The Yemeni people have reason to celebrate. They managed to keep their 12-month uprising largely peaceful, held successful and transparent presidential elections and ultimately put an end to the country’s autocracy. Though it is still too early to judge the success of the post-Saleh government, it seems the Yemeni model of transition is laying the groundwork for a more democratic Yemen.

The GCC initiative that outlined the transfer of power from former President Ali Abdullah Saleh to an elected president may not have satisfied everyone in the Yemeni uprising. There was, after all, only one candidate in the running. But it has certainly created a politically viable alternative to Mr. Saleh’s autocracy and ended a brutal stalemate that impeded any genuine political change for almost a year.

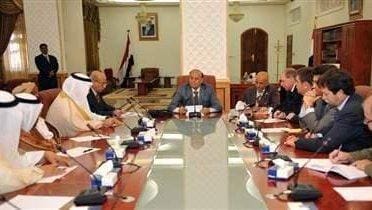

Since the signing of the GCC initiative, a unity government has been established, in addition to a military and security reform committee. With the success of the recent presidential elections, Abdurabu Hadi now serves as executive. Remarkably, all of this progress has been made in only a few months – despite the fragile security environment in Yemen – suggesting that similarly impressive political changes could be forthcoming.

When it was first launched, the GCC plan was supported by the Gulf countries and broadly by the international community. Last month’s successful presidential election demonstrated that the majority of the Yemeni people have also bought into the new political process, lending the initiative local credibility.

The successful presidential election shows unmistakable progress toward democracy. This is very important as Yemenis now are seeing a possible end to one year of uncertainty and instability. The political process has earned the support of the international community, Gulf countries and most importantly the Yemeni people. The impressive 60 per cent participation in the election demonstrates a trust in the political process, granting the newly elected leader popular legitimacy and power that he needs to make change.

The success of this model of negotiated regime change and a coordinated transition is important not only for the Yemeni people but also for the entire region, particularly those countries experiencing popular unrest. Yemen has thus far been the only Arab country to negotiate the exit of its leader. With Bashar Al Assad still clinging to power, Yemen’s model of coordinated transition may well provide insights for Syria, where the international community remains divided in its approach to the increasingly violent crisis.

While they enjoy a well deserved celebration after the successful election, Yemenis should keep in mind that the hard work of rebuilding the country has just begun.

Enormous challenges lie ahead, and many unanswered questions. Just this week, Mr Saleh made a new condition for his departure: he won’t go unless 10 of his political and military rivals leave too. This was widely seen as a ploy for the ousted leader to remain in Yemen longer.

There are also other lingering issues. The southern secessionist movement, the Houthis, Al Qaeda and the severe lack of economic development are only examples of the coming challenges. Mismanagement of the rebuilding process could easily unravel the progress that has already been made.

The first step towards a genuine rebuilding of the country should involve an inclusive national reconciliation process beginning with a national dialogue. The coordinated transitional model left the domestic power struggle over the country’s army and large bureaucratic system intact, and the new Yemeni leadership must now unite these forces behind transition. In so doing, this leadership should realise that transitioning to a strong democratic model that treats diversity in Yemeni society as an opportunity rather than a threat is a key factor in success.

The grievances of southerners in particular should be recognised and addressed through the democratic system. The southerners – as stakeholders contributing equally to the rebuilding process – should realise that they will need to give this model a chance. Since 1994, they have suffered from Mr Saleh’s autocracy that marginalised the southern region in particular. Today, however, the southerners will finally have the opportunity to air their grievances with the national government and contribute equally to building a democratic system.

To ensure success, Yemen’s coordinated transition should lead to the construction of highly transparent state institutions. Again, the model of negotiated exit has provided a new leader and his staff but not state institutions. Reforming the public sector institutions and eradicating corruption must begin immediately. Otherwise, this model will prove to be one of presidential change rather than genuine regime change.

Finally, we must not overlook that this is a historical moment for Yemenis to begin a new era of rebuilding and reconciliation. Though presidential elections were critical to the rebuilding process, Yemenis should know that this is not enough. A new executive cannot reform the entire system alone. All stakeholders are equally responsible for both success and failure.

The coordinated transition model has provided an opportunity, yet the model will not be fully successful without a genuine and inclusive reconciliation process. With elections and free choice comes a responsibility – to replace protests with dialogue as the most effective way forward for the country.