Iran's Policy,

and Its Relations with China and Russia

Issue Brief, September 2023

Key Takeaways

Abandoning Non-Alignment: The principle of “neither East nor West” as the main foreign policy pillar of post-revolutionary Iran is no longer relevant. In other words, non-alignment as the basis of the Islamic Republic’s foreign policy has given way to efforts to form a bloc in partnership with Eastern powers.

Limited Foreign Policy Options: Although looking East has come with some important benefits for Iran, it has severely limited the country’s foreign policy options. Moreover, this limiting comes at a time when Iran’s neighbors have succeeded in gaining more maneuvering space by successfully balancing between the East and the West.

Reinforced Authoritarianism: At the domestic level, the “Look East” policy reinforces authoritarianism and promotes a security-oriented mindset in foreign relations, driven by the growing influence of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and its desire to establish a solid partnership with Russia.

Sanctions as a Main Challenge: Iran’s Eastern partners are still sensitive to their relations with the West, especially with the United States. Therefore, Iran’s economic interests cannot be achieved by only looking to the East without resolving issues with the West and securing the lifting of sanctions.

Introduction

Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iran aimed to establish an independent foreign policy, free from the influence of Western and Eastern powers. However, as time passed, escalating conflicts with the West amplified the prominence of the anti-Western pillar in Iran’s foreign policy. A significant manifestation of this stance has been a strategic pivot to the East, where nations such as China and Russia have been considered as key partners and alternatives to the West.

Iran’s “Look East” policy is generally understood as a strategy aimed at fostering stronger political, economic, and strategic connections with countries in the Eastern hemisphere, particularly in Asia, with the goal of broadening alliance networks and diminishing Iran’s susceptibility to Western powers’ influence. This issue brief offers a detailed analysis of Iran’s “Look East” policy––a strategy that has been pursued and evolved under three consecutive presidents: Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013), Hassan Rouhani (2013-2021), and Ebrahim Raisi (2021-present). Despite divergences in their respective approaches, this paper argues that two fundamental similarities exist across these administrations––the ambition to diversify Iran’s foreign relations and economic motivations as the driving force behind those diplomatic maneuvers.

However, the policies pursued by Ahmadinejad, Rouhani, and Raisi also present notable differences in their conceptual underpinnings, geographical scope, institutional arrangements, and the external and internal factors that propelled them.

The trajectory of Iran’s “Look East” strategy, over the past two decades, and especially the way it is pursued under Raisi—“Look East” as the ultimate alternative, and not a complement, to Iran’s relations with the West—indicate a notable departure from the enduring principle of “neither East nor West.”1 The principle, once a fundamental tenet of Iran’s constitution and foreign policy following the revolution, seems to have relinquished its significance in the contemporary geopolitical climate of renewed great power competition and what is generally perceived as the rise of the East. Instead, Iran is now making concerted efforts to establish stronger partnerships, or even alliances, with Eastern powers. Although this shift has borne some fruitful outcomes, it has concurrently limited Iran’s foreign policy options, thereby constricting its diplomatic agility. This is compounded by a consistently cautious stance toward the West, particularly toward the United States, from Iran’s Eastern partners, including China and other Asian powers like India.

This issue brief begins by examining the historical background and development of Iran’s “Look East” strategy. It subsequently delves into a comprehensive analysis of how the strategy was implemented under Ahmadinejad, Rouhani, and Raisi. The brief then concludes by evaluating the implications for Iran’s foreign and domestic politics, as well as providing insights into future prospects.

The Origins and Evolution of Iran’s “Look East” Strategy

In the early 1990s, the Islamic Republic under President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani was confronted with the dual challenge of international isolation and economic hardship. The devastating consequences of the eight years of war with Iraq made economic reconstruction a top priority.2 However, strained relations with the West barred Iran from sourcing Western investments for its economic activities. In the face of these hurdles, Iran saw opportunities in the collapse of the Soviet Union, looking towards cooperating with the newly-independent neighboring republics.3 Additionally, Iran began to pursue stronger ties with Asian countries, following a developmental model in hopes of transforming itself into an “Islamic Japan.”4 This approach aimed at expanding Iran’s diplomatic and economic frontiers towards Eastern countries that were perceived as potential markets for Iranian oil and gas exports and potential sources of investment and technology transfer.

