of India, September 11, 2024, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/india-uae-launches-virtual-trade-corridor-to-enhance-ease-of-doing-business/articleshow/113256441.cms.

2 “India Readies Its Ports to Power the Ambitious IMEC Corridor,” Business Today, September 11, 2024, https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/economy/story/india-readies-its-ports-to-power-the-ambitious-imec-corridor-445481-2024-09-11.

3 “The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC),” HSBC Business Go, accessed October 31, 2024, https://www.businessgo.hsbc.com/en/article/imec-economic-corridor.

4 The immense cost and logistical complexities of developing a hydrogen economy raise concerns about its feasibility. Furthermore, the efficiency and viability of hydrogen for widespread commercial use, especially in transportation and heating, remain unproven. Adam Tooze, “Hydrogen Is the Future—or a Complete Mirage,” Foreign Policy, July 14, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/07/14/hydrogen-is-the-future-or-a-complete-mirage/.

5 Ragip Soylu, “Turkey’s Erdogan Opposes India-Middle East Transport Project,” Middle East Eye, September 11, 2023, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkey-erdogan-opposes-india-middle-east-corridor.

6 “Suez Canal Annual Revenue Hits Record $9.4 Billion, Chairman Says,” Reuters, June 21, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/suez-canal-annual-revenue-hits-record-94-bln-chairman-2023-06-21/.

7 EU Diplomate, interview by author, Doha, October 2024.

8 International Crisis Group, Great Expectations: The Future of Iranian-Saudi Détente, Middle East Briefing no. 92, (Tehran/Riyadh/Washington/Brussels: International Crisis Group, June 13, 2024), https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iran-saudi-arabia/b92-great-expectations-future.

9 “Yemen: Justice Remains Elusive and Millions Still Suffering Nine Years since Armed Conflict Began,” Amnesty International, March 25, 2024, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/03/yemen-justice-remains-elusive-and-millions-still-suffering-nine-years-since-armed-conflict-began/.

10 The Israeli genocidal campaign in Gaza has resulted in a staggering loss of life, with at least 42,924 people killed, including nearly 16,765 children, over 100,833 injured, and more than 10,000 remain missing.

11 Anna Gordon, “New Poll Shows How Much Global Support Israel Has Lost,” Time, January 17, 2024, https://time.com/6559293/morning-consult-israel-global-opinion/.

12 Michael Robbins, “How Do MENA Citizens View Normalization with Israel?,” Arab Barometer (blog), September 21, 2022, https://www.arabbarometer.org/2022/09/how-do-mena-citizens-view-normalization-with-israel/.

13 Yasmeen Serhan, “How Israel and Its Allies Lost Global Credibility,” Time, April 4, 2024, https://time.com/6963032/israel-netanyahu-allies-global-standing/.

14 Maya Gebeily and Milan Pavicic, “Israeli Campaign Leaves Lebanese Border Towns in Ruins, Satellite Images Show,” Reuters, October 29, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/israeli-campaign-leaves-lebanese-border-towns-ruins-satellite-images-show-2024-10-28/.

15 “Lebanese Health Minister Reports 1,640 Dead, 8,408 Injured from Israeli Attacks since October 8,” Qatar News Agency, September 28, 2024, https://www.qna.org.qa/en/News-Area/News/2024-09/28/0024-lebanese-health-minister-reports-1,640-dead,-8,408-injured-from-israeli-attacks-since-october-8.

16 Olivia Giovetti, “The Crisis in Lebanon, Explained,” Concern Worldwide US, October 2, 2024, https://concernusa.org/news/lebanon-crisis-explained/.

17 Hanna Ziady, “Israel’s Economy Could Be the Next Casualty of War with Hamas,” CNN, October 4, 2024, https://edition.cnn.com/2024/10/04/economy/israel-economy-war-impact/index.html.

18 Steven Scheer, “More Ratings Cuts Feared After Moody’s Downgrades Israel Two Notches,” Reuters, October 1, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/more-ratings-cuts-feared-after-moodys-downgrades-israel-two-notches-2024-10-01/.

19 Jonathan Saul, “Maritime Industry Raises Threat Level for Israeli Ports,” Reuters, September 28, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/maritime-industry-raises-threat-level-israeli-ports-2024-09-27/.

20 Retired Indian diplomate, interview by author, Doha, October 2024.

21 Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, “Arab Public Opinion about the Israeli War on Gaza,” Doha Institute, January 10, 2024, https://arabindex.dohainstitute.org/EN/Pages/APOIsWarOnGaza.aspx#.

22 “Choosing Paths: Development Road or IMEC, which Benefits Trade more?,” Fibre 2 Fashion, April 30, 2024, https://www.fibre2fashion.com/news/textiles-logistics-news/choosing-paths-development-road-or-imec-which-benefits-trade-more–294895-newsdetails.htm.