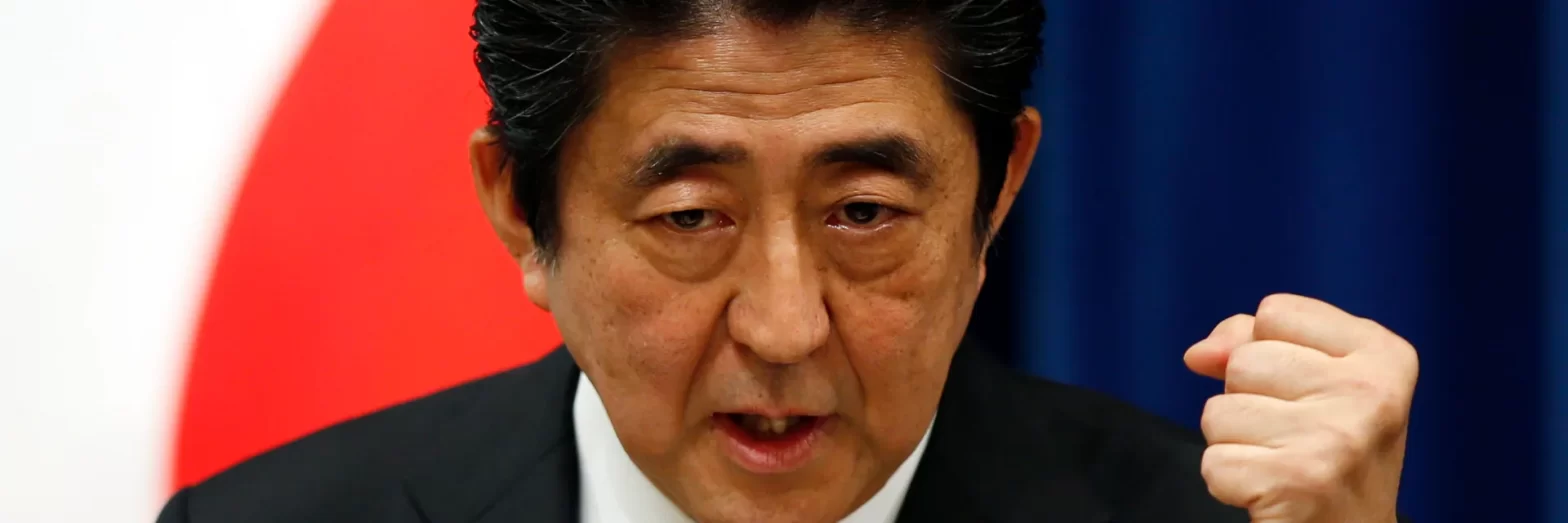

On July 1, 2014, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced long-anticipated measures that could result in the most important changes in Japanese national security strategy in more than six decades. Unveiled as a cabinet decision, the changes represent the biggest revisions in the country’s defense policy since adoption of the 1947 constitution prepared during the American occupation of Japan. Rather than propose constitutional revision, the Abe administration is advocating constitutional reinterpretation, for which the barriers to legislative approval are far less demanding. These steps presume an inherent right to collective self-defense, as permitted under the United Nations charter, though the cabinet document does not make explicit reference to this term. If implemented, the changes will extend Japanese security policy well beyond the constraints operative throughout Japan’s postwar history. Given that we have just marked the 69th anniversary of Japan’s unconditional surrender to the allied forces in World War II, it is a fitting time to examine what these policy changes could mean for Japan, the region, and the world.

The pronouncements represent the most recent efforts to redefine Japan’s contributions to international security following the end of the Cold War. Prime Minister Abe believes that current national defense policy limits Japan’s ability to protect its fundamental interests. The United States has welcomed these efforts, believing that Tokyo should assume a role more commensurate with its standing as a major power. By design, there is an inherent asymmetry in the U.S.-Japan security relationship. U.S. forces are unequivocally committed to the defense of Japan, without clarity in Japan’s precise contributions to U.S. strategy. This uneven alliance bargain was inherent in the security arrangements that the United States established decades ago. The question is whether these arrangements are sustainable for either Japan or the United States and the consequences for East Asia if they are not.

The cabinet announcement argues that growing threats to Japanese security necessitate these changes. The document states that “the international environment surrounding Japan has become increasingly severe.” It advocates more active measures to prevent conflict and deter possible threats to national security. The principal factors preoccupying Japanese defense planners are North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities and China’s increased military reach, especially Beijing’s maritime and air patrols near the Senkaku Islands (known to the Chinese as the Diaoyus), where China openly contests Japan’s claims to sovereignty. The cabinet document also draws attention to broader technological changes in warfare and to new risks such as cybersecurity, claiming that “any threats, irrespective of where they originate in the world, could have a direct influence on the security of Japan.”

The announced changes are fraught with implications that have yet to receive full scrutiny within Japan and have triggered very sharp responses from neighboring states, especially China and South Korea. Prime Minister Abe argues that extant policies do not permit sufficient integration with U.S. forces that are essential to addressing Japan’s security needs. But he also contends that Japan is not trying to modify Article IX of the constitution (widely known as the “no war” clause) and is not advocating direct involvement of Japanese forces in overseas combat missions.