However, during the 1990s, Iran’s eastward orientation was not yet a robust strategy but rather a tactical response to internal and external pressures. The policy’s effectiveness was curtailed by factors such as ideological differences, Western influence on Asian countries, and regional rivalries. For instance, concerns regarding Iran’s aspirations to export its revolutionary ideals and the growing influence of formidable rivals, such as Türkiye, constituted significant obstacles that impeded Tehran’s ability to effectively protect its interests in Central Asia.5

A pivotal moment for Iran’s “Look East” policy was Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s election in 2005. He embraced a powerful ideological vision for Iran’s foreign policy that merged Shiite apocalyptic perspectives with globalist anti-Western sentiments, adopting an exceptionally confrontational stance against the West. Isolation and sanctions from the West pushed Iran toward alternative partners in the East, with a focus on Russia and China. Simultaneously, Iran regarded African and Latin American countries6 as potential partners in its endeavor to counter Western pressure. Under Ahmadinejad, the “Look East” policy was predicated on aligning with the rising East, which, broadly defined, was a stance against the West.

Ahmadinejad’s tenure saw some successes, such as expanded trade with China, improved defense ties with Russia,7 and enhanced relations with other Asian and Eurasian nations. However, trust issues between Iran and its supposed Eastern partners, Western pressure, and regional competition continued to present significant challenges. For example, from 2006 to 2010, Moscow and Beijing, both permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), endorsed UNSC resolutions against Iran regarding its nuclear program.8 This stance effectively dashed Tehran’s aspirations for international support from Eastern powers.

Unlike Ahmadinejad, his successor Hassan Rouhani championed a balanced foreign policy approach, pursuing “constructive engagement” with both Eastern and Western nations.9 This new approach led to the historic nuclear deal with the P5+1 group (the five permanent members of the UNSC and Germany) in 2015, providing respite from Western sanctions and breathing new life into dialogue with the West. At the same time, Rouhani remained steadfast in his commitment to the “Look East” policy, recalibrating it to align with his comprehensive foreign policy objectives. Under his tenure, Iran’s relationships with China and Russia significantly improved. This fact was underscored by the increasing number of high-ranking state visits and agreements inked between Tehran, Moscow, and Beijing.10

Rouhani’s foreign policy, however, faced substantial obstacles due to the withdrawal of the United States from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018. This development, compounded by the inability of other JCPOA signatories, including Russia and China, to provide Iran with effective alternatives to circumvent the reimposed sanctions, complicated Iran’s foreign policy landscape. Caught between these external pressures and the escalating domestic sabotage from hardliners11—those who firmly support the supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his anti-Western and conservative views—Rouhani did not have enough time to effectively recalibrate his foreign policy strategy.

