The United States of America and Eastern Mediterranean Security

March 2025

Introduction

The Mediterranean has often been a contested space, affected by the demise of the Ottoman Empire and the end of European empires in North Africa after the Second World War.1 U.S. interests in the Middle East have fluctuated over time, constituting relatively modest objectives: maintaining energy supplies; countering the spread of weapons of mass destruction, counterterrorism and intelligence cooperation, support for key allies such as Israel—including Camp David compliance; and competing with other great powers. The U.S. had also supported the two-state solution over a period of decades, however President Trump’s pick for the role of U.S. ambassador to Israel, Mike Huckabee, has previously endorsed a “one-state solution.”2

Since Washington’s 2017 strategic reorientation towards Russia and China, the war in Ukraine and competition with China have taken on a greater significance in U.S. foreign policy than Eastern Mediterranean security. That was the case until the war in Gaza began on October 7, 2023. The Biden administration has continued to work closely with Prime Minister Netanyahu’s coalition government during Israel’s military campaigns in Gaza, Lebanon, and beyond, especially in providing additional U.S. military deployments to the region.3 The Gaza war has fundamentally undermined the Abraham Accords, which rested on further Arab state normalization with Israel. However, a multitude of other trends and issues have impinged on energy projects in the region. For example, the U.S. revoked its initial support for the EastMed pipeline project—transporting gas from Egypt and Israel to Cyprus and Greece and onto the rest of Europe—for economic and commercial reasons (as the pipeline bypasses Türkiye and therefore adds to geostrategic tensions) and for environmental concerns, with green energy projects now being preferred.4 There may still be potential in the Eastern Mediterranean Energy Forum, since it could lead to cooperation on a wider range of energies, but again, this hinges on resolving the war in Gaza.5