However, neither China nor South Korea seems assured by these statements. The principal objections raised by both countries are rooted in history, contending that Abe remains unreconciled to the outcome of World War II and unprepared to admit fully to Japan’s conduct during the conflict. The prime minister’s December 2013 visit to the Yasukuni Shrine, where the souls of Japan’s war dead (including 14 wartime leaders convicted of Class-A war crimes at the Tokyo tribunals) are interred, provoked intense reactions from both capitals. The Abe administration’s equivocal reaffirmation of earlier Japanese declarations of regret over its wartime behavior and acknowledgment of the Imperial Army’s role in organizing forced prostitution for its troops caused additional damage. For these reasons alone, China and South Korea voice grave suspicions about the prime minister’s intentions.

Abe believes the policy changes validate his deeply held convictions about national sovereignty. In his view, Japan has long been hobbled by the constraints imposed under the U.S. constitution. His views are historical, personal, and strategic. Abe’s grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, played a major role in Japanese decision making throughout WWII and served as prime minister during the late 1950s and again in 1960. Kishi, who was jailed but never indicted by the United States after Japan’s surrender, subsequently became a severe critic of “victor’s justice.” He openly objected to the constraints imposed under Article IX and sought without success to revise the constitution.

Abe sees himself as his grandfather’s legatee, but he is also realistic about domestic political circumstances. Support for the constitution remains very strong in Japan, and only small portions of the population deem constitutional change an important policy priority. Abe’s critics describe his strategy as “revision by stealth,” altering policy parameters in a series of incremental steps. This is not a new objective for Abe. During his previous tenure as prime minister in 2006-07, he established an advisory panel to study the right to collective self-defense, but the panel did not complete its report until nearly a year after his resignation. When Abe resumed leadership in December 2012, he quickly reestablished the advisory group, but delayed release of the report until there was concurrence with various measures by New Komeito, his junior partner in the ruling coalition.

In his earliest months in his second stint as prime minister, Abe focused predominantly on Japan’s economic revival, and his approval ratings exceeded the 70 percent level. Recent polls place his public support levels in the mid to upper 40 percent range. In a poll by Yomiuri Shimbun taken shortly after release of the cabinet document, Abe’s support plummeted to 48 percent, a nine-point drop from the newspaper’s findings from the previous month. Other polls show even lower levels of support.

Abe has demonstrated an unwavering commitment to major security priorities throughout his second tenure as prime minister. In December 2013, Japan released its first national security strategy, including a new National Defense Program Guideline and recommendations for the Mid-Term Defense Program. These include a three percent defense budget increase in 2013 (there have been additional increases in 2014), the first appreciable enhancements in the defense budget in well over a decade. The increases favor air, naval, and missile defense forces and the creation of new amphibious capabilities. The new Defense White Paper, released in August 2014, intimates that additional increases will be required in future years. Abe has also created a national security council modeled on the U.S. body and passed a state secrets law that does not include provisions for legislative oversight.

Abe has thus put forward ambitious policy goals. According to the cabinet document, Japan will heighten assistance for U.S. forces undertaking actions in defense of Japan; will provide logistical support “for the armed forces of foreign countries engaged in activities for ensuring Japanese security or for peace and security of the international community;” will be permitted to carry weaponry to protect Japanese peacekeepers; will be able to rescue Japanese nationals abroad (if permitted by the country where the nationals are located); and, perhaps most consequentially, will respond to “armed attack against a foreign country that is in a close relationship with Japan…and as a result threatens Japan’s survival.” But the imprecision in these announced goals and the lack of specificity in how they might be translated into operational policy remain disquieting.

Prime Minister Abe insists that these issues will be fully addressed in the fall session of the lower house of the Diet (the Japanese legislature). They will then be linked to pending revisions in the U.S.-Japan Defense Cooperation Guidelines, scheduled for release in December 2014. A wide array of new or revised laws must be presented for review and approval by the Diet, and Abe has pledged that pending legislation will be “seamless” in ensuring in Japan’s security. But ample skepticism is warranted about his assurances. Abe has painted future defense requirements with a very broad brush, and there are major ambiguities and differences in interpretation on how policy changes might apply in potential contingencies. Other critics question whether changes are even needed to justify the right of self-defense in relation to North Korea and China. Japan has entered uncharted waters, without undertaking full deliberation over policy changes of such magnitude.

The prime minister argues that global and regional security has entered a far more worrisome phase and that Japan must possess new policies and new capabilities to address these risks. But what larger ends would Japan’s policy initiatives serve, and do these goals enjoy genuine support within the Japanese body politic? Does the public grasp the potential consequences of these policies? Would they permit meaningful enhancement of the U.S.-Japan alliance, or would they contribute to a more contentious, less predictable bilateral relationship? Would these changes be deemed acceptable by Japan’s neighbors? All these questions warrant close, careful, and open deliberation, beginning first with the citizens of Japan, whose well-being such constitutional reinterpretation is intended to protect.

This post originally appeared on

Lawfare

.