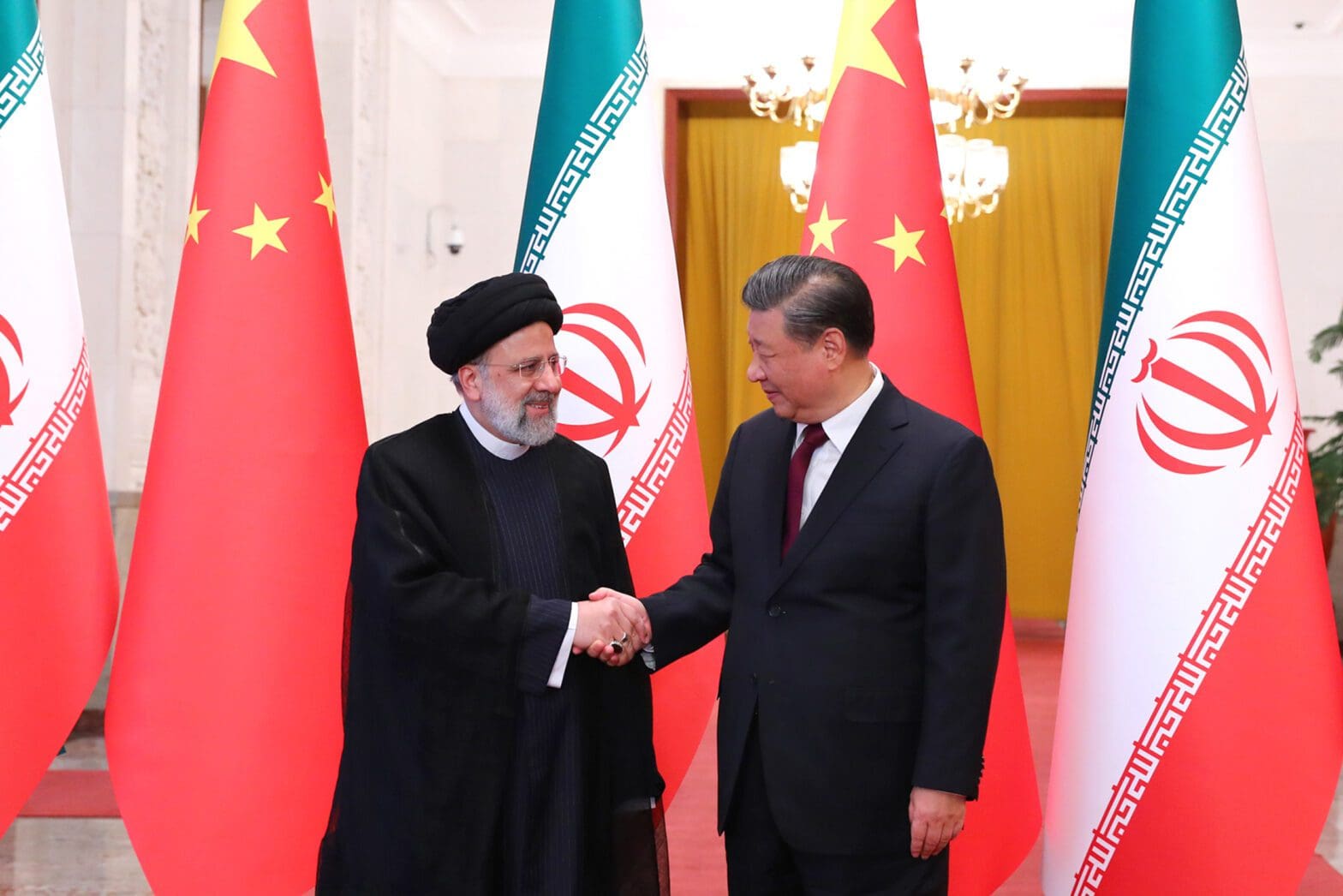

In 2021, Ebrahim Raisi’s election heralded a new phase in Iran’s “Look East” strategy. Raisi has adopted a more conservative and hardline approach to the West while prioritizing relations with the East. His policy is premised on the belief that Eastern countries, particularly China and Russia, are more reliable partners for Iran than the West. Raisi’s administration managed to make progress by implementing a 25-year strategic partnership agreement with China, gaining full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and expanding trade with Russia.12 Russia’s war in Ukraine, coupled with the escalating global rivalry between the United States and China, has reinforced Iran’s perception of the “West’s decline.”13 Consequently, Iran has placed greater faith in its economic and geopolitical prospects through partnerships with Moscow, Beijing, and other non-Western powers. This strategic calculation has fueled Tehran’s growing defiance and assertiveness in the pursuit of its “Look East” strategy. For Raisi and his administration, the “Look East” strategy holds the potential to not only counter the impact of American sanctions on Iran but also expand Iran’s range of strategic options in the long run.

Consistent Strategy, Diverse Attributes

In light of the foregoing, it can be contended that presidents Ahmadinejad, Rouhani, and Raisi each pursued the “Look East” policy with shared aspirations of diversifying Iran’s international relations and enhancing its economic interests. However, their execution of the policy varied, demonstrating distinct conceptual foundations, geographical priorities, institutional dimensions, and both external and internal driving factors.

Conceptual Foundations

The conceptual foundation of Iran’s “Look East” policy refers to the core reasoning and rationale for the country’s eastward orientation. Under Ahmadinejad, the “Look East” policy was seen as a tool for breaking diplomatic isolation and resisting Western pressure. The policy was rooted in an anti-imperialist worldview that positioned the West as an enemy and a threat not only to Iran but to all “oppressed nations” that were striving to preserve their sovereignty.14 He aimed to counter this threat by fostering connections with the East, specifically China and Russia, and other non-aligned or anti-Western nations such as Venezuela, Cuba, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Sudan, Zimbabwe, and North Korea. The goal was to establish a bloc of “resistance” nations that would challenge Western hegemony.15

Rouhani, taking a more balanced approach, saw the “Look East” policy not as a substitute but as a complement to relations with the West. His pragmatic outlook deemed the West a partner for Iran’s development and global integration rather than an adversary. He aimed to mitigate Iran’s nuclear dispute by securing the JCPOA, hoping to lift sanctions and enable cooperation. This viewpoint, shaped heavily by his foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, posited that tension-free relations with the West were a prerequisite for improved relations with the East, as it would amplify Iran’s bargaining leverage.16 The “Look East” policy, under Rouhani, was calibrated to his broader agenda of constructive global engagement.