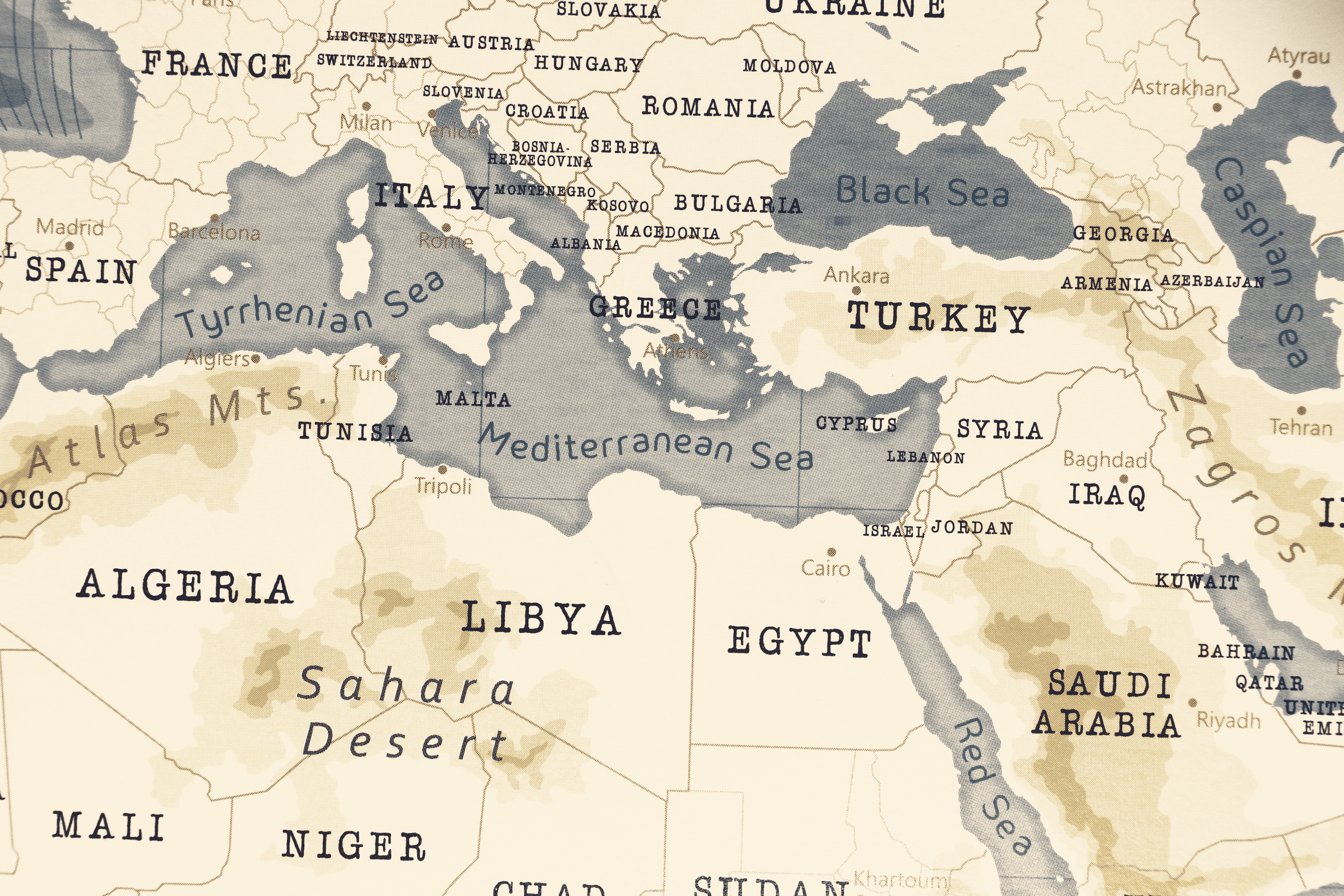

This chapter focuses mainly on contemporary U.S. engagement in the Eastern Mediterranean—comprised of Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, Israel, the Palestinian Territories, Lebanon, Libya, Syria, and Türkiye—where conflict and state fragmentation have facilitated some efforts at de-escalation as well as local invitations or support for alternative external power engagement, including from Russia and China.

Funding and Assistance

U.S. bilateral assistance has tended to concentrate on just two regional states: Israel and Egypt. Between 1946 and 2023, U.S. economic and military aid to Israel amounted to about $300 billion,6 while U.S. aid to Egypt, in second place, amounted to more than $150 billion.7 In 1981, one of the first USAID-managed programs in the region was Middle East Regional Cooperation (MERC), conceived to encourage scientific cooperation between Egypt and Israel. The Middle East Multilaterals (MEM), part of the Economic Support Fund and the U.S. Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, focused on building technical cooperation between Arabs and Israelis. MEM continues to support the Middle East Desalination Research Center (MEDRC) in Oman. Founded in 1996, MEDRC is seen by the U.S. as a part of the Middle East peace process as it includes Israelis. The U.S. contribution is marginal, typically amounting to less than $1 million per year.8 The U.S. is also an observer of the Synchroton-light Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East (SESAME) which opened in Jordan in 2017.9 The Middle East Partnership for Peace (MEPPA) was set up as two concurrent programs in 2021: one USAID program to support Israeli-Palestinian reconciliation, and another, a U.S. international development corporation to strengthen the Palestinian financial sector. The $250 million allocated for 2021-2025 is increasingly being spent on the USAID track.10

U.S. policy in the Middle East experienced a step change following 9/11 terror attacks. Washington’s neo-conservative elite led a militarized response in the form of the Global War on Terror (GWOT), centering first on Afghanistan (2001) and then Iraq (2003). In contrast to the many smaller State Department and USAID programs, GWOT cost an estimated $9 trillion dollars,11 a deficit that has arguably reshaped the domestic U.S. political landscape and limited U.S. ambitions abroad, enabling other actors to fill the vacuum.

One of the larger programs aimed at civil society and democratic reform, the Middle East Partnerships Initiative (MEPI), launched in 2002, had modest impacts after 20 years and $1 billion spent.12 Furthermore, President Trump’s 2020 proclamation recognizing Morocco’s sovereignty over the entire Western Sahara surpassed MEPI support for Western Saharan civil society capacity building—a move that followed Morocco’s normalization with Israel through the Abraham Accords.13 Middle East Regional (MER) is another USAID-managed project designed to support action on climate change, water and food security, state fragility, democracy and governance, and inclusive economic growth. MER’s budget in 2024 was just $8 million, intended to complement rather than replace foreign bilateral assistance.14

U.S. Policy, Threats and Challenges

Despite many in the region having become receiving, transit, and (increasingly) sending states for refugees and migrants—escaping war zones, extreme poverty, and state collapse—there has been no holistic U.S. strategy in response.15 Moreover, there has been a recurrent theme of lost credibility —President Obama’s ‘leading from behind’ on Libya in 2011,16 or inaction following Bashar Assad crossing a ‘red line’ by using chemical weapons in Syria in 2015.17 This emboldened Russia, whose support and involvement secured Assad’s patronage alongside military support from Hezbollah and the Iranian Quds Force. President Assad’s attempts to generate revenues put Syria at the heart of the regional Captagon trade. This fact, along with attempts to address reconstruction and the return of refugees to Syria, perversely encouraged many regional states and the Arab League—initially breaking off diplomatic relations—only to reinstate them. Assad’s overthrow in early December 2024 simply adds more uncertainty to U.S. policy and the regional environment going into the first year of the second Trump presidency.