Under Raisi, the “Look East” policy manifests as a strategic response to a perceived global “power transition,” with the West in decline and the East on the rise.17 The hardline faction to which Raisi belongs positions Iran as aligning with rising Eastern powers, elevating “Look East” from a tactical maneuver to a strategic choice. Deep-seated mistrust and pessimism towards the West, further entrenched by the failed nuclear deal, reinforce this eastward shift. While resembling aspects of Ahmadinejad’s policy, Raisi’s “Look East” distinguishes itself through its foundation in geopolitical understanding rather than ideology, signaling a more pragmatic, albeit equally anti-Western, orientation.

Geographical Scope

The geographical scope of the “Look East” strategy varies among Ahmadinejad, Rouhani, and Raisi, manifesting the diverse range of countries they consider as potential partners in their foreign policy. Ahmadinejad extended the “Look East” policy beyond Asia and Eurasia to Latin America and Africa.18 His focus was on fostering close ties with all countries that aligned with his anti-Western stance or confronted similar Western pressures. Simultaneously, he strived to enhance Iran’s presence in Africa through increased trade, investment, aid, and cultural ties.19

Rouhani effectively broadened the geographical scope of the “Look East” strategy to incorporate Eurasian powers. His policy aimed to foster balanced relations with key Eurasian actors, including China, Russia, India, and the European Union, viewing them as pivotal blocs within a broadly defined Eurasian landscape.20 The “Look East” strategy under Rouhani prioritized strengthening crucial bilateral ties with these powers, which also formed the core of regional and international initiatives. In his strategy, Rouhani included participation in initiatives such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).21 These multilateral engagements were seen as a complement to strengthened bilateral relations, together constituting his broadened “Look East” policy.

Raisi’s “Look East” policy strategically centers around Asia, giving due weight to Iran’s immediate neighborhood and also exploring connections further afield. This focus is reflected in two official concepts often mentioned by Raisi’s administration: the “neighborhood policy” and the “Asian policy.”22 Pursuing this strategy, the administration has achieved a normalization of relations with Saudi Arabia, sought better ties with other neighbors, and endeavored to enhance relations with nations as distant as Indonesia.23 While there has been outreach to Latin American countries as well, a focus on Asia undeniably remains the cornerstone of Raisi’s foreign policy approach.

Institutional Aspects

On an institutional level, the “Look East” policy signifies Iran’s degree and mode of engagement in regional and international initiatives led by or inclusive of Eastern nations. Each of the three presidents exhibited different institutional dimensions to their respective “Look East” strategies.

Ahmadinejad’s “Look East” policy primarily hinged on bilateral relations, particularly with China and Russia, while his multilateral engagement was limited. His ambitions to join the SCO were stifled by the unwillingness of member nations to become embroiled in Iran’s disputes with the West that had been exacerbated by the overly ideological tenor of Ahmadinejad’s foreign policy.24 Similarly, attempts to invigorate the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) and leverage platforms like the Organization of Islamic Cooperation as a support base for his anti-Western stance proved unsuccessful, further hampering his “Look East” strategy.25

Rouhani’s policy was a blend of bilateral and multilateral relations, yielding some success at multilateralism.26 His approach extended beyond bilateral ties, promoting engagement within multilateral frameworks involving Eastern countries. Successful instances of this include Iran’s integration into initiatives such as the China-led AIIB and BRI. Rouhani also made strides in Iran’s association with other organizations including the EAEU.

Raisi’s “Look East” policy has embodied a robust multilateral element, which has been partly successful. Raisi has underscored Iran’s active involvement in Eastern-led initiatives and organizations––a strategy yielding some significant outcomes. Notably, under his administration, Iran transitioned from an observer to a full member of the SCO after a 14-year period.27 He has also articulated Iran’s serious intent to amplify its cooperation with the EAEU and implement its comprehensive strategic partnership agreement with China. Moreover, he has expressed eagerness to join the Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa (BRICS) group.28 This emphasis on multilateral engagement, from SCO and EAEU to BRICS, signifies a substantial shift in the institutional approach to Iran’s “Look East” policy under Raisi.