The Arab Gulf States have continued to secure for themselves a key role in the Mediterranean in recent years, first through the Arab Peace Initiative, which set the conditions for normalization with Israel in 2002. Neither Israel nor the U.S., during the Second Intifada and the GWOT, were ready or willing to incorporate this approach into their own respective policies. This was largely for domestic political reasons. Qatar, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait have continued to play key roles in the political economy of various North African and Levantine states, up to and post-Arab Spring. Their investments have been especially important to Egypt’s economic stability, along with UAE mediation over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). The Emirates has also developed close relations with Cyprus and Greece. The U.S. and India are both involved in the I2U2 Group with Israel and the UAE, and through the India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC)—designed to shift focus away from China and progressively integrate the Indo-Pacific with Europe through the Arabian Peninsula. These efforts have so far been undermined by the war in Gaza.

France is also playing a greater role in Gulf affairs, which may lead to more joint initiatives in the Levant, where it has had historic, but now waning, influence. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman briefly detained Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri in Riyadh in 2017 in protest of Hezbollah’s role in Lebanese politics.18 It was French President Macron, not President Trump, who helped secure his release.

U.S. foreign policy often hinges on the U.S. president’s political will to act. Where President Trump did act, his “scorched earth” and limited initiatives towards the Palestinians, such as ‘Peace to Prosperity: A Vision to Improve the Lives of the Palestinian and Israel People,’ have been roundly rejected by the Palestinian leadership for their bias in favor of Israel.19 Amid further conflict and absent a viable peace process, pressures associated with the U.S.-led Abraham Accords are creating a series of domestic and regional tensions.20

Into Biden’s administration in 2021 and policy impact in the Middle East was deliberately limited. The result of a lack of U.S. pressure more broadly can be attributed to outcomes such as disintegration in Libya, democratic backsliding in Tunisia since July 2021, and growing political instability in the Sahel as both the U.S. and EU focused on limited terrorism and migration concerns. Diplomacy with Iran was slow, and absent snapback into the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), Iran has been relatively free to continue to develop its nuclear, missile and drone programs. Although there were some U.S. negotiations with Saudi diplomats on the establishment of a Palestinian state, that effort appears to have peaked on October 6, 2023.21 The U.S. Secretary of State, Anthony Blinken, has spent many months since then attempting to prevent escalation during the Gaza war. Still, his efforts have ultimately failed, and Israeli strikes have continued against targets in Syria, Iran and Lebanon.

U.S. engagement with local partners, such as Türkiye and Egypt, remains piecemeal and strained. There are U.S.-Türkiye tensions over the Kurdish community, policies towards Iran, hosting the Hamas leadership, and Turkish acquisition of Russian missiles and congressional holds an major new arms sales to Ankara. However, Türkiye is an important NATO member and remains vital to several policy briefs, even if U.S.-Türkiye relations remain rather transactional.22 U.S. relations with Cyprus have been much better, with both countries engaging in a strategic dialogue in 2024.23

In a complex security, energy, and terrorism environment. However, U.S. policy has focused on tactical military cooperation and external threats, rather than addressing domestic socioeconomic conditions in many countries. The MENA region has a history of poor infrastructure connectivity, compromised by political tensions and instability, which slows progress further. Energy projects with the Arab Gulf States have driven opportunities, such as the three-way deal between the UAE, Israel, and Jordan, until Jordan cancelled in protest of the Gaza war.24Beyond Gaza, the Cyprus issue, Greece-Türkiye maritime border delineation—although a détente has existed since May 2024 25—and the Libyan civil war will continue to have a bearing.26 The Egypt-Türkiye rapprochement goes some way to advancing cooperation on Libya, but it will take many years for the damage and chaos in Libya to be reversed.27