External Drivers

The driving forces behind the “Look East” policy of each Iranian president have been shaped by distinct external circumstances. The impetus behind Ahmadinejad’s “Look East” policy was shaped by the crisis over Iran’s nuclear program, Tehran’s controversial role in the region, and Ahmadinejad’s explicit call for the annihilation of Israel.29 This trio of contentious issues fueled significant diplomatic isolation and intensified Western pressures and sanctions. Ahmadinejad endeavored to mitigate this isolation by turning to the East; he hoped to use those connections as alternative sources of support and cooperation. However, as mentioned previously, those hopes were largely unfulfilled, with Iran ultimately facing six UNSC resolutions endorsed by Russia and China, which were Tehran’s supposed allies.30

Rouhani’s “Look East” policy was primarily driven by the dynamics surrounding the JCPOA. Initially, his policy was motivated by the prospect of leveraging the nuclear deal to attract increased cooperation from countries like China and Russia. Subsequently, after the withdrawal of the United States from the JCPOA, the policy evolved to focus on preserving the remaining components of the deal. He also sought to exploit his connections with non-Western powers to reap economic gains stemming from the partial lifting of sanctions under the JCPOA and then to preserve some level of trade and investment flow when the United States reimposed sanctions on Iran under the so-called “maximum pressure” campaign.31

Raisi’s “Look East” policy, on the other hand, has been influenced by a variety of factors. The failure to revive the JCPOA and enduring U.S. sanctions have necessitated an alternative approach. At the same time, the shifting geopolitical landscape in Eurasia and the Middle East, exemplified by events such as the war in Ukraine and China’s growing role in the Middle East, offer new opportunities. Raisi seeks to leverage his ties with Eastern countries to amplify Iran’s strategic advantage. Additionally, Iranian officials hope that these ties can provide strategic resources and capabilities necessary for Iran’s economic development, or at least “resilience.”32

Domestic Drivers

Each president’s approach to the “Look East” policy has been shaped by domestic motivations that were intertwined with their own ideological perspectives, political affiliations, and societal segments they primarily represented.

Ahmadinejad’s “Look East” policy was powered by his ideological kinship and populist charm among certain factions of Iran’s political elite and society, most notably the hardliners and lower socio-economic classes.33 He tried to position himself as a defender of Iranian sovereignty against Western pressure, using his connections with Eastern nations as a symbol of national pride and dignity.34

Rouhani’s “Look East” policy was propelled by pragmatic necessities and moderate support within Iran, particularly from reformists and the middle classes. While acknowledging the reality and importance of Iran’s relations with the West, Rouhani also recognized the intrinsic value of robust relations with Eastern countries. His foreign policy resonated with his followers, who saw potential opportunities and benefits for Iran in fostering ties with both the West and the East.35

Raisi’s “Look East” policy is currently fueled by an increasing wave of authoritarian consolidation that has swept across Iran’s political landscape since the 2021 presidential election, particularly resonating with the conservatives and security forces. The rise in authoritarianism has prompted a tilt towards forming relationships with similarly governed countries like Russia and China.36 The widespread disqualification of nearly all moderate and reformist candidates by the Guardian Council in the 2021 election,37 along with the suppression of protests and dissent, including crackdowns on journalists, activists, and civil society organizations,38 all point to a clear consolidation of authoritarian power. Furthermore, the escalating influence of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in domestic affairs has led to the dominance of a military-centric security approach in foreign policy, warranting a close alliance particularly with Russia.39 The Raisi administration has witnessed a significant presence of former IRGC commanders in high-ranking positions, as well as in provincial and local authorities, and within the parliament. Moreover, the IRGC’s elite Quds Force has played an increasingly prominent role in shaping and executing foreign policy, particularly in the regional context, over the past years. Raisi’s foreign policy aligns tightly with the Supreme Leader and the preferences and interests of his loyalists, leaning on connections with Eastern powers as a stabilizing force amidst ongoing Western pressures.

From Non-Alignment to Strategic Realignment: Implication of Iran’s “Look East” Strategy

Iran’s “Look East” policy has taken different forms under the presidencies of Ahmadinejad, Rouhani, and now Raisi. The policy’s evolution has been marked by a strategic realignment, moving from an attempt to offset Iran’s international isolation under Ahmadinejad to a pragmatic balancing act under Rouhani, and finally to a more deliberate and concentrated consolidation under Raisi. Today, the Raisi administration’s actions are signaling a paradigm shift in Iranian foreign policy, where the principle of “neither East nor West,” a keystone of Iran’s foreign policy since the 1979 revolution, is less relevant.