Meanwhile, China has stepped in with its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in a more meaningful way than the U.S. or IMEC (so far), advancing cooperation across retail, financing, and manufacturing. China is a major trading partner and a growing influence in many of the Gulf states. In addition, there is some analytical coverage of China’s prepositioning of dual-use material in ports where it has a presence.28 However, contrary to many western states, China’s arms sales and overall foreign policy impact is minimal.29 China is growing its regional diplomatic role: having helped broker the Saudi-Iran normalization deal in 2023; bringing representatives from Fatah and Hamas and others to Beijing in July 2024 during the Gaza war; and opposing Israel’s violation of Lebanese sovereignty.30 Since the onset of Israel’s war on Gaza, the United States has suffered from severe reputation damage in the Arab world and China is the prime beneficiary.31 Jordanians, Lebanese, and Mauritanians view China as a more prudent security actor than the U.S., and even in Kuwait—which relied on U.S. ousting Iraqi troops during the 1991 Gulf war—popular opinion is almost evenly split between the U.S. and China.32

Conclusion

Robust engagement throughout America’s unipolar moment in the 1990s could have yielded a socioeconomic renaissance along the southern shores of the Mediterranean before the Camp David summit in 2000 and long before the Arab Spring crystalized state fragility and prized regime survival. The GWOT clearly squandered U.S. leverage over adversaries such as Iran. Some of the trillions of dollars lost in the GWOT could have supported substantial healthcare, education and industrialization projects throughout the Global South, which when combined, could have generated unprecedented levels of economic development, integration, and good will. U.S. policy has been incredibly narrow, seeking to avoid regional spillover from the U.S./Israel and Iran’s so-called “Shadow War”—cyber and economic warfare, military strikes, and assassinations. Such an approach has evidently failed. Instead, adapting and better aligning international, inter-regional, and local interests to address the roots of a series of civil and regional conflicts might re-emphasize to many the value of Pax Americana.

Endnote

1 Ennio Di Nolfo, “The Cold War and the Transformation of the Mediterranean, 1960-1975,” in The Cambridge History of the Cold War, eds. Melvyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 238–257, https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521837200.013.

2 Adriana Gomez Licon and AP, “What Mike Huckabee, Trump’s Pick for Israel Ambassador, Has Said about the Middle East,” Time, November 13, 2024, http://archive.today/2024.11.14-200402/https://time.com/7176436/mike-huckabee-trump-israel-ambassador-palestinians-middle-east/.

3 Neri Zilber and Felicia Schwartz, “US Adds to Military Deployments to Protect Israel from Iran Retaliation,” Financial Times, 3 August 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/d6fd43b9-5e88-4de9-b000-16dcd2fbcf59.

4 Nektaria Stamouli, “EastMed: A Pipeline Project that Ran Afoul of Geopolitics and Green Policies,” Politico, January 18, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/eastmed-a-pipeline-project-that-ran-afoul-of-geopolitics-and-green-policies/.

5 Remarks by Geoffrey R. Pyatt, “Energy and Geopolitics in the Eastern Mediterranean,” Bureau of Energy Resources, U.S. Department of State, October 15, 2024, https://www.state.gov/energy-and-geopolitics-in-the-eastern-mediterranean/.

6 Jonathan Masters and Will Merrow, “U.S. Aid to Israel in Four Charts,” Council on Foreign Relations, November 13, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/article/us-aid-israel-four-charts.

7 Masters and Merrow, “U.S. Aid”.

8 Jeremy M. Sharp et al., “U.S. Foreign Assistance to the Middle East: Historical, Recent Trends, and the FY2024 Background Request,” Congressional Research Service Report, August 15, 2023, 11, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46344.

9 “What is SESAME?,” SESAME,, https://www.sesame.org.jo/about-us/what-is-sesame.

10 Sharp et al., “U.S. Foreign Assistance,” 11.

11 Jill Kimball, “Costs of the 20-Year War on Terror: $8 Trillion and 900,000 Deaths,” Brown University, September 1, 2021, https://www.brown.edu/news/2021-09-01/costsofwar.

12 Amy Hawthorne, “The Middle East Partnership Initiative: Questions Abound,” Sada, August 26, 2008, https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/2008/08/the-middle-east-partnership-initiative-questions-abound?lang=en.

13 Donald J. Trump, “Proclamation on Recognizing the Sovereignty of the Kingdom of Morocco over the Western Sahara,” The Trump White House Archives, December 10, 2020, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-recognizing-sovereignty-kingdom-morocco-western-sahara/.

14 Sharp et al., “U.S. Foreign Assistance,” 11.

15 Jon B. Alterman et al., Restoring the Eastern Mediterranean as a U.S. Strategic Anchor, (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 22, 2018), https://www.csis.org/analysis/restoring-eastern-mediterranean-us-strategic-anchor.

16 Michael Boyle, “Obama: Leading from Behind’ on Libya,” The Guardian, August 27, 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/cifamerica/2011/aug/27/obama-libya-leadership-nato.

17 Patrice Taddonio, “‘The President Blinked’: Why Obama Changed Course on the ‘Red Line’ in Syria,” PBS Frontline, May 25, 2015, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/the-president-blinked-why-obama-changed-course-on-the-red-line-in-syria/#:~:text=One%20year%20earlier,%20President%20Barack%20Obama%20had%20described.

18 “Saad Hariri: Saudis Detaining Lebanon PM Says Michel Aoun,” BBC News, November 15, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-41995939.

19 Round table with a senior U.S. diplomat, March 2, 2023.

20 Robert Mason, Guy Burton, and Banafsheh Keynoush, The Abraham Accords: National Security, Regional Order and Popular Representation (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2025).

21 Franklin Foer, “The War that Would Not End,” The Atlantic, September 25, 2024, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2024/09/israel-gaza-war-biden-netanyahu-peace-negotiations/679581/.

22 Rich Outzen and Can Kasapoglu, “US-Turkey Relations in an Era of Geopolitical Conflict,” The Defense Journal, no.3 (June 2024), https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/content-series/ac-turkey-defense-journal/us-turkey-relations-in-an-era-of-geopolitical-conflict/.

23 Menelaos Hadjicostis, “US, Cyprus Embark on Strategic Dialogue that Officials Say Demonstrates Closest-Eve Ties,” Associated Press, June 17, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/cyprus-us-strategic-dialogue-defense-energy-security-visa-waiver-0775383a479e70e8d5e5c5f4a2d4912a.

24 Bruce Riedel and Natan Sachs, “Israel, Jordan, and the UAE’s Energy Deal is Good News,” Brookings. November 23, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/israel-jordan-and-the-uaes-energy-deal-is-good-news/#:~:text=This%20week%20in%20Dubai,%20Israel,%20Jordan,%20and%20the; “Jordan Refuses to Sign Water, Energy Deal with Israel,” Arab News, November 17, 2023, https://www.arabnews.com/node/2410471/middle-east.

25 Sinem Cengiz, “Gulf States May Benefit From Turkish – Greek Détente,” Arab News, May 17, 2024, https://www.arabnews.com/node/2512271.

26 John Calabrese, “How the ‘New’ Eastern Mediterranean Can Serve as a Bridge between the Gulf and Europe,” Manara Magazine, June 18, 2024, https://manaramagazine.org/2024/06/how-the-new-eastern-mediterranean-can-serve-as-a-bridge-between-the-gulf-and-europe/.

27 Giorgio Cafiero, “Sisi’s Visit Solidifies a New Phase in Egypt and Turkey’s Ties,” New Arab, September 10, 2024, https://www.newarab.com/analysis/sisis-visit-solidifies-new-phase-egypt-and-turkeys-ties.

28 Zongyan Zoe Liu, “Tracking China’s Control of Overseas Ports,” Council on Foreign Relations, August 26, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/tracker/china-overseas-ports.

29 Robert Mason, “China and Regional Stability in the Middle East: Economics, Engagement and Great Power Competition,” in Routledge Companion to China and the Middle East and North Africa, ed. Yahia H. Zoubir (Abingdon: Routledge, 2023), 125–139, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003048404.

30 “China Says It Opposes Any Violation of Lebanon’s Sovereignty,” Reuters, September 29, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/china-says-it-opposes-any-violation-lebanons-sovereignty-2024-09-29/#:~:text=China%20opposes%20any%20violation%20of%20Lebanon%27s%20sovereignty%2C%20China%27s,airstrike%20on%20Beirut%20killed%20Hezbollah%20leader%20Hassan%20Nasrallah.

31 Michael Robbins, Amaney A. Jamal, and Mark Tessler, “America Is Losing the Arab World and China Is Reaping the Benefits,” Arab Barometer, June 11, 2024, https://www.arabbarometer.org/media-news/america-is-losing-the-arab-world-and-china-is-reaping-the-benefits/.

32 Robbins, Jamal, and Tessler, “America Is Losing the Arab World.”