The principle of “neither East nor West” was intended to maintain Iran’s strategic independence and non-alignment, a testament to the country’s quest for sovereignty in the face of global power dynamics.40 However, the current version of the “Look East” policy seems to contradict this principle. The policy under Raisi’s administration appears more akin to a bloc formation endeavor, strategically aligning with Eastern powers like China and Russia. This is a marked shift from the long-standing pillars of Iran’s foreign policy and underscores a strategic recalibration.

While the “Look East” policy has yielded certain benefits for Iran, such as increased resilience against Western sanctions and enhanced strategic leverage in global politics, it also runs the risk of significantly narrowing Iran’s foreign policy options. For instance, Saudi Arabia, Iran’s regional rival, has managed to maintain a balance in its relationships with both the East and the West, navigating the complexities of the geopolitical landscape more efficiently.41 By contrast, Iran’s increasing orientation toward the East may serve to further isolate it from the rest of the world, diminishing its diplomatic maneuvering space and exacerbating its geopolitical marginalization.

Independent observers and politicians in Iran consistently warn about the country’s growing dependence on China. Some even argue that without China’s leverage over the Islamic Republic, it would have been considerably more challenging for Tehran and Riyadh to achieve a successful agreement in normalizing their relations.42 While it is true that Iran has its own economic and security interests in seeking to normalize relations with Saudi Arabia, the substantial differences between the two nations would make it challenging for them to reconcile without active and dependable mediation from a major global power.

Despite Tehran’s 25-year comprehensive strategic agreement with Beijing, Iran’s neighbors across the Gulf have been more effective in attracting Chinese investments and avoiding geopolitical marginalization.43 This success can be attributed primarily to the policy of balancing and hedging pursued by the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states in the era of heightened great power rivalries.

It is crucial to note that Iran’s Eastern partners, including China, India, and, until recently even Russia, have traditionally adopted a cautious approach in their relations with Iran. While they show readiness to cooperate with Iran, they simultaneously tread carefully to avoid jeopardizing their ties with the West. This approach was evident before the JCPOA, when Russia and China adhered to international sanctions against Iran, highlighting their geopolitical and economic priorities.44 Therefore, the evolution of Iran’s “Look East” policy is inherently intertwined with the wider geopolitical interests of its Eastern partners.

This dynamic has been further complicated by recent global events, particularly the war in Ukraine. While the conflict has prompted Russia to be less mindful of its relations with the West, Moscow’s capacity to assist Iran, especially economically, has become more limited. Furthermore, other potential Eastern allies, such as India, place enormous value on their ties with the United States, thus moderating their engagement with Iran. China’s continued purchase of Iranian oil in recent years has provided some respite for Iran. However, the absence of alternatives in the market has compelled Iran to offer considerable discounts to Beijing, further limiting the economic benefits of this partnership.45 Consequently, while the “Look East” policy is a strategic move for Iran, the constraints imposed by the broader geopolitical landscape and the limitations of its Eastern partners underline the complexity of this approach.

At the domestic level, the “Look East” policy seems to be reinforcing the trend of increasing authoritarianism in Iran’s political system. The growing influence of the IRGC in foreign policy formulation, coupled with the military-security approach it champions, particularly the partnership with Russia, might further embed a security-oriented mindset in Iran’s external relations. This could have lasting implications for Iran’s domestic politics, potentially stifling political dissent, constraining political liberties, and contributing to a more centralized power structure. For instance, in recent years, the Iranian government has increasingly used Chinese technologies for tighter control over the internet and communication networks and, as a result, over its citizens.46 Also, in 2021, Iran signed an agreement with Russia to cooperate in the field of information security.47

Looking ahead, it is clear that the “Look East” policy, though offering a counterbalance to the relentless pressures and sanctions from the West, is far from a silver bullet solution to its array of foreign policy conundrums. Notably, genuine economic development and sustainable prosperity for Iran remain largely out of reach without a comprehensive resolution to its ongoing sanctions and the persisting tensions with Western powers. This is clearly manifested in Iran’s protracted economic problems, even in the face of heightened engagements and ties with Eastern powers. In essence, while pivoting to the East might offer some strategic benefits in the short-term, a well-rounded, carefully calibrated foreign policy strategy that bridges the East-West divide might be more instrumental in bolstering Iran’s global standing, its influence in the region, and its internal socio-political landscape.

Endnotes